Averaging about 17 miles a day, Finn and Tereza work their way up the Main River and reached Würzberg. They still have many more miles of the Main ahead of them before they reach the first canal along the route to Russia. Watch this video and see how our young travelers are getting into their groove.

Archives: Articles

IssueM Articles

To the Black Sea – Episode 4

Their destination, Sochi, Russia, was 1,500 miles away as the jet airliner flies, but Finn and Tereza are in no hurry and determined to travel in a manner that’s kind to the environment. They have been underway for a week now. Watch this video to see the beauty and adversity they discover in the first week of their journey, which lands them in the Bavarian city of Aschaffenburg, about 50 miles from their start at Mainz.

Watch Episode 4

To the Black Sea – Episode 3

With no car, Finn and Tereza have to figure out how to get their boat to Mainz, Germany. With all their supplies (and a guitar) aboard JILL, their 16’ Matinicus double ender, their goal was to get her in the water and spend their first night under the open sky. Watch this video to see how they fared!

Watch Episode 3

To the Black Sea – Episode 2

JILL, the boat Finn and Tereza have been building for their journey across Europe to Russia, is still not finished. Watch this video to see the challenges finishing JILL and the final stages of the pre-trip preparations.

Watch Episode 2

To the Black Sea – Episode 1

Students at Brockwood Park School in Hampshire, UK, Finn Cameron-Turner and Tereza Deminova, both 17, built a 16’ Matinicus double-ender. They had some help from a mentor and other students during the construction at the international school located in England’s Hampshire countryside, but it will be up to the two of them to row and sail the boat over 1,500 miles from Mainz, Germany, to Sochi, Russia, Tereza’s home town.

They’ll cross Europe on inland waterways, the last of which, the Danube, will deliver them to the Black Sea for the final leg along an exposed coast. For Finn and Tereza, the voyage is more than a summer vacation. They’ll continue their education by learning about navigation, sailing, and different languages and cultures. The state of the global environment is of great concern to them and they hope to demonstrate that travel, even for Tereza to get from school to her home in Sochi, can be done with a minimum of ecological impact. We’ll follow along on the adventure with regular installments of videos from Finn and Tereza. Watch this video to get to know the two adventurers.

Watch Episode 1

Hooper Bay

I recently parted with my Hooper Bay kayak, the only remaining relic of my first efforts as a boatbuilder 40 years ago. It was my second kayak, the first being one I designed after poring over my father’s copy of Adney and Chapelle’s The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America. That kayak was an awkward platypus of elements I’d seen in the book and turned out to be a bland dilution of whatever qualities the original kayaks might have possessed.

That kayak got me afloat, but I gained a new appreciation for the traditional forms I’d appropriated for it when I met David Zimmerly in 1978 at Port Townsend’s Wooden Boat Festival. He gave a talk there on the Hooper Bay kayak, which I recognized as the same style as the Nunivak Island kayak included in Skin Boats.

Nunivak is about 75 miles due south of Hooper Bay, and both are inhabited by the Yupik people of Alaska’s west coast. I was taken in by David’s detailed description of the Hooper Bay and the work of Yupik master kayak builder Dick Bunyan. David kindled my interest by giving me a photocopy of his draft of his then yet-to-be-published book, Hooper Bay Kayak Construction.

The Hooper Bay design was thoroughly and beautifully documented in David Zimmerly’s book, “Hooper Bay Kayak Construction.” The book is out of print now, but there are some old copies available from online used-book outlets.

It included detailed drawings of every piece, photographs of every step of the process from collecting driftwood to paddling the finished kayak. All that fall after the festival, I gathered driftwood, something I’d been doing since I was a youngster, helping my dad collect red cedar for fencing our yard. The beaches near home also had a bit of Alaska yellow cedar—straight stock for steam-bent frames and the coaming hoops; crooks for deckbeams the curved lower stempiece.

I learned a lot building the Hooper Bay: cutting straight and hooked scarf joints, half-lap joints, and mortises and tenons on compound bevels; working with crooks, carving stempieces, and steam-bending frames and coamings. Aside from the practical experience, I gained a better understanding of the sophistication of traditional designs and the centuries of experience and knowledge that went into them.

The Hooper Bay was meant for hunting seals in the Arctic and occasionally for ferrying people short distances across protected water, with as many as six aboard: two back-to-back in the cockpit, one on each deck, and one inside each end. It was only 15’ long, quite short compared to a modern touring kayak, but with a beam of 30”, a depth of 18” and weighing over 70 lbs, it was a big vessel. As deep as it was, the coaming came up to my armpits. I made a single-blade paddle of the type used for the Hooper Bay and paddled it like a canoe, alternating sides. It made for a slow, meandering course, so I never traveled far.

When it still had its canvas skin and was seaworthy, the Hooper Bay was a restful place to lie in with its decks for a cathedral ceiling and its cockpit opening for a skylight.

On summer days I would paddle a mile offshore, stow the paddle inside, and slide into the kayak and let the afternoon’s land breeze carry me back to the beach. Sometimes I’d take a book and read. Twice I took a cassette recorder and made spoken letters for my great aunt in Boston. She was in her 90s and nearly blind, and the sound of the water gurgling against the canvas hull took her back to her childhood, canoeing at summer camp. Most of the time I’d lie on my back looking up through the cockpit at the circle of sky rimmed by the coaming, listening to that same sound. When a cool northwesterly was blowing, the air inside the Hooper Bay was still and warm, and redolent with cedar and linseed oil. The rocking of the hull would hold me cradled between wakefulness and sleep.

Over the following decades, I continued to build reproductions of Arctic kayaks. I was drawn to the sleeker and faster Greenland types, learned how to roll them a dozen different ways, and enjoyed paddling them in storms with water washing thick across the decks the deafening roar of the wind in my ears. The Hooper Bay sat under the eaves of my parents’ house for years, dusted green with the pollen of the cedar trees. When I had a house of my own, I kept the Hooper Bay alongside the garage. The canvas covering grew speckled with mildew, and the paint cracked. Eventually I removed the skin, leaving the lashed latticework frame bare.

An artist friend liked the frame and offered to keep it in her studio. The cedar had weathered and turned gray, so before taking it to her I brushed it with linseed oil mixed with vermilion pigment.

The frame stayed suspended above a belt sander and an electric kiln for quite a long time—through a dark decade of divorce, from a time when I kissed my young children goodnight to times when they were grown and I’d go to bed in an empty house; through the death of my mother and chill sea of long-forgotten deadlines and appointments.

I brought the Hooper Bay home when my friend moved out of town, and it lay hidden alongside the house under a black tarp. With the coming of each spring, bracken ferns pierced between its ribs and morning glory spiraled around its chines. I often thought about giving the Hooper Bay a new skin, to paddle away from shore, lie down in the cocoon of wood and canvas, and let the waves rock me into that peaceful half sleep of 40 years ago.

Two summers ago, I took some pictures of the frame set in front of an ivy-covered fence—the vermilion was vibrant against the dark green shingled leaves. I had planned to post the photos with a for-sale ad on Craigslist, but I let month after month slip by. I let the kayak’s color fade. I posted the ad a couple of weeks ago and I got just one response. A few days later the Craigslist buyer arrived and we strapped the Hooper Bay on his roof rack. The frame is gone now, but the best of that kayak remains with me.![]()

Afterword:

Photographs from launch day, summer 1980

Campion’s Apple 16

It all started during the summer of 2015 when I decided that it was time to part ways with MAGIC, my 1962 Alberg 35′ glass sloop. I had spent four years and countless hours restoring MAGIC to her former glory, but two years after re-launching I needed a change. While she was not a big boat by today’s standards, the amount of time and money spent just keeping the boat in the water and in good condition was exhausting. The fact that I lived in central New Hampshire and kept the boat 150 miles away in southeastern Massachusetts only made things worse.

I found myself spending more and more time on a beat-up old O’Day Daysailer that had been following me around since college. My family and I romped around the local lakes and estuaries, sailing hard and often. The only money I spent on her was gas for the car and beer for the cooler. At some point that summer, I realized that I was having as much fun on the O’Day as I was on MAGIC, but with none of the stress. Sure, MAGIC was a comfortable boat that could take somebody sailing for weeks at a time, but I was mostly going out for day sails with an occasional overnighter. I could be doing the same thing on a much smaller boat.

At about the same time, I heard about the Small Reach Regatta, organized by the Downeast Chapter of the Traditional Small Craft Association in Maine. It’s not a race, but a gathering of small, traditional sailing and rowing craft. I have always been drawn to the look of classic boats and when I saw the boat lineup on the Small Reach Regatta website, I knew I had to check it out.

I showed up on the first morning of the event and was able to sail on Mike Duncan’s FRISKY LADY (a Chamberlin 15′ 6″ gaff sloop) and on Geoff Kerr’s NED LUDD, an Oughtred 19′ 6″ Caledonia yawl. I fell in love with the Caledonia but it was a bigger boat than I needed. However, the seed had been planted, and I spent the rest of the summer researching the perfect small boat in the range of 15′ to 18′.

The boat had to be pretty and, while I prefer the look of lapstrake, there is a lot of additional setup and framing required that takes a fair amount of time, so I was looking for a stitch-and-glue design that didn’t require a strongback and associated framing. I also like the classic look of a balanced lug-rigged yawl; and with unstayed spars, balanced lug rigs are really easy to set up for launching. The mizzen makes for easy handling. In spite of the appeal of classic boats, I wanted a fast boat, and a planing hull makes this possible.

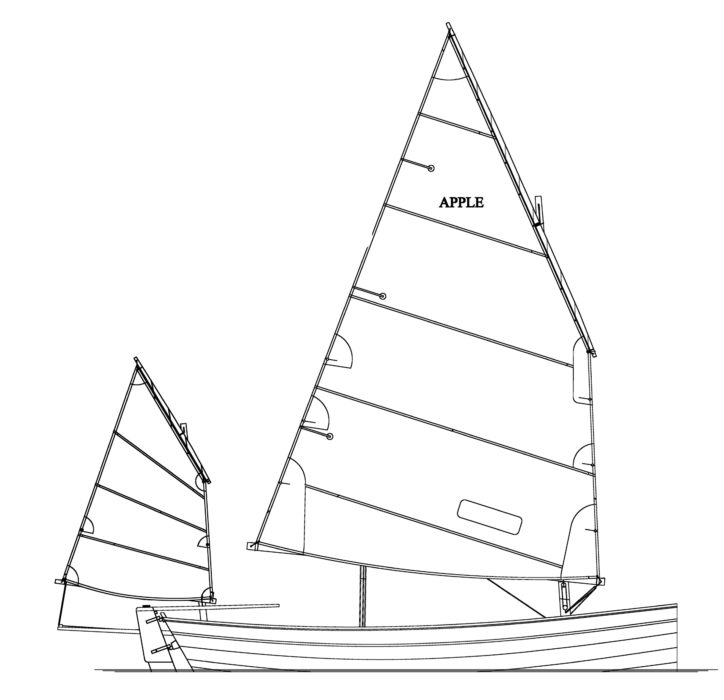

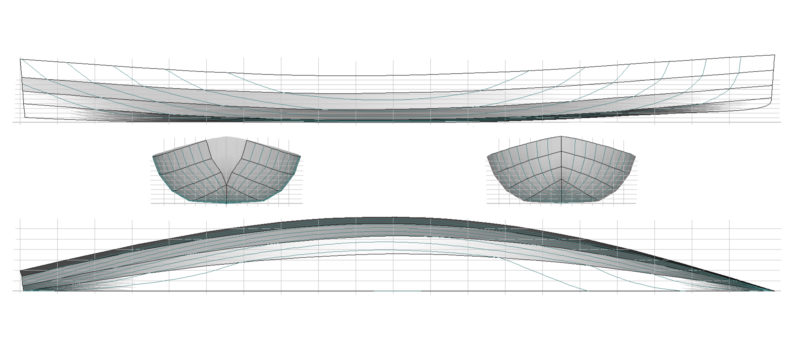

The Apple 16, a five-strake stitch-and-glue balanced lug yawl designed by Thomas Dunderdale of Campion Sail and Design, came closest to being everything I wanted. The classic lines and balanced lug yawl were just what I was looking for and the somewhat flat aft section of the hull allows the boat to get up on a plane. I’m a sucker for a plumb bow, so as soon as I saw pictures of the Apple 16, I knew it was for me.

Photographs by Jacob Bowser

Photographs by Jacob BowserThe plans detail several interior layouts, and provide the option for decked ends . The author designed his own interior with flotation tanks and a removable center thwart.

After several conversations with the designer, I purchased plans and began the build. Thomas was very helpful, answering all of my questions via email or phone.

I didn’t want to wait for a shipment of full-sized printed plans mailed from England; I opted for digital files and took them to a local copy shop and had them enlarged for about $30. I was really happy with the amount of thought and detail that went into the plans; they came with a general construction narrative, a detailed 30-page keyed construction index and at least a dozen schematics for the boat, parts, and interior layout options. For a first-time boat builder, everything provided should be easy to follow.

The included materials list calls for four sheets of 6mm marine plywood scarfed lengthwise for the hull, two sheets of 6mm for bulkheads and interior framing, and one sheet of 9mm for the rudder and additional components.

With a solo skipper aboard, the Apple 16 can, in spite of its traditional appearance and rig, get on plane in a moderate breeze.

While Campion does not currently offer files for a CNC mill, someone savvy with a CAD system should be able to digitize the planking measurements and send them off for cutting to save time. I don’t have easy access to a CNC mill, so I opted to plot the strakes on the scarfed panels and cut them out myself. The plans package provides both a table of offsets and a visual diagram for plank measurements that is very intuitive.

Probably the best thing about building a stitch-and-glue boat is how fast you can make visible progress. Once you cut the strakes from the scarfed plywood panels, assembling the hull is a simple matter of drilling out holes for wire or zip ties (I opted for zip ties) and stitching the panels together. In a single, albeit long, afternoon you can go from a pile of flat plywood pieces to a structure that resembles a boat.

The author could comfortably row the Apple 16 at around 3 knots. His sectional oars, with carbon-fiber ferrules, stow neatly out of the way while sailing.

Of course, it’s not all a piece of cake. Until you get the bulkheads tied in, the entire structure is a bit of a wobbly mess. I cut cradles to steady and align it while I tied everything together. This helps immensely when one is working alone.

The job of taping the inside and outside seams, followed by a layer of 6-oz ’glass on the outside of the hull is rather monotonous. If you’re careful, cleanup should be a relatively minor job and once complete, you can move on to fitting out the interior.

The plans provide layouts for several interiors ranging from a spartan setup of three thwarts, with two doing double duty as mast partners, to a more extravagant layout with decks fore and aft. I deviated from the plans and designed my own interior with built-in flotation compartments and a center thwart that’s removable for camp-cruising.

The boat is quite light, and a solo sailor could add some ballast to stiffen the hull against the press of the sails. The designer recommends adding between 110 to 275 lbs if ballast is needed.

The plans call for a long, open daggerboard trunk to accommodate multiple mizzen sail plans (the larger plan changes the center of effort and requires the daggerboard to be located further aft). Since I was only building the version with the smaller sail plan, I shortened the daggerboard trunk after consulting with Campion.

I also increased the thickness of the daggerboard from 25mm to 33mm so I could build a NACA 0012 foil. I’ve had several opportunities to test performance against other similar designs with balanced lugs and I believe that the foil helps with upwind performance.

All told, the build took me about eight months of working 10–15 hours per week, and I couldn’t be happier with the way it turned out. A single rower with 9.5’ oars can propel the boat at 3 knots when rowing at a comfortable pace, and her sailing ability has exceeded my expectations. Trailering with my four-cylinder Rav 4 is easy.

I’ve had the boat out for dozens of times in a variety of wind conditions, and the boat is really amazing to sail. Having no prior experience with balanced lug rigs, I spent a lot of time researching balanced lug sail tuning and after a bit of trial and error, I opted to go with 6:1 downhaul and 4:1 mainsheet tackle. I used Dyneema line for the downhaul and main halyard to maximize luff tensioning ability.

The Norwegian tiller may take a bit of getting used to if you haven’t used one before, but it is the simplest arrangement for getting around a mizzen mast and has a number of advantages over a conventional tiller.

With the rigging configuration sorted out and making sure the downhaul tension is drum tight, I found that the pointing ability was quite good. Combined with the foil daggerboard, which should theoretically increase lift, the Apple 16 is not far off the pointing angles that a similarly sized Bermuda-rigged boat can achieve. When soloing, I regularly get up on a plane on a reach and hit 8.5 to 9 knots in less than 15 knots wind. Over 15 knots and I put in a single reef, and have sailed in conditions up to 23 knots without being terrified.

We have had four adults out for a sail, and while it is manageable, two of the crew need to sit in the well on either side of the daggerboard trunk forward of the thwart. The 250-lb boat is really best suited for one or two, and each additional crew member reduces the boat’s ability to plane. I have yet to be able to get the boat on a plane with more than two crew on board; I suspect that it would have to be pretty windy to do so. With that said, the boat sails well even with four on board.

The boat is as well-mannered as a light boat can be and is reasonably dry in most conditions. Beating close-hauled into chop over 2’, predictably, tends to be the wettest point of sail. The yawl rig contributes to a very balanced helm on all points with just enough weather helm on the Norwegian push-pull tiller to take any of the play out of the system and allow you to make subtle course corrections.

The Campion Apple is a well-thought-out small boat that is lively to sail and will turn heads in any harbor. It’s a good choice for a first-time boatbuilder with woodworking skills who doesn’t want to spend years building a boat that looks and sails great.![]()

Matt Bowser, a software engineer living in Canterbury, New Hampshire, can’t remember a time when he wasn’t obsessed with boats. He grew up sailing the coast of New England from Rhode Island to Maine and is enamored with the simplicity, ease, and low maintenance of small boats. When he isn’t sailing, building, or fiddling with various boat bits, he’s mountain biking in the forests of New Hampshire and Vermont or trying to get his teenage children to hang out with him.

Apple 16 Particulars

[table]

Length/15′ 10″

Waterline length/14′ 4-1/2″

Beam/5′ 3″

Draft, board down/3′ 9″

Sail Area/123 sq ft

Ballast, if used/110 lbs to 275 lbs

[/table]

Plans for the Apple 16 are available from Campion Sail and Design, based in the UK. Prices are in Pounds Sterling: £65 (approx. $79 USD) for PDF, and £120 (approx. $146 USD).

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

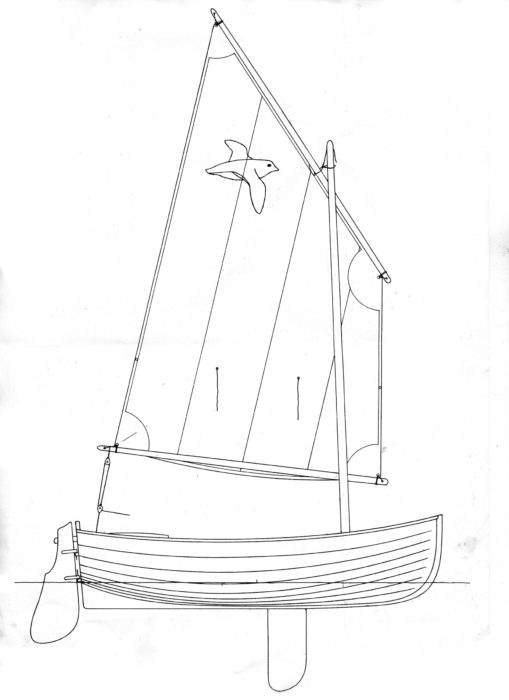

Oughtred’s Auk

The Auk is an Iain Oughtred design that dates back to 1984. He was “just looking at traditional boats and trying to produce an ideal version of an 8′ tender.” It was a smaller version of the Puffin, a 10′ tender he had previously designed; he gave the Auk a generous beam for its length and a particularly pronounced sheer. “I tend to agree with Uffa Fox that you should have a good strong sheer because it is stylish and it helps keep the water out,” he said. After selling about 250 sets of Auk plans, he redesigned it about 10 years ago to be “a refined version of the same thing with a couple of inches more beam,” and has sold a further 116 sets of plans since then. It is designed primarily as a tender with carrying capacity of three or four people “in sensible conditions,” but he gave it a balanced lug rig for sailing.

When Sam Manners enrolled at the Boat Building Academy in Lyme Regis, England, he decided he would like to build an Auk, but was keen for his to be a bit longer. Iain offers two lengths for the Auk with a little stretching by spacing the five molds, transom, and stem 2″ farther apart to increase the length of the Auk from 7′11″ to 8′11″, but Sam wanted to go a bit longer. He decided to space them 2-1/2″ farther apart than designed, which would give him an overall length of 9′2″.

Sam Manners

Sam MannersThe interior is functional, uncluttered, and easy to clean and maintain.

Printed plans include 12 pages consisting of an introduction, four pages giving basic knowledge regarding traditional and glued clinker construction, the table of offsets, and templates for the full-scale half molds. The plans are not available digitally.

“However good the plans and templates are, we always advocate lofting,” said course tutor Mike Broome, “as it allows any errors on the designer’s part to become apparent. Also, if you are stretching the boat, it’s the only way to get it all faired up. It also means you can lift patterns and templates for any elements of the fit-out, etc.”

After lofting the lines full-size, he and fellow students set to work by setting up five 1/2″ plywood temporary molds and the 7/8″-thick khaya transom upside down on a low workbench to give a comfortable working height. The centerline structure was then added. This consisted of the sapele hog 3/4″ thick and 3-1/4″ wide to allow for the daggerboard slot, although for the rowing-only version noted in the plans it would only be 2-3/4″ wide. The aft end of the hog had to be steamed to cope with the rocker. The curved inner stem (or apron) was laminated from nine layers of 1/8″-thick sapele.

The planks are 1/4″ BS1088 sapele plywood. The garboards were laid over the hog, meeting each other in the middle and glued with epoxy. The rest of the planking was epoxied along the 3/4″-wide laps using shop-made planking clamps known as “gripes,” and temporary screws at the hood ends to hold everything in place while the glue set.

Nigel Sharp

Nigel SharpThe standard arrangement for sailing is a balanced lug sail with a daggerboard. The plans offer another option: a standing lug with a leeboard.

The plans called for eight strakes, and that is what Sam and his fellow students fitted, but they had trouble fitting the planks around the turn of the bilge. There were two planks on each side that had get around nearly 90 degrees. “It took many attempts, and we probably got through a full sheet of plywood just trying to get that curve,” Sam said, “but we managed to get it eventually with the aid of double the number of gripes. If I built another one I think I would fit three planks round that curve.”

Once the planking was completed, a 1″-thick sapele skeg and keel were fitted as well as a pair of 2′ x 3/4″-square bilge runners, followed by the outer stem (made up from three pieces of sapele scarfed together) which sealed the end grain of the plywood planks at the bow. The daggerboard slot was cut through the centerline. An epoxy sealant followed by epoxy primer were then applied to the outside of the hull.

When the hull was flipped upright and the temporary molds were removed, it “wobbled like jelly,” but before any stiffening structure was fitted, the excess epoxy was scraped away and the inside of the hull was sanded. Once that somewhat laborious process was completed, four 3/4″-thick sapele floors were fitted.

The daggerboard case is made of ¼” plywood stiffened by a 2″ x ¾″ khaya framework and braced with the 7/8″-thick khaya center thwart. Rather than having continuous risers, the forward and central thwarts bear on short supports, while the stern seat—made up of seven fore-and-aft boards laid out in an attractive fantail pattern—are supported by a 1-1/2″ x 3/4″ athwartships bearer and a pair of cleats on the transom.

The boat’s outwale is made up of three pieces: first a rabbeted section of khaya that covered the end-grain of the top edge of the top plank, then a 1/8″ piece of yellow cedar for aesthetics, and finally another piece of generously rounded khaya, giving a total gunwale thickness of 1″.

Nigel Sharp

Nigel SharpThe volume created by the broad transom helps support a passenger seated in the stern.

Fitted along the bottom edge of the sheer plank, as much for style as for a guard, was another piece of 1/2″ x 3/8″ khaya tapered at the ends.

After khaya spacers to support the inwales for the open gunwale were then fitted, the interior received the same base coats as had already been applied to the exterior, and then three coats of polyurethane paint. The khaya got five coats of varnish. The inwales were installed, and the hull was then turned over for paint and brass keel bands on the centerline, alongside the daggerboard case, and on the bilge runners.

Various ancillary parts were made up: the 1/2″-thick khaya sole boards which bear on the floors, the rudder and daggerboard in 7/8″ khaya, and spars and oars of Sitka spruce. “The instructions and plans were nicely detailed and if ever there was any small confusion, we were able to figure it out,” said Sam. “We didn’t need to refer to Oughtred’s Clinker Plywood Boatbuilding Manual.”

The boat was launched on a gray, at first windless, day in June. Sam and the two students who had most helped him with the build, Sam Ferguson and Amaya Hernández, climbed aboard and rowed out of the Lyme Regis harbor; the tanbark lug sail that Sam had made hung limply. After a while I replaced Sam Ferguson and a gentle breeze soon came off the land. We then enjoyed a brief sail as the boat slipped along nicely in the flat water.

It didn’t seem too crowded with three of us on board until we tacked. That would have been much easier with two, but maybe with a little practice three people could negotiate a better procedure. Starboard tack was the favored one for the balanced lug rig, but any loss in performance on port tack when the sail was pressed against the mast was imperceptible.

Nigel Sharp

Nigel SharpThe Auk’s full bilges make a burdensome hull with good capacity. The stretched version here has room and freeboard enough for three; the 7’10” unstretched version will carry two comfortably.

At one point, a speedboat came close by at about 20 knots, and Sam and I watched the approaching wash with some trepidation. When it arrived, however, we were boat pleasantly surprised with how easily the Auk coped with it, giving us no cause for alarm. The boat was much more stable than we expected.

We needed to get back into the harbor before the tide went out, so we dropped the sail and I rowed us back in. The three of us we were able to keep the boat on an even keel with Sam one side of the tiller in the stern and Amaya on the opposite side in the bow. At first, I was worried that there might not be room for my fairly long legs, but I soon found I could use the stern seat as a stretcher. Although the 8′ oars felt too long for me, and the leathers were too thick and prevented feathering, I could tell that the Auk will be a nice, easy boat to row. Sam’s Auk will be used mainly as a tender for his parents’ 32′ sloop. He plans to fit a rope fender around the Auk, using some old heavy-duty hemp, while her sailing rig will stow in a bag strapped to the front of the mothership’s mast. She will certainly be suitable for her role as a tender, and the option of also using her for exploring rivers, bays, and coves under oar or sail will be a welcome addition.![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boat building and repair industry, and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Auk Particulars

[table]

Length/7′10″ or stretched to 8′10″ (as built here, 9′2″)

Beam/4′

Depth/19″

Weight/60 lbs

[/table]

Plans for the Auk are available from Oughtred Boats. Listed prices are in Australian dollars: $134.66 AUD (approx. $90.58 USD) for plans, $1235 AUD ($830.75 USD) for kits.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Running on Sunshine

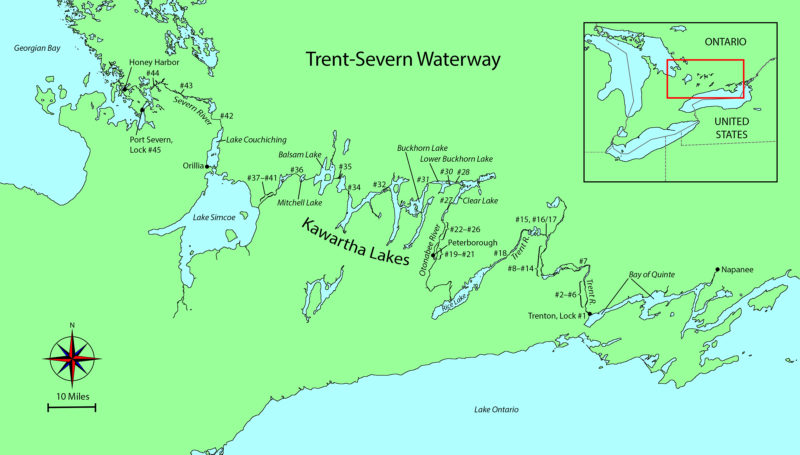

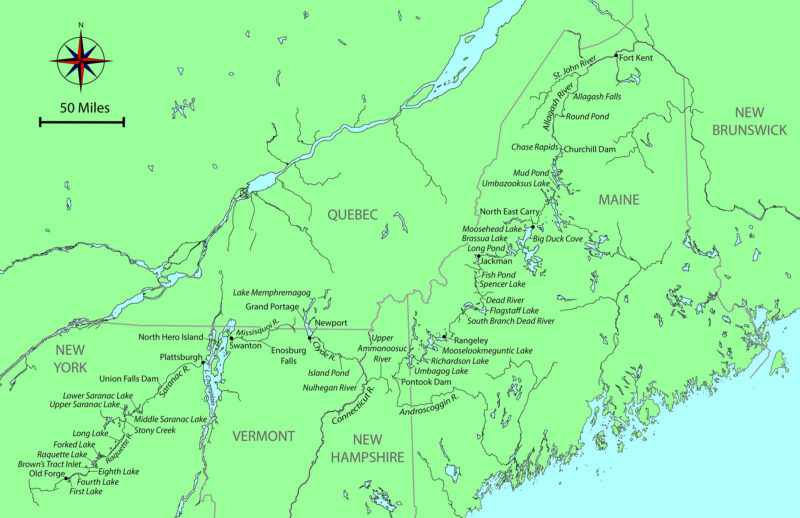

In 2018, I left my home dock on the Napanee River in southeast Ontario and headed for the Trent-Severn Waterway, a 240-mile chain of rivers, lakes, locks, and canals leading all the way to Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay. My challenge would be to do this trip solo in SOL CANADA, a small wooden boat I’d built to be 100 percent solar-electric powered.

I knew of only one solar-electric boat that had traveled the full distance from Lock 1 in Trenton to Lock 45 in Port Severn, so they were the first. I’d be the first Canadian using only the sun to charge my batteries.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorSOL CANADA’s canopy would not only keep me out of the sun and rain (mostly), but the four solar panels it carries would also generate all of the power I’d need for the trip.

SOL CANADA’s hull was based on the Greavette Dispro, manufactured by the Disappearing Propeller Boat Company from 1915 to 1958. An enclosed motorwell holds a Torqeedo Cruise 2.0 electric outboard, and in a compartment under the seats are four 6-volt batteries wired in series to provide 24 volts with a capacity of 221 amp-hours. I expected the boat to be capable of an average speed of 5.4 mph. The batteries are charged by four flexible solar panels on the canopy. They have a rated output of 860 watts.

At 7:30 a.m. on the morning of August 19, I motored away on what was supposed to be a sunny day with a light following breeze from the east. I headed down the 6-mile stretch to the mouth of the river, then along the Bay of Quinte to the city of Trenton—a distance of 31 miles.

There was a haze in the sky that cut the solar production by half, but on the bay, the easterly breeze was now a 12-mph tailwind and SOL, doing a bit of surfing, made good headway to the mouth of the Trent-Severn waterway at Trenton.

Two miles north upriver, the only boat heading upstream, I arrived at Lock 1 and went through immediately. The lockkeeper notified the next lock, just 3/4 miles away, that I was coming and its gate opened for me as I approached. There are three more locks in the first 6 miles of the Trent Canal, and all of them were expecting me with the gates open.

By the end of the first day of my trip, I had traveled 42 miles and had made it all the way to the top of Lock 5. With my home-made fabric walls rolled down into camping mode, SOL CANADA was ready for peaceful night’s sleep.

At 6 p.m. I motored out of Lock 5, well ahead of schedule. My total distance that day was 42 miles and my battery bank was at a 77 percent charge, good enough to carry me the next day if the conditions were poor. I was the only boat stopping for the night in a still-water cove above the lock. The lock master gave me a key to the staff washroom, kitchen, and the shower. Back at SOL, I prepared for the night by folding the seats down to make my bed and rolling down poly-tarp from the perimeter of the canopy. My enclosed sleeping quarters would get some peculiar looks, but they proved to be very comfortable.

On the morning of the second day, just north of Trenton at Lock 5, my good friends Ed and Sandy arrived by canoe to bring me a hot coffee and a homemade muffin. They just live 1/4 mile up river and frequently paddle this stretch of the Trent River.

The morning sky was clear, and the sun quickly warmed SOL’s enclosure. Ed and Sandy, old friends who live close by the lock, arrived by canoe bringing coffee and a muffin. After saying goodbye and packing my things, I rolled the curtains up and SOL was ready to go. It was such a sunny day, I figured I could maintain a good pace without drawing the batteries down. I got to Lock 6 at Frankford before the morning got busy with boat traffic.

All along the river, weeds choked the shallows, and islands of free-floating weeds ripped up by boats clumped together on the surface. I can see the power gauge jump when weeds get pulled in between the prop and the housing. Although I’d made a prop guard, weeds were still a problem, but I could throw the motor into reverse and almost always shed them. Sometimes I’d have to stop and tear them out.

When I emerged from Lock 6 at Frankford under a bright clear sky, the lock opened on water foul with weeds. Just 1/2 mile ahead they’d bring me to a stop.

Just past the Frankford lock, in a narrow quiet channel with cedar trees hanging over the bank, I felt the motor vibrate with weeds tangled in the prop. Shifting into reverse did not get rid of them, so I put the controller into neutral. As I removed the weeds, I did not notice that the breeze had pushed me close to shore. When I realized what was happening, I quickly twisted myself back into my seat to take control, and in my haste my elbow hit the throttle. The boat lurched forward into overhanging branches, and the 100-lb canopy came crashing down beside me. My shouts echoed across the channel. I should have pulled the magnetic kill switch before working on the prop.

I thought the trip was over. I made my way back to Lock 6 where two lockkeepers and a boater lifted the canopy up while I reinserted the front posts and drove screws back into the holes they’d been torn out of. One solar cable at the back had been pulled apart, and I had to splice it back together. After two-and-a-half hours, the boat was a bit battered but operational. I could keep going forward.

My packs containing my supper provisions and gas stove were on the picnic table as my boat was moored for the night at the top side of Lock 8, Percy Reach. After eating, I finished the repairs to the canopy supports.

I finished the day at Lock 8, a quiet site with campsites. I removed the screws that had been torn out, added glue to the holes, and reinserted the screws. I cooked up some spaghetti on my camp stove and was in bed by 9 p.m.

Morning came with heavily overcast skies; the forecast called for rain later in the day. So much for getting ahead of schedule.

I reached Lock 9 before its keepers arrived at 9 a.m. While I waited, I walked around the grounds. Set between farmlands to the east and a wooded island to the west, it would have been a very peaceful place to spend a night. Like many of the locks on the lower part of the Trent, this one was isolated from towns, their bridges, and their traffic. When the staff arrived, I spoke with the lock master; he mentioned he had a friend named Peter who was an editor and interested in stories for an online newspaper. I provided my phone number in case he wanted to do a story on my boat.

Just 1-1/2 miles upstream from Lock 9, I passed through Lock 10. Locks 11 and 12 were piggybacked one on top of the other for a combined lift of 48’. After about two hours on the water, with the rain pouring down and driving in from the starboard side, I got a call from the editor, Peter Fisher, and arranged to meet him the following morning. After seven locks and 12 miles in the rain, I arrived at the top of the two-lock flight of Locks 16 and 17. Lock 17 was not the nicest place to stay. The washroom was on the grubby side and the weather put me in a bad mood.

In the morning ,I had time to kill before meeting with Peter at 11 a.m. When he arrived, I invited him aboard for a ride on the boat as he interviewed me. I was back on my way at about 1 p.m., headed for Lock 18, 15 miles upstream.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

The sky was overcast and the solar panels would not be generating much power. I’d have enough charge to get to Lock 18, in the town of Hastings, more than 14 miles upstream; but the following day, to cover 37 miles to Lock 19 at the outskirts of the city of Peterborough, I’d need to start out with fully charged batteries and have sun along the way.

As I was approaching Lock 18, a motoryacht, NEPENTHE, passed by and entered the lock ahead of me. After exiting, we both docked at the concrete wall on the north side of the river. NEPENTHE’s owners, Paul and Jill, and their passenger Tom, are “Loopers,” traveling the 6,000-mile-long Great Loop, a chain of waterways passing through the U.S. and Canada via the Mississippi River and the Intracoastal Waterway. Dale and Ann aboard UTOPIA, another yacht stopped for the night, were also Loopers. For dinner, the six of us walked to a nearby eatery . The yachters asked if I had seen a kayaker named Steve who was paddling the Great Loop. I hadn’t, but said I’d keep my eyes peeled for him.

When morning broke, the day promised to be mostly sunny, just what I needed to get to the Peterborough lock. I left just past 8:30 and headed 5 miles west to Rice Lake, a 20-mile-long shallow lake that can be very rough when a stiff westerly blows, exactly what I faced that morning. SOL crashed over the waves, and the wind howled and made the canopy sway. The quiet electric motor made noise of the elements seem so much louder.

After 17 miles on the lake, I turned north into the Otonabee River where I found shelter from the wind, even though I was traveling against a strong current of about 2 mph. At the Bensfort Bridge, 7 miles upstream, I met with another reporter, Jason Bain, of the Peterborough Examiner. The riverbank where he was standing was rocky, so I anchored 30′ from shore for the interview. We talked for a while, and as I was getting ready to leave, I tried to pull the anchor up, but it wouldn’t budge. I had to cut the rode. Jason felt bad that I had to lose the anchor and promised to replace it.

It took me about 4 hours to make my way to Lock 19 into Peterborough and the lockkeeper there presented me with a new anchor and rode left for me, courtesy of the Peterborough Examiner. Jason called; I thanked him and told him the story of the anchor. In 1964, my father was working on a hydroelectric plant at Niagara Falls. A coffer dam constructed above the falls exposed the riverbed, and among the artifacts lodged in the rocks were two anchors. My dad brought them home and the one I’d lost was one of them. Jason felt even worse that the anchor was a family heirloom, but month later, when I was back at home, Jason called again. Two SCUBA divers had heard about the missing anchor, found it snagged, and sent it to me.

Just 3/4 miles up from Lock 19, I stopped for the night at Lock 20 in the middle of Peterborough. My cousins Carl and Melba took me out to dinner.

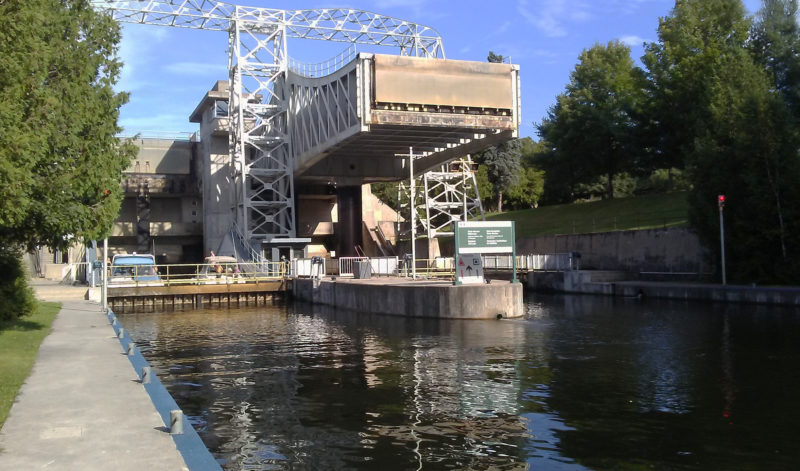

With my cousin Carl aboard, we motored into the Peterborough lift lock, Lock 21. This is the largest of its type in the world, and lifts boats 65′ in a just a couple of minutes. At the top there is a panoramic view of the city of Peterborough.

In the morning, Carl joined me to ride up 65′ at Lock 21, the Peterborough Lift Lock, the largest hydraulic lift lock in the world. The locks are a side-by-side pair of 140′ by 33′ tubs called caissons, each sitting on top of a cylindrical ram, 7-1/2′ in diameter. When a caisson reaches the top, it stops a few inches below the water level of the upper canal and takes on water when the gates are opened. The additional water makes it the heavier of the two, and as it descends, water in its ram flows to the other ram to drive the lower caisson upward.

After the lift, I left Carl at the docking wall and chased after the other boats leaving the lock to join them in the 4-1/2-mile-long succession of five locks. If I fell behind I’d have to wait for the next opening, so I zipped along at 5 1/2 mph, figuring I could spare the extra batteries power.

About 14 miles from Peterborough, Lock 27 was the end of the Otonabee River and the entry to the Kawartha Lakes, a chain of a dozen lakes traversed by the waterway. The lock is in a park-like setting with a 200-yard-long island separating it from the rapids and dam where the Otonabee River rushes by.

After another good night I arose to yet another overcast day. I set out northbound on Clear Lake turned west at Stony Lake and passed through two of Lower Buckhorn Lake’s locks, finishing up at Lock 31.

By now, the interview with Jason had been published and I was hailed by boaters and people on shore. People in cars honked and waved at me.

At the west end of Lower Buckthorn, I arrived at the downstream side of Lock 31 and secured the last spot on the wall. It was a Saturday and there was a festival around the lock with live music. I made the rounds until the rain started and I retreated to SOL for the night.

On Sunday morning I headed south along Buckhorn Lake, a 1/2-mile-wide wooded corridor dotted with summer homes and bristling with finger piers. The water is utterly clear but looks black where it is deep. The land around the lake is blanketed with tall pine trees and dotted with granite outcroppings. The waterway turned west through a cluster of undeveloped islands and then north along Pigeon Lake. By midafternoon I reached Lock 32 at Bobcaygeon, a little town in the middle of cottage country. I’d only traveled 17-1/2 miles, but the next lock was another 18 miles away, more than I wanted to take on.

Bobcaygeon was a beautiful spot to stop for the night. There were lots of people around while I tied up the boat, many of whom had read about my adventure in the paper and asked about SOL. I took a walk around town and when I returned I saw a lone kayaker in the lock, his decks loaded with gear. I yelled down, “Are you Steve?”

“Yes,” he answered. I had found the kayaker paddling the Great Loop. After he left the lock, I gave him a hand unloading his gear and helped him set up camp. Steve Chard, 60 at the time, is from England, and had served in the ’70s on British nuclear submarines. We went out for supper and he told me about spending the Cold War years aboard a sub.

On Monday morning, Steve got a 30-minute head start on me, and it took me a couple of hours to catch up and pass him. We were both planning to go to Lock 35, in the rural community of Rosedale, for the night. I arrived at the lock well before he did and as I waited for the green light to enter, I heard the lockkeeper on the loudspeaker call out, “Come ahead, Phil.” Word of my journey had spread and I was now getting personal service.

I set up for the evening above the lock, which is far from any town and hemmed in by old trees, but not necessarily primitive: it had showers and free wi-fi. Steve arrived, set up camp, and we cooked supper together—a spicy Uncle Ben’s rice dish beefed up with a package of partly dehydrated steak chunks. Our meal was interrupted by our cell phones sounding a weather alert: there would be a tornado watch for the next few hours. When the rain started coming down, Steve and I took shelter. We soon had plenty of company. The all-clear notice came at midnight; Steve headed back to his tent and I got aboard SOL.

In the morning, I headed out onto Balsam Lake for a 5-mile crossing. The wind was blowing from the southwest at about 18 mph. The marked channel was exposed , so I veered north to take shelter in the lee of Grand Island, a mile-long, sparsely inhabited island in the middle of the lake. That was fine for half of the crossing, but west of the island, beyond the lee, whitecaps splashed over the bow. I slowed down to limit the spray. At the end of the crossing, with only 1/4″ of water in the bottom of the boat, I entered a quiet, 30-yard-wide canal.

After crossing the very rough water of Balsam Lake on my 10th day underway, I entered into a very long stretch of hand-dug canal where some of the original tailings still remain piled high on the banks. I was relieved to be out of the strong west wind that plagued me on the lake and have this peaceful canal all to myself.

Two long stretches of canal here—separated by the 1-1/2-mile crossing of Mitchell Lake—were dug by hand, straight as an arrow, just wide enough for two boats to pass. Mounds of stone piled by laborers along the banks well over a century ago are still there. I savored the solitude and silence. The only sound SOL makes is the murmur of her bow waves.

Lock 36 is the Kirkfield Lift Lock, slightly smaller than the one in Peterborough, and SOL, the only boat locking through, was dwarfed by the 140′-long caisson. After the gate closed, we dropped 49′, the first descent after gaining about 600’ in elevation since leaving Trenton. The rest of my journey would be downstream.

After I exited the Kirkfield lift lock, the caisson on the left took on two boats and had its gate closed behind them, ready to be raised.

UTOPIA was moored for the night at the downside wall, so I pulled in astern. Dale and Ann invited me aboard, and while we were swapping stories, Steve emerged from the lock and paddled over to join us for barbecued bratwurst.

Steve was in the lead as we approached the Gamebridge Lock 41, the last lock before heading out onto the sometimes treacherous Lake Simcoe.

Steve and I set out from Kirkfield and descended five locks over 11 miles of canal, stopping at Lock 41, which lies just 1-1/2 miles from Lake Simcoe. A sign at the lock warns boaters to be wary and check weather conditions prior setting out on the 14-mile crossing of the lake. Its shallow depth and broad fetch can make it extremely hazardous, with waves that can reach 6′. Steve and I planned to be on the lake by 7 a.m., before any wind came up. I’d follow the channel right out to the center of the lake; Steve would paddle along the shore, which would take considerably more time.

I entered the lake under a dark, overcast sky with a northeast wind already starting to blow. With SOL running at 4-1/3 knots it would take 3-1/2 hours to reach shelter in the waterway through the city of Orillia. As I made my way farther into the lake, the waves grew, probably only about 2′ high, but they pitched SOL back and forth. The canopy was swaying, and to stabilize it I braced with my legs and held on to it with my left hand, like a guy driving down the highway, holding a mattress on the roof of his car. I slowed down to about 3-3/4 mph to keep breakers from crashing over the foredeck. By the time I got to Orillia, my legs were like rubber, but SOL hadn’t taken on too much water.

Beyond Orillia, I navigated a narrow gap into Lake Couchiching, a 10-mile passage, but in that narrow lake the water was merely choppy. In just over two hours I was across and headed up 1-3/4 miles of canal to Lock 42, nestled in a dense forest of white pine, beautiful and quiet. The wind blowing through the trees rustled of the needles and imparted a fragrance to the air. Steve sent me a text saying his trip around Lake Simcoe had been slow and he would spend the night in Orillia.

After I passed through Lock 43 at Swift Rapids, I could see the magnificent structure of the lock and the hydroelectric dam adjacent to it.

Just 32 miles separated me from Lock 45 at Port Severn, the gateway to Georgian Bay. Going downstream now, SOL was at times making 6-1/4 mph. Only two locks remained. The towering Lock 43 at Swift Rapids lowered me 46′, and Lock 44 at Big Chute is not really a lock but a marine railroad. A huge flatbed car on train tracks rolled down a slope into the water, and I drove SOL over it, stopping over a pair of slings that cradled the hull. The car carried SOL and a handful of other boats 185 yards over a rocky hill to the other side and back into the water. The ride was a bit bumpy and not as fast as a lock.

The so-called Lock 44 at Big Chute is actually an overland marine railroad, the only one on the Trent-Severn waterway. The adjustable straps can securely hold almost any hull shape, but even so it is a bit of a bumpy ride. (This picture is from is my second visit, on the return part of the trip.)

I cruised the final 8 miles through a chain of irregular lakes to Port Severn, where I tied up for the night at one of the docks near the entry to the lock.

On a beautiful Saturday morning I lined up for the lock before 9 a.m., bound for Honey Harbor. After passing through, I entered the channel, threading between countless islets and rocky shoals on the fringe of Georgian Bay. A dozen miles north, I arrived at Honey Harbor, and after a stop for a lunch of a burger and fries, headed back to Port Severn. There I tied up near a harborfront restaurant for the evening. Thunderstorms were predicted, and while I was in the restaurant the storm hit. Forked lighting struck all around, one flash and thunderclap after another.

I waited until the storm passed before returning to SOL for the night.

My plan for the next day was to start my journey back home along the way I’d come. I was now about three days behind schedule, with unstable weather predicted for the next four days.

I headed out in the morning under an overcast sky and a destination of getting to Lock 43, Swift Rapids. The sky cleared and by the time I got there it was a sunny, hot day. I moored at the top side of the lock and set up camp. The weather forecast for the coming days was not encouraging, and I’d surely have trouble on Lake Simcoe on my return crossing. I decided I would go only as far as Washago at the north end of Lake Couchiching and have my son-in-law pick me up there at the Washago town dock.

SOL had navigated 337 miles in 16 days, and I had reached my goal of traveling solo up the entire Trent Severn Waterway from Lock 1 to Lock 45 using 100 percent solar energy—a first as a Canadian and a first for a solo skipper. I’m happily satisfied with that.![]()

Phil Boyer retired in 2017 after working 38 years in R&D in the telecommunications industry. He now keeps busy teaching karate at two local clubs and building boats. He has been around boats his whole life, starting with paddling as a kid. At age 11 he built a sailing pram with a bit of help from his father. In 2006 he began building solo canoes and now has four of them, featured in the August 2019 issue. Phil’s interest turned to building SOL CANADA, his solar-electric boat, in 2015. His next build will be a solar-electric version of the Power Cat he read about in the March 2016 issue of Small Boats Magazine.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Four Practical Tips

A Mobile Thickness Planer

Photographs and videos by the author

Photographs and videos by the authorMy planer’s first set of wheels was a set of chair casters inserted in holes in the 2x2s attached to the base. Here one of the 2x2s is clamped to a dolly. The 2×4 being planed is pushing against the door at the back of the shop as the feed rollers drive the planer forward.

When I built my 19′ decked lapstrake canoe, my shop was in a cellar not quite 30′ long, so working with 20′ lumber for the keel and gunwales was a bit awkward. I could rip planks on my table saw by making a partial cut, stopping the saw, and flipping the plank around to finish the cut from the opposite end. A thickness planer can’t easily accommodate stopping, removing the lumber, and starting again, so I put mine on wheels. I’d start it up on the far end of the basement, feed the lumber in, and when the stock hit the wall, the planer would propel itself across the shop floor. It left a trail of chips behind it, but that was before I had a dust collection system so I had to sweep up anyway.

Coiling Tie-Down Straps

A figure-8 coil keeps tie-down straps in a compact, twist-free package.

Tie-down straps with cam buckles are very tidy devices for holding kayaks and canoes securely on roof racks, as well as a host of other applications, but they’re not so tidy when they’re piled in the back of the car waiting to be used. The 1″ webbing common to most straps doesn’t take as well to a loose coil as rope does, and winding them in a tight coil around the buckle requires something to keep them from coming undone. A better way to coil straps comes from the days when computers stored data on punched paper tape. Russ, a former Army intelligence officer turned kayaker, coiled tie-down straps the same way he had coiled paper tape by wrapping it in figure-8 turns around his extended thumb and pinky finger. The figure-8s have the advantage of alternating twists, so when the coil is undone, the webbing isn’t tangled up on itself.

Start by letting the buckle hang down about 3” from the inside of the pinky of your left hand. Feed the strap with your right hand and let the left hand do most of the work. Rotate your left hand, pulling the webbing around the outside of the pinky then keep rotating until you can dip your thumb under the webbing. Reverse the rotation, pulling webbing from your right hand until you can dip your left pinky under the webbing. That’s one figure-8. Repeat until you have all but about 18″ of webbing remaining. Remove the coil from your thumb and pinky and press the buckle into the hollow where your thumb was. Pinch the center of the figure-8s in the middle, fold the tail end at a right angle and take two or three tight wraps around the coil. Tuck the tail end under the last wrap and cinch it tight. That’s it.

Here’s a step-by-step look:

Hang the buckle from your pinky.

Pull the webbing around your pinky and lead it over your thumb.

Bring the webbing over the pinky, finishing the first figure-8.

Continue making figure-8s, always keeping the webbing flat and without twists.

Pull your thumb out and press the buckle into the recess.

Wrap the remainder of the webbing around the middle of the figure-8s.

Tuck the tail under the last wrap.

Cinch tight.

When you need to use the strap, pull the tail end free, undo the wraps, hold the buckle, and drop the figure-8s. The strap is ready to use.

Flag-Folding Tarps

The flag-folded tarp stays wrapped tight by tucking its end into a pocket in the folded triangle.

The method for folding a national flag into a triangle works quite well for camping and workshop tarps and ground-cloths too. The last step tucks the tail end away and the package will hold itself together. Two people can make quick work of folding a tarp, but if there’s no one else around, a spring clamp comes in quite handy. Fold one of the short sides of the tarp in half and clamp the corners to a fixed object. Move to the other end, pull the tarp tight and make the same fold, and then fold it in half again. Return to the clamped end and put a second and a third fold in, making the tarp 1/8th of its full width. Walk the unclamped end out, to tension the tarp again and put the third fold in that end.

Fold one corner in to form a triangle and then “roll” the triangle along the quartered tarp, drawing the fabric tight around the triangle. Stop when you have a leg of triangle (not the hypotenuse) crossing the fabric with at least a leg’s length of fabric remaining. If you have less, back up; if you then have more, fold the remainder to make it about as long as a leg of the triangle. Fold the remainder diagonally to make a mirror-image triangle and then tuck that triangle tight into the pocket formed by the wraps.

Here’s how that looks:

If you’re folding a tarp on your own, have a spring clamp lend a hand.

Start with the tarp folded in half and have the clamp hold the two corners, then fold the other end to halve the tarp.

A second fold quarters the tarp’s width.

The third fold decreases the width eightfold.

Fold one corner on a diagonal to form a triangle.

Flip the triangle along the length of the tarp.

Keep rolling the triangle until you’re close to the end and you have the triangle’s edge square to the tarp. Here there’s not enough tarp left to get to the next squared edge, so the remaining tarp will be folded toward the triangle.

Fold the tail end to make a mirror-image triangle.

Tuck the tail end into the pocket of the triangle.

Throw the flag-folded tarp in the boat if you like—it won’t come undone.

IKEA Slats for a Sleeping Platform

Resting on ledges on either side of the cabin passageway, the slats form a platform for a mattress. White polyester straps fastened to the bottom of the slats keep them together and evenly spaced.

One of our readers, Mike B., asked if I’d ever used IKEA bed slats to create a sleeping platform for overnight cruises. I hadn’t, but just happened to have a spare roll of 27-1/2″ (70 cm) slats for a double bed (Luröy), picked up free off a want ad, and a little canal boat that needed an upgrade for the bulky 3/4″ plywood panels we’d been using to create a sleeping platform in the cabin. The slats are slightly arched and made of 17 layers of hardwood veneer. The space for the slats is 24″ wide, so I had to trim them to fit. They’re joined by a pair of polyester ribbons, so I clamped the slats together and used a chop saw to take a bit off each end.

Stacked together, the slats take up very little room. The ledges for the slats are evident on the seats, on a beam spanning the gap under the table, and on the table itself when it’s lowered to create a queen-sized sleeping platform.

At night, the slats rest on ledges to either side of the passageway between the cabin’s side benches. Stops hold the slat at each end so the whole set is kept in place, just as they are on an IKEA bed, when a mattress is laid on top.

The slats are springy for comfort and are able to support a mattress and a sleeping crew member, just as they would in a bed frame. They’re easily stacked for storage, and take up much less space and weigh a lot less than plywood panels.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is editor of Small Boats Magazine.

You can share your tips and tricks of the trade with other Small Boats Magazine readers by sending us an email.

Rolling Relief for Boat Trailers

For years, decades really, I’ve struggled moving boat trailers around by hand. They always seem to be on grass or dirt; somehow I’ve never had the luxury of paving. My jack wheels can create a lot of serious drag in grass, and they’ll dig holes in dirt when I straighten them out.

A thread on the WoodenBoat Forum, an immensely valuable resource for me, addressed this problem. “Thorne,” the forum member who started the thread, discovered Croft Trailer Supply in Kansas City, Missouri, not a place I’d think of for boating gear. Croft makes a pneumatic-wheel kit with dual 10″ wheels. The plated-steel hubs have grease fittings to lubricate the axle and bushings. Between the wheels is a plated-steel caster plate with a 2″ socket.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe two 10″ pneumatic tires provide lots of support on soft ground. The rope coiled around the winch post is what the author uses to pull the trailer; the jack-stand wheels follow on their own. The grease fitting for the far wheel is visible on the inside of the hub.

Several forum users bought the Croft wheel kit. One was especially interested in using the wheels with a light aluminum trailer that he pushes by hand across sand. At $90, the kit seemed pricey, but the other option I’d considered, a two-wheeled hand dolly, costs about the same. I often need to move the trailer when I’m away from home, and a hand dolly isn’t easy to carry along. So, I went ahead and got the kit.

To fit it to my existing jack stand, I had to cut off the welded-on caster wheel. It could have been done with a hacksaw, but it was much faster to use a grinder with a cut-off wheel, while wearing, of course, gloves, a full face shield, and ear protectors against the sparks and noise.

The caster plate is bolted to the jack-stand’s extending tube, which must be able to rotate for the wheels to pivot. The author’s plastic-pipe adapter, with a small gap where it it split, is visible here.

The Croft caster plate is built to fit a rotating 2″ jack tube. Mine was only 1-1/2″ in diameter, so it needed a bushing to fit snugly. One of the forum users found a bronze pipe of the right size, and there is mild steel tubing with a 2″ outer diameter and a 1-1/2″ inner diameter, but I happened to have a piece of 1-1/2″ PVC pipe. I cut a short length of it, then sawed a slot in it so I could open it up to fit around the tube. The pipe was a bit too thick, so I used my angle grinder with an 80-grit disc to thin it down for a snug fit in the caster-plate socket.

The caster plate’s socket is fitted with a 1/2″ bolt, so I needed to drill a matching hole through the tube and PVC. My 1/2″ drill bit was not up to the task, so I invested in a hardened metal bit at about twice the cost. Chucked into my 20-volt battery-powered drill, it did the job just fine. You need to be careful when drilling through metal: When the bit breaks through the back side, the tip of the bit can catch and set a piece of metal spinning or, if the metal is well anchored, wrench the drill out of your hand.

Even with the two oversize wheels, the jack will still fold away. With the wheels down, I can now push and pull the trailer easily over grass and dirt. Gone is the struggle. I like my new “four-wheel trailer” so much that if I were to get another trailer, I’d move my upgraded jack to it.![]()

Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, has been messing about in small boats for a very long time. He is owned by a dozen or more boats ranging from an International canoe to a faering.

The pneumatic wheel kit is available from Croft for $182.95 plus shipping. Price current as of June 2024.

Is there a product that might be useful for boatbuilding, cruising, or shore-side camping that you’d like us to review? Please email your suggestions.

Dust Deputy Cyclone Separator

We do a lot of sanding for our small-boat restorations and builds, and have relied upon a shop vacuum to collect dust. It does the job but leaves us with bags to empty and filters to clean or replace, which is messy and costly. That changed when we bought an Oneida Dust Deputy cyclone separator to collect the dust on its way to the Shop-Vac. The device uses the centrifugal force of a cyclonic airflow to separate dust and heavier particles, drops the debris into a collection bucket, and sends cleaned air to the vacuum. The collection bucket is easy to empty, and we can use the Shop-Vac without the HEPA bags and even without them, the filter rarely needs to be cleaned.

Photograph by the authors

Photograph by the authorsThe kit for the Dust Deputy includes a pair of 5-gallon buckets: one to gather dust or even water, and another nested below it that has casters and an attachment to the Shop Vac so the whole system can move as one unit.

We bought an Oneida “deluxe kit” that includes the cyclonic separator, a 3′ hose with two elbow adapters, and two 5-gallon buckets, one to collect dust, the other, equipped with casters, to be connected to the Shop-Vac as a “sidecar” to carry the other bucket. The cyclonic separator can also be purchased separately for attachment to different collection buckets and or to fit to larger collection bins. After attaching the sidecar with the hardware provided, we used our ShopVac hose to connect the Dust Deputy to our various sanders, thickness planer, crevice tool, bristle brush, and floor brush.

The Dust Deputy easily handled sanding two coats of epoxy paint off a Sunfish, and when we were finished we had filled about one-quarter of the 5-gallon bucket with dust and had very little material inside the Shop-Vac. For another job, we ran some cypress through a thickness planer, and without the Dust Deputy, the Shop-Vac would have filled a disposable bag almost immediately; with the Dust Deputy we easily collected and emptied the 5-gallon bucket of shavings.

We continue to use the HEPA filter in our Shop-Vac without the HEPA bags to keep the air as clean as possible and have noticed a visible reduction in dust around our shop. Since the filter doesn’t get caked with dust, the vacuum always pulls with full power. We get excellent performance cleaning up the sawdust, wood chips, and other debris that collects on the floor. Any debris that can pass through the 2″ hose, things like pine needles and small leaves and the occasional wood screw, can get through the cyclone. There are no moving parts to reduce airflow or to damage, and the parts are easy to rinse off.

The small Dust Deputy kit, attached to the Shop-Vac, is mobile, and we move it all around our shop and outdoors. It took a few minutes to get used to the extra bucket following the Shop-Vac around, but the superior air quality and cleaner work environment are well worth it. Many folks build a cart and stack the Dust Deputy over their vacuum for a smaller footprint, and to keep all the attachments together.

The Shop-Vac bags are no longer needed, the filter will very rarely have to be replaced, and the Dust Deputy will pay for itself with the savings. We are having fun using it and appreciate the better dust removal, freedom from cleaning the filter, and higher-capacity debris collection.![]()

Kent and Audrey Lewis mess about in small boats on the Emerald Coast of Florida. Their blog can be found at smallboatrestoration.blogspot.com.

The Dust Deputy Deluxe Cyclone Separator Kit is available from Oneida Air Systems for $99.95. The kist is also sold by online andOneida’s selected international retailers.

Is there a product that might be useful for boatbuilding, cruising, or shore-side camping that you’d like us to review? Please email your suggestions.

The Kingfisher Elective

Glenn Joyner, after 43 years as an educator, decided to retire and delivered his notice of retirement to the administrators of John Paul II Catholic High School (known as JPII) in Greenville, North Carolina. Glenn had served as the school’s first principal when it opened in 2010, and a few years later he took on a position as an English teacher. The school community was reluctant to let him go, and at the annual spring banquet one of the school’s benefactors asked Glenn what it would take to get him to stay. Glenn said, half joking, “Build me a boatshop on campus and let me teach boatbuilding instead of English.” The school took the deal, built a campus boatshop, and Glenn stayed on.

Photographs by or courtesy of Glenn Joyner

Photographs by or courtesy of Glenn JoynerRolling the hull upright was an occasion that merited a class photo.

His idea wasn’t completely out of the blue. For the previous four years, he had conducted boatbuilding night classes for JPII students in his backyard boatshop. Each year, between January and May, the students who gathered in Glenn’s barn built and launched a new outboard skiff, starting with a the 15′ Diablo designed by Phil Bolger and Harold “Dynamite” Payson, the 14′6″ Little Moby by Charles Wittholz, the 16′ Shoestring by Karl Stambaugh, and finally the 16′ San Juan Dory by David Roberts. The students were enthusiastic and undaunted when they finished a boat only to discover it was too wide to get it out of the shop. They just took the door off its hinges and cut out a bit of the wall.

The school’s new shop has the luxury of two garage doors, each big enough to move boats in and out without cutting into the walls. The 7’6″-wide Kingfisher has a few inches of clearance on either side.

Glenn’s class at JPII is now among the most popular electives, and he has twice as many students as he had at home. That’s 10 students, a healthy percentage of the school’s 120-student population. They come from a broad spectrum of backgrounds; some have never used power tools or been aboard a boat and very few have even seen a wooden boat.

Trailered up, the Kingfisher is ready for the water. Along the wall are two other student-built boats: a Rubens Nymph and a Payson’s Pirogue.

As the boatshop got up and running, students built a Rubens Nymph, a 7′9″ pram designed by Bolger and a 13′ Payson’s Pirogue designed by “Dynamite” Payson. The Kingfisher 18, built to plans from Glen-L, is the first big boat to emerge from the shop. To power the deep-V plywood hull the school acquired a rebuilt 90-hp Johnson outboard. The fuel tank went out of the way under the floorboards to add to the boat’s stability.

With the project nearing completion, the student builders gather for the finishing touches.

Launch day for each new boat is a big day at JPII, and with the Kingfisher’s 7′6″ beam it helped that the new boatshop has two garage doors. There was no delay getting the boat out and on its way to the water. Once it was afloat, the boat moseyed from the launch out to open water where the throttle could be opened wide. It took off with exhilarating speed, and the V bottom provided a smooth ride. None of the students who were along for the ride had ever gone so fast in a boat.

Teacher Glenn Joyner backs the Kingfisher away from the ramp as class boatbuilders enjoy the fruits of their labor.

Soon after the boat was launched, it was purchased by the parents of two JPII students, but there will be more boats and more students, and it may be a long time before Glenn submits another notice of resignation.![]()

Do you have a boat with an interesting story? Please email us. We’d like to hear about it and share it with other Small Boats Magazine readers.

Explore Your Passion

For a limited time only, save big with this $10 coupon towards a one-year subscription to Small Boats Magazine.

Save $10. Use coupon code:

19THANKS10

We share your passion for boats and we’d like you to be a part of our community. As a member, you’ll be notified of our new content each month, have access to the entire archive of searchable articles (since our launch in 2014), our popular classifieds, and some great new features we’ll be rolling out later this year. Plus, you can cancel at any time.

I Look forward to seeing you on the boat.

Editor: Chris Cunningham

Join the Small Boats community and recieve:

- Unlimited access to our full, searchable archive (since 2014)

- Critical reviews of great small boats

- In-depth tests of gear and techniques

- Small-boat adventure stories

- Post unlimited classifieds

- Converse with passionate readers and our editor through article comments

Subscription Options

Small Boats Magazine is a monthly web-based magazine dedicated to owners and users of boats that can be stored and maintained by the boat enthusiast.

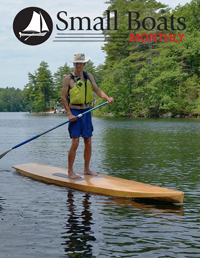

From boats propelled by a oars (like the one pictured above) to boats designed to be powered by paddle, sail, or motor, Small Boats Magazine has monthly content to help you explore your passion for boating.

Explore Your Passion

For a limited time only, save big with this $10 coupon towards a one-year subscription to Small Boats Magazine.

Save $10. Use coupon code:

10SEPTEMBER19

We share your passion for boats and we’d like you to be a part of our community. As a member, you’ll be notified of our new content each month, have access to the entire archive of searchable articles (since our launch in 2014), our popular classifieds, and some great new features we’ll be rolling out later this year. Plus, you can cancel at any time.

I Look forward to seeing you on the boat.

Editor: Chris Cunningham

Join the Small Boats community and you’ll receive:

- Unlimited access to our searchable archive (since 2014)

- Critical reviews of great small boats

- In-depth tests of gear and techniques

- Small-boat adventure stories

- Post unlimited classifieds

- Converse with passionate readers and our editor through article comments

Subscription Options

Small Boats Magazine is a monthly web-based magazine dedicated to owners and users of boats that can be stored and maintained by the boat enthusiast.

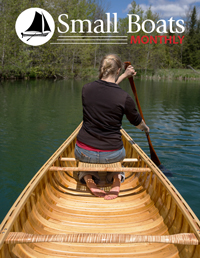

From boats propelled by a paddle (like the one pictured above) to boats designed to be powered by oar, sail, or motor, Small Boats Magazine has monthly content to help you explore your passion for boating.

Explore Your Passion

For a limited time only, save big with this $10 coupon towards a one-year subscription to Small Boats Magazine.

Save $10. Use coupon code:

WELCOME10

We share your passion for boats and we’d like you to be a part of our community. As a member, you’ll be notified of our new content each month, have access to the entire archive of searchable articles (since our launch in 2014), our popular classifieds, and some great new features we’ll be rolling out later this year. Plus, you can cancel at any time.

I Look forward to seeing you on the boat.

Editor: Chris Cunningham

Join the Small Boats community and you’ll receive:

- Unlimited access to full archive backlog (since 2014)

- Critical reviews of great small boats

- In-depth tests of gear and techniques

- Small-boat adventure stories

- Post unlimited classifieds

- Converse with passionate readers and our editor through article comments

Subscription Options

Small Boats Magazine is a monthly web-based magazine dedicated to owners and users of boats that can be stored and maintained by the boat enthusiast.

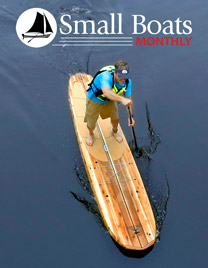

From sail boats (like the one pictured above) to boats designed to be powered by oar, paddle, or motor, Small Boats Magazine has monthly content to help you explore your passion for boating.

Explore Your Passion

For a limited time only, save big with this $10 coupon towards a one-year subscription to Small Boats Magazine.

Save $10. Use coupon code:

10SEPTEMBER19

We share your passion for boats and we’d like you to be a part of our community. As a member, you’ll be notified of our new content each month, have access to the entire archive of searchable articles (since our launch in 2014), our popular classifieds, and some great new features we’ll be rolling out later this year. Plus, you can cancel at any time.

I Look forward to seeing you on the boat.

Editor: Chris Cunningham

Join the Small Boats community and you’ll receive:

- Unlimited access to full archive backlog (since 2014)

- Critical reviews of great small boats

- In-depth tests of gear and techniques

- Small-boat adventure stories

- Post unlimited classifieds

- Converse with passionate readers and our editor through article comments

Subscription Options

Small Boats Magazine is a monthly web-based magazine dedicated to owners and users of boats that can be stored and maintained by the boat enthusiast.

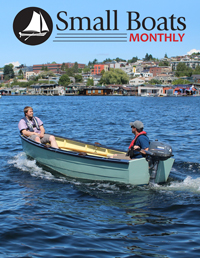

From power boats (like the one pictured above) to boats designed to be powered by oar, paddle, or sail, Small Boats Magazine has monthly content to help you explore your passion for boating.

Subscribe & Save

We share your passion for boats and we’d like you to be a part of our community. As a member, you’ll be notified of our new content each month, have access to the entire archive of searchable articles (since our launch in 2014), our popular classifieds, and some great new features we’ll be rolling out later this year. Plus, you can cancel at any time.

I Look forward to seeing you on the boat.

Editor: Chris Cunningham

Join the Small Boats community and you’ll receive:

- Unlimited access to full archive backlog (since 2014)

- Critical reviews of great small boats

- In-depth tests of gear and techniques

- Small-boat adventure stories

- Post unlimited classifieds

- Converse with passionate readers and our editor through article comments

Subscription Options

Small Boats Magazine is a monthly web-based magazine dedicated to owners and users of boats that can be stored and maintained by the boat enthusiast.

Anchored in Jeopardy

The key to a safe anchorage is the same as the key to prime real estate: location, location, location. When I anchor a boat for the night, I’m almost always sleeping aboard, so it’s not enough for the boat to stay afloat and stay put. The anchorage needs to be quiet and still if I’m going to get a good sleep. Even if a day comes to a quiet close, an anchorage that isn’t well protected from wind, waves, and currents will make me anxious and I’ll wake up frequently to check on the conditions.

I’ve had only four anchorages go wrong (so far). In the middle of a night aboard my dory skiff, I had to sit up in my sleeping bag and row across a cove to get back into the lee after a wind shift; that morning I woke up stranded by a low tide. During an overnight outing in our Escargot canal boat, anchored in the upper reaches of a tidal river, the four of us aboard spent a noisy, sleepless night when the river current accelerated with the falling tide. On my solo in that same boat on the Everett sloughs, I slept well enough but lost my best anchor to a submerged snag.

While those anchorages were annoying, my worst anchorage could have turned deadly. It was in DeHorsey Passage, 17 rowing miles shy of Prince Rupert, British Columbia, on my second cruise up the Inside Passage in 1987. Cindy and I had been underway for a month, rowing and sailing from Puget Sound aboard ROWENA, the Gokstad faering I’d built for the trip. In the days before that anchorage, we had been traveling north along Grenville Channel. We napped during the day when the flood tide was flowing against us and rowed at night when we could take advantage of the slack and ebb tides. At Baker Inlet, 11 miles from the end of Grenville, the water had turned chalky green with the glacial silt flowing out of the Skeena River.

We stopped for the night in a narrow passage like this one, but in the dark near the mouth of a river and dropped anchor in the very brief slack before the tide began to plummet 22′.

We left the channel and stayed close to the mainland shore. Here’s how I described in my journal the events of the night of July 10:

We headed up the mouth of the river. In one south-facing bay we pulled in for a rest stop and in the next bay, facing west, we dropped anchor to wait out the ebb. Cooked up popcorn and dinner and napped on the floorboards with the canopy cloth just pulled up like a blanket.

We woke just before slack and headed north along the edge of the Skeena, tucking into small bays to get out of the wind-versus-ebb chop and the current tumbling over a shoal. As it grew dark, we got ready to cross to DeHorsey Island. We put on foulweather gear and life vests, got the flashlights and new batteries, and took off for a 3-1/2-mile crossing. The moon rose, making it easier to look for the debris carried downriver, but mostly it was a sprint. The navigation-aid lights came on very late. We crossed a noisy chop over a shoal and then hit a tide shear where the current wrapped around Kennedy Island.