I once worked in a New Hampshire cabinet shop with a gray-bearded guy named Paul who regularly offered only two criticisms of my craftsmanship. He would say either, “We’re not making a damn pigpen here,” or “We’re not making a damn piano here.” When I put the appropriate amount of effort into the job at hand, he’d let me be. If Paul ever looked over Joe Greenley’s shoulder as Joe built one of his strip-built kayaks, I think he’d sputter, “We’re not building a damn Louis XIV escritoire here.”

Joe has created quite a reputation for his company, Redfish Kayaks, by transforming strip-built kayaks into works of art. For years I’ve admired his craftsmanship at wooden boat festivals and kayak symposia in the Pacific Northwest, but I’d never paddled any of his boats. I suppose all I had to do was ask, but I was as reluctant to paddle one as I would be to use a guitar as a garden rake.

When I finally got a chance to paddle a Redfish kayak, it was a King built from a kit by Dale Meland under Joe’s tutelage. Dale was a disciple of decorative strip-building and did a first-rate job with his kayak’s sweeping patterns and pinstripes of Western red cedar, Alaska yellow cedar, and walnut. It was fine piece of craftsmanship, but it didn’t take long for me to realize that the kayak wasn’t just fancy woodwork; it was as much a pleasure to paddle as it was to admire.

Photo by Michael Berman

Photo by Michael BermanWhile the King kayak is for the intermediate–to–advanced paddler, the boat will introduce a willing rank beginner to the pleasures of good handling characteristics.

Redfish lists the King at 38 lbs. Dale had made a few modifications that brought the weight up to 43 lbs—still about a dozen pounds lighter than most fiberglass kayaks and an easy lift for cartopping. The cockpit is located a bit farther aft than is typical of most touring kayaks, so the balance point fell at the forward end of the coaming. While that made the boat a bit bow heavy for carrying slung over one shoulder, it was ideal for my preferred method of carrying: facing the stern with the kayak upside down and the coaming resting on both shoulders. That’s how Greenland kayakers carry their kayaks, especially when competing in races that include a portage; it’s a lot easier on the back.

Dale’s King had an optional feature called the Roller’s Recess. The recess is scooped out around the cockpit nearly to the sheerline and drops the aft end of the coaming well below deck level. The configuration gave me a range of motion that was equal to that of the low- profile Greenland kayaks I’ve built specifically for rolling. I could lie back and touch my head to the aft deck without having my hips lift out of the seat.

Photo by Christopher Cunningham

Photo by Christopher CunninghamThe Roller’s Recess is a Redfish trademark. This feature lowers the after portion of the cockpit coaming, allowing for easier-than-usual rolling.

Perimeter grab lines and bungee cords were secured by short loops of webbing anchored in slots cut into the foredeck. This installation of deck lines won’t snag clothing or ding knuckles during rescues and re-entries. It’s also visually unobtrusive; through-bolted plastic padeyes would detract from an artfully crafted deck.

Dale sculpted a mini-cell foam seat for a custom fit, and fortunately the contours were a perfect fit for me, too. The seat, hip pads, and backrest securely cradled my hips and encouraged an upright posture conducive to proper paddling technique. The foredeck was relatively low for a touring kayak and sloped down to the sheer well out of the way of the paddling stroke. The trade-off was diminished space in the cockpit, but I still had just enough foot room for my size-13 neoprene booties.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamStrip-planking allows for myriad design options.

A float, the King provided a comfortably stable platform. Even in choppy water I could rest the paddle across the cockpit coaming and have both hands free to write in my notebook. While paddling in the shoals and getting slapped on the beam by breaking waves, it was easy to keep the hull underneath me. The secondary stability was excellent. Only when I canted my hips to the limits of my flexibility could I feel the stability begin to fall off, and by that time I had the coaming dipped into the water. I normally heel, or “edge,” my kayak when carving turns; this makes the boat much more responsive. When doing so in this test, the King offered plenty of righting moment for a very secure feeling. It took only a slight edging to get the King to respond to a sweep stroke with a crisply carved turn. When I wanted to maneuver in tight quarters, a bit more edging would get the stern to swing around smartly.

For speed trials, I ducked into a marina where I could find some still water and get out of the wind. The King tracked well when I brought it up to speed. The bow yawed back and forth only an inch or so, and it was easy for me to hold a straight course. My GPS showed I could slip along at just over 4 knots at a relaxed pace, hold 5 knots if I worked at it, and nudge just over 6 knots in a short sprint. These numbers are good for a sea kayak and just a half knot off my observations for the fastest touring kayaks. It’s not likely the King will be left trailing the pack.

When I took the King out in a 20-knot breeze, whitecaps were everywhere and a few wave crests lapped across the horizon. The boat was nicely balanced in the wind. If the bow strayed, a little edging was enough of a reminder to get it back on course. The King is equipped with neither a skeg nor a rudder, and manages quite well without. The only time the kayak got a bit squirrelly was when I was paddling on the lee side of a low point of land. The waves wrapped around the point, but the wind grazed over it. With the wind and waves coming from different directions and the waves growing short and steep in the shoals, I had to do a lot of steering to hold my course. A skeg or a rudder might have kept the stern from getting pushed around, but I didn’t feel I could fault the King for its performance. It responded well to my prodding to get it back on course. Farther from shore, the wind and waves weren’t so quarrelsome and the King was back on its best behavior.

In a following sea the King was quick to accelerate to surfing speed. If the bow began to drift off the fall line, it was easy enough to correct the course to keep from broaching. When heading upwind the bow had no tendency to bury itself in the oncoming waves, and what little water did come over the bow slipped over the smooth contours of the deck without throwing spray in my face.

Photo by Michael Berman

Photo by Michael BermanRedfish Custom Kayak and Canoe Company has built its reputation on good-performing, well-built boats that stand as works of art. The 17′ 9″ King is a kayak that will take care of a rookie and likewise satisfy a seasoned paddler.

The King is an excellent kayak for rolling. If you think of rolling as a difficult technique that you’d use only in an emergency, the King might just convince you that rolling is something to do for fun. The solid fit of the seating and thigh braces kept me locked solidly in the cockpit, and the Roller’s Recess worked like a charm. Layback rolls were effortless because I could get my torso and head right up against the aft deck.

If you have to bail out of the King after a capsize, you won’t just fall out. To clear the thigh-brace flanges I had to lead one leg ahead of the other. It is important to practice wet exits until they become second nature, and that’s especially true of kayaks with snug-fitting cockpits. After a wet exit I could empty most of the water from the cockpit by swimming to the bow and pushing it up over my head. The cockpit would drain and the King would flop upright with just a bit of water still aboard but not enough to warrant pumping out. The low aft deck made re-entries easy. I could lunge aboard, straddle the kayak, and get into the cockpit seat-first. In flat water I didn’t need to resort to a paddle-float outrigger to stabilize the King for re-entry. Dale’s King didn’t have deck lines to hold a paddle as an outrigger, but they could easily be added.

I managed to get through my sea trials with the King without marring its varnish. While handling such a finely finished boat on land made me tense, the King’s performance on the water put me quite at ease. I’d be happy to paddle a King again, even if it were painted olive drab.

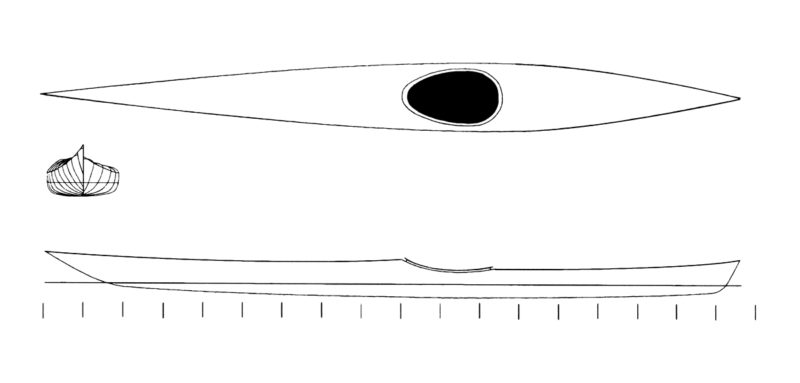

The plans for the King come with full-sized templates for the stems and 16 molds. The 36 pages of instructions are clearly, if sparely written. I suspect what Joe knows about building kayaks could fill a good-sized book. While the color photographs that illustrate the book show several design motifs, Joe leaves the artistic side of the kayak to the builder.

It’s likely that people drawn to a Redfish kayak will fall under the spell of Joe’s artistry. It would be a shame to keep a kayak like the King on carpet-padded racks and away from the grit and gravel that are inevitable in getting a kayak to the water. If you build or buy an eye-catching King, have someone you care for give the varnish its first scratch so you’ll have a pleasant association with the inevitable scars, then get over it and go paddle the damn kayak.

Redfish Kayak specializes in kits and plans for a range of strip-planked paddle craft. The King has plenty of volume for gear stowage, yet is fast and responsive.

Plans and kits are available from Redfish Custom Kayak & Canoe Co. This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2009 and appears here as archival material. If you have more information about this boat, plan or design – please let us know in the comment section.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.