If yours is a small professional shop, one with a self developed specialty product, and that product is a humble skiff—a wooden, outboard-powered utility skiff, to be precise—then you’ll have to launch a lot of boats, successful boats, before that singular product acquires a regional reputation. In time, the boat may take on your name. With luck, and the publicity conferred by print publishing, the boat may transcend the geography of its origins and assume an identity known nationally; in effect, it may achieve brand recognition.

Alton Wallace’s West Pointer is one such craft. The Tolman skiff is another. Since 1973, Renn Tolman has been refining an all-purpose, typically open workboat generically referred to as an Alaskan skiff.

I’ve been a student of Alaskan skiffs for about as long as Tolman has. But where my interest was remote—from the opposite corner of the country (Maine)—Tolman pursued his on location, having settled in Homer, Alaska, in 1971 after a teaching career in Rhode Island. He brought with him woodworking skills, a passion for long-range fishing and hunting in boats of his own making, and what became a constant quest for the perfect skiff for Alaska’s coastal waters. Not least, he retained an ability to teach—except now the subject is skiffs rather than American history. Today, Renn Tolman has not only put his name on an Alaskan skiff, he’s probably defined it.

Photo by Philip Walker

Photo by Philip WalkerRenn Tolman designed his eponymous skiff as a workhorse for rugged Alaskan environs. The boat has proven to be adaptable to a wide range of locales—and to a wide range of configurations. AGLOOKIK, was built by Philip Walker for use around the North Wales island of Anglesey —“a wild and beautiful place,” says Philip.

I’ll do the design history in brief. Once in Alaska, Tolman started with a traditional tombstone-stern dory fitted with an inboard motorwell. It was the slowest boat on the bay, but he liked its looks, and appreciated the sea-worthiness of its sweeping sheer, flared sides, and ability to carry loads. So he switched to so-called dory skiffs: first a Carolina, and then a local type, the Cook Inlet, and then a Carolina crossed with an Oregon Dory. The latter were faster boats, but they were flat-bottomed and thus a hard ride in any but calm conditions.

It wasn’t just design, though, driving Tolman and his partner, Mary Griswold (the pair turned professional within 10 years of arrival in the state); it was also materials and construction. They adopted filled-epoxy adhesive and epoxy resin–impregnated fiberglass cloth fairly early. The big breakthroughs came when they changed to longitudinal framing (as practiced by veteran Homer builder George Hamm), and combined it with then-new stitch-and-glue construction. Tolman’s overall system—specifically: a few sturdy stringers and a minimum of athwartship structure; stitched-and-glued plywood panels; epoxy saturation and fiberglass sheathing—enabled Tolman and Griswold to produce durable skiffs competitively. Equally important, it made possible an economically built V-bottomed hull form, which vastly improved the ride quality.

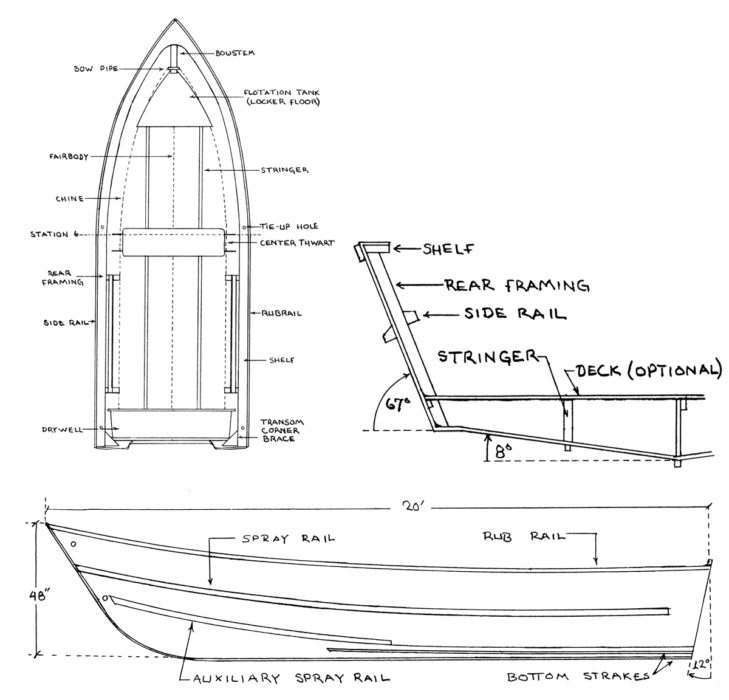

Within another 10 years Tolman had standardized on a customizable design he’d devised through considerable trial and error, and produced in two lengths: 18′ and 20′. Both sizes share the same hull; the 18 is simply a 20 with 2′ removed in the afterbody. This boat, the quintessential Tolman skiff, is characterized by a shallow V-bottom (8 degrees deadrise at the transom), flared topsides, high bow, strong sheer, and full-length spray rail. Lightweight and easily driven, a Tolman hull can be fitted out in a great variety of configurations—set up for beach cruising, say, with tiller steering. It can be rigged with center-console controls, or configured for recreational or commercial fishing (removable binboards, and net-hauling gear with net-kindly gunwales), or perhaps be given a small cuddy.

Photo by Mark Abb

Photo by Mark AbbMark Abb of Camden, Maine, built this center-console model.

Some 20 years on, Tolman had built enough of these boats to write a book about them, A Skiff for All Seasons: How to Build an Alaskan Skiff, published in 1993. I reviewed it in WoodenBoat magazine that year (No. 113), recommending both the book and the boat—but challenged Tolman’s claim that an amateur could complete one of his skiffs in the 300 hours predicted. Well, shortly after that issue of the magazine appeared, a letter arrived from Chris Banas, an industrial-arts teacher and first-time backyard boatbuilder in Kenai, Alaska, who’d built the 20′ hull in 300 hours, “plus 50 hours for extras, 350 hours total. Those are after-work hours—a notoriously inefficient type of hour,” Banas wrote. He enclosed a photo of the finished product, at wide-open throttle, with family aboard—minus Banas himself. “I needed a skiff that was light enough for my wife and kids to handle on and off our beach, yet stout enough to handle a day in our water-taxi business, which involves remote-site drop-off and pickup. This skiff is it. We couldn’t be happier with her. The fact that repairs and modifications can be made in the field is an additional bonus in our situation.”

And not long after Banas’s letter, Mark Abb, former shop manager at WoodenBoat School, started a 20′ Tolman skiff on speculation, at a rented shop in Brooklin, Maine. Abb corresponded with Renn Tolman on certain construction details; Tolman connected him with Banas. Abb had prior boatbuilding experience, though not in stitch-and-glue. “I used fir plywood, but won’t do that again,” he recalls. “Turned out fine, but was an effort to sand and finish well.” Tolman also connected Abb with a buyer, once the project was well along. According to Abb, who sea-trialed the skiff before delivering it, Renn Tolman “designed a solid-riding, dry, no-frills skiff with a capable appearance to match. I was pleased with the stiff bottom; full-length stringers allowed no oilcanning [deflection of the bottom panels].”

Abb continues: “I liked the versatility for building the boat’s interior, and may have ‘corrupted’ things as a result. But the last report from her owner—a Nantucket [Massachusetts] fly fisherman—was thumbs up. He re-powered with a Honda 90-hp four-stroke [Abb had installed a 70-hp two-stroke] and said it goes. I never heard if the extra engine weight was an issue.

“All in all, a straightforward project that yields a great boat within reach of those with limited experience. Mine took more time than described, but that was a result of building on spec to my own wants, and then working to suit the buyer. Regardless, I’m glad with the way it turned out, and have no reservations about building another.”

Photo by Jim Shula

Photo by Jim ShulaJim Shula of Buxton, Maine, built this Tolman Skiff for use as a trailerable camp cruiser.

In 2003, Renn Tolman wrote a second book, Tolman Alaskan Skiffs: Building Plans for Three Plywood/Epoxy Skiffs. And, he secured the publishing rights to his first volume, which had gone out of print. Note that Tolman’s name is not only on the cover of the new book as author, it’s now also on the boat. And the new book’s format is larger, since the readability of his drawings was a point I’d addressed in my WoodenBoat review of book one. More to the point, the Tolman skiff has evolved, along with— and in part, because of—the technology that powers it.

Tolman’s 20′ model is the new “Standard.” A lengthened version (21′ 4″ ) with wide chine-flats, introduced in 1993, constitutes a second model called the “Widebody.” The third and latest skiff model is the “Jumbo”; it’s 22′ in length, with a deeper-V (12 degrees deadrise at the transom) and additional draft and beam. A new feature for these boats: all sorts of optional superstructure, particularly for the Widebody and Jumbo skiffs. Jake Berry, a builder in Sedgwick, Maine, just completed a Tolman cabin skiff for a customer in, of all places, Alaska.

Two significant things have not changed since Tolman’s first book: the basic design and construction of a Tolman skiff; and the extraordinary amount of clear, concise, practical information Tolman provides the builder—amateur, semiprofessional, and professional alike. His books are arguably the most comprehensive treatment of a single family of small-craft designs in the technical literature of boatbuilding. Having designed, built, repaired, and modified his self-styled Alaskan skiffs, exclusively, for several decades, there is hardly a detail of planning, construction, outfitting, rigging, operation, and maintenance that Renn Tolman hasn’t thought through, or been apprised of by one of his customers. And he explains all of it: how to build this or that part; what alterations to that part, if any, have been made over time, and why; and which of the many individual elements (storage and flotation compartments, demountable seats, assorted cockpit and splash-well arrangements, an ergonomic center console, cactus-shaped rod racks, etc.), offered up as measured drawings with related commentary, can be added, or not, to your boat.

Tolman’s discussion of four-stroke outboards—plus the increasingly common smaller auxiliary, or kicker— and their potentially deleterious effect on weight distribution is extremely thorough. He tells you exactly which engines (as of manufacturers’ model year 2003) are suitable for his transoms, and why. Tolman’s boats are, by definition, outboard powered, but he’s more honest about coming to terms with these new power plants than are many ’glass and aluminum boat manufacturers, who’ve been reluctant to incur the expense of revamping their production molds and jigs to accommodate four-strokes.

Tolman skiffs are built directly from the book Tolman Alaskan Skiffs, from which these drawings are taken. The book is a chapter-by-chapter instructional on hull construction and layout; numerous configurations for several hulls are offered.

While this essay of mine was not intended to be a book review, it’s virtually impossible now to separate a Tolman skiff from the all-important text that describes how to build one, how to choose the one to build, how to customize that choice, what tools are needed, the shop space required, the list of materials, sources of supply, and the time it will take to complete each step of the building and finishing process. Tolman Alaskan Skiffs is available from the WoodenBoat Store. A Skiff for All Seasons can be ordered from Kamishak Publishing (Homer), while supplies last. As Tolman says, “All the important information in the first book is included in the second, but you may find the former more entertaining reading, and there are some different photographs.”

Final testimonial: Tom Beaudoin, a boatbuilder pal from way back, was drawn to the Homer area from Maine years ago, as a base for hunting and fishing, much as Renn Tolman was. The two became friends. When Tolman and Griswold upgraded to a new 20-footer from an 18-footer they’d logged thousands of distant-bay and tidal-river miles in, Tom Beaudoin bought their well-worn 18.

Happy is he who owns Tolman’s own skiff.

Renn Tolman’s book Tolman Alaskan Skiffs is available from the WoodenBoat Store, P.O. Box 78, Brooklin, ME 04616.It includes plans and detailed building instructions for three different models of this boat.

Aglookik – oh, I was hoping to see more photos of her – the cubby and controls etc.

Great article on a series of vessels I’ve been considering to build for some time. However my question is…from the book, can one build a 20′ wide-bodied Tolman skiff with the deadrise of 12 degrees at the transom? 20′ is the maximum I can handle in my shop and waters around my home city can be extremely choppy.

Glad you liked the article — published (not posted) 15 years ago. Here’s an update. Four-stroke gas outboards remain considerably heavier than equivalent two-strokes, and now dominate much of the marine-power market. Several boatbuilders offer pre-cut kits for Tolman skiffs, a sign of their growing popularity. The May/June 2021 issue (No. 280) of WoodenBoat magazine features an excellent article by veteran designer-builder John Marples titled “Building a Tolman Wide-Body Skiff: Part 1”; in it he presents a number of construction tips and techniques augmenting those found in Renn Tolman’s comprehensive second book, Tolman Alaskan Skiffs, which is still in print (and available from The WoodenBoat Store. Significantly, Marples says in his introduction: “I cannot stress enough that before buying materials or doing any cutting, prospective builders should read the entire book to get the overall idea of how things go together before deciding which model to build and which options to include.” And finally, you may have choppy waters where you live, Rob Webber, but Tolman regularly took his skiffs through rough seas along the complex coast of Alaska. If Renn, who died at age 80 in 2014, thought the Widebody model needed more deadrise angle than the 8° specified, he’d have drawn it. The 12° angle you mention amounts to a change in hullform, not the boat’s outfit or layout; in the book he addresses why only the Jumbo model merits a deeper V-bottom.

Thanks very much, Paul, for your reply.

I built a 24′ Jumbo with pilot house and cuddy cabin. Launched her in August of 2019 on the New Meadows River (Maine). The TAKU (named after a glacier in Alaska) is powered by a 115hp 4-stroke Yamaha. Plenty of power and great fuel economy.

The starting point was when my two younger brothers built a center-console Standard skiff almost 30 years ago. This past winter one of the brothers got the itch to built another. This time a Widebody. A three Tolman family!

Needless to say, hull two and three never would have been built if we did not know how seaworthy Tolmans are and how easy they are to construct.

On the Jumbo, do they provide plan options to reduce the size of your pilot house? Reduction of the last widow panel (give or take?