In 1901, Thomas Fleming Day, who founded The Rudder a decade earlier, conceived a boat that would bring ocean voyaging to the common man. Simple enough to be built by amateurs, small enough to be singlehanded, and big enough for long passages, the Sea Bird yawl still beckons those with a sense of adventure.

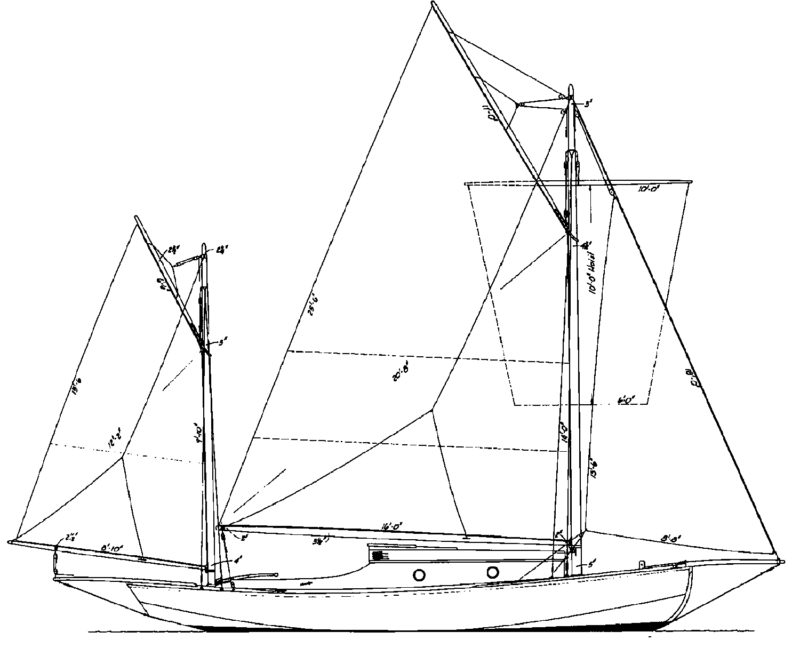

She was originally a centerboarder, but Day soon added a deep keel for ocean passages, including an Atlantic crossing he made in 1911. With The Rudder’s publicity, plans, and instructions, the design soon caught hold. Hundreds have been built. Day’s vision turned out to be unusually lovely for a hard-chined hull, in plans formalized by C.D. Mower and Larry Huntington. Boats of this type have cross-sectional shape consisting of nearly straight lines rather than the svelte curves of racing craft. Sea Bird’s sweeping chine curve rises high forward and aft and just kisses the waterline amidships. The shape is complemented by her gaff-headed yawl rig. In 1981 WoodenBoat, working with Mystic Seaport, had the plans redrawn by Dave Dillion (see WB No. 43), and the seven-sheet set of plans, which includes the deep-keel option, is still available through The WoodenBoat Store.

Joel Page

Joel PageAt 25’ 7 1⁄2” overall, the centerboard version of the Sea Bird can—with effort—take to the water each spring from a launching ramp, with her 1,300 lbs of ballast added later.

I first saw a Sea Bird in a photograph published in a book I’ve long forgotten. Taken from astern in a calm harbor, the picture captured the distinctive transom, which was intriguing to draw and immediately made me imagine building the boat. Some years ago, sailing into Robinhood Cove, Maine, I saw a boat that instantly brought me right back to that photo. She had a rightness about her. This particularly fine Sea Bird, I learned, was built by Alex Hadden in nearby Georgetown.

Hadden launched his centerboarder in 1988. He had come by a marconi rig complete with masts, sails, rigging, and hardware, from a Sea Bird that had been cut up, and he planned to build the boat for sale. The project launched Hadden’s business, but not the way he intended: somebody with an aged Sea Bird hired him for a reconstruction instead. It was his first commission, but he ended up keeping the boat he hoped would be his first sale.

After sailing the boat for years, Hadden has concluded that his 361-sq-ft marconi rig (which is not included in the plans set) would be best suited to the deep-keel version, and the original gaff rig, with its 383 sq ft of area but a lower heeling moment, would be a better fit for the original centerboard version. He compensated for the marconi-centerboard combination by using 1,300 lbs instead of 1,000 lbs of internal lead ballast to keep her on her feet. He has considered changing to gaff rig but loves the simplicity of the triangular sails.

Joel Page

Joel PageHadden has devised A-frame sheer legs for stepping his masts before launching.

There’s that word again: simplicity. If Hadden has learned one thing about the Sea Bird in more than two decades, it is to make things ever simpler. During a recent deck replacement, he eliminated both a large bridge-deck hatch and a foredeck hatch. He removed his built-in VHF radio, together with its masthead antenna and wires, in favor of a handheld model. His red and green side lights are fitted into shroud-mounted blinds that take a little time to reinstall every year, but “It’s less obtrusive than pretty much anywhere else I can think to put them. And they work better up there, if you’re actually out sailing at night.

“The whole effort was to make it as simple and easy to paint as possible, because that’s all I do is paint,” Hadden said. He has strived to remove deck fittings. “If it’s not absolutely necessary, I don’t want to even look at it. You’re either sanding or you’re reminded of when you were sanding.”

The Sea Bird seems to scream it like a gull’s cry: Simplify, simplify. It’s a good antidote to life’s increasing complications.

Hadden launches his boat each year from a trailer, which is very unusual for a 25′ 7 1⁄2″ LOA boat that displaces some 6,000 lbs. It takes some effort. For example, he raises the rig while still ashore, and his bread-pan-sized lead ballast castings have to be transferred to the boat by skiff, one at a time, in what has become an annual ritual. But he pays nothing for haulage. He has the vast satisfaction of independence.

Having a deep keel would free up cabin space, true, but at a price: “There goes your hauling out on the trailer. There goes going happily wherever you want without navigating, which I enjoy. I can explore, and you really don’t have to worry, you’re just going to hit the centerboard.” He once poled the boat up a creek too narrow to turn around in, and next morning poled her out stern-first. He tells me this as we sail within what seems an arm’s reach of the cove’s rocky shore. “You wouldn’t be doing this if you converted this to a keel boat.”

Jonathan Taggart

Jonathan TaggartWith low freeboard, a proportional low-profile cabin trunk has everything to do with the Sea Bird’s appearance and also its function, giving the helmsman a clear view forward.

In the light and fluky breeze, she responded well to occasional puffs. She answered the tiller easily, with the feel of a larger boat. She tacks easily. Hadden has made only one change to the rigging: he brought the jibsheets inboard of the cockpit coaming instead of making them off to cleats on their outboard faces. “I brazenly cut holes in the coaming, just so when you are heeled over you can control that from the inside.” She ghosted along, only surrendering when the ebb made it clear that the current, and not the wind, was in control that afternoon. The Yanmar diesel carried us the last few hundred yards to the mooring.

“My favorite times are when it’s kind of dreary out, windy, and you’re going through the chop and the waves are hitting the bottom of the jib and streaming down,” Hadden says. “That’s when I’m saying to myself, ‘Okay, this is like the paintings.’” She handles best in about 15 knots of wind. Her mizzen is fairly large for a yawl, so it gets reefed first. In high winds, Hadden douses the jib and mizzen and sails on a reefed main alone.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonSpartan accommodations encourage a simplicity of lifestyle that matches the boat’s overall theme.

The boat doesn’t pound in waves, and Hadden has actually found advantages in the hard chines. “People say, ‘Oh, it’s a hard chine,’ and that’s one of the reasons I think people don’t bother with it. But this particular boat, if you got rid of the chines, you’d lose it. That’s the best thing about it, is the chine line, the shape it makes. If you rounded that, it’d be fine, probably, but you’d lose a lot of the look. But when it gets rough out, t’s throwing the waves and all the water off to leeward. It’s a great thing.”

Hadden used 1″ Atlantic white cedar planking over oak backbone timbers and frames. “Structurally, these sawn frames are great. They’ve got big screws in them, they’re really deep, there’s a lot of them. I can’t imagine anything falling apart.” After it takes up, the hull does not leak. His original deck did, though, because the tongue-and-groove pine moved a lot and cracked the paint of the canvas. He replaced it with plywood sheathed in Dynel set in epoxy to better keep the water out. He couldn’t bear, however, to part with the traditional canvas sheathing over his coach roof, which fared much better because it was planked in fine cedar.

Jonathan Taggart

Jonathan TaggartThe bridge deck provides comfortable seating and makes the cockpit a sociable size.

Some Sea Bird builders made unfortunate design changes, especially involving the trunk cabin. For Hadden, even his new deck altered the purity of the boat’s profile perceptibly. “This is only a quarter of an inch lower, but I can tell the difference when I sit there in the window and look out at it. It’s not much. I got over it. But people who haven’t done it much, they’re always going, ‘Oh, who’s going to see an inch, inch and a half, two inches.’ So in the Sea Birds, a lot of them, the cabins were inches higher and wider.” Some extended the cabin aft, eliminating the bridge deck and with it the most comfortable place to sit topsides. Some clumsily squared off the cabin and used oversized portlights. Some changes were more drastic: “In the one we rebuilt, the stem was plumb, and had a big knuckle. The boat’s not drawn anything like that.”

The cabin, dominated by the centerboard trunk, provides rudimentary shelter, not comfort. In reality, it isn’t any smaller than those of many other small cruisers, a type that invites clever and inventive tinkering.

For example, because the chine knees intrude into the bench seats, Hadden fitted removable boards between the seat edges and trunk sides to make more comfortable sleeping platforms. Like many builders, Hadden is rife with ideas for greater interior comfort and practicality. But he mostly takes short trips these days, so those cruising solutions can wait. For now, he’s content to simply sail, just the way Thomas Fleming Day imagined it all.![]()

Plans for the Sea Bird yawl are available from WoodenBoat Store, and Hadden Boat Company.

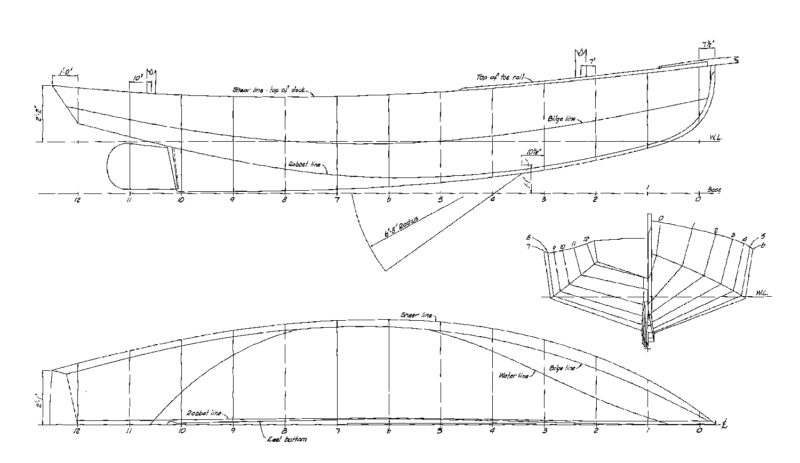

Dave Dillon/WoodenBoat

Dave Dillon/WoodenBoatThomas Fleming Day had ease of construction and limited expense in mind when he conceived the hard-chined Sea Bird yawl, yet the centerboarder proved herself in 1,000 miles of cruising in her first season in 1902. Redrawn by Dave Dillion for WoodenBoat in 1981 to rejuvenate interest in the type, the plans include the original gaff-rigged mainsail and ample detail for amateur construction.

Sea Bird Particulars: LOA 25′ 7 ½”, LWL 20′, Beam 8′ 1 ½”, Draft, board up 4′, Draft, board down 1′ 11″, Sail area (original gaff rig) 383 sq ft, Ballast (internal) 1000+ lbs, Displacement ~6000 lbs

My uncle, Harry Pidgeon, built and sailed the most important Seabird yawl. It was named ISLANDER and he was the first to sail around the world alone twice. He was on his third when he was shipwrecked by a storm in the New Hebrides.

Nice story your uncle shared of his time doing it as well.

Great to hear from you, Bill. I hope you might have seen Eric Vibart’s article in WoodenBoat No. 206 (January/February 2009) about Harry. He must have been a fascinating character!

What a great article about the Sea Bird. Eric Vibart wrote an article about my Sea Bird Yawl L’ESPILL DEL MAR in 2011 for the magazine Voiles et Voiliers.

Harry was a distant relative of mine too; funny to think of all those years sailing down in San Pedro where he built Islander.

Loved your uncle’s book and have sailed by Terminal Island many times, often thinking of the place it was when he built the boat. His attitude and general demeanor proves again that people everywhere respond in kind to the travelers who pass through.

There was a larger Sea Bird yawl in Marblehead, Massachusetts, named SPAR HAWK which had 4 berths, head forward with trunk cabin overhead hatch when open one could stand while peeing. SPAR HAWK was 30′ on deck.

Sweet sailing boat in the ’50s and ’60s.

My step grandfather Jon Brundage had a Sea Bird yawl named SEA BIRD in slip #2 at the St. Francis Yacht Club on San Francisco Bay from the 1930s all the way to his passing in 1982. It is the boat I learned to sail on in the Bay. It was great to read this story and brought back fond memories of summer afternoons and evenings. He single-handed to Catalina and Mexico many times. His estate sold the boat and I was unable to purchase it at the time. I have no idea where it ended up. Glad there is still a following and plans available.

I believe my great grandfather may have owned the Seabird that those Marconi spars came off of, the timeline lines up being cut up right about perfectly 1988 or so and the rigs look identical.

Where was your great grandfather’s Sea Bird? I have a vague idea of how I ended up with those spars. Let me know…

Excellent article about a fine old boat. One would think though that if one were after simplicity and authenticity that the first thing to do would be to jettison the engine. I cannot understand how any boat can be expected to sail dragging a fixed, three-bladed prop around. Without the prop and aperture you likely would have been able to return to her mooring under sail. A further benefit: getting rid of an inboard engine and its associated gear and you have instantly cut maintenance time and cost in half, something that should have particular appeal to owners of traditionally-built wooden boats.

Simple enough for Amateurs? Chapelle writes: If the chine comes up high on the stem spend time in the moaning chair. He also writes in the design book the chine should join the stem near the water line. My boat only took 500 bs lead to float on the designed WL. She is in Wychmere Harbor, Harwich Port, every summer since ’85 and needs a new owner.

Michael

Does she still need a new owner?

I grew up in the NYC area. My father purchased a delapadated 30″ Seabird yawl GULL. I spent my high-school years helping refurbish her and sailing between western Long Island Sound and Maine. I am a landlocked Coloradoan now, but those memories of weathering calms, storms, groundings, dismastings, whales, hurricanes, and more are priceless. GULL now calls home Deer Isle Maine, with my brother.