This is a gentleman’s Whitehall.” That’s how Steve Holt describes the Shaw & Tenney Whitehall, a 17′ 9″ recreational rowboat based on a legendary 19th-century working type. Holt is proprietor of Shaw & Tenney, the 150-year-old, Orono, Maine–based maker of wooden oars and paddles. The company itself is something of a commercial legend for its longstanding success in its small niche, and this Whitehall, a modern wooden version, is Shaw & Tenney’s first boat offering in all of those years.

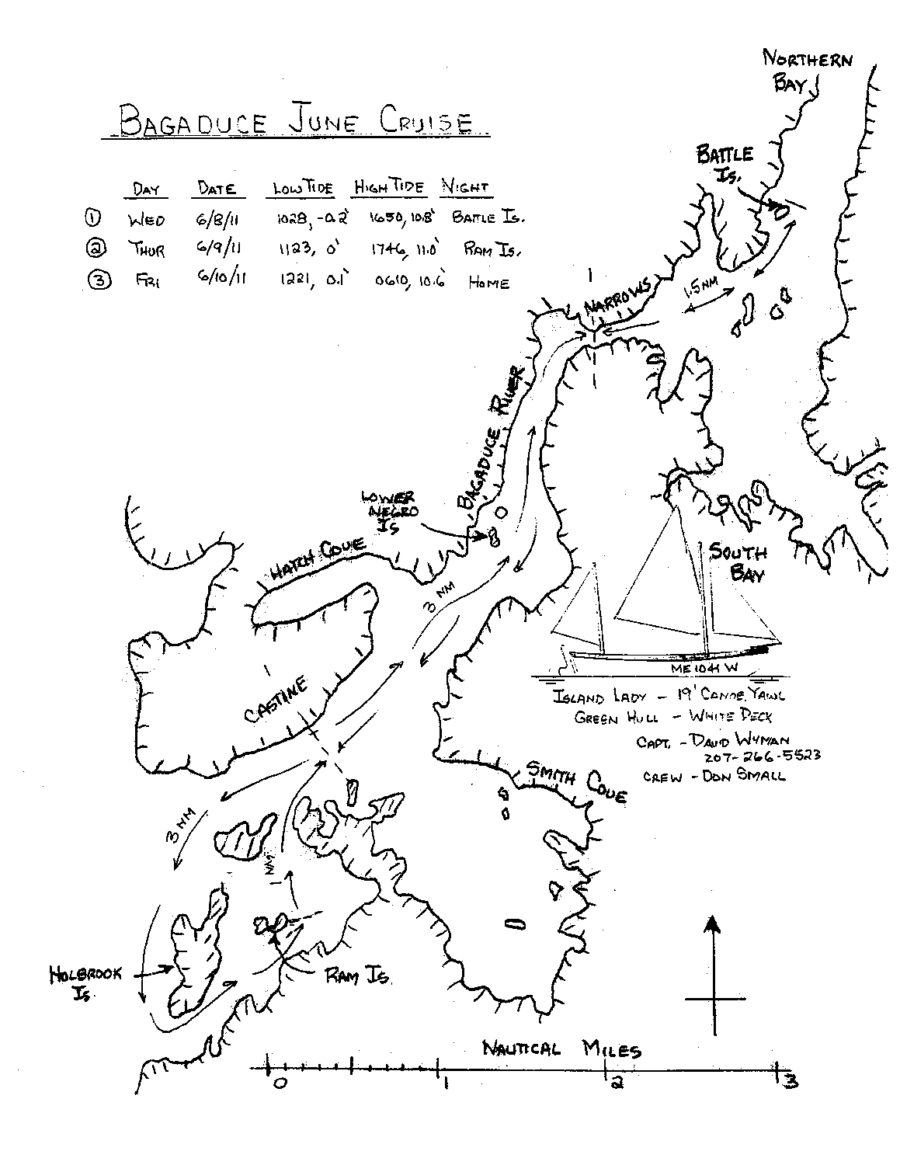

The Whitehall pulling boat is widely believed to have originated in New York and been named for Whitehall Street in that city, though the great small-craft historian John Gardner cast some doubt on that supposition in his book, Building Classic Small Craft, Volume 1. He said the boat’s origins were “vague and shadowy,” and suggested that it might even have been imported from England. Regardless of the type’s roots, it was in active service in New York by the 1820s, and it spread to Boston, where it developed distinctive regional traits.

“The Whitehall was not a ship’s boat, but a vehicle of harbor and coastwise transportation,” writes Gardner. “Not only were these boats the choice of crimps and boarding-house runners, but of nearly everyone else as well who required reliable and expeditious transportation about the waterfront or from one part of the harbor to another—ship chandlers, brokers, newspaper reporters, insurance agents, doctors, pilots, ships officers, port officials, and many others.

“Gentlemen of that day,” continues Gardner, “seeking a pleasure boat, frequently adopted modifications of the Whitehall workboat.” The impulse to adopt these boats for recreation has not diminished after nearly 200 years. With its purposeful plumb stem and seductive wineglass transom—and good rowing characteristics—the Whitehall still often makes the short list of boats for a recreational rower with a penchant for classical good looks. But refinements are, indeed, in order to bring this type into the realm of pleasure rowing, for a commercial Whitehall, while easy on the eyes and oars, could be relatively heavy and hard to turn. Which brings us back to the Shaw & Tenney Whitehall.

N. Forster-Holt / Shaw&Tenney

N. Forster-Holt / Shaw&TenneyThe new Whitehall’s construction is strong and does not require frames. Some rowers, however, will take comfort in their presence, and so Shaw & Tenney offers the option. The boat we see here is framed in sassafras.

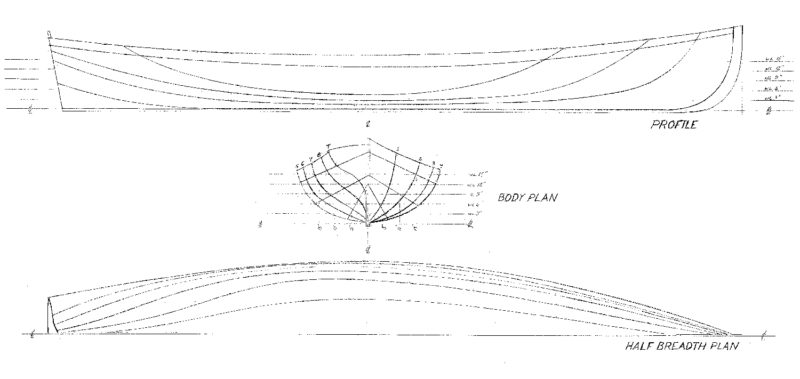

Shaw & Tenney developed its Whitehall because “we have a market that appreciates fine rowing,” said Steve Holt. But the boat is not simply a business venture for Holt; it’s also the fulfillment of a “desire to build something that hadn’t been built before.” That “something” that hadn’t been built before is a glued-lapstrake-plywood Whitehall pulling boat, with proportions refined for recreational rowing.

“Glued lapstrake plywood” means that the boat’s planks are cut from sheet plywood, bent around a building jig as they would be in traditional construction, but glued together with epoxy rather than being fastened with rivets or nails. This popular construction technique yields a hull of traditional lapstrake appearance, but without the traditional worries of leaking and drying out. The boat can therefore live on a trailer between outings, with no need to soak up in order to be watertight. A glued-lapstrake hull should simply not leak, ever. If it does, then something is wrong.

Benjamin Mendlowitz

Benjamin MendlowitzThe Whitehall’s forward rowing station is used when two rowers are pulling, or when a passenger is seated in the stern sheets.

The Shaw & Tenney Whitehall is planked in 6mm sapele marine plywood. While a glued-lapstrake hull does not require frames, this boat has them. A frameless hull is a bonus in regard to cleanliness and refinishing, for it allows unfettered scrubbing or sanding of the inner planking, and there are no frames to trap dirt. But the absence of frames also reveals the boat’s modern glued construction; and a belly full of frames just makes a boat appear so classical, so sculptural. The Shaw & Tenney Whitehall has bright-finished sassafras frames contrasting with its painted inner planking. Although widely spaced, they certainly add some strength to the hull. They also provide some visual relief to that expanse of white inner planking. And, finally, they provide blocking for the inwales, creating an open gunwale structure that allows water to drain out entirely when the boat is inverted. Of course, this open gunwale arrangement could be accomplished with simple blocking, too. The optional vestigial frames, in short, are a personal preference—though not a necessity.

The boat’s transom and bright-finished accents are of sipo mahogany, prized for its so-called “ribbon-stripe” grain. The keel is of white oak—heavy, but heavy in the right place.

The development of this boat began as a conversation with Ben Fuller, curator of the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine. Fuller is also a former curator at Mystic Seaport Museum, where that conversation took place at the 2008 WoodenBoat Show. The mandate was for a tandem, fixed-seat classical rowboat that could also be rowed by a single person—and could be adapted for a sliding seat, if one were desired. “We looked at hundreds of different designs,” said Holt.

N. Forster-Holt / Shaw&Tenney

N. Forster-Holt / Shaw&TenneyThe Shaw & Tenney Whitehall comes equipped with outrigger oarlocks at the primary rowing station. These oarlocks flip out for use, and are folded inboard for stowage. They allow for oars 1′ longer than would standard, gunwale-mounted hardware, and are also available separately from Shaw & Tenney.

The resulting boat is an original design, but it most closely resembles a recreational model, the Bailey Whitehall, on display at Mystic Seaport—“a fancy pleasure Whitehall,” as described by John Gardner in Building Classic Small Craft. The Bailey boat measures 16′ 9″, and carries a beam of 3′ 7″. The boat’s scantlings are minimal, to save weight, and the lines are “drawn extra lean and fine,” according to Gardner.

The Shaw & Tenney boat is also extra lean and fine. It resembles the Bailey Whitehall, but the newer boat is 17′ 9″ long and 3′ 7½” on the beam—proportionally narrower than even the fine-lined Bailey boat. “Our boat,” says Holt, “is not meant to carry four men and 600 lbs of supplies out to a ship.” But at the launching festivities at Pushaw Lake near Orono, the boat did carry 600 lbs of people through a 2½’ chop. “No trouble at all,” Holt reported of that outing.

I too had no trouble at all when I tested the boat in a 1 2–15-knot northerly at Pushaw Lake on a sparkling afternoon last August. I’d had a brief spin in the boat a few weeks before, when we were shooting this magazine’s cover, so I knew that it tracked very well in a straight line, and that it turned slowly. So I was impressed in August, when leaving the dock in tight quarters and a breeze, that I could practically pivot the boat in its own length with short bursts of opposing oar strokes. Once aimed where I wanted to go, the boat tracked dead straight, despite the breeze being on the forward quarter.

Benjamin Mendlowitz

Benjamin MendlowitzBecause of its long, straight keel, the Shaw & Tenney Whitehall is not nimble in sharp turns, but it’s fast and it tracks straight for long distances.

Steve told me as I left the dock that the boat responds well to a modest pace at the oars—that a fast clip would wear me out sooner, but not necessarily make the boat go faster. This turned out to be true, and it was an especially useful observation when I was rowing the boat upwind. I’d take a firm stroke, and then wait and watch the shore. One one thousand…two one thousand…three one thousand…four one thousand…. The boat continued to carry its way forward, despite the headwind. Then I’d take another stroke.

The night before my Pushaw Lake test, I’d been rowing a popular small dinghy at the WoodenBoat waterfront, in a similar breeze. This smaller boat is famous for its good rowing qualities, but I was struck that evening by how the headwind stopped it in its tracks between strokes. A staccato rhythm was required to maintain headway. I don’t mean this observation as a criticism of that dinghy, for I certainly would not want a tender of the size and weight of the Whitehall. But the role of a little weight and waterline length in keeping a boat gently moving forward in difficult conditions was illuminating.

After rowing a suitable distance upwind, I rested for a moment to recover and make a few notes. Driven by the wind, the boat headed for the barn. It was a great ride back, with my strokes as much for steering as for drive. I tried the boat on different points of “sail.” Dead downwind, broad reach, beam reach…she tracked straight no matter what the relative wind. I rested one oar and pulled with the other, watching the shore astern as I did. The boat’s stern would steer slowly across the backdrop of trees. As the breeze came on to the stern quarter, I’d need to drag the lazy oar briefly to get through the broad reach—a particularly stable wind angle, it seems.

As noted above, I had a brief outing in the boat in calm conditions, and she’s a joy to row in a flat sea and no wind. While not a nimble boat, it’s fast. And it’s beautiful. I can imagine having one for morning rows on the Penobscot River, and I’d feel confident making the two-mile crossing of that river’s lower portions—even in its frequent short, steep chop.

Steve’s 11-year-old son Sam asked me what I thought of the boat when I returned from my breezy trip on Pushaw Lake. I told him some of the things that I’ve just told you—that the boat carries beautifully between strokes, but that it didn’t take excessive power to get it going in the first place, and that it tracked so well. Sam thought for a moment, and then replied with what I think is a more succinct description of the boat’s handling qualities than I’ve been able to muster: “It doesn’t smash up and down because it’s too light, but it isn’t too heavy, either.” ![]()

To order a Shaw & Tenney Whitehall, or for information, contact Shaw & Tenney.

Modeled on a recreational Whitehall conserved at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, the Shaw & Tenney model is narrower than its working forebears. Particulars: LOA 17′ 9″, Beam 3′ 8″, Weight 145 lbs

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.