The Boothbay Harbor One-Design is a particularly handsome boat that has proven itself in the choppy waters off Boothbay and Pemaquid, Maine. It’s an easy boat to sail, while being both maneuverable and fast, and its design is the product of some of the best boat minds of the 1930s.

Shortly after the J-boat RAINBOW successfully defended the AMERICA’s Cup in 1934, her designer, W. Starling Burgess, moved to mid-coast Maine and hired Geerd Hendel as his chief draftsman. Their primary work, funded by Alcoa and loosely overseen by Bath Iron Works, involved designing high-speed military craft made of aluminum. For recreation, both men focused on the emerging fleet of Boothbay Harbor daysailers, with which Hendel was already deeply involved. Starting with lightly built, plumb-ended centerboarders much like those that raced on lakes back in his native Germany, Hendel was in the process of converting four of them to keel boats when Burgess arrived. (As centerboarders, they had proven not to be up to salt water’s more boisterous conditions.) Hendel’s experimentation led to SANDERLING, built by Norman Hodgdon for the summer of 1936. She was the Boothbay Harbor One-Design precursor—and the first sizable boat Norman Hodgdon built.

Photo by Maynard Bray

Photo by Maynard BrayThe Geerd Hendel–designed Boothbay Harbor One-Design is a sporty and seaworthy short-ended daysailer-racer. It was designed in the mid-1930s, when limited overhangs and long waterlines were that region’s rage. Several designs of these basic proportions came out around the same time.

The mid-1930s were the bleak Depression years when small boats rather than big ones were receiving attention—quality attention—from Boothbay region designers, builders, and sailors. Boats with long waterlines and short overhangs began dominating the Boothbay racing fleet in those days, and top-echelon designers took notice. A long waterline means a faster boat; boats of these proportions came not only from Hendel and Burgess, but also from Charles Hodgdon of East Boothbay’s Hodgdon Bros. Yard, and from L. Francis Herreshoff.

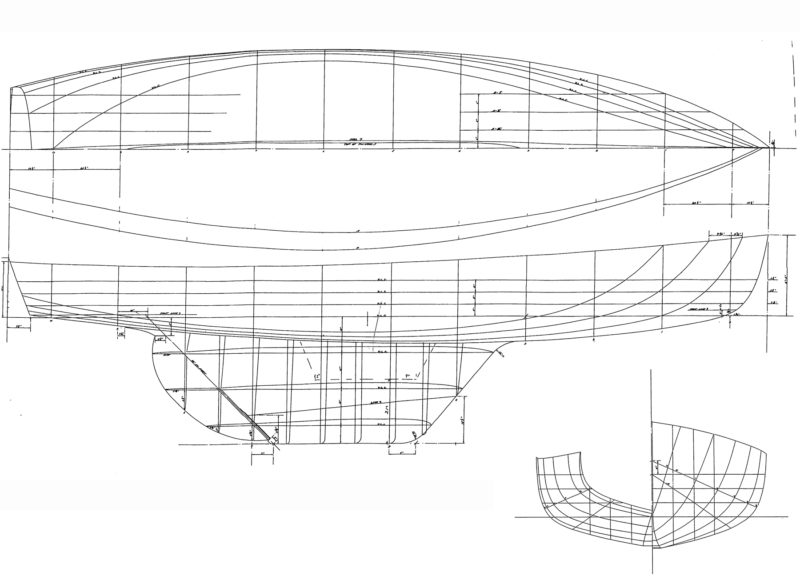

Hendel introduced a boat called LOON late in the 1937 season, and was then asked to work with the Boothbay Harbor Yacht Club, and particularly with its selection committee, in refining LOON’s plans to become a one-design class that would be cheap to build and fast to sail, and whose plans would be available to any builder—as these sailors intended to shop for the best price. The parameters echoed the fleet average of 21′ overall, about 19′ on the waterline, and carrying 200 sq ft of sail. After testing and massaging LOON, they agreed on what became known as the Boothbay Harbor One-Design (BHOD). It was an immediate hit, growing to 15 boats by its second season, 20 by the start of World War II, and 37 boats when wooden construction ended in 1966. (The final count came to 53, including the two subsequent batches of fiberglass boats.)

Geerd Hendel’s wooden BHODs were built upside down, then turned over and set atop their outside-ballasted fin keels—an efficient way to build any wooden boat whose design allows it. The BHODs’ flat transoms, as well, were an economy measure. The initial cost of these boats was in the neighborhood of $850.

The original planked construction of the BHODs has not held up especially well, as the boats have rather small frames and deep keels. However, the cost-cutting virtues of the original boats also make the BHOD an ideal candidate for the more robust and lower maintenance cold-molded construction. This technique involves the gluing together of multiple layers of diagonally laid veneer-like planking. It was this realization as well as a lifelong fondness for the BHODs that brought a kind of ad-hoc group together at Brooklin (Maine) Boat Yard, a long-standing leader in cold-molding. Besides designing and building new boats with cold-molded hulls, the yard had rejuvenated two aging BHODs belonging to Ted and Sandra Leonard—one of them nearly 20 years ago. Ted’s BLUE WITCH was detached from her fin and ballast, turned upside down, her hull sanded and faired to good wood, given a two-layer sheathing of 1⁄8″ diagonally laid veneers set in epoxy, faired and painted, then set upright again atop her original fin keel. Despite many seasons of sailing, her hull remains flawless and tight. Not surprisingly, Sandra’s boat, INDIA, received the same treatment a few years later.

Photo by Maynard Bray

Photo by Maynard BrayThe original plank-on-frame construction of the Boothbay Harbor One-Design did not stand the test of time. Two of these boats, BLUE WITCH and INDIA, owned by Ted and Sandra Leonard, received cold-molded overlays. Their hulls are much smoother than the dew-soaked topsides seen here suggest.

Based partly on this track record and partly on the yard’s expertise, Ted Leonard (who raced BHODs as a lad, as did his father) chose to sponsor a new BHOD of cold-molded construction. With input from Steve White (the yard’s owner), Bob Stephens (BBY ’s chief designer), and a little from Ted and me, the details were worked out and depicted on a new construction drawing by Bob. Instead of 1⁄2″ cedar planking, caulked, the new skin will consist of three layers glued together—the inner being 1⁄4″ thick running fore-and-aft over steam-bent frames, followed by two diagonally laid 1⁄8″ veneers running at right angles to each other.

As of this writing, finished drawings have been worked up and approved by the BHOD Association. The building jig has been completed, and over the winter the new hull will take shape. Ted’s goal is to share the information so that anyone can build one of these fine little daysailers using a method that has been proven. Finished boats will have strong and dimensionally stable skins, so you can store these BHODs in your garage or under a tarp with assurance that they’ll keep well and not leak when launched. The hulls will hold paint well because there’s no swelling and shrinking with changes in humidity—no seams to open, shed their paint, and ultimately leak. Fiberglass boats have some of these same advantages, but because that material isn’t self-fairing between supports the way wood is, fully faired and waxed female molds are necessary.

Since this boat weighs under 2,000 lbs, you’ll be able to tow it from place to place over the road behind the family sedan, expanding your sailing venue without damaging your boat. If the boat is equipped with a mast that swings in a tabernacle, stepping and unstepping should be a do-it-yourself operation.

Photo by Maynard Bray

Photo by Maynard BrayTed Leonard at the helm of BLUE WITCH. The success of this boat’s cold-molded overlay (it strengthened the hull enormously) has inspired the construction of a new BHOD, to be launched next summer. The new boat will have conventional steambent frames, like the originals, but will have a cold-molded, rather than planked, hull.

It’s a thrill to sail a BHOD, either singlehanded or with a friend or two. You tuck a cushion under your fanny and sprawl on the floorboards, where you’re out of the wind and much of the flying spray, yet you can see all around since your line of sight is under the boom and not obstructed by it or the mainsail. In tacking, the mainsail takes care of itself. Although the jib has to be let go and resheeted when changing tacks, it’s a small sail that blows across to the new lee side and sheets in easily once there—hardly needing the winch except in strong winds. With half her total weight at the bottom of her keel, the BHOD can be driven harder than a centerboarder of equal size. A reef is seldom needed and capsizing almost unheard of. Nevertheless, flotation chambers in the bow and stern will keep the boat from sinking should a catastrophic knockdown and swamping occur.

The resurgent interest in BHODs comes largely from a fleet roster developed by Association secretary Alden Reed—a listing that accounts for all 53 BHODs. Alden’s roots run as deep as his research in tracking down the boats. His grandfather Alden sponsored some of the early boats to get the class on its feet, and his father, Edgar, while a youngster, often crewed for Starling Burgess during the late 1930s.

If you do not plan to race, and are not constrained by the one-design parameters, the design invites such modifications as a reduced keel and separated rudder, curved transom, small cabin or boom tent, and tabernacle mast. The boats are small enough to store in the garage, yet big enough to give one the thrill of sailing fast—a perfect balance between manageability and performance.

There’s a newly chartered Boothbay Harbor One-Design Association, open to anyone interested in the boats. It organizes the racing, and publishes a comprehensive quarterly newsletter that covers restorations as well as recent race results. Ordering details for the new Boothbay Harbor One-Design Plans were being developed at the time of publication.

For a displacement hull, top speed is a function of waterline length. That’s the beauty of a Boothbay Harbor One-Design: The waterline length is nearly equal to the boat’s overall length. The short ends also reduce the boat’s tendency to pitch.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2007 and appears here as archival material. If you have more info about this boat, plan or design please let us know in the comment section.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

For what it’s worth here are some photos of Maynard Bray’s own (rebuilt) One Design OSPREY which is now back in the Boothbay Harbor YC fleet.

The only thing I’d wonder about is the status of the updated building jig Maynard mentions. It was, I’m thinking, used to build EIGHT BELLS at BBY some years ago. EIGHT BELLS is also now owned by a Blake family member here in Boothbay Harbor. I recall a rumor that the jig may not be available or abandoned or something. Maynard would surely know more.

Here’s EIGHT BELLS on launch day.

Finally, here’s a photo of my mother-in-law, Margaret Orne (Kelly) standing on the deck of one of Geerd Hendel’s precursors of the BHOD when she was voted Miss Boothbay Harbor in the 1930s. Another of the boats is on a mooring in the distance.

Hi,

I wonder that adults do not wear PFDs. Is this only something for children?

Ted Leonard died in October 2007. I don’t know if he saw/ sailed on the new BHOD he sponsored.

Hi Ben,

Ted did get to sail EIGHT BELLS, but only for part of her first season which, unfortunately, was his last. The building jig burnt up in the fire that leveled the facility where it was stored. Luckily, the BHOD Association, to whom Ted donated it, had it insured. That jig, after EIGHT BELLS, went briefly to the WoodenBoat School where instructor Eric Blake used it to build OSPREY which my late wife, Anne, and I sponsored, then sold to the Clarkson family.

Great article! The BHOD is a lovely looking boat. Glad to hear that there is a revival in this design and improvements on the construction. Thank you.

Maynard, thank you for this great article and so great to see an older photo of my BHOD, INDIA, which I purchased about five years ago. One thing I’ll note about the BHODs is that for those lucky enough to have a set of the sails with the original sail plans, the boat is incredibly balanced for daysailing (though the original sails are a bit smaller, especially in the leech – so not as quick for racing). I can be sailing close hauled with a 15 degree heel and the boat will sail itself. There is zero weather helm. I taught sailing for 10 years and have raced for 25 years on everything from dinghies through college, Tripp 40s, and numerous J-Boats and I have never experienced helm as light as that on a BHOD. Probably the easiest boat I’ve ever sailed.