" Is that a PocketShip?” Even though it was the first time I had ever launched my PocketShip, it was not the first time a stranger had approached me to ask about it. This stranger turned out to be very familiar with the design, having followed it since Chesapeake Light Craft introduced it. What would prove to be the usual suite of questions followed: Did I build it myself? Plans or kit? How long did it take? How does it sail? He expressed his enthusiasm for the PocketShip and his dream to build one.

Jon Lee

Jon LeeThe PocketShip was designed to be towed by a modest car with a four-cylinder engine. The full-sized sedan here is more than up to the task.

John Harris, the proprietor of and chief designer for Chesapeake Light Craft, designed the PocketShip as his personal boat. “I’d owned a production fiberglass pocket cruiser, which sailed well but was hellish uncomfortable,” he explained. “I had a hunch that I could design a sailboat with a 15′ length-on-deck that not only sailed extremely well, but was ergonomic for someone of my 6′ 1″ height.” The boat had to be light enough to tow to Florida behind his four-cylinder car, fast and seaworthy enough to sail overnight to the Bahamas, and commodious enough for a week’s cruising once there. He drew a centerboard gaff sloop with a doughty profile. The waterline length is 13′ 8″, and the boat weighs around 1,200 lbs when rigged, ballasted, and loaded with provisions. John packed a lot of boat into a small, well-balanced package.

Jon Lee

Jon LeeThe boom gallows catches the boom and gaff when the main is lowered.

The PocketShip struck a chord with amateur boatbuilders, and a flurry of interest from potential customers led John to add the design to the CLC offerings. The promise of big-boat cruising adventure in a petite, built-it-yourself, trailerable package proved irresistible to many, and at last update more than 300 kits and plans have shipped to locations around the world.

The PocketShip is a do-it-yourself project with a scope and complexity that a handy amateur can readily contemplate. It is available as a kit with CNC-cut plywood parts, epoxy, epoxy thickeners, fiberglass, drawings, and manual. Hardware, timber, and sails are available as optional packages. I built from CLC’s plans, huge rolls of paper with full-sized patterns for nearly all parts. The 280-page manual is a masterpiece, with minutely detailed instructions, readable prose, and clear photographs and illustrations. While PocketShip is best for the intermediate-level amateur, the quality of the manual has enabled complete novices to build fine PocketShips.

I built my PocketShip in a one-car garage over the course of two years. When I decided to order plans instead of a kit, I felt that I had to cut out all the wood myself in order to claim I had built my own boat. If I were to do it over again, I would build from a kit; it would get the build started faster, produce more precise work, and still require enough labor to provide a legitimate claim to a self-built boat.

Jon Lee

Jon LeeThe 2.5 hp four-stroke outboard is the maximum recommended auxiliary power. A larger outboard would add an unnecessary burden to the transom.

The PocketShip is constructed using the stitch-and-glue plywood method. Having built two kayaks before the PocketShip, the basic techniques were familiar to me, and the hull went together much like a giant, complex kayak. I picked up some new skills such as scarfing plywood (the kit uses CNC-cut puzzle joints), melting lead for the keel, and rigging the sheets, halyards, and stays. The manual always kept things from getting intimidating; it breaks down the building into a series of small, achievable tasks, most of which can be completed in weeknight sessions. Some things, such as the big fiberglass jobs, are best reserved for weekends.

courtesy of Chesapeake Light Craft

courtesy of Chesapeake Light CraftFor the performance-minded sailor, the optional spinnaker adds power for sailing off the wind.

Construction begins with the keel assembly, which includes the centerboard trunk and has two compartments, one at each end of the trunk, that are filled with 108 lbs of lead, melted and poured in. (Another 150 to 200 lbs of ballast—bags of lead-shot—will later get set in the bilges of the completed boat.) The finished keel assembly is dropped into a building cradle made of two female molds. The hull bottom and sides are then dropped in and wired together with temporary 18-gauge-steel wire stitches. Next, an array of plywood bulkheads and floors are stitched in place. The joints are then permanently bonded with big epoxy fillets and the entire interior is sheathed in fiberglass. The decks and topsides are also stitched, glued, and ’glassed. There are a few fiddly bits of carpentry along the way, where timber needs to be cut at a complex angle, but these tasks tend to be welcome breaks from the epoxy work.

The mast is a tapered hollow box, built up from four 16′ spruce staves. The bowsprit, boom, and gaff are all solid timber with rectangular sections, milled down to attractive tapers. While traditional in appearance, the rig is fairly modern in the details, including a roller-furling jib and sail track for the main. Rigging requires a wide variety of blocks, cleats, and eyestraps, and careful routing of the running rigging.

Getting the PocketShip to the launch site and out sailing is a breeze. For easy trailering, the mast is stepped in a tabernacle and folds down onto the boom gallows. On reaching the launching ramp, you start by casting off the tie down that secures the mast to the boom gallows. The bobstay also must be shackled to the bow eye, unless the geometry of your trailer permits it to remain attached. Standing in the cockpit, you thrust the mast upward toward vertical and haul in on the jib halyard, which does double duty as a forestay, pivoting the mast into place. Once the boat is in the water, drop the centerboard and slide the mainsail onto its track. When this process is well-rehearsed, it is possible to be underway within 10 minutes of arriving at the ramp.

The boat is designed with singlehanding in mind, with all lines, including the jib’s roller-furler line, led to the cockpit. For a relatively heavy displacement boat with a 13′ 8″ waterline and 6′ 3″ beam, the PocketShip has surprisingly inspired sailing qualities. John Harris likes his PocketShip to sail fast, and worked hard to get as much speed as he could out of this little vessel. The hull lines are fairly refined and carry a good dose of racing dinghy in them. The boat has a single hard chine, a V bottom, and a surprisingly fine entrance. If it were not for the 268-lbs of ballast required to keep her on her feet, it could probably be induced to plane quite readily. The ample sail area adds to performance; with a 109-sq-ft main and a 39-sq-ft jib, the boat has no shortage of power.

courtesy of Chesapeake Light Craft

courtesy of Chesapeake Light CraftThe prudent reefing and PocketShip’s ballast, over 250 lbs divided between the keel and bilge, lets the skipper sail while safely seated in the cockpit.

For a gaff-rigged boat, the PocketShip is close-winded, able to sail to within right around 50 degrees of the wind. A beam reach is where it really shines. The boat almost effortlessly plunges forth at a sprightly 5-ish knots and settles into a groove that yields delightful sailing. At speed, the PocketShip will plow jauntily through chop, and is stable and confident in rough conditions. Full sail can be carried up until the wind hits 10 to 12 knots; above that, a single reef will calm the boat down substantially without sacrificing any speed.

With its large sail area, a PocketShip will propel itself in even the lightest of airs. If currents are a fact of life in your home waters, however, a 2- to 2.5-hp outboard motor, hung on a mount fixed to the transom, is essential. The boat is easily driven and zips along under power. The manual notes that a pair of oars and a yuloh are auxiliary power options, good for a couple of knots, and though accommodations for them are not included, they would be easy enough for the builder to add.

Jon Lee

Jon LeeThe cockpit foot well is kept to a minimal but functional size to make more room in the cabin for storage and sleeping.

The cockpit is roomy enough to accommodate three or four adults. It is an expansive and comfortable space, almost as well suited to lounging about as a living-room couch. The narrow, shallow footwell is a compromise with the sleeping accommodations below it, but the PocketShip’s cockpit is perfectly functional.

Jon Lee

Jon LeeThe cabin provides sleeping quarters with the extensions, to left, under the cockpit seats.

The cabin has an open layout; you sit or sleep directly on the floorboards, with legs extended aft under the cockpit. At the forward end of the cabin there is a large storage area, and additional space aft, below the cockpit decks. There are comfortable sleeping accommodations for two full-grown adults. Though the cabin is small, it is possible to spend time below without discomfort, as I discovered during one very rainy weekend.

Jon Lee

Jon LeeThe PocketShip performs well in light air, and when the winds fail, it is light enough to be propelled by sculling or rowing if the builder choses to rig the boat for oars.

There is a degree of celebrity that comes with sailing a PocketShip. A PocketShip owner gets used to being photographed out on the water, complimented at the dock, and peppered with questions at boat ramps. On a recent trip to Friday Harbor in Washington’s San Juan Islands, my PocketShip looked Lilliputian moored next to the long rows of enormous, glittering, white production cruisers. Yet, the tourists walking the docks were inevitably drawn to my little red boat. I had to abandon my plan to lie about and read, and instead respond to the stream of questions and compliments that the boat drew. While the monster yachts that surrounded me had galleys, settees, even televisions, one little boy stood wide-eyed, marveling that such a little boat could have windows!

The PocketShip has indeed gained a following. With stout and shippy good looks, delightful sailing performance, and micro-cruising comforts all rolled into one built-it-yourself package, it is a following that is well-earned.![]()

Jon Lee of Everett, Washington, is a full-time engineer, sometime amateur boat builder, not-enough-time sailor. He built his first boat, a self-designed rowboat, during grad school. In the years since, more boats followed, while Jon swore he could quit anytime he wants. His greatest claim to fame is successfully leading his boatbuilding team to two successive last-place finishes in the Edensaw Boatbuilding Challenge at the Wooden Boat Festival, and loving it.

PocketShip Particulars

Length: 14′ 10″

Beam: 6′ 3“

Draft, board up: 16″

Draft, board down: 36″

Sail area: 148 sq ft

Plans ($249) and kits ($3619, full kit) for the PocketShip are available from Chesapeake Light Craft.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I’ve already built one Chesapeake Light Craft kit (in my sixties) and can vouch for the high quality of the kits: design, engineering, materials, manuals, and customer service. Almost every summer weekend, I can be found out on Narragansett Bay, with family and friends, fishing for stripped bass, fluke, and scup on my beautiful CLC Peeler Skiff. Building and using my CLC boat has been one of the great pleasures of my life. My biggest problem is deciding which kit to build next. The PocketShip is definitely in the running when I retire.

Build a Swallow sail boat instead. I currently have a Pocket Ship and it is a hand full in 15 Knots, too light, not very happy with it. In hind sight I should have bought the Swallow Bay Raider 20, DAZ

Thanks for this issue!

I have been pondering my possibilities of building a small craft and for a long time have thought about the PocketShip and the Weekender, so finding articles of both yachts in the same issue has been a pleasure.

If possible, it would be nice to have an article about the Cape Cutter 19.

Regards,

Eduardo Fainé

I saw a Weekender in Poland. Lake was quite still but the boat was seriously unstable under power.

What I consider as the worthy successor to the late, great Peep Hen sailboat designed by Reuben Trane. John C Harris takes the basic concept idea of Mr. Trane and refines it. He has a terrific eye for small-boat design esthetic. I sure can picture spending time inside that small, inviting cabin for an overnight trip or two.

As a resident of Maryland and a fan,

Always great to review the designs and sailboats offered by CLC

What a beautiful boat! Nicely crafted, and very cozy. I really liked the article. Thank you for this.

“Another 150 to 200 lbs of ballast—bags of lead-shot—will later get set in the bilges of the completed boat.”

When you say set – do you mean set in epoxy? Am contemplating doing something similar myself in my ‘too light’ boat.

Water in plastic containers makes good ballast. Though it won’t provide the righting moment that you get from lead or iron , it has the virtue of neutral bouyancy in case of capsize or swamping. It’s also easily moved around to serve as trimming ballast.

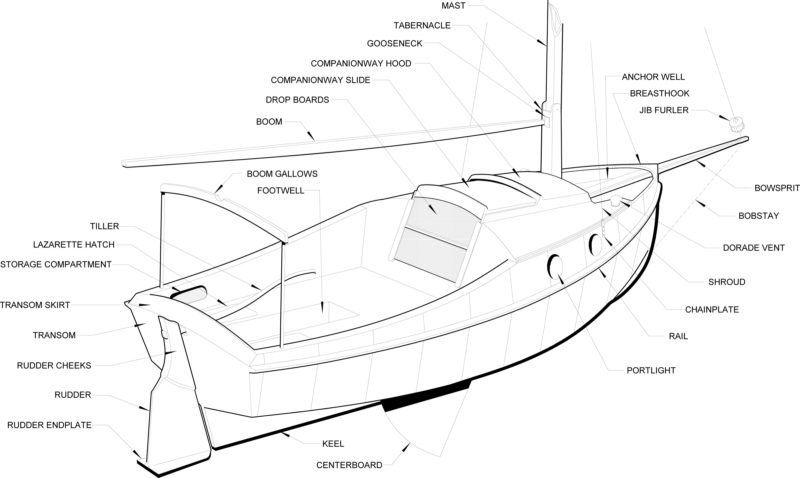

I see in the perspective view that there is an end plate on the rudder. Did you install this, and how has it worked out? Bolger ended up specifying such a rudder plate on virtually all of his shallow-draft boats.

Has anyone seen a version of Pocketship built without full cabin? I am curious about using the basic outlines and dimensions of this as a base for an open, centerboard, self-bailing/double bottom, single mast unstayed sailboat, with twin “bilge” keels instead of the shallow “v” …. thus hoping to see mods of this design if anyone has seen? Thank you.