MARCUS NOER is a particularly fine example of a traditional double-ender from Denmark, with a shapeliness to her hull that will take your breath away. The design is one descendant—one of many—of a Nordic boatbuilding tradition that should properly stand beside the great cathedrals of the world and the sculptures of antiquity as among the loveliest creations ever made by man.

This design is not for beginners. It is, however, absolutely a design that any beginner should aspire to, in my view. A boatbuilder young in experience should choose a much simpler boat first, or maybe a succession of two or three, perhaps working with other builders or taking one of a number of specialized classes before attempting such a boat. But as he does so, he should know that each saw cut made straight and true and each plank line sweeping an honest curve will contribute to the understanding of something greater. Each boat built should contribute to the understanding for the next boat.

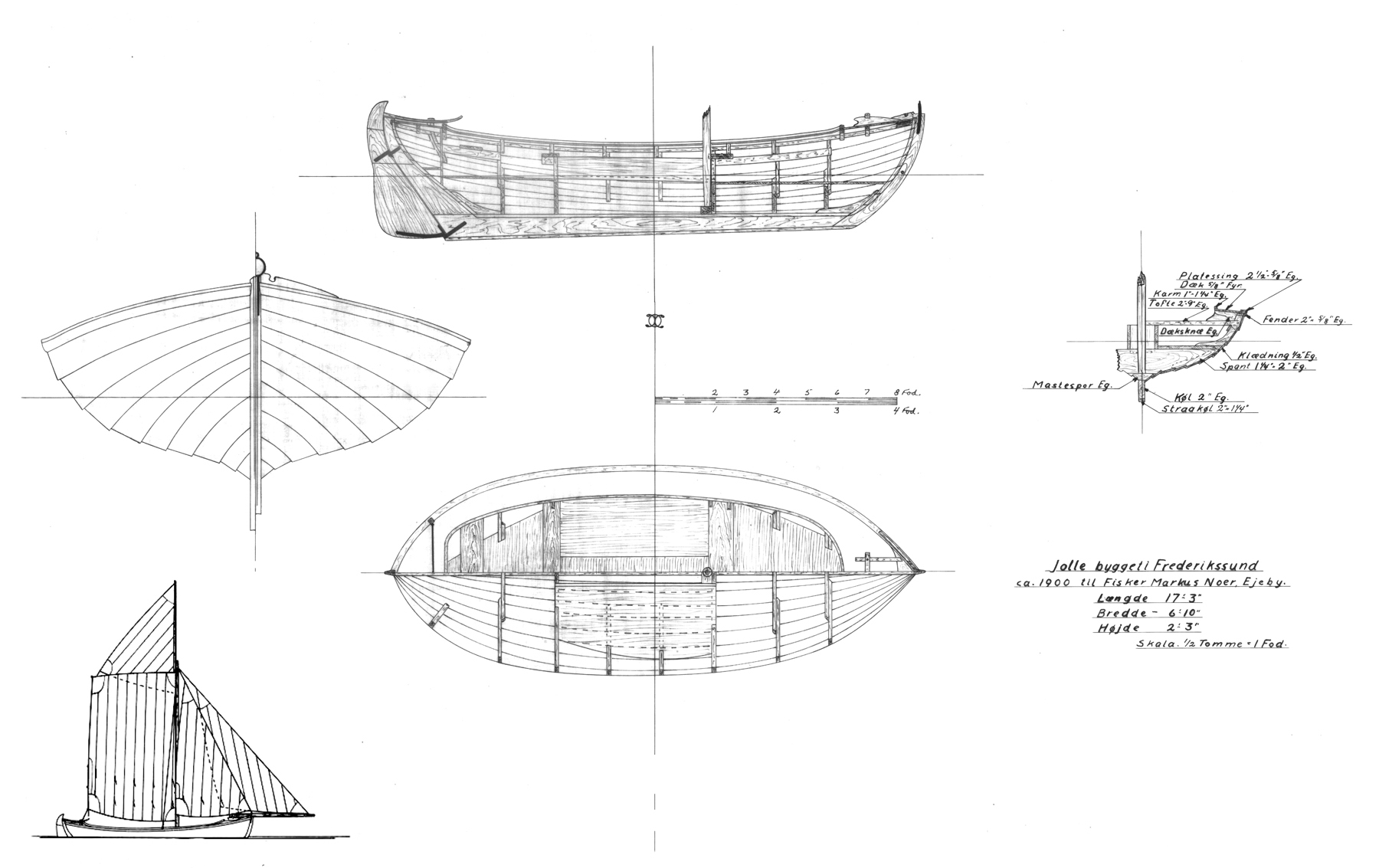

This 17′ 81⁄2″ lapstrake-planked double-ender can stand comparison to the finest of yacht design, and yet this hull comes down to us from an everyday craftsman for a common fisherman. The original “jolle” was built in Frederikssund in 1900 for one Marcus Noer of Ejby, in Isefjord, Denmark. His catch, sole, and flounder, was kept alive in a wet well, essentially a box built into the hull, which had holes bored in the planking to allow water to fill the box. This replica, built in 1980, is faithful to the original design and all-oak construction—with the exception of refraining from boring holes in the planking.

Photo by Tom Jackson

Photo by Tom JacksonThe lovely curves of a traditional Danish Frederikssund jolle are accentuated by the lapstrake planking lines.

MARCUS NOER is one of the boats in the collections of the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde. This museum, which is in a mid-sized town about an hour’s train ride west of Copenhagen, is noted for its archaeology and its exacting replica constructions, but it also has amassed an impressive collection of small craft, several of which would be excellent examples of boats for home builders. These boats inherit and share characteristics that came down remarkably unchanged from Viking times. The museum boatyard’s purpose is to preserve traditional skills in addition to the boats themselves.

Anyone who doesn’t want to take the time—which would be considerable—to build one of these boats can have one custom-built, and not just MARCUS NOER. Want an exact replica of the faering, or four-oared boat, that was recovered with the famous Gokstad Viking ship in the 1880s? The museum boatshop can build one. Among the small-craft collections, any number of boats would be likely candidates, but for me, MARCUS NOER has that “just right” feel. I see that I’m not alone in this, because when I was at the museum in May 2008, two of these Frederikssund boats were on the pier, newly constructed for private clients and ready for shipping. Inside, a similar type called a Lyneasjolle was days away from launching, and an ancient-looking faering was in for restoration.

Søren Nielsen, the boatshop director, says that he builds the boats right-side-up over molds. “Traditionally, that was, as you know, not the way to do it,” he says. “Our plan is, however, after we have built a few more of these boats, to throw the molds away and build them ‘as in the old days’—without molds but with a few measurements in the right places. You just have to have some experience before you do that, because you have to know exactly where the important measure has to be taken to build a good boat.” The boat’s rounded stern presents challenges even for experienced builders.

The interpretation of the Frederikssund jolle plans would be a challenge in its own right. For openers, the particulars are typically reported in metric measurements, but the plans sheets themselves, drawn by historian Christian Nielsen in the 20th century, are in feet and inches. However, if you do the calculations, you’ll see that the translation doesn’t quite work out. Take the overall length as an example: 5.4 meters equals about 17′ 81⁄2″. But on the plans sheets—which were completed before Denmark adopted the metric system—the length is clearly shown as 17′ 3″. Why the difference? The answer is that the Danish inch was historically a little longer than the English inch—26.17mm instead of 25.4mm. (There’s one more reason the metric system took hold!) Just interpreting the plans sheet will involve some understanding of the history of changing measurement systems and will call for judgment on the part of the builder.

Photo by Tom Jackson

Photo by Tom JacksonThe boatshop at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark, builds boats for clients, and two Frederikssund jolles just like MARCUS NOER, built almost entirely of oak and newly oiled, were among the boats constructed in 2008.

The plans are available on a CD supplement to a book published by the Danish Maritime Museum; getting them onto a plans sheet that would be useful might involve a trip to a printing or engineering office that has a large printer. (Here at WoodenBoat, we had trouble opening the CD in a Macintosh computer.) In the end, redrawing the plans to a chosen scale may be the best way to go and will significantly ease the task of lofting the plans out full-scale, which will be essential in any event. Builders will also notice that these plans do not have an accompanying table of offsets, that list of all-important measurements—or at least if they ever did, they haven’t survived. From redrawn plans, the builder might be well advised to develop his own table of offsets before lofting.

Sourcing materials could also be difficult. White oak planking, which is the traditional choice, would be excellent because it steam-bends so beautifully. Where white oak is scarce, finding adequate stock would be difficult or expensive. But larch and pine also have been used to good effect. For the backbone timbers, any good structural wood—superior Douglas-fir, say, or purpleheart, or angelique—would do nicely.

The builder willing to accept up-front complexity will be rewarded later by the simplicity of the boat’s setup. With a couple of exceptions, fitting out would be simple. There are no complicated systems. The jibsheet fairleads are the simplest imaginable, hewn of wood. Other than copper rivets, the boat uses very little metal, and the original fittings were meant to be simple and inexpensive. The museum boatbuilders use galvanized steel fittings for the two complex metal pieces (the exceptions mentioned above): the stemhead fitting and the rudder gear. Galvanized steel won’t last nearly as long as bronze, but it’s in keeping with the ways of the original boats. Of course, with the price of copper and bronze heading for the stratosphere these days, maybe it’s time to leave off this demand for bronze in every instance and think seriously about a return to galvanized ferrous metals for certain kinds of boats. Not every boat has to be a yacht.

The finish on this boat is equally simple: a 50:50 blend of pine tar and raw linseed oil. The mix stays tacky for a while, hardening in a few weeks, especially in the sun. It turns the wood black as can be, but on this boat that just seems natural and right. The entire interior, the spars, and the topsides are all finished this way. The only paint on the boat is bottom antifouling.

This boat is heavy, at about 1,984 lbs, with a very deep keel—what the Danes call a “high” keel. Getting the boat on and off a trailer would be difficult, but doable: the museum tows the boat to various festivals, near and far. But launching off a trailer isn’t something you’d want to do every day. Paying a yard to haul the boat with a Travelift would make easy work of it, but the fact is that this boat would be happiest in a marina or at a mooring.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. That heavy old fish boat, oh, my God, she’s going to sail like a slug. You’ll have to get an oar out to work her around every time you tack, and while all your friends with super-lightweight plywood-epoxy craft are out there on the beach finishing off their lunch, you’ll still be back in harbor trying to tack your way clear.

Think again. She’s an amazingly sprightly sailer and a joy to handle. She comes about like a dinghy, with a light touch on the tiller. The jibs have to be backed briefly, but the boat comes about cleanly and with little fuss. She picks up speed right away on the new tack. Her topsail sets and strikes easily, with no specialized gear. The snotter—that sling that holds the heel of the sprit—is held by friction alone, so adjustment is dead easy: push the sprit heel up to gain some slack, then slide the snotter wherever you want it to increase or decrease sail tension.

Photos by Tom Jackson

Photos by Tom JacksonLeft—Tholepin rowing, combined with a simple shroud tie-down and a wooden jibsheet fairlead, show the simplicity of MARCUS NOER’s fittings. Right—Hemp rope has such good friction that no mast fittings are needed to set the snotter line, a sling holding the heel of the sprit.

I sailed MARCUS NOER on a cloudy day with moderate breezes off Roskilde with Dylan Coils, a New Zealander who has worked at the Viking Ship Museum as a sailing teacher for years, and with Max Vinner, a retired curator. Max never tired of sailing MARCUS NOER, which for his many years at the museum remained his boat of choice for singlehanded daysailing after work.

With her broad hull, MARCUS NOER is stable and powerful. The very broad side decks give her the equivalent of a great deal of freeboard, and yet her sheerline is low, originally to give the fisherman easier work in hauling his catch. Those side decks give the crew a very comfortable seat when the breeze requires a bit of weight on the weather rail. With both jibs and her topsail flying, all set with the simplest of gear, she takes the wind like a stallion. We would not expect her to point to weather like a modern racing yacht, and yet her windward abilities would come as a serious surprise to racing sailors.

Ashore, her rig is easily handled. The time-honored way to furl the sprit mainsail is to remove the sprit heel from the snotter, sway it aft until it is parallel with the mast, and then, starting with the leech, roll the sail up in the sprit like a carpet until it comes right up to the mast. A simple length of line binds it all together neatly. The topsail rolls on its spar, too, and that bundle fits inside the cockpit. All very simple, with a minimum of fittings. There are lessons in these workings for boatbuilders of any kind.

At the time I sailed MARCUS NOER, I was in that odd position of being simultaneously almost finished with one boat and just on the cusp of looking around for what might be next—after a respectable interval of time for house projects, of course. I suspect that for my next boat I’ll look no further than MARCUS NOER.

Among us there are some—and perhaps, quietly, many—for whom the number of boats built, measured in total or over a given period of time, is of no consequence. We may be professional in other things, but not in this. At the end of the day (to take a weary cliché back to its original meaning), we hang measurable outcomes and paradigm shifts on hooks alongside our hats and coats. In our own workshops, we work a piece until it pleases the eye and feels good in the hand, and for this one part of our lives that is our only unit of time. To those who prefer to work in this way, the only boat design that makes any sense is one that makes our hearts yearn. This Frederikssund jolle is such a boat.![]()

The Frederikssund jolle was documented at a time when Danish inches were still in use; therefore, interpreting the lines and construction plans will pose some challenges. For a motivated person with some experience, the result will be worth the effort.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2009 and appears here as archival material. If you have more information about this boat, plan or design – please let us know in the comment section.

Wow! What a beautiful boat! Thanks for publishing this. I’ve seen this or a very similar design in Christian Nielsen’s book about Danish boats, Wooden Boat Designs. It looks very difficult to build, and it would be nearly impossible to find good materials here in South-Central Alaska, where we only have so-so white spruce. Perhaps some of those wide, yellow-cedar boards from SE Alaska? Fun to dream; so many boats, so little time….

The Viking Boat Museum at Roskilde is a must visit. Paid to sail one of their boats and ended up at the helm. What a fun time everyone had!

It’s a boat that makes me really want it. Just looking at the picture, I can feel the sensibility of the wooden boat. Thank you for this article.

What a boat. You describe plans in the article. Was wondering where you can get a set of plans or the CD that you mention. It would be a fun exercise to study the drawings or plans and run them past one of the local wooden boat shops here in NS. Any info would be greatly appreciated. Thank you.

CH

A comment concerning metals: Galvanized cast iron seems to hold up for a long time. At one time I had a cruiser converted from a pre-WW II whaleboat that came with a big galvanized bit on the after deck. It had been exposed to all kinds of weather for years, as well as abrasion from hemp mooring lines, etc. It showed no signs of rust or corrosion.

I also owned for 18 years a little 21′ cutter (an Ed Monk Sr. design) built in 1935. It was fastened with galvanized-iron boat nails. One time I decided to pluck out a planking nail (from below the water line) to see if I might need to refasten. I ground a long-nosed Vice Grip to enable pulling a nail, which was very solidly planted in the oak frame. To my surprise, the nail was in perfect condition, showing no signs of rust or corrosion whatsoever, though it was stained brown,I assume from the tannic acid in the oak frame.

But I have my doubts about galvanized steel, since steel seems to rust much more easily than iron. Perhaps if the steel had been hot-dipped, there wouldn’t be a problem, though. I’m curious what others think about this, especially if they can cite either personal experience or expert knowledge.

Hi,

Where can I get some plans for this boat?

Many thanks

I’m left wanting to see a photo of her with all her sails in 12+