Dories, dories, dories. Perched above the mighty Merrimack River on Main Street in Amesbury, Massachusetts, Lowell’s Boat Shop is a boatshop built by dories, many thousands of dories over a great many decades. The building one sees today is old in a general sense but, dating to around 1860, it wasn’t erected until about 67 years after Simeon Lowell started building boats on the site in 1793. By the time Simeon’s progeny had more or less perfected dory mass-production methods in the mid- to late-1800s, the shop’s capacity was staggering. Figures burned into a wooden beam indicate that in 1911, 2,029 boats were built, probably a record.

The Lowell model under discussion here might be thought of as the answer to this question: What do you get when you cross a Lowell dory with an outboard motor? Answer: a Lowell Amesbury Skiff.

“Our design,” said the shop’s lead builder, Graham McKay, “is essentially a Lowell Surf Dory from the middle part of the boat forward.” The Surf Dory (see Small Boats 2011) is “round-sided” by comparison to Banks fishing dories. (“Knuckle-sided” is considered a more descriptive term as the frames are not curved but have variously angled flat sections where planks attach.) But what about the Amesbury’s hull shape from amidships to transom? That’s where the skiff part comes in. While the Lowell Surf Dory’s hull narrows to a traditional tombstone transom at the stern, the Amesbury Skiff remains beamy from midsection to stern, and the flat bottom ends at a broad transom. The result is an outboard hull that will plane. It’s a boat type known generically as a “dory skiff” or “semi-dory,” though not all such boats are as decidedly outboard-oriented as this one.

The Amesbury Skiff is offered in models ranging from 12′ to 20′. Like other Lowell models, this one is built upright using the old, original patterns for frames, stem, and bottom, along with the garboard, or lower-most, plank, thus ensuring a certain level of both labor efficiency and consistency. This means, of course, that Lowell’s builds completed boats but does not have plans available, although a similar boat was documented by John Gardner in his The Dory Book, and the plans are reproduced here.

Stan Grayson

Stan GraysonInstead of using plans, Lowell’s Boat Shop relies on tried-and-true patterns developed and refined over time for every piece of each type of boat.

What may come as a pleasant surprise to many is that this wooden boat can live happily on its trailer. “What you see,” McKay said, “is essentially a traditional boat atop a plywood and epoxy foundation.” Such newfangled yet useful innovations were introduced after Lowell’s was sold in 1976 to the late Jamieson “Jim” Odell. Odell was an out going, remarkably insightful man who combined business and engineering experience with a passion for wooden boats. Odell introduced epoxy, marine plywood, and fiberglass cloth to the shop’s repertoire of materials. The caulked fore-and-aft bottom planking typical of dory construction was replaced by Lloyd’s-certified meranti plywood. Plywood is also used for the garboard strakes. The outside of the hull is ’glassed with 6-oz cloth from the garboards down. On the interior, the bottom, the lower portion of the frames, and the lap between the gar board and the broad strakes, which are the second plank up from the bottom on each side, are all coated with epoxy.

These maintenance- and leak-reducing innovations are combined with traditional dory construction elsewhere in the hull. The knees and stem are oak, the frames oak or locust. Plank stock is Atlantic white cedar, pine, or cypress, depending on preferences. Bronze ring nails fasten the planks to the frames, while the laps—where one plank overlaps the other—are fastened with copper rivets.

Putting together a boat in this fashion according to techniques practiced by long-gone generations of Lowell craftsmen would be more of a challenge than it is without Jim Odell’s foresight. Odell made sure that longtime builder Fred Tarbox stayed on to teach the “Lowell way,” and the collective wisdom of the past was preserved in a big three-ring binder known at the shop as The Book. “The Book,” McKay said, “was the key to making it possible for those coming here after the Odells to be able to build a boat that carries on the shop’s unique methods. We call those methods ‘Lowellisms.’”

Space doesn’t permit going into detail about Lowellisms, but they describe a basic dory construction in which planks fit flush to the flat portion of the frames only at the laps, resulting in what McKay calls a “certain amount of desirable flexibility.” There is a prescribed method for using a straightedge to measure up from specific points on the bottom as an efficient way of outlining planks. The Book has instructions for how much to “tip out” the forward frames to deliver the desired spray-reducing flare in each hull. A note instructs to alter the rocker—the longitudinal curve of the bottom—to make it slightly “negative,” or bend downward, for the aft end of the 14′ Amesbury Skiff’s bottom, as is done on the other models to improve performance on plane.

Stan Grayson

Stan GraysonThe larger skiffs, like the 16-footer shown at left, have center-console steering, and this boat also has enclosed storage beneath the forward seat. The boat is stoutly built, with white oak for the stem, breasthook, rails, and stern knees, and with its plywood bottom and cedar topsides, it is tough and easily trailerable.

Each Amesbury Skiff is fitted out to meet individual preferences. The 12′ to 14′ models are tiller steered, but those 16′ or longer are usually set up with consoles. A storage locker is built into the bow thwart and other thwarts as desired. McKay is ever watchful regarding weight distribution. “We just did a 13-footer,” he noted, “and because of the enclosed stowage compartments the owner wanted back aft, we compensated by mounting the battery and fuel tank in the bow locker to even out the weight.”

Three finish levels are offered. The standard all-paint finish includes a primer coat and three top coats. Yacht finish includes varnish on the transom, rails, and thwarts. The shop will also deliver a boat with just the primer coat and encourages some customer participation in a boat’s construction.

We had a chance to use the 16′ model on the Merrimack one splendid day in September. While dories can be tippy when boarding, the Amesbury Skiff is quite stable. That can be particularly important in a family boat that may often have non-boaters aboard. This hull is very easily driven and certainly doesn’t require its rated maximum horsepower—35 hp for the 16-footer—to deliver satisfying yet economical performance. I’m afraid that we rather exceeded the river’s speed limit for a brief period and have it on good authority that 25 hp will drive the 16′ to over 25 mph while 40 hp will push the 18′ to the high 30s or more. Such velocities, however, are largely academic, for this is not a speedboat. The Amesbury Skiff will be at its best for all manner of less frantic explorations, family outings, fishing, and utilitarian purposes.

We encountered no seas on our river journey, only a few wakes through which the well-balanced boat rode smoothly. With the hull banked into a turn, the lapped planks add stability. One gets the impression that the boat possesses enough seaworthiness to venture beyond the river’s mouth in fair weather. Typical of most flat-bottomed boats, this one requires some practice to dock gracefully in a breeze. Twin skegs mounted on the bottom aft certainly are a plus in this regard. This is a boat that will teach the newcomer nuances of powerboat handling and seamanship while rewarding the more experienced with its capabilities. Of course, a pair of good 8′ to 9′ oars should be kept aboard. A 16′ or 18′ Amesbury Skiff is no rowboat, but, if necessary, either can be rowed from the forward thwart.

A wooden “dory skiff” like this, professionally built of both solid lumber and plywood, is a comparatively rare commodity these days. Yet, one can acquire a 16′ model with console for around $11,000 to $13,000 and then have it rigged with the preferred motor. Right now, I’m picturing a white hull with a buff or light gray interior, painted or bright rails and a shiny, white, 25-hp Evinrude with power trim and tilt. A fully equipped 16-footer would probably weigh around 600 lbs, making it readily trailerable behind even a small vehicle. For that reason, a nice-fitting cover should be included in the budget.

The Amesbury Skiff represents good value in a salty boat that will both teach and provide years of stress-free enjoyment. If you’re debating ordering one, remember the words of America’s great poet John Greenleaf Whittier, who lived in Amesbury from 1836 until his death in 1892 and who frequently walked up on Friend Street—sometimes accompanied by his pet squirrel, Friday:

“For of all sad words of tongue or pen, The saddest are these: ‘It might have been.”![]()

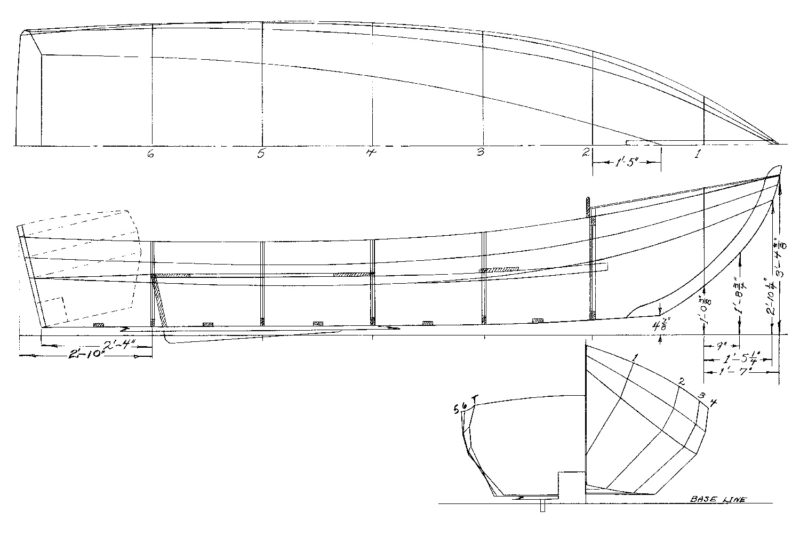

The lines plans shown here for a 16’ outboard-powered “semi-dory” were published in The Dory Book (International Marine, 1978) by historian John Gardner, who called it “a big, small boat.” The plans, which are shown for comparison, describe the alternative of an outboard well (which Lowell’s also offers) and the author felt 15 hp would be “useful and normal.” 16′ Outboard Semi-dory Particulars: LOA 16′, Beam 6′ 5″ Lowell’s Boat Shop 16′ Amesbury Skiff (plans not available): LOA 16′ 1″, Beam 6′ 5″, Depth amidships 21″, Weight ~300, Rated hp 35 Note: The boat is available in lengths of 12′ to 20′.

—

Completed Amesbury skiffs are available from Lowell’s Boat Shop.

1955, my dad bought me a 12′ dory with a quarterdeck on the bow. I has a 1955 Johnson outboard 5-1/2 horsepower motor. Almost lost her in the Hurricane of 58. Sank at the mooring safe and sound, just needed seats and floor boards gone. Easy fix, I wish I had it today.

I later worked for Pursuit Boats as a salesman on the road. The beginning of my career in the boat business. What a start!