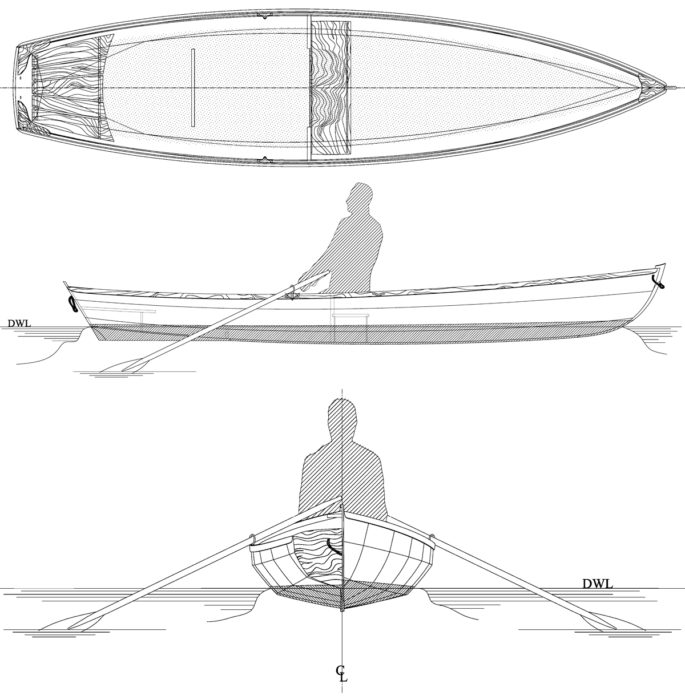

When Sam Devlin of Devlin Designing Boat Builders was commissioned to build a rowing skiff to be carried aboard a 45′ motoryacht, he was given two requirements: it had to be short enough to fit on the yacht’s cabintop, and it had to be equipped with a sliding-seat rowing rig. It’s a challenge to design a short boat that will perform well with a sliding seat, but Duckling, the sleek 14′ skiff Sam drew up and built, appears to fit the bill nicely.

In a boat equipped with a sliding seat, the movement of the rower changes the trim of the boat with every stroke. The length of a racing shell keeps the resulting porpoising to a minimum, but Duckling is designed to support the rower’s weight at the ends of the stroke by carrying a lot of reserve buoyancy above the waterline. When the rower slides aft to take a stroke, the flare of the hull at the base of the transom keeps the stern from settling too deep in the water. At the other end of the stroke, the rower’s weight has moved forward, and the overhang of Duckling’s bow and the flare of its forward sections help counter the downward pressure.

Photo by Christopher Cunningham

Photo by Christopher CunninghamDuckling, a pulling boat designed by Sam Devlin for stitch-and-glue construction, was a custom commission. The boat was meant to be carried atop a motoryacht; it may be carried atop a car, too.

Typical of Devlin’s boats, Duckling is built with stitch-and-glue plywood. The three planks on each side are cut from 9mm mahogany plywood and then temporarily wired to each other and to the transom. Fiberglass and epoxy applied to the seams creates the permanent bond. The resulting structure is light and strong and requires minimal bracing. A single plywood frame amidships supports a fixed thwart and, paired with a bulkhead at the forward edge of the thwart, it creates a compartment for foam flotation. A similar compartment in the stern supports a woven cane seat for a passenger. The rest of the hull is uncluttered except for a pair of drain plugs. To withstand the rigors of being stored uncovered on the motoryacht’s cabintop, Duckling’s interior was finished with a thick coating developed for use as a truck-bed liner. Enamel would serve well for a Duckling stored out of the weather.

The 18-lb Piantedosi rowing rig rests on the hull and thwart and is held in place by brackets that connect the outriggers to the gunwale. The anodized aluminum rig has a solid feel and took the strain of my pulling at full power without flexing or creaking. The 9′ 6″ carbon-fiber hatchet-bladed sculls manufactured by Dreher are very light and balance well in the locks.

Underway, Duckling managed the sliding seat well. The stern had plenty of bearing to pick up my weight at the catch of the stroke; its settling in the water was scarcely noticeable. As you might expect, the bow, being finer than the stern, has more vertical motion when the boat is under way. While Sam was rowing I could see the bow travel a vertical 3″ to 4″, but when I was rowing I wasn’t able to feel any adverse effects of the pitching. Even if I let my weight fall heavily toward the bow at the end of stroke, Duckling didn’t slow down perceptibly or wander off course.

Photo by Christopher Cunningham

Photo by Christopher CunninghamReserve buoyancy in Duckling’s stern allows for passenger carrying. The sliding-seat unit may be dispensed with for fixed-seat rowing.

Duckling has a waterline length of about 12′ 6″ feet and a theoretical maximum hull speed of 4 3⁄ 4 knots. It didn’t take much effort at all to bring her up to that 1 speed. Using a GPS as a knotmeter, I measured 4 ⁄ 2 knots to 4 3 ⁄ 4 knots when I was just loping along. Even rowing at dead slide (the seat in a fixed position), I could easily manage 4 1⁄ 2 knots. Going all out added a bit of speed, but I couldn’t push much over 5 1⁄ 4 knots. At that speed the curdled stern wake starts crawling up the transom. With a 72-lb kid sitting in the stern, the trim was not too far out of whack and I could still drive Duckling up to 5 knots.

The long oars make Duckling delightfully maneuverable. Four strokes—two forward strokes on one side alternated with two backing strokes on the other—will spin Duckling 180 degrees in short order. Even though its beam is under 40″, the hull has very good stability. Standing up on the thwart, I felt quite steady. I could also lean on the gunwale to look over the side and still feel safely supported. You could easily go fishing in Duckling and reach over the side with a net and not wind up swimming.

The rowing rig takes up a fair bit of room in the boat, limiting what you can carry, and the outriggers make it awkward to come alongside a dock or another boat. Duckling would serve best as a tender with the rowing rig removed. Accordingly, Devlin has designed Duckling to be rowed without the sliding-seat rowing rig. Gunwale-mounted oarlocks would take 7′ oars. With its slender shape, Duckling would still be quick and easily driven from the fixed thwart. Rowing from the thwart would also drop the rower’s weight several inches, making the boat more stable and providing more inboard clearance for the oars when rowing in rough water.

Photo by Christopher Cunningham

Photo by Christopher CunninghamDuckling is built of plywood, using the stitch-and-glue method. The 14-footer weighs 80 lbs.

For the yachtless, Duckling could be cartopped, though its 80-lb weight (without the sliding-seat rig) would require an extra hand for lifting to the roof racks. The solo boater could lift the bow to the back rack, then lift the stern and slide Duckling forward. A light trailer would probably be a better choice if you wanted to keep out of the chiropractor’s office. With just three planks to a side and minimal interior structure, Duckling would be a quick project for the amateur boatbuilder, and its size would be a good fit for a workshop squeezed into a single-car garage.

I should mention that I’ve never cared much for the idea of taking the outriggers and sliding seats meant for racing shells and putting them in a boat designed more for seakeeping ability than speed. The sliding-seat stroke may be graceful pushing a racing shell at 9 knots over flat water, but it can lead to bruised kneecaps and bloody thumbs shoving a rowboat at 2 knots across a beam sea. Duckling, though, is a brilliant idea for the couple who commissioned her. Wherever they find a quiet place to anchor, they’ll have a suitable place to row, and with Duckling they’ll have the perfect form of exercise to reinvigorate themselves after a day at the helm.![]()

The Duckling prototype garnered much attention, and the design is now available to home-based builders. A modest sail plan was in the works at press time.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2009 and appears here as archival material. Plans for the Duckling are available from Devlin Designing Boat Builders.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.