Talk about tough acts to follow! What’s a boatbuilder to do when contemplating the sequel to a model that has long since become a legend in its own time? That’s the question Bill Womack and his crew at Beetle Inc. found themselves asking one day in 2006. Although the Beetle Cat is a big 12′ 4″ boat, it is still a little vessel in which skipper and crew are seated on the cedar floorboards. “What we were after,” said Womack, “was a traditional catboat with seats that would appeal to people who had grown up sailing a Beetle Cat but are now interested in a larger catboat.”

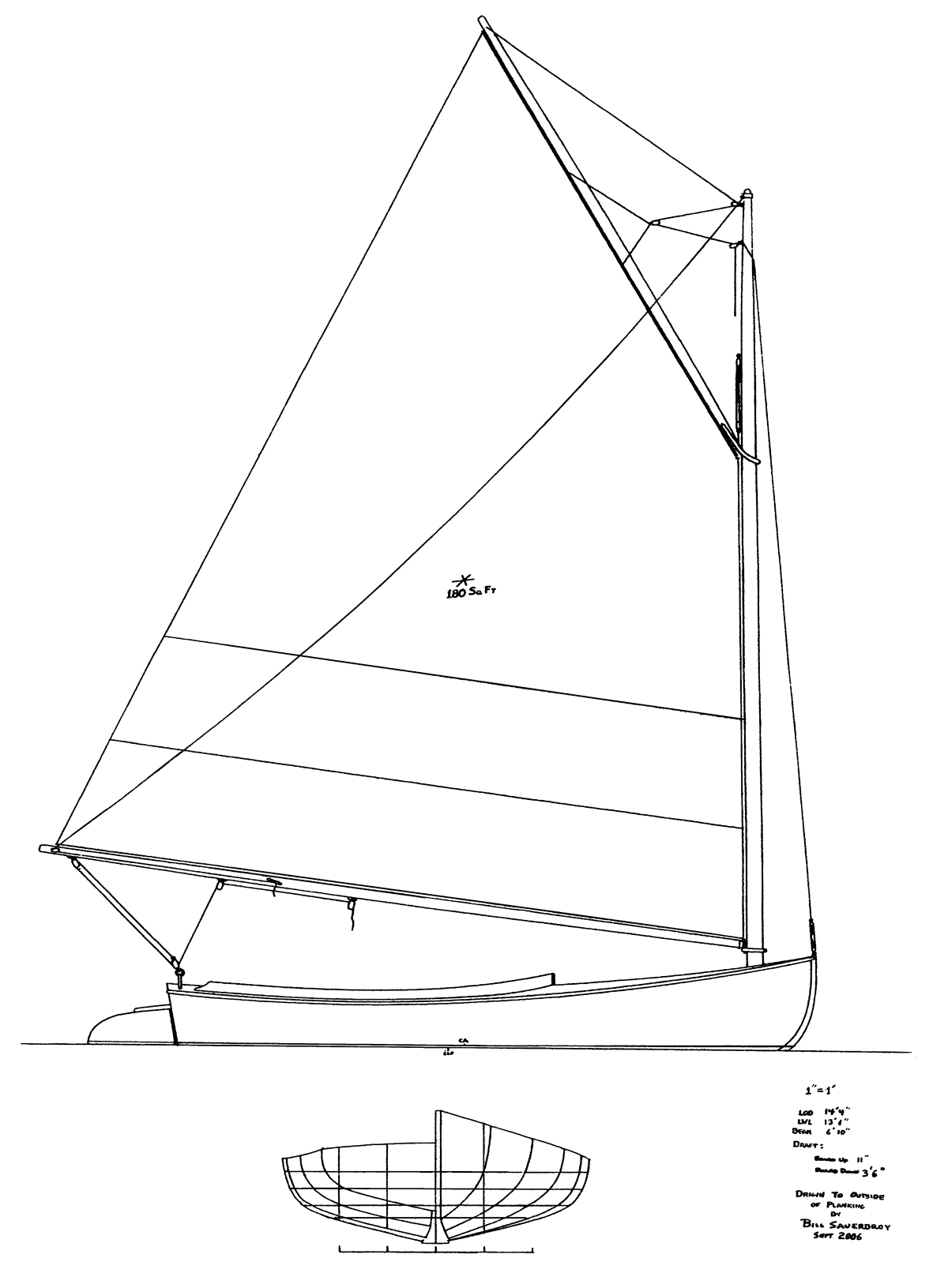

Womack turned the matter over to resident designer-builder for special projects, Bill Sauerbrey. Fresh from his creation of the 28′ C.C. Hanley catboat KATHLEEN (see WB No. 193), Bill soon concluded that a 14′ 4″ hull would be the smallest practical size to gracefully accommodate seats while also being large enough to distinguish itself from the venerable Beetle Cat.

The Beetle 14 (14’4″) is the big sister of the 12′ 4″ classic. Lest you think 2′ is not much of a difference, consider the designer’s observation that “You could fill two [original] Beetles with water and empty them into this boat.” Photo by Stan Grayson

Photo by Stan Grayson

The fact that a catboat has just one sail doesn’t mean there is anything simple about its design. Every proportion and detail, from centerboard location and size to sail cut, must be just right. Sauerbrey is well versed in the technical aspects of yacht design, but he also has a lot of practical experience in how all the various forces react on a centerboard hull powered by a single sail. This first-hand knowledge is a big plus for prospective owners of the Beetle 14. After extensive study of 14′ to 15′ catboats at Mystic Seaport and others for which he found drawings, Sauerbrey emerged with his own variation on the theme. The goal became a design that would avoid extremes and result in a fun-to-sail, solid-feeling yet responsive, and comparatively dry boat.

“The deadrise is more of an everyday catboat than a racing-oriented model,” Sauerbrey noted. “The latter would have a flatter bottom and tighter turn at the bilge. The Beetle 14’s comparatively round bottom is deeper than a Beetle Cat’s and puts more of the rudder in the water. This not only improves steering as the boat heels but means we could round off the rudder. This rudder won’t catch the mainsheet should it be allowed to run out and fall in the water.”

Whatever its shape below the waterline, the Beetle 14 has a distinct resemblance to the Beetle Cat. That’s largely because Sauerbrey used a stem profile similar to that of the smaller boat. Also, the white oak coaming evokes the Beetle Cat’s. The coaming is relatively low, which will make it possible for many sailors to sit on the rail with their feet on the seats and not experience any pressure on the backs of their thighs.

As Sauerbrey worked out the hull shape, he had in mind the practicalities of building as well as performance. “The shape works well in a production setting,” he noted. The frames involve no excessively tight bends, and the hull is built according to the efficient Beetle method with steamed oak frames formed over the mold. That mold now occupies its own production space in Beetle’s Wareham, Massachusetts, shop.

The Beetle 14’s hardware is a mix of Beetle Cat and new pieces custom made to patterns crafted by Sauerbrey. The masthead fitting, eyebolts for blocks, bow chocks, twin mooring cleats, rudder pintles and gudgeons come from the Beetle Cat. The stemhead fitting, mast band/gooseneck, and the optional boom pedestal (or “crab”) are unique to the 14. So is one of the rudder’s tiller straps. The halyard and sheet cleats and the bronze blocks are all one size larger than those of the Beetle Cat. I was impressed with the Beetle 14’s rig. For one thing, the proportions of all the Sitka-spruce spars—mast, gaff, and boom—look exactly right. Nothing is too large or too slender. Rather than design a gaff saddle, some of which work well while others are marginal and unable to resist forces that tilt the gaff to one side or another, Sauerbrey fitted the Beetle 14 gaff with jaws. The boom is rigged with a topping lift, an important feature on any catboat much larger than a Beetle.

Photo by Stan Grayson

Photo by Stan GraysonAs with the original Beetle Cat, the Beetle 14 is carvel planked in cedar on steam-bent white oak frames.

On a sunny day in mid-May, I joined Bill Sauerbrey and his colleague Mark Williams to check out the Beetle 14. We’d be sailing the waters off Osterville, Massachusetts, the very neighborhood in which the Crosby boatshops once stood. A gusty northerly wind had blown all clouds from the sky but suggested that a single reef in the 180-sq-ft sail would be prudent. (The sail has two sets of reefpoints versus the Beetle Cat’s one.)

I stepped gingerly from the dock onto the boat’s bow only to find that the Beetle 14’s foredeck is a very steady platform. Gear is easily stowed under the foredeck where a pair of flotation bags is located for that highly unlikely, “just-in-case” scenario. (The boat carries 500 lbs of lead ballast beneath the floorboards.)

A good way to begin judging a catboat’s functionality is to see if there is anything fussy about hoisting and low- ering the sail. The Beetle 14’s gaff ascended easily. I noted the absence of leathered gaff jaws or parrel beads. Predictably, Sauerbrey had reasons for each. He’s found the gaff balances well, remains perpendicular to the mast, and slides easily thanks to a coating of wax on the jaws. (On the boat we sailed, the mast had remained unmarked after many hoistings and lowerings.) As for parrel beads, there is no need. The hoops hold the sail close enough to the hollow mast that the line around the mast from one jaw to the other is purely a safety measure and pro- duces no friction. The sail, incidentally, comes down very smartly, which is especially reassuring when a boat is sailed on and off its mooring or float (or during reefing procedures).

Photo by Stan Grayson

Photo by Stan GraysonThe Beetle 14 has a hollow spruce mast; the sail is affixed to it via mast hoops. Rather than articulating on a mast-mounted gooseneck, the boom swings on a deck-mounted bronze pedestal.

Underway, the Beetle 14 felt neither overly stiff nor in any way tender. The beamy hull (6’10”) just heels a bit and then forges ahead. There was just the right amount of weather helm, a desirable safety trait that will make the boat want to round up in puffs while giving a pleasant overall steering feel. It was not until we turned for home and began beating up Cotuit Bay that we began to feel some wind-borne spray. Considering the weight of that breeze, the Beetle 14 proved a reasonably dry boat, certainly more so than its smaller sibling. According to Sauerbrey, who has sailed the boat extensively in a wide range of winds, the bow shape helps knock down some spray as the boat heels.

As we headed back to West Bay through the lovely Seapuit River, we found ourselves in the lee of Osterville Grand Island, and Sauerbrey suggested it was time to shake out the reef. He quickly tensioned the topping lift to support the boom, slacked off the clew reef pennant, and uncleated the tack reefing line and then the reef- points. Finally, Bill hoisted the sail to its full height. Now, despite an adverse tide, we tacked our way through the river, raising the foil-sectioned board when it scraped the sand and then lowering away in deeper water. Here was a catboat in its natural habitat, doing its thing to perfection.

As we headed north in West Bay, the wind shifted to the southeast and lost velocity, so we congratulated our- selves on not having to put right back the reef we’d just taken out. All along, I watched how the gaff and boom moved as we shifted from one tack to another. The boom, mounted on the optional pedestal rather than a mast-mounted gooseneck, put no pressure on the mast and both boom and gaff swung easily from port to starboard, creating no uneven strains to mar the sail’s shape.

Photo by Stan Grayson

Photo by Stan GraysonThe Beetle 14’s stern sections and barn-door rudder are reminiscent of the original Beetle Cat; the seats, visible here, aren’t (sailing an original Beetle, skipper and crew sit directly on the cockpit sole).

The battenless “Egyptian cream cloth” sail was developed by Bill Ribar—it seems almost everyone in this project was named Bill—of Doyle Buzzards Bay; he has extensive gaff rig experience. The sail is notably well reinforced at all corners and the tack and clew reef cringles. It was very responsive to tinkering with halyard tension on different points of sail. According to Ribar, the sail has a little less fullness than a Beetle Cat’s in order to enhance pointing ability. Whether one chooses to order this sailor talk to another sailmaker experienced in the ways of gaff rig, be advised that you get what you pay for in a sail. A well-designed sail built of quality fabric will hold its shape long after cheaper versions have broken down.

One sometimes hears the term “wholesome” used in regards to a sailboat. My overall impression is that the “wholesome” adjective perfectly fits the Beetle 14. This is an honest boat that is fun, rewarding, safe, good to look at, and small enough to be built of now scarce classic materials (a white oak keel, 5⁄8″ Atlantic white cedar planks over white oak frames, with domestically made bronze fastenings). Neither is the boat so big as to present a maintenance headache. The topsides are coated with an easily sanded Pettit semigloss, while earth-toned Kirby flat finish colors are used on deck canvas and the interior. Sauerbrey noted that the interior paint will age gracefully and can be maintained with light sanding and an occasional thin recoating. About the only thing I could think to add to the Beetle 14 might be a mast coat—Sauerbrey didn’t rule this out but noted that, without one, water is not trapped at the mast partner but instead passes freely into the bilge—and some cushions.

For those fortunate to live in an area of shoal waters and sandy bottoms, the Beetle 14 should provide many years of satisfying ownership. The $35,500 price is certainly competitive for a professionally built boat of 1,250 lbs displacement. The buyer of the first boat, seeking something with more comfort than his Beetle Cat and more liveliness than his centerboard sloop, liked his Beetle 14 so much that he ordered another.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2009; learn more from Beetle Inc.

I absolutely loved all of the references to past catboats. Now, what would a version of similar size concocted from the work of Gil Smith look like? For sure, it would be sweeter looking. Ball in your court.

It would be nice to add an interior picture. I wonder about sleeping aboard under a boom tent.