Rosemary Wyman

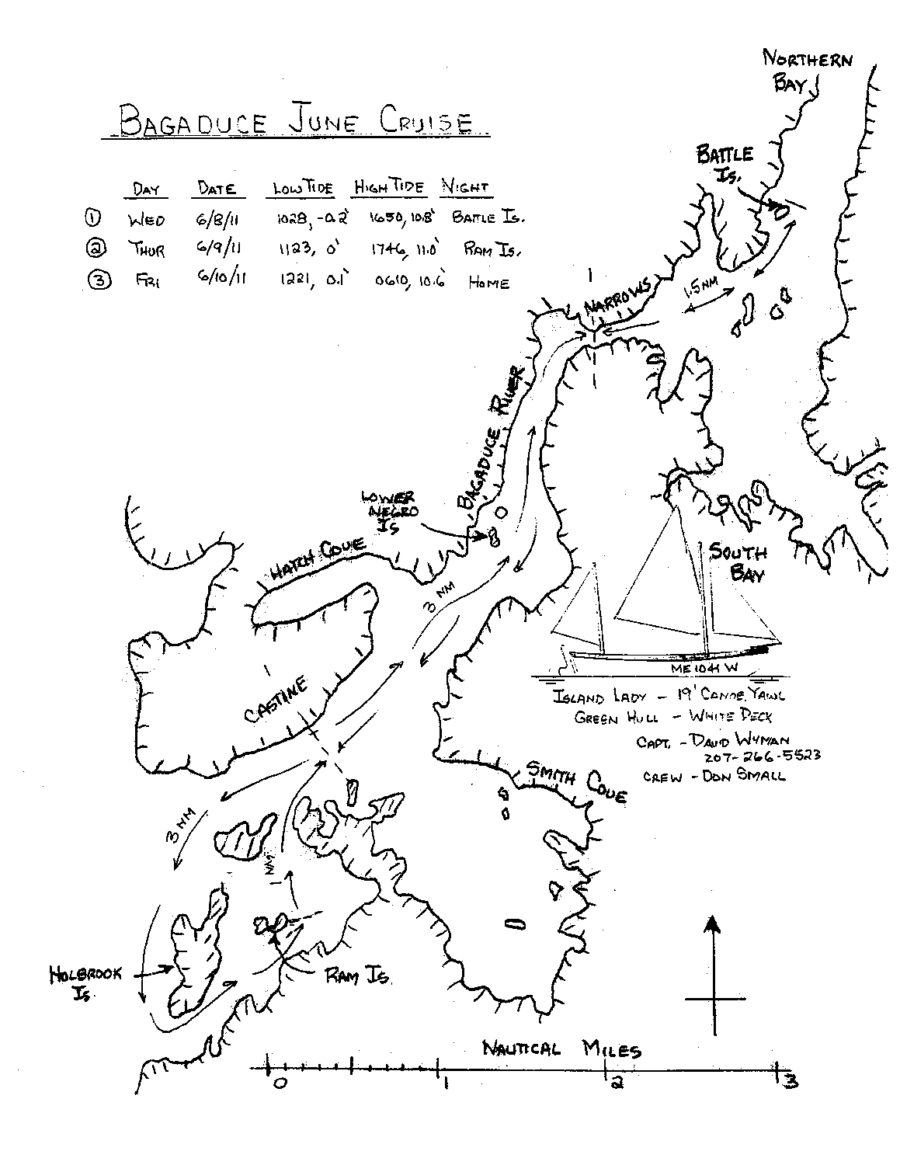

Rosemary WymanOriginally used as a beach-launched fishing boat, the No Mans Land Boat, named after an island near Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, is a seaworthy double-ender. Several have been documented, and this one, built by the author, is based on a Beetle builder’s half-model from the 1880s.

As s working-sail fleets faded after the turn of the 20th century, astute observers in numerous corners of the world recorded their last remnants. The old way of building—carving a half model and then measuring it—was still very common, so without photography and field documentation, many boat types simply would have been lost. The No Mans Land Boat was certainly one of these.

In the 1930s, these double-ended cod-fishing boats caught the attention of historians Howard I. Chapelle, M.V. Brewington, and others. The Smithsonian Institution, where Chapelle became a curator, has a rigged model built by a No Mans Land veteran. In the 1950s, another historian, Robert Baker, found an 1880s boat and restored it for his own use; that boat and another now reside at Mystic Seaport Museum, and Baker documented both. So plans for the type exist, and they are as enticing today as ever.

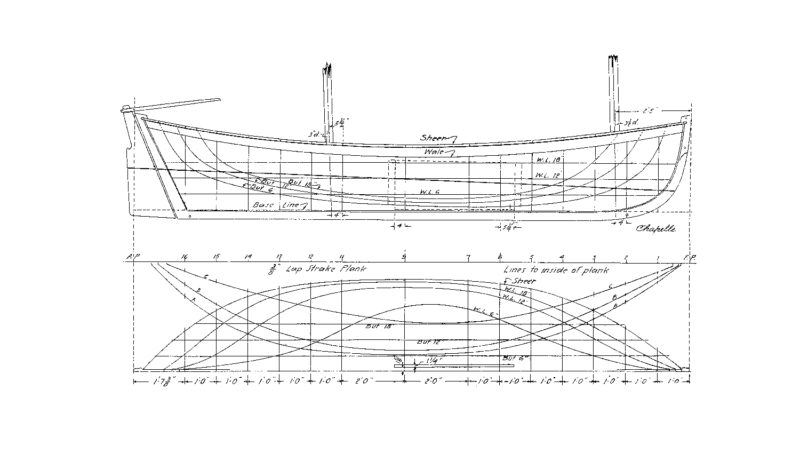

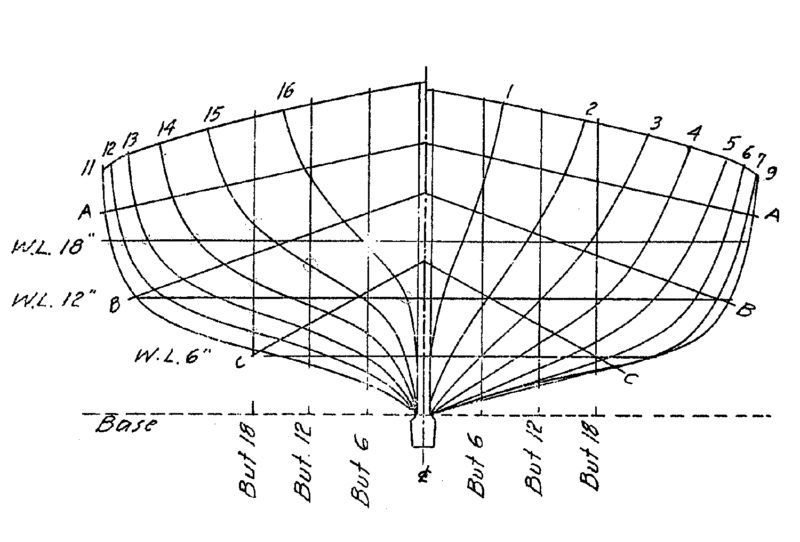

The hulls are extraordinary. In the best of them, the sheerline has a lovely upward sweep forward and aft, and the section lines aft have shapely reverse curves culminating in a steeply raked sternpost. They are commodious, inviting the imagination to wander.

Martha’s Vineyard cod fishermen used them at nearby No Mans Land Island and praised their seaworthiness. They were drawn ashore at day’s end, and their sharp sterns facilitated relaunching stern-first into the surf. At season’s end, most were left ashore when the families moved home. They were well-built by capable craftsmen, including Joshua Delano of Fairhaven, who is said to have built 50 or 60 of them, and by the Beetle family of New Bedford, renowned whaleboat builders.

Jonathan Taggart

Jonathan TaggartHaving the foresail tack made off to the stemhead is efficient and powerful, but best reserved for long tacks.

They had straight keels with a lot of drag. Centerboards were offset, running through the garboard and alongside the keel. This preserved the integrity of the vertical keel and made beach stones less prone to jamming the slot. They were two-masted—using the parlance “foresail” and “mainsail,” as in schooner practice, not “mainsail” and “mizzen,” as in ketches, despite the diminished size of the after sail—and they were sprit-rigged, though some carried gaff foresails. In the March 1932 Yachting, William H. Taylor has a quotation—maddeningly unattributed—calling the type “almighty able, and they’d claw out to windward through anything that blew.”

With good looks and a solid reputation among seasoned mariners, these boats naturally have caught the attention of modern boatbuilders. But this is not the boatbuilding project for a beginner. Experience is essential and a good deal of determination highly advisable.

To begin, all the plans present problems. Two of the finest-looking hulls have no construction plans at all. One, a hulk by an unknown builder, was documented by Frederick H. Huntington and published in the April 1932 Yachting. The other was drawn from an 1880s Beetle half model documented by Chapelle, published in American Small Sailing Craft (W.W. Norton, 1951). The Huntington boat, which Roger Taylor wrote about in Good Boats (International Marine, 1977), has a sail plan that invites change (more on that below), and the Beetle has no sail plan.

Rosemary Wyman

Rosemary WymanFAR & AWAY is rigged with a dipping-lug foresail, ordinarily with its tack made off to the stemhead. But with its tack made off to a belaying pin at the mast gate, it can sail as a standing-lug, simplifying tacking in tight quarters.

The Huntington boat is handsome, no doubt. But far and away my preference—for the boat eventually launched as FAR & AWAY—is the Beetle. Chapelle captioned the drawing with this: “No Mans Land boat of the more powerful type designed to sail well.” He had me right there.

Construction takes a lot of thought and a lot of decision-making. A builder who is adept at the drawing board could develop a full construction plan. I did not: I started building, making decisions only as I needed to. If you are lost without a construction plan, it would be best to develop one or get a boat designer involved. Otherwise, look to Mystic Seaport’s plans catalog. The two boats in the collections there were both fully documented by Baker; although I don’t think either has as fine a shape as the Huntington or the Beetle, one of them, ORCA, a Delano construction from 1882, has great potential. However, she was batten-seam planked, which is uncommon these days. And, as always, workboat interiors might not suit modern purposes.

In construction, be faithful to the hull form. The challenge will come primarily in steaming and bending the planking aft, where the lovely and enticing reverse curves can be alarming while shaping and hanging lap-strake planks. Careful lining off and patient work pays.

Having the centerboard offset to one side not only prevents jamming—as valid today as it was a century ago—but also makes the boat trailer well. The long, straight keel settles nicely into rollers. A tongue extension may be needed for launching, though, depending on the ramp’s slope. The straight sternpost makes shipping the rudder easy.

Robin Jettinghoff

Robin JettinghoffA straight, raked sternpost makes shipping the rudder easy. The author cast all his own bronze fittings, including pintles and gudgeons.

The large, open cockpit is commodious—on my boat, which is a little less than 18′, I’ve had six aboard quite easily, and four in comfort routinely.

The Beetle boat has a one-sheet plan showing lines, details of the centerboard (which I altered in everything but length and placement), stem profile, rudder profile, maststep locations, mast diameters (which I increased), and mast rake (which I did not change). This plan leaves a great deal to the imagination. I used a Scandinavian-inspired style of sawn-frame construction, and because each frame has rolling bevels and is joggled, or given something like a lightning-bolt shape to fit to the inside of the lapstrake planking, the process is a bit like fitting 50 or 60 breasthooks. I built that way because I wanted the challenge of doing it—and, rest assured, it was a challenge. I also wanted a stout boat. I used a deck and coaming layout, plus a mast gate style, derived from Bristol Bay sailing gill-netters. I set my seat riser height by getting in the boat and seeing what was comfortable, with a mocked-up coaming and long oar. I put in side seats but stopped them short of the forward thwart so that rowing two-abreast would be easier. My floorboards are athwartships, a style I noted in Sweden. My sails adopted some French practices.

Like most workboats, No Mans Land Boats were designed to carry a load. They also carried inside ballast, some of which could be discarded as the catch came aboard. Published sources mention sandbag ballast, stone ballast, or “a couple of hundred pounds of ‘handle iron’ pigs,” in the case of the March 1932 Yachting article. Today’s drive toward ever-lighter plywood construction and very light scantlings supported by tenacious glues might not work well here. My boat is built heavily, but I nevertheless added 150 lbs of internal ballast to get her down on her lines, and she might take a little more. She’s a bear to row—not unlike, say, a large Norwegian faering. I often row alone, and in a flat calm I’ve hit 3 knots. But instead of rowing solo into the teeth of a blow, I’ve set the hook and waited more than once. She’s primarily a sailer. Built exceptionally light, she’d need quite a load of ballast, which could make her quite stiff and a very different kind of performer. In my view, extremely light construction is overrated for a sea boat.

The existing sail plans, too, need revision. The original rigs made it easy to work amidships while hauling a catch. More sail—with easy reefing—makes more sense today. Maynard Bray, WoodenBoat magazine’s technical editor, owns MIRTH, a boat built to the Huntington design in the early 1970s, and he feels that her foresail should be larger. His advice helped when I was developing the sail plans for FAR & AWAY (see WB No. 202). I chose a dipping-lug foresail that would probably never be his cup of tea, but such variation is what taking on a challenge like this is all about. Experiment. Play. Try something, and if you don’t like the way it works, try something else.

The authentic sail plan also has a mainsail “club,” a baseball-bat-sized boom laced to the after third of the foot of the sail—which most of us today wouldn’t want flailing about overhead. Note also that a gaff rig like MIRTH’s requires at least a headstay and perhaps one shroud per side. To my thinking, that negates the advantages of an unstayed rig, which is easy to strike when necessary, for example when she’s on a mooring and a gale is forecast. In use, I find I make my foresail a kind of hybrid: when short-tacking, I take its tack aft to the mast gate to make it a standing lug sail. On long boards, I gain a half a knot or more by dipping the sail and setting the tack to the stemhead. My mainsail is boomed and so is MIRTH’s; it’s the best way to gain an effective sheet lead on a double-ender. A rope traveler gets the sheet over the tiller.

Benjamin Mendlowitz

Benjamin MendlowitzMIRTH, owned by WoodenBoat technical editor Maynard Bray, was built by Arno Day and Joel White to the Frederick Huntington plans published in Yachting magazine in the 1930s. Her gaff rig requires a forestay and one shroud per side.

FAR & AWAY surprises me, and others, above all by her speed under sail. Sailing to weather in company with a friend’s modified Herreshoff H28, I better than matched him tack-for-tack. In the Small Reach Regatta and elsewhere, this heavy old fish boat holds her own and then some against other displacement hulls. I think that has everything to do with her hull shape and her ability to carry a large rig.

In tacking, I free the foresail sheet, put the helm down, and haul the mainsail simultaneously. As she comes through the eye, I free the mainsail and sheet in the foresail. This works in all but the heaviest weather—in gusts up to 30 knots, I’ve had trouble tacking, partly because I was towing a dory and partly because I had struck the main to reduce sail and couldn’t use it for balance. I might try a small triangular storm foresail or build in a balance reef—a diagonal reefpoint from the upper reef line on the leech to the heel of the yard. But that’s just another of a long line of pleasant puzzles presented by a boat that is teaching me a new way of looking at everything I thought I knew.![]()

Beetle boat plans are available from Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Ships Plans. Frederick Huntington’s plans were published in the April 1932 Yachting and in Roger Taylor’s Good Boats (International Marine, 1977).

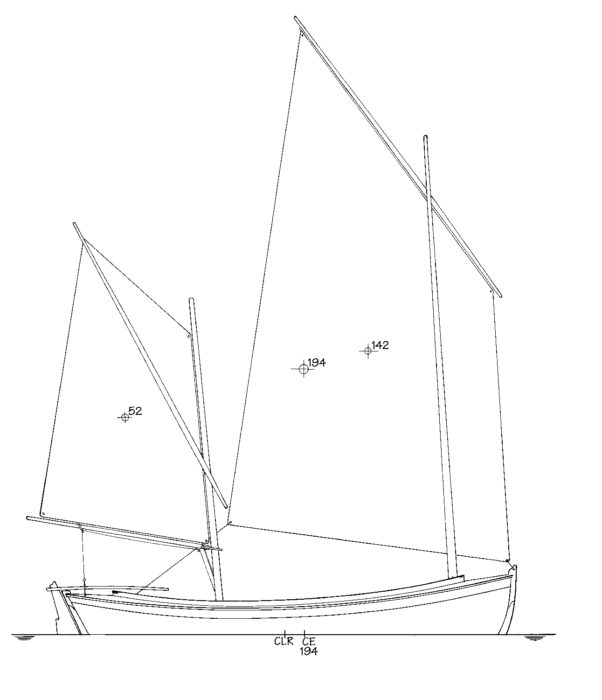

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonThe one-sheet plan for the Beetle No Mans Land Boat, published as Plate 63 in Chapelle’s American Small Sailing Craft, has lines, offsets, and details (not shown) of the rudder and centerboard. Without construction plans or a sail plan, building the boat calls for judgment and experience. The sail plan shown is the final choice of several developed by the author.

Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian InstitutionNo Mans Land Boat Particulars: LOA 17′ 8″, LWL 16′ 5 ½”, Beam 6′, Draft (board up) 1′ 6 ½”, Sail area 194 sq ft (as shown)

Greetings, Tom, It has been a long time since we talked. This is a beautiful boat. I visited Phil M. in Nahcotta.

Jeff Heater

Waldron WA

Nice to hear from you, Jeff—lot of water under the bridge since we left San Juan Island. Hope you’re well, and give my best to Vicki!

I own a very similar boat. It’s a Crotch Island Pinky built by Peter Van Dine in 1977 in fiberglass. It has a spritsail rig but has the same rugged character.