Emergencies

The right preparation and equipment should get you through most emergencies. Often, it’s best simply to avoid situations that could turn ugly. In a squall or thunderstorm, for example, go ashore. If you can’t, get your sailing rig down, put out an anchor (or possibly a bucket on a long line as storm anchor), and sit in the bottom of the boat.

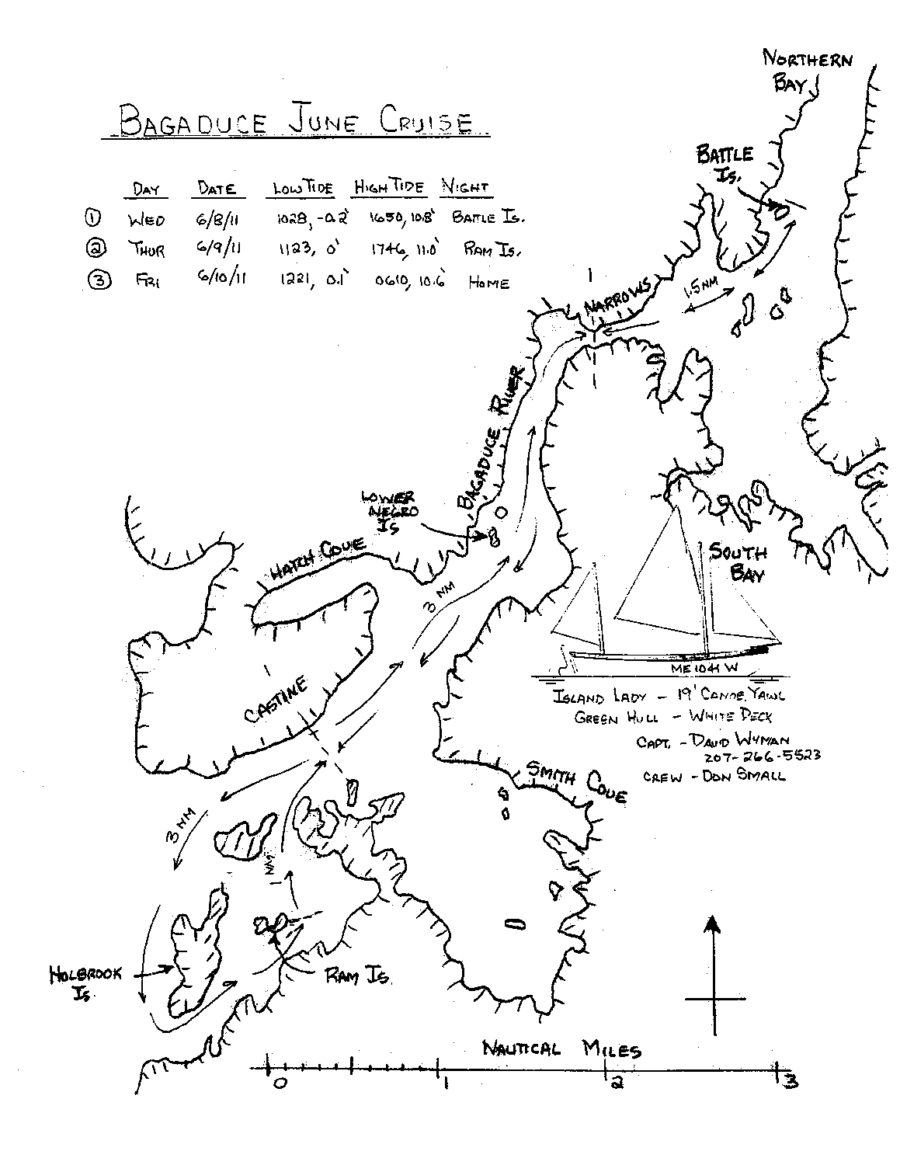

Someone who has gone overboard may need help getting back aboard. This is especially true if that person is you and you are sailing alone. In very small boats with low freeboard, you can usually climb over the gun-wale. But with a larger boat with more freeboard, this becomes increasingly difficult. On my 19′ canoe yawl, I shaped the rudder so that I can use it as a step. A boarding ladder would also work. Whatever method you choose, practice using it in calm waters before you need to do it for real.

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary WymanFood, water, and foul-weather gear are important for comfort and safety.

If someone does go overboard, be prepared to prevent hypothermia (more on this below). Except in hot weather, anyone who has been in the water should get into dry clothes, which should be stored in a dry bag for the purpose. I also carry a lightweight space blanket that can help keep a person warm.

If I had a serious emergency that required assistance—whether a dangerous injury onboard or an unrecoverable capsize, I would first call “Mayday” on Channel 16 of my VHF. If potential help was nearby, I would use a strobe light or orange flag to show my location, and flares or orange smoke. If no adequate response materialized, I would call 911 on my cell phone. When you’re out on the water, however, there is no rapid 911 response. Help may take an hour or two to arrive. Or, you may have to get yourself ashore and wait for an ambulance. So you should always carry a first-aid kit equipped to deal with major medical issues as well as minor ones. Even more important than your kit is your knowledge of first aid. I recommend taking a first-aid course that includes cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). In addition to that, always carry a small first-aid kit with bandages and over-the-counter medications, along with a stretch bandage, which is useful for sprains or tightly wrapping a bleeding wound.

Major medical emergencies can include cessation of breathing, a bleeding wound, or heart attack symptoms. These can be life threatening and need to be handled quickly. Call for help as soon as you can. If someone has stopped breathing, attempt to get breathing started with CPR. Unfortunately, in most circumstances the success rate is not good, but there may be no better choice, and it may buy time until help arrives. If someone is cut and bleeding, stop the bleeding with bandages, keep pressure on the wound, and in extreme cases apply a tourniquet. In the case of a heart attack, you may be able to keep the person alive long enough for help to arrive with a defibrillator. Giving an aspirin can sometimes save a life in the case of a heart attack. In all these cases, you need to get medical help as soon as possible.

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary WymanA compact first-aid kit handles most medical emergencies likely to occur on small boats. It’s a good idea to take a first-aid course, as well.

For minor aches, pains, and injuries the typical small first-aid kit suffices to ease discomfort and prevent infection. Most kits contain a first-aid booklet, which you should consult so that you use the supplies effectively. Again, knowledge of first aid is most important.

Hypothermia

Of all the harms that may come in small boats, hypothermia, or the cooling of the body core, is perhaps the most dangerous. In a small boat, all it takes to get wet is for the wind and waves to pick up. Keeping dry is the key to keeping warm and preventing hypothermia. As it sets in, you gradually lose mental and physical capabilities. It can be fatal. (Study the many online resources that provide opportunities to learn more about hypothermia, for example, the “Cold Water Survival” section of www.uscgboating.org/fedreqs/default/html.) The body core cools fastest by getting wet, even from sweating or from spray, but most especially from immersion in water.

If you do go into the water, keep as much of your body out of the water as possible, get out as fast as you can, and change into dry clothing right away. Keep warm clothing in a dry bag lashed aboard, so that in the event of a capsize you can change into warm clothing after righting the boat and stabilizing the situation.

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary WymanTo prevent hypothermia, carry extra clothes in a dry bag so they stay dry in case of a capsize. The pants and pullover shown are synthetics, which dry quickly and still insulate even if wet.

Guard against spray and rain by bringing foul-weather gear and extra dry clothes for each person. Provided the weather is reasonably settled and warm, I carry a lightweight long parka that easily fits in my bag. In cooler weather, I carry a full set of foulweather gear or a Type III flotation vest jacket, which in addition to providing flotation also provides some hypothermia protection both in and out of the water. I also carry my flotation jacket in cool weather just in case I need to provide hypothermia protection for someone I’ve pulled out of the water. For camp-cruising, I take gear suitable for any turn of weather.

Wear clothes that wick water away from the skin. Polar fleece synthetics are good, and many consider wool the best. Always avoid cotton, which wicks moisture very effectively and provides almost no thermal protection when wet; many consider it a killer. Wear clothing in layers so you can adapt to the conditions. Even on a warm day, being wet in a breeze can be chilling.

If you get stuck out unexpectedly overnight, you can be reasonably comfortable sleeping in your extra dry clothes and foul-weather gear, and you can wrap yourself in a sail. In a small boat, being adequately equipped and keeping aware of your options is not only the key to a safe and fun trip, but it may also be the key to survival.

Flotation

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary WymanAfter deliberately capsizing his Chesapeake Light Craft Skerry skiff, which has built-in flotation, owner Bill Corbett uses a bucket to bail. When a boat swamps, a lot of water has to be moved quickly.

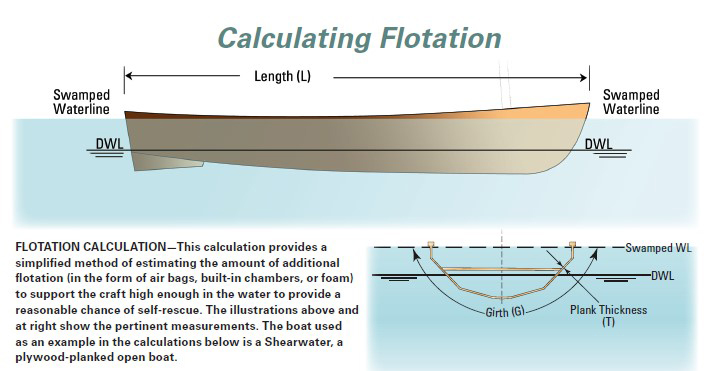

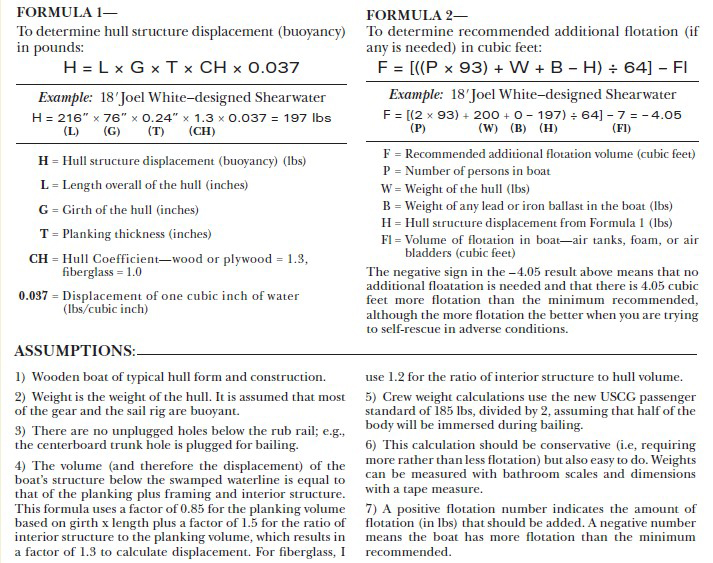

A boat should have enough flotation to not only stay afloat in a capsize but allow self-rescue. Over years of studying traditional boats, I have developed a simplified formula (see sidebar) to estimate additional buoyancy needed to keep the gunwale a few inches above the flooded waterline, and therefore possible to bail. In general, in traditionally constructed boats—without ballast—the cedar planking and other solid woods usually provide adequate flotation. But plywood’s flotation properties are much less, so many of today’s lightweight plywood boats need built-in or added flotation. Many professionally designed or kit boats have watertight chambers for flotation, but sometimes home-built boats do not.

Alternatives to built-in chambers include inflatable buoyancy bags and foam blocks, well secured inside the boat. The instability of a swamped boat can be improved by placing flotation outboard along the sides and by providing enough so that part of the flotation stays above the swamped waterline.

All of the above assumes that the boat has no ballast. If there is ballast, include its weight in the calculations. If you need to carry ballast, I recommend using water ballast, which is neutrally buoyant in a capsize.

With a new boat, it’s always a good idea to take a sunny day on a warm pond to practice swamping, self-righting, and bailing. Playing at self-rescue may well save your life in a more serious situation.

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary Wyman Like many modern boats, the CLC Skerry’s built-in air chambers forward and aft keep the boat high enough in the water so that one person aboard can bail with a bucket.

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary WymanA Joel White–designed stretched Shearwater has no built-in flotation, so instead inflatable bags are secured under the foredeck, shown here, and also under the thwarts.

Conclusion

As you head out in your small boat, remember to take your sea sense and a good dose of common sense along with your gear. Be willing to stay put in a quiet anchorage if the weather turns nasty. In the end, the most important things for a safe voyage—once your boat is adequately equipped—are to listen to the wind, watch the weather, and enjoy the day.

Very easy to make a webbing or rope sling to help reboard. It can be fastened to your boat where you can reach it from in the water. Grab it, drop it into the water. Step in and reboard. You need to experiment to find the right length. And slip a bit of garden hose onto the sling so it can keep it open under your foot.

I just did 40 hours on a dinghy sailing course. I am heavy and could not get back on board. Not even with a rope ladder which is a lot harder to climb than people think. I will need a solid ladder. Telescopic or fold away.

For flotation, your goal in a sailing boat is enough to keep the centerboard or daggerboard trunk top above water with the boat fully swamped. If you can’t do it, do as we used to do in log canoes, keep some rags, t-shirts, etc. handy to stuff into the top of the trunk.

And tie a line to your bailing bucket so you can retrieve it when you toss it overboard. Same with plastic store bought or cut-down gallon-jug bailers. I’m picky about these and when I need a bailer I look for a product in a heavy plastic jug. My hand bailer preference is my wooden leather one. Bailing fast will keep you warm.

I’ve also built a transportable battery-powered electric bailer using a welding-rod case which is helpful.