Fenwick Williams designed 17 catboats from 8′ to 30′ in length. All of them are legendary, but his first, an 18-footer created during the height of the Great Depression in 1931, stands out as a little gem.

Originally intended to be an inexpensive craft for people who couldn’t afford larger boats, Design No. 1 remains popular today because of its perky appearance, comfort, and lively performance. Her stability and ease of handling accommodate young and old, from a software designer escaping the digital world to a traffic-weary bus driver seeking peace and quiet. Retired senior editor of the Catboat Association, John Peter Brewer describes this family of boats with both accuracy and affection:

“The catboat is …an American art form. She was developed, built and sailed with great skill by ordinary men who needed her for honest work. Her origins go back at least 160 years, and perhaps more.

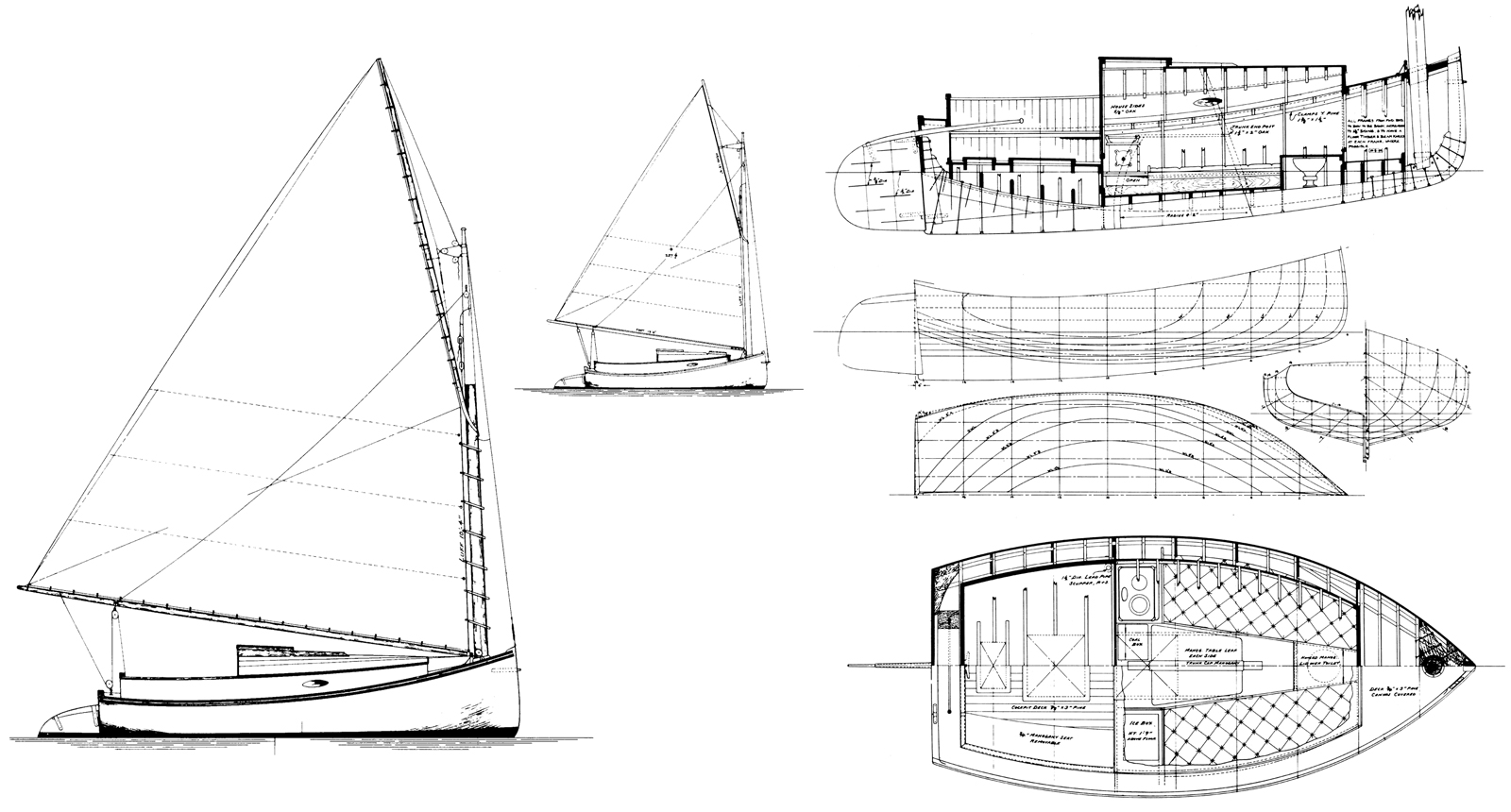

“…the hull is wide and the big, gaff-rigged sail is set on a strong mast with a single forestay well forward near the stem…the sail is controlled with a topping lift, lazy jacks, separate throat and peak halyards, [and] reef points…. The gaff main is not meant to be picturesque. It’s to lower the center of effort, give more drive off the wind and allow more control through the peak halyard and topping lift…. The classic catboat has a plumb stem, high bow, and big barndoor rudder. Those cats 17 feet or more usually have a cuddy cabin with two bunks and the rudiments for overnight sailing.”

With her large cockpit, easily handled sail, and anchor on the bowsprit, LYDIA is ready to take the whole family for an afternoon sail or an all-day picnic. If it gets late, there is room for all hands to spend the night, with the kids sleeping under a boom tent.

As Brewer describes it, the catboat was originally a working boat with features designed for the fishing trade. For example, if you slack out the mainsheet and put the helm down, she will come up into the wind and to a virtual stop, ready for hauling lobster traps or shellfish nets. A friend of ours used to startle the committee boat judges at informal mixed-class “chowder races” by pulling up to within a couple of yards of the starting line and letting the mainsheet run. While all of the Bermuda-rigged boats tacked for position, he simply waited there until the starting gun, when he hauled in the boom and started sailing. He was inevitably first across the line at the start— although seldom at the finish. Another advantage to the gaff rig is the ability to lower the peak in a sudden blow. Called the “fisherman’s reef,” this maneuver spills air and helps maintain control of the boat.

After finishing Harvard Graduate School in the summer of 1967, Frank Cassidy answered an ad for a partially completed catboat. “I didn’t know what a catboat was,” he confesses; “I think I was probably expecting something with two hulls.” Actually, it was a weathered 18′ single hull, with only a few planks installed below the sheer, most of which had to be replaced; a pile of lumber; some screws and bolts; and a set of plans for Fenwick Williams’s Design No. 1. Except for the cross spalls spanning the sawn and steam-bent frames, there was nothing on deck, or above the sheer—the interior was totally open. He bought it all for $250.

Completing the boat took most of Frank’s spare time over the next five years. Frank christened the completed 18-footer KITTY KELLY, his mother’s nickname. She was launched from Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, in the spring of 1973. Over the next four years, Frank and his wife Lynda cruised her from nearby Marion with their two small children.

My late wife Jane and I first saw KITTY KELLY sitting on the trailer Frank had made. She had a prim white hull topped by caramel-colored teak cabin and coaming, with mint green Dynel on plywood decks. Her profile displayed all of the big catboat design elements in miniature, balanced and poised to go: a well-proportioned outboard rudder, plumb stern, and springy sheer swooping forward and upward to a snappy stem with just a touch of tumblehome. She was for sale and, clearly, she wanted to go home with us. That she did, and flying in the face of superstition, we rechristened her AUNT LYDIA after a favorite relative.

From 1978 to 1985, we explored the New England coast from Hingham, Massachusetts, to Kennebunkport, Maine, accompanied by our 28-lb Sheltie. We poked around little coves and rivers, confident that our 2′ draft (with the centerboard up) would allow us to glide over shoals. AUNT LY DIA gave us nothing but good luck, economy, and convenience. Eschewing yard fees, she sat comfortably covered in our driveway during the winter. Her size was ideal for trailering to a ramp for a spring launching. We opted to lace the sail to her mast, which proved quicker to rig than the traditional hoops and easier to raise and lower as well.

Getting underway for a month’s vacation or a Sunday afternoon day sail is a simple matter of raising the luff with the throat halyard and peaking the gaff; both operations are performed from the cockpit. The only reason to go forward is to drop the mooring line. The moment you fall off on one tack or the other and start to move, the balance of this design becomes abundantly apparent. In a moderate-air reach, I could connect the tiller and mainsheet in a makeshift autopilot. Even in a stiff breeze she has only enough weather helm to give you the feel of the boat through the tiller, but not so much as to invite an arm-wrestling match. She rides in the water with confidence, going smoothly over swells, and flattening all but the most violent chop.

Like the saucy young clipper spotted on Paradise Street in the sea chantey “Blow the Man Down,” AUNT LYDIA is bluff in the bow. In fact, her bow is so full that one imaginative Marbleheader, Rodney Bowden, named his sister 18-footer (built in the late 1940s by Charlton Smith) BUXOM LASS. The reason for this fullness is buoyancy. Fenwick believed that a sharp bow on a catboat with its large sail set well forward tends to dig into the water, giving a heavy weather helm on close reaches and slowness when tacking. Williams positioned the centerboard trunk alongside the keel instead of cutting a slot through it. His keel is slightly deeper for extra stability with the board up. Another characteristic of his designs is a moderate and consistent deadrise from amidships to the stern. The resulting lifted quarters combined with the fullness forward prevents the bow from depressing when heeling.

Photo by F. Marshall Bauer

Photo by F. Marshall BauerSome of the catboat’s traditional characteristics are the single gaff sail with its mast stepped well forward, cat’s-eye (elliptically shaped) portholes in the cabin sides, and a barn-door rudder.

A standard catboat’s beam is roughly half of its overall all length. This 18-footer’s 8’6″ beam creates a compact but cozy living space belowdeck. Her cockpit, made extra large in the working catboats to hold a haul of cod, scallops, or oysters, makes an ideal parlor for afternoon wine parties. We had a boom tent made, wherein we spent many a rainy afternoon reading and listening to music. The high coaming, originally intended to keep large following seas out, is also excellent for keeping active toddlers and pets in.

Frank Cassidy’s objective was to provide for a family of four sleeping inside the cabin in safety and relative comfort. He accomplished this with an ingenious arrangement of rails and two triangular inserts which sat on the rails to fill the gaps between the settees and the table. Two triangular cushions completed the double bunk for four.

We replaced KITTY KELLY’s 6-hp Evinrude outboard with a 9-hp Mercury. A couple of years later, Bob Cloutman of Marblehead installed a Universal Atomic Two inboard, which worked like a charm and, with the outboard bracket removed, gave us a more classic stern.

As an alternative to carvel planking, Australian Michael Storer reworked the structure to be built in cedar strips by David Wilson of Duck Flat Wooden Boats for Rob O’Callaghan. He describes some of his changes: “First, the boat is very much simpler. All ribs, knees, bilge stringers are eliminated, giving a much cleaner interior and cutting the labor required to build the hull to a fraction of traditional methods. Many other parts can be combined compared to the original design—sheer clamp and deck clamp can be combined, and the stem and backbone can be simplified into a simple scarfed structure with the hull skin itself acting as a knee between the two members.

Photo by F. Marshall Bauer

Photo by F. Marshall BauerGhosting along on a starboard tack, LYDIA shows Fenwick Williams’s saucy sheerline to good advantage. The green bottom, without a boot-top, is reminiscent of old-time yachts.

“The result is an immensely strong monocoque construction with loads from one area being dissipated into many others. There are no lazy bits of boat. The cabin and cockpit seat tops and fronts stiffen and support the hull skin, transferring loads into the bulkheads and centerboard case. This boat is much stronger than the original design, and much faster and cheaper to build because of the structural simplification.

“One of the aims was to create a boat that could live on a trailer without any risk of drying out the planking so that it would start to leak, or [risk of] trailering loads damaging hull integrity.”

Misty-eyed, we had watched Fenwick’s double-ended yawl ANNIE being built at the Arundel Yacht Yard in Kennebunkport. When the original owner put her up for sale in 1985, we could not resist. We said a reluctant goodbye to AUNT LYDIA. Today, 35 years later, I’m happy to report that our old boat is still sailing—happily frisking about Dorchester Bay as LYDIA under the able care of skipper Larry Yeakle, a Boston University Law School professor.![]()

Fenwick Williams’s original drawings for his 18′ catboat specify carvel planking and solid backbone timbers. The boat has been built, however, in cedar strips and epoxy, creating a structure that can be dry-sailed.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2009 and appears here as archival material. Boat plans for the Williams 18′ Catboat are available from The WoodenBoat Store.

Had one of these built at the Apprenticeshop, modified design by the late Joe Liener who saw one being built after the war. He went home and built BUXOM LASS of Salem. Mine was GOBLIN with an old-time rig which meant the first reef in at about 10 knots, but I rarely needed the outboard. My old boat is still sailing, now on Narragansett Bay.

Is it really over 3,000 pounds as advertised?

I suspect that I once came across AUNT LYDIA on a launching ramp in Hingham Harbor. This was decades ago but the memory stays with me, despite ownership of a few less memorable cats since. The proportions seemed just right. And, the wood hull brings own wonderful feel to the beholder. Fenwick Williams was a genius.

I would very much to talk to F. Marshall Bauer. I have a Fenwick Williams 18′ from 1955 I rescued and will be restoring (shown as ‘Patchy Fog’ in ‘The Catboat Book.’). Could someone let me know how to contact? Thanks.

Sadly, according to an obituary published on the web, Mr. Bauer passed away in July, 2021.

—Ed.

Thank you for republishing this. Wish I had one. While sailing near Shady Side, MD, last summer I watched a fleet of catboats jauntily sail out of the West River into the Chesapeake and they were a sight to remember.