Here’s a fine outboard skiff that will prove inexpensive, easy to build, and fast on the water.

Early on the finest Saturday morning in July, I found my way to a perfect small lake in central Maine. Hidden away in the green foothills, not twenty minutes from the blacktop parking lots and shopping mall bustle of Augusta, this secluded water offers a good home for Henry and Sam Whittemore’s Diablo skiff.

Sitting quietly at her mooring, BONITO, as the Whittemores call their boat, is striking. Designer Phil Bolger drew sweeping longitudinal curves into this skiff. These contrast with the hull’s sharp and angular transverse sections to make a strong visual statement. Either you will really like her looks (for the record, I do), or you won’t. She leaves little room for neutrality. The matter of her performance seems more certain: it is superb.

Photo by Henry Whittemore

Photo by Henry WhittemoreBONITO’s Diablo design is derived from the Amesbury skiff—itself a dory-derivative. The plywood hull is easily built, and easy on the eyes.

Henry and Sam, father and son, built this skiff a few years back when Sam was an eighth-grader. Now he’s a sturdy high-school senior, and I weigh close to 200 lbs. But as the two of us climb aboard, the Diablo easily sur- vives our weight at the rail. Sam fires up the 15-hp Johnson outboard, and we idle toward open water.

Free of the harbor, he advances the throttle. Acceleration is instant and hang-on-tight impressive. As the young skipper throws the tiller over hard, the skiff banks easily into an incredibly tight high-speed turn. She leans reassuringly toward the inside of the turn like a well-piloted aircraft. In the morning calm, we cut sharply back and forth across the photo boat’s wake. BONITO handles the manmade waves smoothly and with absolute control.

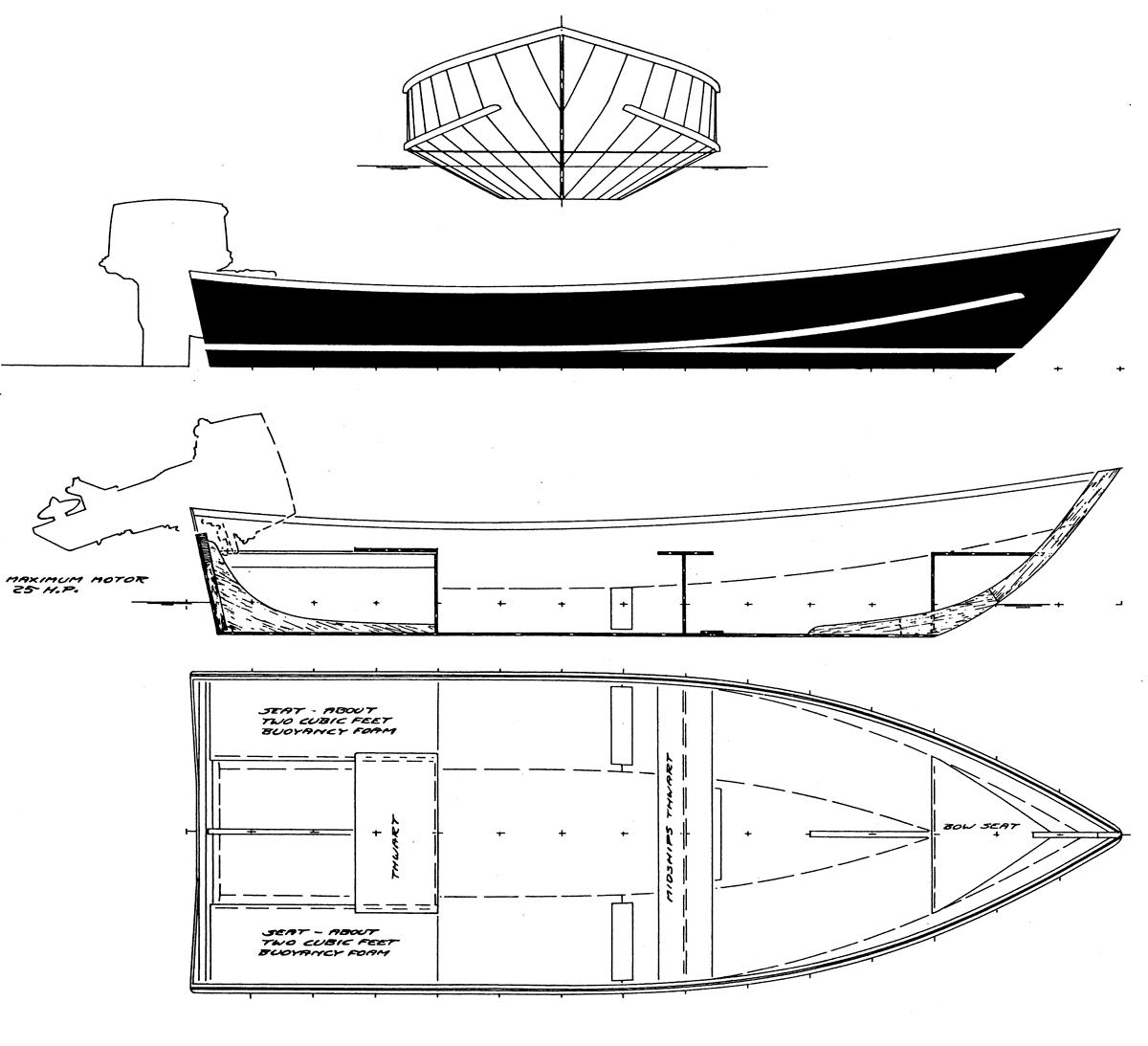

A quick look at the hull described by Diablo’s body plan reveals the reasons for her prowess. The narrow (2′- wide) bottom, combined with substantial bilge panels that rise at an angle of about 26 degrees, offers low wetted surface when the boat is lightly loaded or when she rises up to plane as we open the throttle. Those well-angled bilge panels also ensure that this skiff banks predictably toward the inside of high-speed turns. The panel to the outside of the turn offers plenty of lift. There seems little danger that we might trip over a chine and capsize outward.

Photo by Henry Whittemore

Photo by Henry WhittemoreAuthor O’Brien enjoys an outing with builder Sam Whittemore on a central Maine lake. The materials for this boat, BONITO, came from the local lumberyard.

When running at speed, Diablo shows considerable dynamic stability, but what about initial stability when she’s stopped dead in the water for fishing or working? Does that narrow bottom give cause for worry? Not really. She heels down some as we approach the rail, but then she stiffens firmly…and more quickly than we might have expected. Fishermen will like this friendly stability curve.

The hull’s straight bottom up forward mimics the Amesbury skiffs from which Diablo is derived, and its shape will help to ease construction. Bolger predicts: “It will stop her when it digs into the back face of a sea, but not intolerably since she has the exaggerated topside buoyancy to pick her up.”

After testing the Diablo prototype, builder Dynamite Payson praised the hull’s relatively full forward sections in Build the New Instant Boats (International Marine, 1984): “She can carry much more weight up there than a slim- mer craft of her size can, and with a following sea that’s pushing her along at a good clip, she won’t start to nose dive, either. Sure, going into heavy weather she is going to pound a little more, but…I can slow her down and wiggle my way over head seas….”

Photo by Henry Whittemore

Photo by Henry WhittemoreBONITO is easily nosed onto a beach, and takes the ground standing bolt upright.

Payson, a commercial waterman before he began putting together boats, holds powerful feelings about having adequate buoyancy forward: “This bias of mine has its roots in my experience with various types of lobsterboats I used while working off Metinic Island. During the late ’40s and early ’50s, a trend developed away from the lower-powered, easily driven fishing boats toward [hulls with broader sterns]. There was an awkward time during that evolutionary period, before boatbuilders realized that if you put a big wide stern on a workboat and crowd the power to it, then you are damn well going to need more bearing forward to hold the bow up instead of getting it pushed down by the force of following seas piling up against the wide transom. During this transitional period, fishermen were trapped in boats whose combination of wide sterns and narrow bows made them mean to steer with any sea behind….”

We’ll build Diablo with sheet-plywood panels held together by composite joints. That is, we’ll cut the panels to shape following expanded patterns shown on the plans. Then we’ll assemble them with tacks (actually 18-gauge nails), which will hold the hull’s shape until we can permanently secure everything with fiberglass tape, epoxy, and filler.

This is the “tack-and-tape” building method. In theory it’s essentially identical to the simple “stitch-and-glue” technique that has produced thousands of home-built kayaks; but instead of twisting plastic or wire ties to join the panels, we’ll drive lots of small nails. Payson sees advantages: “You’re spared the need to drill holes to lead the wire through, and you don’t have to wreck your hands twisting the ends together…. I hate working with wire.” Neither method requires close fits or much beveling. Both methods demand considerable grinding and sanding if we’re going to achieve a yacht finish.

Henry and Sam built BONITO with 1⁄4″ and 1⁄2″ exterior-grade fir plywood panels. They used spruce framing lumber for the thwarts and trim…all from the local lumberyard. Although they worked precisely to the Diablo hull shape as drawn by Bolger, the father-son team modified a few details. They built a useful locker below the ’midship thwart. A nifty foredeck adds more room for stowage and flotation, without spoiling the graceful sheerline. Additional lockers and flotation will be found below the quarter seats.

Photo by Henry Whittemore

Photo by Henry WhittemoreOptions abound for the boat’s layout. Sam Whittemore and his Dad, Henry, found stowage space under the thwart and foredeck. A center console would work on this hull, too.

Might we consider other alterations? On occasion, some folks (often professional watermen) like to stand erect while driving boats of this type…for improved visibility and to allow their knees to act as shock absorbers. We could install a steering console, but I’d be inclined to avoid the expense and dead-stick vagueness of remote controls. Instead, a robust 3 1⁄2′-tall post installed somewhere abaft the ’midship thwart would give us a firm handhold when we’re standing and steer- ing directly with a tiller extension. These stanchions (sissy bitts, chicken posts, idiot bitts…call them what you will) cost little and spoil less space than consoles. Of course, we’ll employ them carefully and in reasonable sea conditions.

So, here you have an easily built skiff that performs as well as (or better than) its store-bought competition, and the Whittemores have proven it to be a rewarding family project. Go for it!

Diablo Particulars

[table]

LOA/15′

Beam/5′

Power, maximum/25-hp outboard

[/table]

A narrow bottom and wide, angled bilge panels combine to give Diablo an efficient planing surface and predictable banking in turns. She has great dynamic stability at speed.

The Diablo Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2009. Plans and full-sized patterns for the Diablo are available from H.H. Payson & Company. Small-scale plans and building instructions for Diablo are included in Build the New Instant Boats, by Dynamite Payson, available from H.H. Payson & Company and The WoodenBoat Store. The book’s small-scale plans were intended as illustrations only, not for reading text and numbers; the plans and patterns from H.H. Payson & Company are recommended for building the Diablo.

What is the length, what is the beam? weight? speed? fuel economy?Lots of salty words in this article, but no details. I’d say most subscribers to this magazine are after a bit more detail.

The original article, published in Small Boats 2009, included some details along with the drawings, but those details didn’t making it into this reprint. I’ve added the “particulars” above the drawings. The weight had been listed as “Weight (with motor) 150 lbs” but that seems to be an error as a 25-hp outboard alone could weigh close to that amount. I couldn’t find a weight listed with any source for the plans, but a WoodenBoat Forum discussion in which Diablo builders participated suggested that 150 lbs may be an underestimate and 175 lbs more likely.

—Ed.

The Diablo is one of my very favourite boats. Fast with a huge carrying capacity. Stable enough and the ride is good. Handling at speed is impeccable.

With some that we built we extended the central transom knee forward with a piece of 2×2 to the next bulkhead to stiffen the bottom up at the back but wouldn’t dream of altering anything else.

MIK