When I set out from Mukilteo, Washington, late in July of 1980, the wind was light, barely ruffling the silvery expanse of Possession Sound. I set all sail—the sprit-rigged main, the jib and flying jib, topsail and jib-topsail—but no one would think of GAMINE as a topsail cutter. She was just a 14′ dory skiff, the first wooden boat I had ever built. Aside from her broad plywood garboards, she was traditionally built, with western red cedar planks on both sawn and steam-bent white oak frames. While I’d been day-sailing her for about a year and adding sails one by one until there was no room for more, I’d never done an overnight cruise in any small boat. Now I was headed north to sail the Inside Passage with no particular destination. There was no telling how far I’d get.

photographs by the author and from his collection

photographs by the author and from his collectionMoments before setting out from Mukilteo, GAMINE sits ready with all sails ready to catch what little breeze there was.

Stepping aboard, I kicked aside the tangled tail ends of sheets and halyards, and jammed my boots between the gear-filled 5-gallon plastic paint buckets that took up most of the space in the cockpit. I bore away on starboard tack and set the bowsprit over the low, thickly wooded shores of Whidbey Island. Halfway across Possession Sound I began to wonder how I was going to come about. There were seven sheets to tend to and too much clutter in the way to shift my weight across the crowded cockpit. I gave up on the idea and just held my course until I’d run the dory up on Whidbey’s gravelly eastern flank. I brought the topmast down, and with it the topsail and jib topsail, made some more room for myself in the cockpit, and pushed off on port tack. After a two-mile crossing to Hat Island, I took an afternoon break on a beach fronting a row of single-story summer homes. The wind had been building, so I set out with just the main and jib, and beat across to Whidbey again, came about, and sailed for the south end of Camano Island, two miles to the northeast. I was soon on a beach beneath the headland’s steep, 300′-high bluff. I would have been content to call it a day there, but because the high tide line was right up against the slope there’d be no room to camp. I’d have to make the crossing back to Whidbey. The last tack took me through the wind funneling between the two islands. Spray flew up from the bow, and as GAMINE heeled sharply with the puffs, water poured in over the lee rail. The topmast got loose and was dragged half overboard. I tucked into the lee of the marina at Langley, relieved to be out of the wind and off the water.

With the skiff pulled up on the narrow strip of sand, I set up housekeeping on the pale gray driftwood at the top of the beach. Dinner, it appeared, was not destined to bring order and comfort to the day. After I’d diced onions and russet potatoes, I discovered my camp stove was missing the piece that held the fuel line to the gas flask. I had a pair of pliers in my tool kit and found a nail that I could bend to make a replacement part. The stove, the one I used for winter backpacking, was good for melting snow, but terrible at sautéing. It took just a minute or two to turn the onions brown and gelatinous and char the potatoes, leaving them as crisp as apples on the inside.

I intended to camp on the beach and anchor the boat by means of a long loop of line run through a block attached to the anchor float. It was a method I’d seen described in a boating magazine with a tidy illustration of a boat hauled out to anchor, like laundry on a clothesline. The 200′ of 1/4″ twisted polypropylene I’d bought for the loop was the least expensive rope I could find, but it wouldn’t relax, and 90 minutes of trying to duplicate the drawing in the three dimensions of water, sand, and darkness left me with a wild scribble of yellow rope and emerald-green seaweed. I pulled the mess out of the water and dropped it dripping into the bow to sit until morning, when I would have more light and the wits to untangle it. I’d have to sleep at anchor; in the dark I gathered up the gear I’d brought ashore—goring the top of my foot on the jagged broken end of a driftwood branch in the process.

I sculled the dory off the beach and dropped the anchor. Before I turned in for the night, I used my bleach-bottle bailer to scoop up the water that had come aboard during the day and when I emptied it over the side, the water glowed a bright blue. I dipped an oar in the water, swept it side to side, and the bioluminescence lit it up like a propane flame.

Despite all of the time and effort I devoted to GAMINE’s sailing rig, I’d spend most of my time rowing.

The morning that followed my inauspicious shakedown was mercifully uneventful. The air was still and the water was flat. The sun had but one unbroken reflection, a small bright disk that skimmed the surface of the water alongside of the dory as I rowed. My bare legs began to feel the sting of the sun, so I covered them with my chart. After a stop for groceries at Utsalady, on the north end of Camano, I saw a southerly wind had darkened Skagit Bay to the north, so I raised the topmast and set sail. Beyond the glassy lee of the island, the wind filled the sails and the topmast bent forward. The tide was with me, too, and GAMINE sped toward the Swinhomish Channel. I scanned the land ahead looking for the entrance and saw only a rock jetty. Just when I thought I’d have to steer west to parallel the rocks, I saw a gap. It was only 10’ wide and water was pouring through it. I steered for the middle and the current spat GAMINE out on the other side. The wind skipped over the hills guarding the waterway, so I dropped the sails and took to the oars. The current was running about 3 knots, so there wasn’t much work to do.

As I rowed out of the north end of the channel, the colors of the sunset left in their order: red and orange first, lavender and indigo last. A full moon illuminated Padilla Bay in monochrome and spilled its mercurial light in a streak upon the water.

The tide was falling when I pulled GAMINE on a broad tide flat outside of the Anacortes marina. I set my alarm to wake me before the morning’s flood would lift GAMINE from the slick carpet of seaweed around her. I’d had a long row and fell quickly asleep.

At 2:30 a.m., the din of an unmufflered car engine woke me. The grass on the crest of the bank above the beach shone green as the roar grew louder and the bright circles of the car’s headlights popped above the crest and blinked out, leaving only the glint of the moon in the chrome grill-work. The doors opened, and the figures of six teenage boys arrayed themselves along the bank.

I waited for the inevitable.

“Look, there’s a boat!”

“No way, man. It’s a rock.”

I tried to look more like a rock.

“It’s a boat. Let’s take it for a ride.”

The six scrambled down the bank and stumbled across the slick rocks. When they were just a few yards away I sat up in the stern. The rising of my mummy-bag-wrapped figure brought them to a quick stop.

“What are you doin’ here?”

“Trying to get some sleep.” They lined up around the gunwales, three to port three to starboard. They asked about my row and looked over the equipment in the boat.

“You alone?”

“Yes.” The boat was too small to lie about the size of the crew.

“Well that’s cool” said one of them. Then he told the others, “Let’s let him get some sleep.” Five walked away from the boat. The sixth, standing unsteadily over the port tholepins, stared at me. He turned and called after the others.

“Let’s kill him! Hey you guys, let’s kill him!”

The five ignored him, scrambled up the bank, and ducked into the car.

“Aw, come on, let’s at least throw some rocks at him.” The sixth finally returned to the car. Its engine blared and the roar echoed from the flanks of Cap Sante; the car disappeared, leaving a cloud of dust that glowed red in the shine of its taillights. I did not slide back down into the dory but sat in the stern with my eye on the shore. I waited for the tide.

I was afloat at 4:30 a.m. and eager to get away, even though dawn was still a long way off and the air was quite chilly. With my sleeping bag cinched up under my armpits, jacket over that, and a paper grocery bag for a hat—I couldn’t find my real hat—I started rowing. I couldn’t pull hard because my fingers were quite tender from the previous day’s row. The north end of Anacortes was crowded with shipyards, marinas, and commercial vessels but I found a gentle slope of sand where I could come ashore. I jogged into town to shop for breakfast and a roll of first-aid tape. Before I shoved off I put wraps of tape, two dozen of them, around my fingers and thumbs.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

I left Anacortes on the ebb tide, headed for the San Juan Islands. The southwest wind was pushing a fog bank around the distant forested summits of the archipelago, so I took a more northerly course toward Thatcher Pass to avoid the fog, but I had misjudged the strength of the ebb. The tidal exchange was not great, but the flood tide pushes 130 miles up into the far end of the Strait of Georgia, and all that water has to strain back through the San Juans. Crossing Bellingham Channel and Rosario Strait pushed me south much faster than I could compensate for the drift. I cleated the sheets to keep the sails pulling and began rowing to avoid getting swept into the fog. For the last two miles I was rowing due north as hard as I could, straight into the current, with the oars dully hammering my cadence against the oak thole pins. When I reached Thatcher Pass I tucked into a small cove to catch my breath before heading west again.

Well protected from wind and tides, my passage through the middle of the San Juans went smoothly. I made my last stop in the archipelago at Reid Harbor, and tied up on the Stuart Island State Park dock. With a bit of time on my hands before crossing into Canada, I went through my gear and left two of my 5-gallon buckets, filled with things I could live without and that campers would be glad to have, at the top of the stairs leading down to the dock.

I left Reid Harbor at 6:30 the next morning, rowed the mile and a half east to its mouth, turned west, and then set sail for Sydney, British Columbia, due west. I had a fair wind and GAMINE cut a wake of white froth across Haro Strait at slack tide. The nine-mile crossing slipped easily by and by 9:30 I’d cleared customs and began working my way north through the Canadian Gulf Islands.

I spent the rest of the day sailing, and after eight hours underway I reached Wallace Island, a 2-1/2 mile long sliver just 300 yards wide. The visit was a bit of a pilgrimage: my parents had honeymooned on the island in 1949.

Above the boulder-strewn shores, the trunks and limbs of madrona trees were rough with rust-red bark peeling back in curls to reveal a pea-green inner layer. A 50-yard-wide gap in the southwest side of Wallace opened to a well-protected cove elongated parallel to the island’s axis. I tied GAMINE at the dock and introduced myself to the young couple serving as caretakers. When I told them about my parents’ visit to the island they walked me to the cabin that was customarily rented to honeymooners. It was surrounded by radiant orange calendula and pale purple mallow in bloom.

That night, under a dark moonless sky, I lay belly down on the dock and peered into the water. It was filled with pin-pricks of cool blue light in pulsating rings—thimble-sized jellyfish invisible but for their bioluminescent fringes.

Bergie, the youngest of the crew aboard the yawl SVENSK, asked me why I was cruising in such a small boat. Three decades later I heard from him; he had taken to cruising small boats and answered his own question.

At the end of my first week I arrived in Nanaimo. The harbor at Newcastle Island was crowded with cabin cruisers and sailboats and the only small boats around were either stuck like limpets to the transoms of cruisers or propelled by small outboard motors that sounded like long-winded Bronx cheers. I docked next to a sleek yawl that hailed from Washington’s Bainbridge Island and from its rail two small boys and their parents watched me fuss with my gear as I answered their questions. The father translated for his youngest boy, Bergie:

“This man has come just as far as we have and he’s rowed all that way in that little boat.”

“Why?” Bergie asked, his eyes fixed upon me. I was suddenly mute. Bergie’s mother, sensing the awkward silence, filled in the blank:

“Oh, Bergie, he’s doing it because he enjoys it.” Enjoyment hadn’t immediately come to my mind. I thought of the bits of tape I had to wrap around the pads of my fingers every morning to protect them from the sting of holding the oars, and of my new habit of easing myself onto the rowing thwart, as if I were lowering myself into a tub of painfully hot water, to bring on the itch and tingle of salt-pickled skin by tolerable degrees. I thought of charred potatoes.

The next morning the yawl and I left the harbor at the same time. Bergie was wrapped in his mother’s arms as his father raised the spinnaker to catch the northwest wind for the voyage home. Driving in the opposite direction, to windward, GAMINE spat froth as she bit into the waves on the edge of the Strait of Georgia. I rowed with the hiss of the cold wind raking my ears and hearing the echo of “Why?”

The northwesterly brought clear, cool air and the foothills of British Columbia mainland and crests of the Coast Range, dappled white with glaciers and snowfields, appeared deceptively close, just perched on the horizon, despite the 20-mile breadth of the Strait. I turned east to make the crossing.

I set a course for Smuggler Cove, as far north as I could point on the mainland on a single port tack. I had the main, jib, and flying jib set and made good speed. The strait was lumpy but not choppy so I didn’t take a lot of spray over the bow. It was good sailing but after a while it became wearing. I was stuck at the helm, keeping my weight to windward and stretching to reach the tiller hour after hour. I finished the crossing with daylight to spare, but I was exhausted.

I slipped through the 25-yard wide, rock-strewn entrance to Smuggler Cove and rowed a few hundred yards south among the score of larger boats already anchored there. They all had stern lines to shore to keep them from swinging at anchor, so I had to pull ashore to set up one for GAMINE. I grabbed the tortured coil of polypropylene rope and tried to back an end through the mess enough times to tease out a length long enough to be of use. A woman on a cabin cruiser had been watching me with her binoculars and my exhaustion and frustration must have been evident. She rowed her tender over and invited me to join her and her husband for a bowl of hot chowder. I followed her, and tied up GAMINE alongside. The chowder was excellent and the use of their boat’s bridge for the night’s accommodation was just what I needed.

Al and Ada Priest

Al and Ada PriestI stopped in Madeira to visit some lifelong friends from my home town, but reluctant to miss the good sailing breeze that day, I stopped only briefly. About my green sails: I had taken Peter Culler’s advice to sew my sails of cotton boat drill and treat them with Cuprinol, a copper-based preservative. I never liked the color. It made my sails look like I’d cut them from old canvas tarps.

The wind shifted overnight and when I left Smuggler Cove I had a southwesterly in my favor. I headed up the mainland coast on a broad reach, making a brief stop in Madeira Park, and when I got back out on the open water of the Strait of Georgia, the wind was out of the southeast and strengthening. With the boom crutch serving as a whisker pole to spread the jib wide, GAMINE ran briskly, wing on wing. Waves were beginning to crest and, as they lifted the stern, GAMINE shot forward, plowing up two curls of green water that rose amidships and fell away in hissing white froth.

Log booms made the cove at Stillwater an especially quiet anchorage. On the north side of the cove is a hydro power plant built in the 1920s. The tall structure above it is a surge tower that regulates the water pressure in the 1-1/2-mile-long pipeline from Lois Lake to the power plant.

At Stillwater I tucked into a quiet cove that was crowded with rafts of logs waiting to be towed to sawmills. The shore was rocky and steep-sided so I tied GAMINE alongside one of the log booms, securing the bow and stern lines to the rusty cables binding the bark-bare logs together. I set up my kitchen and began cooking a piece of salmon given to me by my hosts at Smuggler Cove. There was enough to feed four, but I had no trouble downing it all.

My stay at Stillwater was how I’d imagined I’d spend my evenings—good food, a little music—but the steel strings on the guitar rusted and I rarely had time to play it.

I spent the night in the boat, slept well, and woke to a flat calm. I left the mast up, hoping I’d find a breeze, and headed out under oars at 6:30. I rowed along the coast for about 20 miles before heading west across the top of the Strait of Georgia. The air was still and stifling, the sunlight stinging on my bare shoulders and back. My hands, fortunately, had finally toughened up and the once-tender skin was now hardened with calluses.

The Straight of Georgia flattened for the afternoon that I crossed from the mainland to Mitlenatch Island.

I had rowed the four-mile length of Savary Island when a breeze filled in from the south, dappling the strait with dark cat’s paws of wind-scratched water. I set sail and headed toward Mitlenatch Island, some five miles distant, a dingy grey smear on a horizon between a sparkling sea and a luminous bank of cumulus clouds. The wind came around behind GAMINE and I eased the sheets and let her run. As she caught up with the wind, the air around me grew oppressively hot.

I left the mainland at 6:30 and rowed in a flat calm for 8 1/2 hours, covering 26 miles before the wind piped up and let me sail the remaining 5 miles to Mitlenatch Island.

Mitlenatch is a First Nations—Coast Salish—word meaning “calm water,” an appropriate name, as the island is where the tides wrapping around the ends of Vancouver Island meet without creating any currents. The water just rises and falls. North of Mitlenatch the ebbs, not the floods would be in my favor. Another native name for the island is Mahkweelayla: “The closer you get the farther away it appears.” It seemed that way to me in my long crossing to it.

The only company I had on Mitlenatch, aside from the birds, seals and sea lions, was an ornithologist who was doing research on ravens, or, as he put it, “plumbing the depths of the corvine brain.”

After spending the night at anchor, I left Mitlenatch at 5 a.m. Even at that early hour it was too rough for rowing, but I was eager to reach Campbell River, a town on Vancouver Island, to resupply. Gamine shook and rattled as she bulled into the waves and white fans of spray shot out from the rails. Every drop into a deep trough brought me to a stop. With the oars clawing at the water, I could feel the sluggishness of 600 lbs of boat and cargo. In my left hand there was a gritty sensation of my palm delaminating, epidermis sliding over dermis as if there were a layer of sand between them.

I set my course a bit off the wind to ease the pitching into the troughs, but the diagonal approach just made the dory roll too. As I tired, I found it difficult to sit upright and the gyrations of the boat worked my spine like a whip, snapping my head in all directions. The roll of the gunwales pried the blades of the oars from the water in the middle of the stroke and drove the handles into my kneecaps on the recovery. I screamed at the boat: “Move, dammit!”

After four hours making that miserable eight-mile crossing, I reached Willow Point, where I pulled the dory on to a malodorous mud flat. The anger I had felt on the water turned to shame. My fight against the weather had been an even match, but while I had been at my limit, the weather was only mildly foul. I was lucky that making myself miserable was the worst that had happened to me.

For the next six hours the tide would be in flood, and the current against me, but I was eager to get to Campbell River in time to buy supplies and get out of town well before dark. I got aboard and rowed close to shore, taking advantage of the back eddies as I worked my way north.

Seymour Narrows can be a dangerous spot for any boat the the current is at its peak. I came through in the early stages of the ebb and was eased into the north end of Discovery Passage.

After my shopping expedition, I rowed six miles on an ebb that swirled around Race Point and accelerated GAMINE through Seymour Narrows, a 3-mile-long, 1/3 mile-wide bottleneck where currents can reach 15 knots. Though I was tired and my hands still burned from the morning row, I was drawn into the narrow corridor between steep cedared slopes. It was the Inside Passage as I had imagined it: long avenues of water where the tides ran like shuttles beneath the stone and snow architecture of the mountains. The sun lingered above the crest of the ridge to the west and its amber light set GAMINE’s cedar planking aglow.

At dusk I pulled into Elk Bay, well shy of Chatham Point at the north end of Discovery Channel, and secured the dory alongside a log boom on the south end of the bay. As I was crawling into my sleeping bag a cruise ship passed by, a silhouette perforated with rows of bright portholes. I pictured myself on the other side of one of the portholes looking across the water toward GAMINE. Even in daylight, the dory would be too small to be noticed. For the first time on this voyage I felt lonely. Long after the ship had passed, its wake rolled gently beneath the boat and hissed along the gravel beach.

Just after midnight, I was shaken out of sleep by the pounding of GAMINE against the log boom. A cold northerly had furrowed the south side of the bay and I had to move to the north side to get into the new lee. Without getting entirely out of the sleeping bag I let slip the loops of line that held the dory to the logs and positioned myself on the thwart to row. As soon as I got GAMINE moving, luminescent spray from the bow shot out like tracers and spotted the waves with pale glowing bull’s-eyes. The wake was a path of light above the curved silhouette of the transom.

It was too dark to see how close I was to north shore; I rowed until I heard the squeak of salt grass against the hull at the north edge of the bay. Letting the boat drift, I sounded with the anchor until I had two fathoms under the hull, enough to keep me afloat until the alarm clock would rouse me to relocate before the morning low tide.

Having slept through my alarm, I was stranded on the tide flats. Here I’ve dragged GAMINE to the water’s edge and she rests at the far left. I’m standing where I was stranded, gathering gear to shuttle across the mud until it was all back aboard.

At dawn the boat was quite still and I felt well rested, but when I rolled over to catch a bit more sleep before the alarm sounded, the boat didn’t rock. I sat up and looked over the rail. The water was 70 yards away and GAMINE was firmly planted in the middle of an oyster bed. I glanced at the clock and saw that the alarm had been shut off. I must have hit it and fallen back asleep.

I set the floorboards across the mud and the sharp-edged oyster shells and piled my gear upon them. With the boat empty, I lifted the bow and the hull rose from the mud with a sound like the last of a milkshake sucked up a straw. With the painter tied in a harness around my shoulders, I leaned forward in the shin-deep mud and headed for the still-receding water. On eel grass GAMINE slipped along nicely, but on oysters she moved slowly, leaving a trail speckled white with bottom paint and crushed shells.

Getting the boat to the water was the easy part. The tide was still falling and I raced back and forth ferrying gear. With every load I dropped into the boat, I had to move it back out to get it afloat once again. A dozen sprints back and forth across the flats got everything aboard and left my legs bloodied and muddy. Sweat trickled down my face as I began rowing the 3-1/2 miles to Chatham Point.

The tide had turned and the west-flowing flood in Johnstone Strait was working against a stiff easterly. Waves were coming from all directions and crossing, making pointy crests like rasp teeth. I wasn’t able to make much progress rowing so I retreated to small cove west of Chatham to wait for a break in the conditions.

Figuring that I’d be stuck for hours, I threw a handline over the side to try my luck at fishing. After a half hour or so had passed, I heard an odd hollow, almost metallic whooshing sound behind me and turned around to see what appeared to be a length of black plastic pipe, slowly rising and falling in the water. I guessed the noise was the rush of air in and out of a steel tank submerged beneath the pipe. Whatever it was, it seemed to be drifting with the current as it was quickly closing in on me. I pulled the fishing line in and took a few strokes to get out of the way. It disappeared beneath the waves and when it surfaced it was just 20 yards from me. It suddenly veered and what I thought was a pipe broadened into the tall black scimitar of an orca’s dorsal fin. I grabbed my camera and searched through the viewfinder for the whales next rising, and a mere boat-length away I saw a slick, black dome breaking the surface and approaching the boat. An electric surge of adrenalin rushed up from my core and made my scalp tingle. I snapped the shutter and lowered the camera into my lap to face whatever was going to happen to me. I stared unblinking at the black shape, now only 5’ away, and noticed it didn’t have a blowhole. It had treads and whitewalls. People say their encounters with whales are profound, even life changing. It might have been that way for me if I’d been able to distinguish mine from drifting through an aquatic junk yard.

After my “close encounter,” with this orca, its dorsal fin visible in the center, touching the horizon, left me and headed west along Johnstone Strait.

At the peak of the flood, the current raced by the point I’d taken refuge behind at about seven knots. A line of a dozen seagulls rode it as disinterestedly as people borne by an airport’s moving walkway while GAMINE’s hull resonated with the sound of rocks tumbling past underwater.

Trapped by an adverse flood tide, I took refuge among the kelp in a quiet cove as seagulls raced by riding the current.

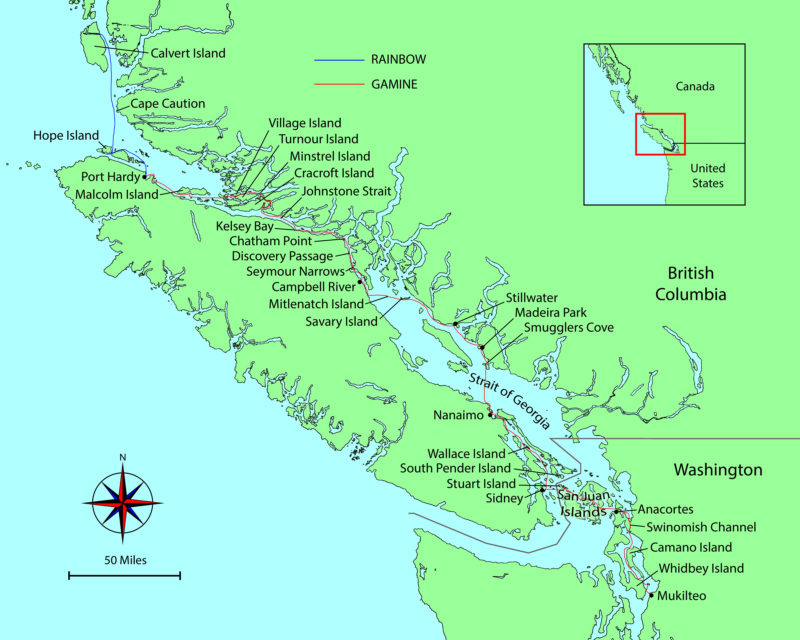

When the tide turned in my favor, I worked my way west along Johnstone Strait to Kelsey Bay. I left GAMINE in the harbor, ran a mile and a half along a dirt road to a grocery store, and hitched a ride back with a bag full of food. Another boat, the 72′ RAINBOW, arrived in the marina and docked near GAMINE. The skipper, Wayne, told me she was built as a racing 12-Meter and retired as a training vessel, re-rigged as a ketch. He and his complement of Sea Scouts were soon on their way again, sailing north along the Inside Passage headed for the Queen Charlotte Islands.

RAINBOW left Kelsey Bay ahead of me and I expected I’d never see her again.

I was eager to get to smaller, tamer channels and crossed Johnstone bound for Port Harvey, the bay between East and West Cracroft Islands. My chart showed a narrow passage between them that would lead to the cluster of small islands in the Broughten Archipelago. I rowed to the north side of Johnstone and there I was overtaken by a tug pulling a log raft that carried an enclosure made of poles and plywood. As the raft went by, I saw a big brown bull inside the enclosure. The tug was headed for Port Harvey, so I raced to the raft and tucked into its broad churning wake. As I had hoped, the water trailing the ends of the logs was creating a back eddy; I set GAMINE’s bow on one of the logs and the backwash held it there.

The bull this raft was carrying was making the rounds doing doing stud service at settlements scattered along the Inside Passage.

When we reached Port Harvey, the tug came to a stop and I rowed to the notch separating the forested hills of the Cracrofts. I found no passage there, and the brush growing in the valley made it clear that if there was once a waterway there, the land is now above the reach of the tides. So much for the 2-1/2-mile free ride. I had to row out of Port Harvey then round East Cracroft to get to Minstral Island. I arrived at 10 p.m., exhausted, and yet I was underway again at 5:30 a.m.

The weather was fair and calm when the sun rose, so I got an early start leaving Mistral Island.

The settlement on Turnour Island was unoccupied, but many of the buildings remained standing amid the encroaching underbrush.

At Mamalilikulla, the settlement on Village Island, this totem pole was standing and beauty of its carvings was undiminished by age and weather.

The smaller waterways west of Minstral did offer easier going, but I was tired and finding it increasingly difficult to stay at the oars. I made brief stops at unoccupied native villages on Turnour and Village islands and called it a day at Swanson Island after rowing about 20 miles. After a two-hour struggle with the polypropylene rope clothesline system, I managed to get GAMINE set at anchor.

GAMINE rested placidly in a Swanson Island cove, but I was feeling the strain of the travel and not feeling so peaceful.

Sleeping ashore turned out to be a mistake as the mosquitoes found me at sundown. I pulled the bivibag over my head and managed to fall asleep. In the middle of the night I woke up and felt myself rocking. I peeked out and saw water all around me. I starred intently at the flood surrounding me and I couldn’t understand what was happening. I reached out to touch the water and what I felt was not water but grass. The hallucination disturbed me, but I was too tired to stay awake.

When I woke in the morning, I was hemmed in by fog. GAMINE had been set on the rocks by the falling tide. I decided to head home. I’d had enough.

When I left Swanson Island I made crossings only when I could see the island I was heading for.

I left Swanson hopping from island to island when the fog lifted enough for me to make out the next landfall. On Malcolm Island I stopped in the village of Sointula and stocked up on food and fresh water. I called home and talked to my parents before heading back to the boat to spend a quiet night sleeping under a rack draped with drying gill nets.

Port Hardy was home to a large fishing fleet. I was considering bringing an end to my voyage here, but chance encounters led to continuing.

The 25-mile row from Malcolm Island to Part Hardy was my first experience rowing in ocean swells. The gentle rise and fall was a pleasant sensation and a welcome break from the battle against wind-driven chop.

In Port Hardy I was still uncertain about whether I would continue north. Whatever I decided to do, I’d need more money so I called my parents to arrange a wire transfer. I visited the town’s hardware store and while I was browsing I overheard a man asking the clerk for the Evergreen Cruising Guide, the book of charts I’d been using. When the clerk was attending to another customer, I whispered to the man: “Wanna buy a used Guide?” He and I then left the store together. His name was Don; I rowed him in GAMINE to his boat. Instead of taking cash for the guide I took Don’s charts for the B.C. waters to the north of Port Hardy. The deal tipped the balance toward continuing my voyage north. When we were rowing through the harbor, Don had pointed to RAINBOW, so when I left him, I rowed alongside her. Wayne recognized me and invited me aboard for dinner.

I had lightened the skiff by putting a lot of my gear aboard the ketch and leaving some of GAMINE’s in the stern to keep her bow riding high under tow.

Wayne and I spent the following day wandering Port Hardy. He asked me about my plans and I said I was considering continuing north, though I was worried about rounding Cape Caution, a rare stretch of the Inside Passage that is fully exposed to the Pacific Ocean. Wayne invited me to come along aboard RAINBOW to the Queen Charlotte Islands. I jumped at the opportunity.

I was worried about GAMINE towing well pulled by her bow eye, so I made a bridle for her that was anchored to the tholes and risers and pulled tight to hold the towline low on the stem. That kept her bow riding high.

GAMINE was in tow, skipping wildly at the end of her tether as RAINBOW sailed out into Queen Charlotte Sound. The beat to windward was into a steep 10’ swell that pitched the 72-footer and churned the crew’s stomachs. The skipper, the first mate, and I took turns at the helm while some of the scouts, who can be forgiven for their ignorance of naval etiquette, one after another hung their heads over the windward rail and painted the white topsides with their breakfast. The first mate set a proper example by losing his meal to leeward.

I took shifts at the helm as RAINBOW charged through 10′ swells.

With RAINBOW exceeding 10 knots, GAMINE leapt over the wind waves but survived the crossing of Queen Charlotte Strait.

The strong wind tore RAINBOW’s mainsail and bowed her forestay.

We raced along at a steady 11 knots as RAINBOW’s bow dove into waves sending green water 6′ up into the genoa. The peak of the main developed a tear that quickly worked its way from leech to luff. Wayne made the decision to bear away from the Queen Charlottes and head northeast into the shelter of the Inside Passage. We anchored in the right-angle intersection of two half-mile wide channels separating Calvert Island from Hecate Island.

With the rough passage across Queen Charlotte Sound and past Cape Caution behind us, RAINBOW reached a calm refuge at Calvert Island.

It took the rest of the day and most of the next for the crew to repair the mainsail. The lost time meant they’d have to turn away from the Charlottes and return to Victoria, RAINBOW’s home port. That night I reloaded the dory and at twilight got back aboard and said goodbye to the crew as RAINBOW set out under power to take advantage of the midnight calm.

With RAINBOW gone and the stars masked by a black veil of clouds, the emptiness of the darkness and silence surrounded me. I looked over the side of the boat hoping to see the bright constellations of bioluminescence, but the water was invisibly dark. I aimed my flashlight over the side and its beam fell upon countless large yellow polka dots. The boat was surrounded by jellyfish that looked like yolks and whites spilled from eggs as big as basketballs. As far as the beam of my flashlight could reach, the bay was cobblestoned with their undulating domes. Afloat on the unstirred makings of an immense omelet, I settled into my sleeping bag, cradled on a living sea.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly. Part 2 of this month-long, 700-mile voyage will appear in the November issue. Parts of this story were first presented in the August 1987 issue of Shavings, an annual publication of The Center for Wooden Boats.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Great adventure! Well done!

Cheers, Robert

A beautifully written piece about a genuine adventure.

Chris,

After reading your ’80s trip in GAMINE up the Northwest Coast, I better understand why you are the editor of Small Boats Monthly. Your boat GAMINE blew me away—a 2-part mast and never-ending sails. You actually took the trip that we all wish we would have taken when we were young but didn’t. Although I have to admit, after the encounter with the orca, my boat would have been full, but not with water. Your deadpan but highly illustrative writing kept me glued and I anxiously await Part 2!

Regards,

Pat

Crazy story, told well. GAMINE was very patient with you 🙂

Cheers

Kent

A grand tale. How did you keep the camera working? Keen to read the next installment.

Peter in Redmond

Thanks, Peter. My camera at the time was a Konica Autoreflex T, a 35mm SLR that I bought used from a classmate at my high school around 1968. It had a built-in exposure meter that was visible in the viewfinder; everything else was manual. I used the same camera for a 4-month canoe trip from Quebec to Florida, a 2 1/2-month row from Pittsburgh to Florida, and finally in 1986 for my 2-month second Inside Passage trip. I kept it in waterproof bags and boxes, usually with some silica gel to absorb moisture. I’d also have a small towel handy to dry my hands before using the camera. The camera put up with a lot of hard use and never required any maintenance.

After my first Inside Passage trip, I bought a radio-controlled shutter release accessory that allowed me to “selfies” from up to 400′ away. That was much better than being limited to the camera’s built-in 10-second timer.

Chris, thanks for the story. Sailing the Inside Passage for your first “overnight cruise” is an ambitious undertaking!

Tom

After completing second half of the Inside Passage in 2017, I can attest to how much has changed on land since your first trip. The totem at Mamillilkula has long since fallen over and has mostly rotted away, the Minstrel Island marina has long since closed and the fishing fleet at Port Hardy is a mere shadow of its former self, among other smaller changes. Notwithstanding all that, the sea is still the sea and it’s still a great trip in a small engineless boat.

I have just finished reading your article and following it on a map of Vancouver Island. My wife and I spent a week each on Cortes and then Quadra Island this summer, so your route was doubly interesting.

How adventurous you were then (and possibly now as well!)

I look foward to the next installment.

Around 1997 or so five of us drove to Prince Rupert, rode the ferry over to Skidegate on Graham Island (Queen Charlottes, aka Haida Gwai) and hired a big Zodiac down to Raspberry Cove (which has no raspberries nor its it a cove), to commence a kayak trip back north to Moresby Camp. We were in one small cove (can’t remember whether we camped there) where we saw the same sunny-side-up jelly fish. What puzzled me was how hundreds of them found their way to that very cove. Suspect it had something to do with procreation, or other kind of recreation.