Lawrence W. Cheek

Lawrence W. CheekThe classic transom-sterned skiff that became known as the Sid Skiff, here with cobuilder Zach Simonson-Bond at the oars, first came to Ray Speck’s attention while he was living on a houseboat in Sausalito, California. The boat is as much as joy to look at as it is to row.

So what modifications do you think might make it point a little higher?” I ask, following an embarrassing moment where I boggle an attempted tack. “Drop the rig and row,” answers Ray Speck, who’s built about 20 of these boats.

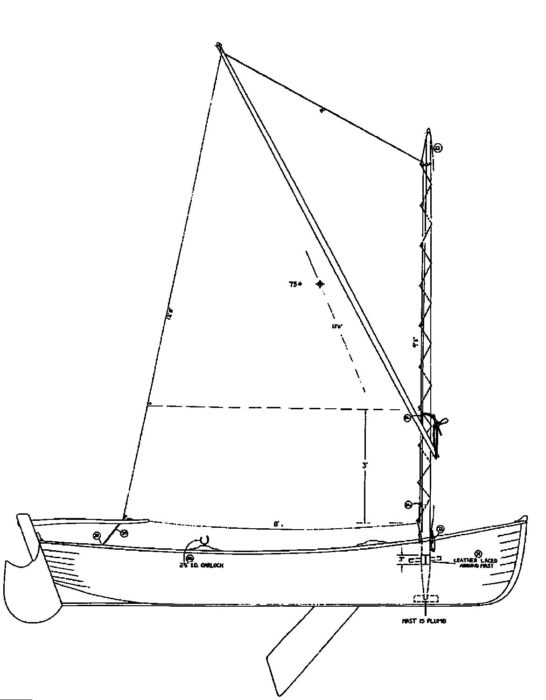

A perfectly practical solution, for sure, and one that resonates nicely with the Sid Skiff, a boat that’s as practical and adaptable as it is pretty. Okay, it’s not about to claw upwind like a sloop. But it also doesn’t suffer from a sloop’s rigging complications. As it is, it’ll reach off the wind in a wisp of a breeze, and it glides so deftly and easily under oar power that on any given day’s outing, it would be a crime not to include an exercise leg.

“I built one with a 19′ mast,” Speck recalls, riffing on the Sid Skiff’s versatility. “It had maybe 150 sq ft of sail. The guy who bought it was sailing in Raccoon Strait off Sausalito, and he swore it broke away on a plane. And he weighed 195 lbs. His wife, who weighed about 110, capsized in it.”

Speck, who retired in 2012 from teaching at the Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding in Port Hadlock, Washington, has a long and intimate history with this boat—though the crucial first chapter is missing. He first encountered the design in 1969 when he was living on a houseboat in Sausalito, California, and frequently noticed the harbormaster, Sid Foster, rowing around Richardson Bay in a lovely little lapstrake skiff. “We all lusted after that boat,” Speck says. “When Sid died, one of my friends got the boat, and another friend thought he was supposed to have gotten it. A battle ensued. I said, ‘Wait a minute, guys—why don’t I just build you another one?’” Speck took the lines off the disputed bequest and built a slightly larger version, giving new life to a classic design. Speck named it the Sid Skiff in Sid Foster’s honor.

Only trouble is—whose design was it? Speck doesn’t know. He asked around the Bay Area and heard a vague rumor that it had emanated from the Puget Sound area. Much later, after he’d moved to Port Townsend to teach, he happened to peer closely at a 1950s photo of a Prothero Brothers schooner on the wall. Tied up at a Seattle dock next to the schooner was a Sid Skiff —he says it was unmistakable.

Speck thinks the design was originally a production boat; the clues were certain signs of construction expedience. “It was down to the fewest possible number of parts,” he says. “Six planks to a side, with sawn frames. It looked like they were able to crank ’em out pretty fast.”

Lawrence W. Cheek

Lawrence W. CheekA boomless sprit rig, which is simple to set, strike, and stow, moves the Sid Skiff well in favorable winds. She won’t point as high on the wind as a marconi racing sloop, but asking her to do so is a pointless exercise when it is so easy to strike the rig and row.

Speck has slightly fancified the construction. There are now eight or nine planks per side, and the detailing is careful and elegant. Still, it isn’t a complicated boat. Speck, now 69, says he used to be able to complete one in about 250 hours. He figures an amateur could build a Sid from his five pages of plans in 500 to 600 hours. And for any builder, the design welcomes variation and adaptation. Speck doesn’t mind a bit. He has built iterations from 12′ to 18′ with one, two, and three rowing stations. The builder simply spaces out the molds to vary the length. The plans specify 3⁄8″ fastened lap planks, preferably cedar or mahogany, but Speck says there’s no reason why glued-lap plywood wouldn’t work. For upwind fanciers like me, sailmaker Sean Rankins, who occupies the sail loft in the school’s main building, has developed a jibheaded sprit rig for a 16′ version.

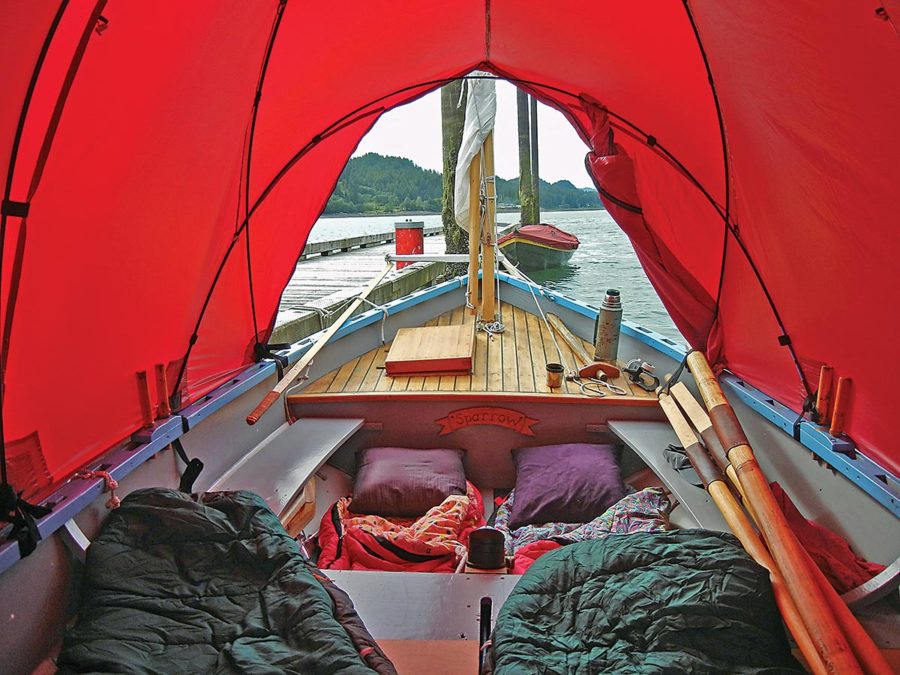

The 13′ 6″ Sid Skiff I sailed and rowed bears an unusual history. Chris Payton, a 1999 graduate of the Northwest School, began building it after his graduation but completed only the backbone, centerboard trunk, and transom before he died. The pieces made their way to the school, where they resided in the boatshop’s rafters for nearly a decade. At some point in the 2011–12 term, the Traditional Small Craft class was running low on project boats, so they decided to begin the planking. The 2012–13 class then finished out the interior and rigging.

As usual with the school’s project boats, the joinery is solid and tight and the details all look professionally executed. The faculty keeps a close watch on students’ work to ensure quality control. Wait: starboard bow, fifth plank down from the sheer clamp—what’s that? A conspicuously mismatched finger-width patch strip of not-exactly-red western red cedar. Speck thinks the students cracked the plank as they were bending it to the stem, then grabbed a random scrap of cedar to make a graving piece. One class was expecting the boat to be painted, but the succeeding class couldn’t bear to cover up the honeyed glow of red (and yellowish) cedar. So the discordant patch now affirms that the boat was crafted by fallible human hands, like the 18th-century harpsichord builders who always took care to incorporate an intentional mortal mistake so as not to irritate God.

Zach Simonson-Bond, a 26-year-old boatbuilding student from nearby Whidbey Island, worked on the skiff during the school year and now is exuberantly, uncontrollably in love with it. On the day I visited, the school drafted him to accompany me on a foggy morning outing on Port Townsend Bay, and he waited for me to finish interviewing Speck with barely suppressed impatience. Once underway, he explained that he used to crew on the historic Puget Sound schooner ADVENTURESS (see WB No. 232), which deployed another Sid Skiff as a tender.

Lawrence W. Cheek

Lawrence W. CheekThe boat built at the Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding is all about the beauty of wood, with western red cedar planking over oak frames, although glued-lap plywood planking would also work.

“People on ADVENTURESS regarded the skiff with so much affection,” he said. “Kids would have their first rowing experience on her. I honed my own rowing skills on her. She’s really easy to row, pretty maneuverable, really sweet lines. No, she doesn’t point too well.”

I don’t have much rowing skill myself, but after ten minutes with the skiff’s oars I sensed that the boat and I were finding an eerily magical groove, we were making good speed, and it felt wonderful. When we began to get a usable breeze and shifted to sailing mode, I was a little less enchanted. Although Sid made good progress in our stingy breeze, it wasn’t necessarily progress in my preferred directions, and the bay was crowded with moored boats that had to be dodged. It seemed to be making a lot of leeway, and it stubbornly refused to point high. I managed one slow tack, blew another, then figured out that Sid is happier obeying suggestions to jibe. After this the morning’s sail went better.

Lawrence W. Cheek

Lawrence W. CheekThe Sid Skiff is light enough to nose in to a beach for a shore outing.

The next day, I talked with sailmaker Sean Rankins, who built the sails for several of Speck’s and the school’s Sid Skiffs, and whom I’ve found to be an excellent authority on rigs of all kinds. What, I wondered, would improve the boat’s pointing ability?

“First of all, I might have trimmed the sail a little differently than you did,” Rankins said, with exquisite diplomacy. “It’s also very responsive to crew weight and position, and that could make a difference.”

Lawrence W. Cheek

Lawrence W. CheekThe mahogany transom, along with the backbone and centerboard trunk, waited a decade before helping a new generation of students appreciate the timeless design.

But more fundamentally, Rankins explained that if a Sid Skiff were to be tuned more toward sailing than rowing, several modifications would in fact be useful. “If I were having one built for my use,” he said, “it would have a higher-peaked main and definitely a boom. That would give better sheeting to weather and would better control the twist in the sail.” When I mentioned that the centerboard in this particular boat was limited to a 45-degree deployment, he added that a deeper-setting centerboard, or a daggerboard with larger area, would also improve the boat’s weatherly behavior and decrease its tendency to carve a lot of leeway.

My takeaway from our talk was not that he was critical of this particular boat, or Speck’s interpretation of the design, but that small boats are wonderfully responsive to personalization. It’s a sparkling argument for building one yourself or commissioning one from a professional shop—or a school. (The Northwest School builds boats on commission and speculation that range from the 7′ 7″ Nutshell Pram to a 62′ Bob Perry racer. This Sid Skiff was priced at $8,750.) Adding a jib or boom to the Sid Skiff’s sprit rig or trying out a balance lug might cost a few hundred bucks as opposed to the fluttering away of thousands involved in rig modifications to a big boat. And the physical forces acting on a small boat are small themselves, so mistakes and miscalculations tend not to escalate into disasters. Unlike most other aspects of our modern lives, errors and trials with a small wooden boat are fun. ![]()

Plans and finished boats no onger available from Ray Speck, or through the Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding.

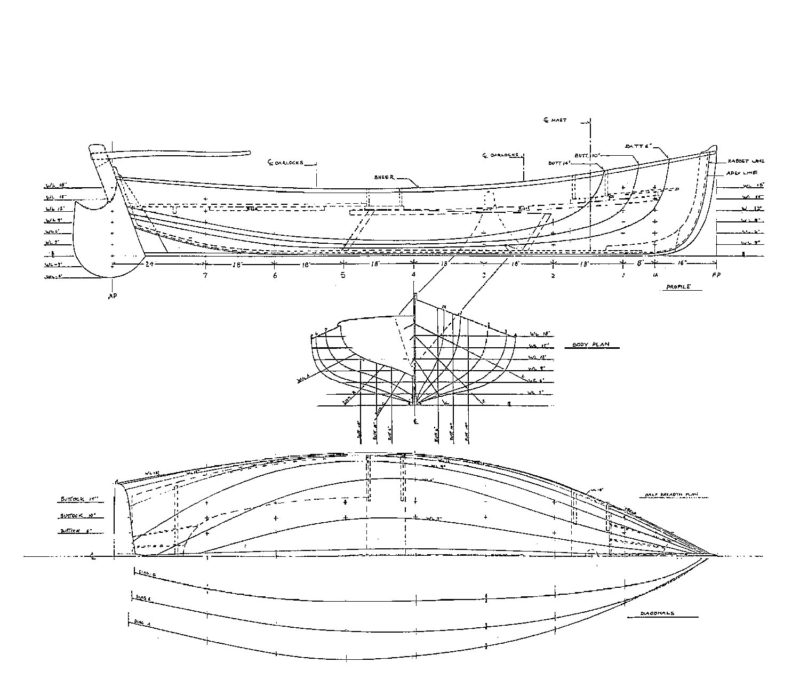

Ray Speck

Ray SpeckCaptivated by the shapely hull he first saw in Sausalito, California, boatbuilder Ray Speck got

to know the boat very well, having taken the lines off the original in the late 1960s. He has built

many of them since. The hull’s shape promises a comparatively easy planking job, with plenty

of opportunity to mind the details of fitting out. Everything about the boat seems well proportioned, the very essence of the word “classic.”

Particulars:

LOA 13’6″

Beam 4’9″

Draft, board up 10″

Weight 175 lbs

I bought a set of plans from Ray last year and plan on building one for myself this winter. Rowing only , as I like that exercise and slow exploring experience.

What a delightful skiff. If not from Mr Speck, where can one obtain the plans ? The horseshoe stern thwart alone is enough to make me want to build this gem – the other features are a real bonus – in an age when so many designers expect us to sit on the bottom boards and ‘squirm around’ when we tack , which can be tough on older knees ! A great choice by Small Boats !

James Burnett-Hitchcock

I knew Sid as the nicest harbormaster in the Sausalito Yacht Harbor back in the days when the boardwalk had Monk-designed Pacific Trawlers lined up. There was the Tides bookstore and next door was a real marine supply shop with mostly galvanized fittings and cool things like marlinspike knives. Some of the roads in town were still dirt and there were no parking meters. Bridgeway had the odor of linseed oil due to the real artist studios in town.

Sid was unique. We talked sometimes for hours after he would come down to the Bay Lady my brother owned to check up on me after midnight. Having a berth in the harbor then was as difficult as it ever was, but my brother Jerome sealed our relationship with the Madden family still existing today.

I think a copy of a larger version of The Sid sat under the Bookstore/Brokerage building for many years.

I miss those days, and seeing the pictures in this story are almost heartbreaking of what once was and how it is today.

Hi All,

I was on deck aboard my 20-ton gaff cutter C.A. MARCY alongside Lefty’s Pier at Gate Three in Sausalito in the early 1970s. Ray Speck rowed up along side in a beautiful 14′ lapstrake cedar Whitehall that he’d just finished. He asked me if I’d like to take it for a row. I jumped at the chance. I didn’t want a Whitehall but I thought that his workmanship was great! When I got back in a few minutes, I asked if he had an opening in his building schedule. He said that he did. I told him that I had been waiting to get set up myself or to find someone who could build me a copy of a boat called JANIE. He told me that the JANIE was sitting in his shop about to get an overhaul. JANIE was, of course, Sid Foster’s skiff, in the care of Scott Dimond after Sid had passed away. Six weeks later MARCY had a safety boat named SID. I still have the SID covered, on a trailer. For 25 years she enjoyed life afloat in saltwater with a daily saltwater rinse-down and pump out. I made up a boomless sprit rig, quick to set up and take down. She has thumb cleats on each quarter knee which turn the main sheet into the middle of the boat for tending. I have a trick mainsheet which gives a choice of single or two parts depending on the breeze. It’s done this way, there is a small Harken block seized to the clew of the sail. The end of the 7/16″ three-strand Dacron mainsheet is formed into a loop with a crown knot for a stopper at its juncture. For two parts the loop is hoocked on the quarter knee thumb cleat and the sheet leads up to the block at the clew and back down around the thumb cleat over the loop and to hand in the center of the boat. For single part, the loop is released from the thumb cleat and the crown knot acts as a stopper at the clew block. Voila, single part! Lateral plane is provided by a shifting leeboard that hooks over the gunwale at the thwart and is maintained upright by a line stoppered in a hole in the center thwart. This line goes through a hole in the top of the leeboard and comes back on itself with a rolling hitch. I have to say that even with shifting the mainsheet from side to side at the stern and shifting the leeboard to the new lee side I’ve never missed stays.

Cheers,

Lauren Williams

Hello All,

The comment about unavailable plans (above) has been overtaken by events. I received a set several days ago from Ray. He told me he printed another batch.

Regards,

Paul Eberhardt