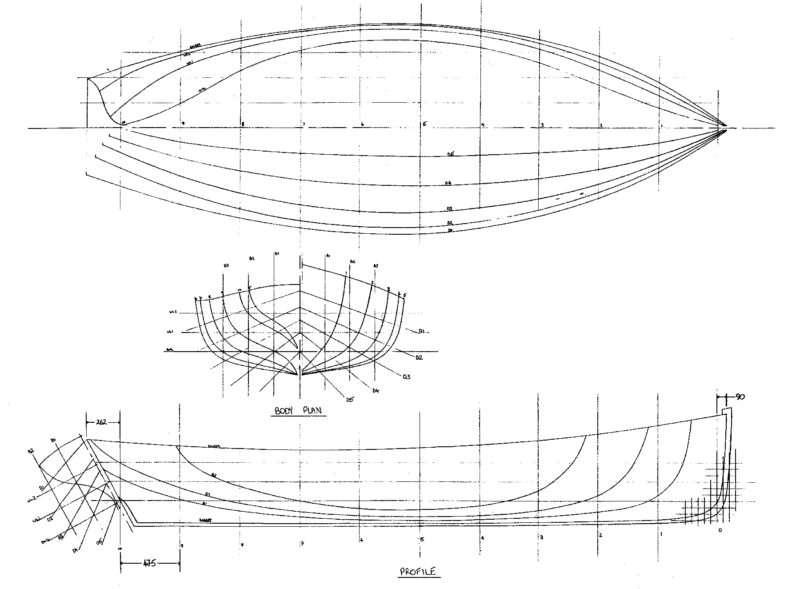

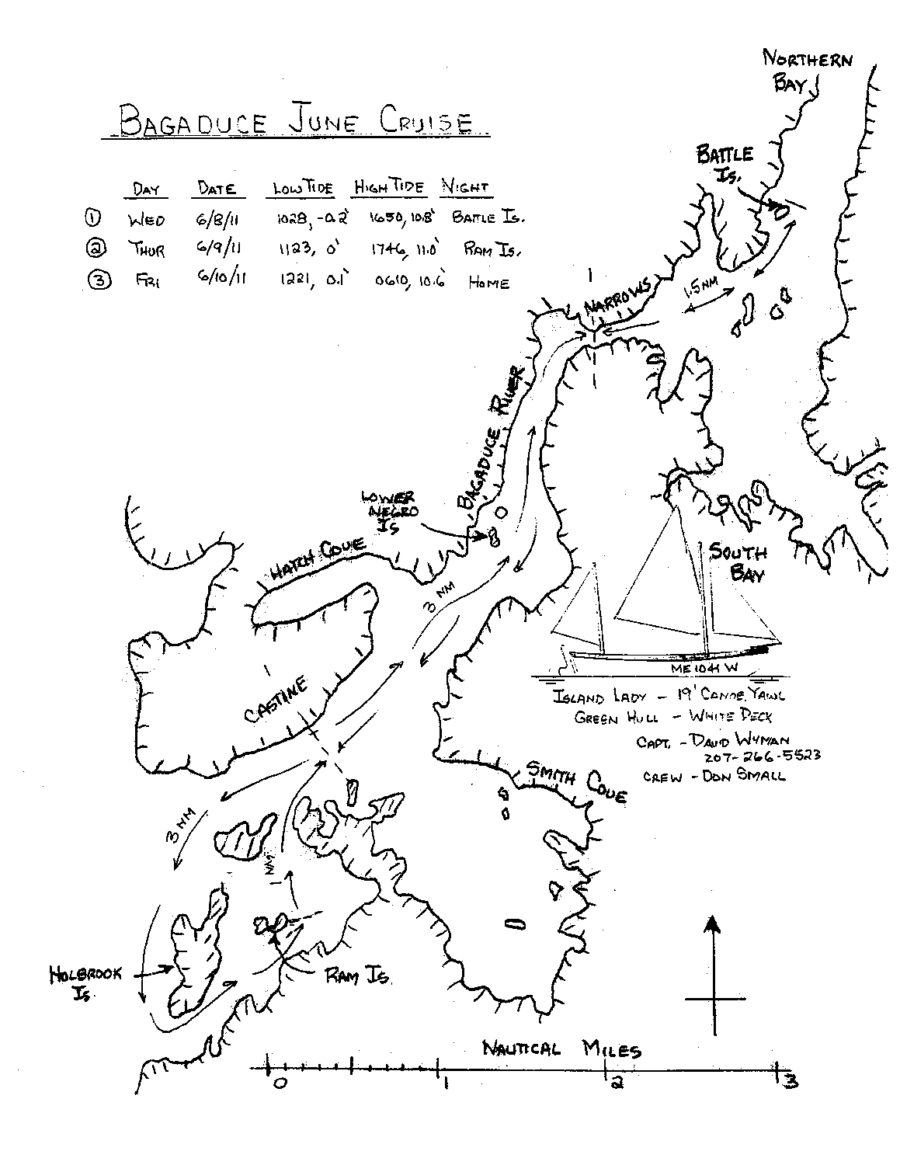

The Salty Heaven is a 17′ by 5′ 9″ cat-yawl intended for day-sailing and camp-cruising. Her Australian designer, Mikey Floyd, is an admirer of traditional working boats, which used to go about their business using a minimum of fancy gadgetry. There are only four strings to pull: two halyards and two sheets. Roll her off the trailer, erect the two unstayed masts, slide the boomkin and rudder into place, hoist sail, and you’ll be on the move within 15 minutes.

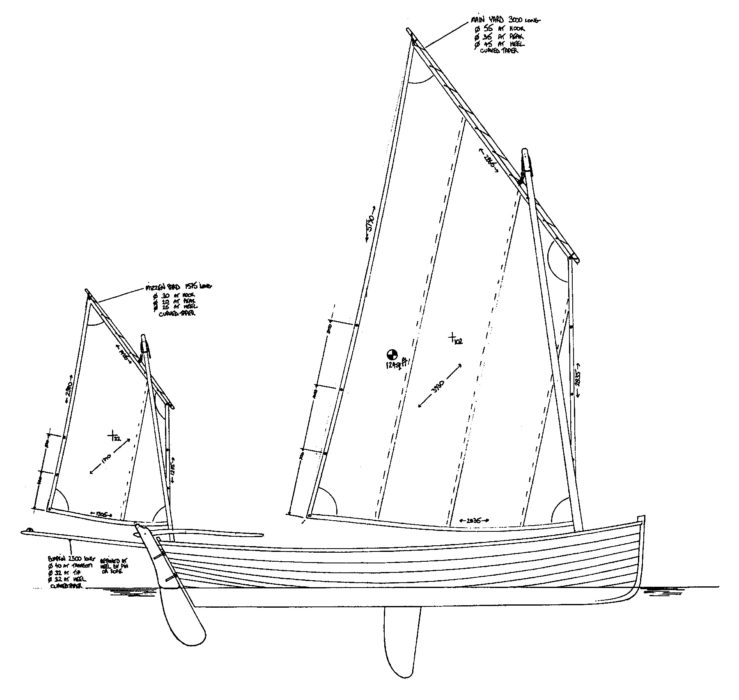

The sails are standing lugs, a rig which has proved itself over centuries in working boats, where trouble-free practicality is a commercial imperative. They are carried without booms, which has pluses and minuses. On the plus side, there’s nothing solid to beat passengers over the head during maneuvers. You still need to be careful of the blocks attached to the clew of the main-sail, but their positioning is such that they are generally out of the way of both skipper and crew. Advocates for booms point out that you cannot run directly downwind without them. Indeed, if you try, you risk the dreaded death roll, which on a boat that can capsize is to be avoided at all costs. On a Salty Heaven, you make your way downwind in a series of broad reaches—so-called “tacking downwind.” Modern racing boats often adopt the same tactic; you sail farther, but you get there faster.

A Salty Heaven looks old-fashioned, with a straight stem and a nice sheer terminating at a pretty wineglass transom. Her raked masts give her an air of elegance and purpose. This boat would not have seemed out of place drawn up on the beach beside an English fishing village a century ago. But, look closely: Her lapped marine plywood planks are fastened with glue rather than nails and roves. In fact, thanks to the wonders of epoxy, there are hardly any mechanical fastenings in the entire boat.

Paul Boocock

Paul BoocockAfter reefing, a simple toggle-and-eye makes reattaching the sheet easy. Note rope-stropped block; hardware is kept to the minimum.

Mikey Floyd designed the first Salty Heaven 11 years ago for himself. After a lot of use in a wide range of conditions, subsequent plans were slightly altered. The planking size was beefed up from 1⁄4″ to 3⁄8″, and the seven frames now run from gunwale to gunwale. Previously they were more like extended floor timbers. The original boat had a separate skeg. Subsequent boats are planked down to the heel. The original daggerboard was replaced by a pivoting centerboard.

In keeping with the designer’s wish to keep things simple, there are few bolt-on fittings. Fairleads are fashioned from hardwood. The halyards are made fast on wooden belaying pins, held in place by Turk’s heads. To link the tiller to its extension, a piece of line is passed through the tiller and led to a hole in the end of the extension. It is then knotted at both ends. Even the sheaves in the wood-shell blocks are made from hardwood. The bronze rudder fittings and the oarlocks are the only manufactured items. Of course, a home builder could use more off-the-shelf fittings if desired.

You may suppose that all this old-fashioned technology makes for a clunky sailer, but this is not so. I’ve owned my Salty Heaven, JESS, for nine years and the more I sail her, the more I appreciate her qualities (see WoodenBoat No. 176). She will move in a zephyr and, provided you rig her to suit, she will keep on sailing in up to 30 knots of wind. The first reef goes in at about 15 knots, the second at 20, and the third at 25. If things get desperate there are two rows of reefs in the mizzen as well. Sailing in 30 knots is not recommended in an open boat, but if necessary it is possible. I carry two canvas bags that I can fill with sand to augment the 110 lbs of lead ballast permanently installed. No matter what the conditions, the boat remains well balanced and manageable.

Paul Boocock

Paul BoocockHalyards are made fast to wooden belaying pins. Fairleads and the grommet in the tack of the sail (not shown) are also wooden.

As with any open boat, you need to reef in good time and to be constantly alert when it’s blowing hard. Once or twice when I’ve been lazy about reefing, I’ve dipped the rail and shipped a few bucket loads of water. With the mainsheet started, the little mizzen screws the boat around head-to-wind where she waits patiently while her foolish owner bails her out. The design calls for two blocks of foam buoyancy strapped underneath the side seats. Testing these in a deliberate capsize, Floyd confirmed that the boat will float with the top of the centerboard trunk clear of the water.

Going downwind it’s a good idea to raise the centerboard so that the boat will not trip. Once or twice on a hard reach, again with a bit too much sail up, JESS has been on the verge of being overpowered. The trick is to bear away. The boat heels, then skids sideways for a moment or two before the hard turn of the bilge pushes her back on an even keel. During these somewhat nerve-wracking moments, she maintains fingertip control.

Paul Boocock

Paul BoocockDesigner Mikey Floyd sailing his original SALTY HEAVEN on Pittwater, Sydney, Australia.

In practice, these boats are so forgiving that it would require a catastrophic situation for a complete capsize. Sailed conservatively, Salty Heavens are stable and predictable. I should mention, though, that the crew can get a wet ride going to weather, from spray thrown back over the windward side of the boat.

Salty Heavens are a lot of fun to sail singlehanded. True to their workboat heritage, they are also willing load carriers. Four (or, at a pinch, six) passengers or a big load of camping gear are no problem. In fact, the boat seems to like the extra weight.

The designed draft is 8″. With the centerboard and rudder pivoted into the raised position, you can skim through the shallows into little hideaways that are barred to most boats. When you find that hidden anchorage, if you wish to sleep aboard you will not be able to lie down on the sole; the thwarts get in the way. Sleeping space can be achieved by using inserts between the thwarts.

The boat is intended for use with sails and oars. I suppose you could attach an outboard motor, but it seems to me that that would spoil a graceful design. I have rowed my Salty Heaven for five miles at a stretch in a dead calm, but it’s hard work. You need only the slightest breeze to put away the oars and carry on under sail.

Paul Boocock

Paul BoocockA pair of Salty Heavens hard-pressed. Time for the first reef.

Glued lapstrake is a popular and proven method of construction. The pages of WoodenBoat contain hundreds of successful boats that have been built by amateurs using the method. Even so, lapstrake construction is a challenge for a novice. A search of WoodenBoat’s archives will turn up how-to articles, with useful advice on such things as spiling the planks and fitting the gains. Another good resource is the Clinker Plywood Boat Building Manual, by Iain Oughtred, available through The WoodenBoat Store. The book takes you through the whole process step by step with clear instructions and plenty of illustrations.

Much has been written about coating wood with epoxy to seal it off from moisture. The designer, who is a trained shipwright, disagrees, maintaining that the epoxy will eventually crack. When water inevitably soaks into the wood, it may then be trapped. When finishing off the Salty Heaven, he recommends using paint and varnish, and keeping the coatings in good condition. On Mikey’s own boat the varnish has been replaced with a mixture of linseed oil and pine tar.

Why a two-masted rig on a 17′ boat? The spread-out rig keeps the center of effort low, so the boat heels less than if it carried a single, tall stick. Some might argue that the mizzen is so small that it doesn’t earn its keep. If she were ketch rigged, the larger mizzen would sit right in the middle of the working part of the boat, where it would be much in the way. The yawl leaves the space clear. The mizzen is especially useful when reefing. Sheeted in hard, it holds the boat’s head into the wind while you drop the mainsail to tie in the reefs. Salty Heavens carry their mizzen stepped off to one side so as not to interfere with the tiller.

To sum up: The Salty Heaven is responsive and fun to sail, without the demands of a modern high-performance sailing dinghy. She’ll take you for an afternoon solo sail, carry a few friends down the bay for a picnic, or accommodate one crew and a load of camping equipment on a week’s camp-cruising. She’s a good, wholesome all-rounder. ![]()

Salty Heaven is a surprising blend of resourcefulness, tradition, and performance. The boat is intended for day sailing and camp cruising, and most of its hardware and fittings are shop-made. Simple lug sails set on unstayed masts

Particulars: LOA 17”, Beam 5’9”, Draft 8”, Sail area 146 sq ft

—-

This boat profile was published in Small Boats 2012 and appeals here as archival material.

Love the the lines of the Salty Heaven

Thanks