Swallow Boats is a purveyor of boat kits in Wales. Their SeaRaider combines the best features of the fastest and most seaworthy Raid boats into one new boat. The boat originated in Scotland—one of the best places on Earth to put a small boat through its paces. In the space of a week on this country’s lochs and coast, one is likely to meet a wide range of weather conditions, from varied wind strengths, both upwind and downwind, to sudden rain squalls or katabatic gusts coming off the mountains. This drama is always complemented by enough soft breezes and sunshine highlighting the dramatic Scottish scenery to make one wish to stay longer.

The week of competitive sailing and rowing originally called the Great Glen Raid, now Sail Caledonia, has given Claus Riepe from Hamburg, Germany, and many other sailors, builders, and designers a unique opportunity to watch small boats perform under sail and oar and against each other. Any design or building faults, any glitches or lapses, soon become obvious. Claus thoroughly enjoyed the Raid concept, a week of competition and camaraderie in cruising areas that can be deep sea, shallow lagoon, or narrow canal, and he enjoyed his present boat, but he’d never sailed it in company with other boats of similar appearance. All week he and his crew had sailed their best and rowed their hearts out but were effortlessly overtaken by one boat after the other, always ending up toward the rear of the fleet.

Photo by Kathy Mansfield

Photo by Kathy MansfieldThe SeaRaider, a new design from the UK-based kit boat manufacturer Swallowboats, was purpose designed for point-to-point small-boat racing events called Raids.

“It was a sobering shock,” he admitted. “I first tried to upgrade with every trick I could think of—taller rig with more sail, carbon spars, booms, sliding fairleads—but all to no avail.”

He ordered a new boat, but that didn’t work either. Now ready for a complete change, he remembered Swallow Boats near Cardigan Bay in Wales, known for their small boats with a lovely sheer and performance, and their offer to design and build custom boats.

It was about this time that Matt Newland joined his naval architect father, Nick, at Swallow Boats, after a stint in London, bringing with him an engineering education from Cambridge University, designing skills on 3D CAD software, and the experience of working for a time with yacht designer Tony Castro. Claus visited them and described his dream boat, similar to a Drascombe Longboat but with better upwind ability, a self-tacking jib for singlehanding, room for four oarsmen on Raids, a mizzen that can be handled from within the cockpit, a strong rudder that does not have to be removed before beaching, good watertight stowage, self-draining ability, excellent buoyancy and righting capacity, and more.

The Newlands relished the challenge. Quickly they realized that water ballast was a necessity to achieve a light boat for rowing and racing, and a safe boat with self-righting capability for shorthanded sailing in varying conditions. After just two hours of discussion, a firm order was placed. All through the design process designer and client stayed in close contact, and together developed some innovative ideas and solutions.

The water ballast, for a start, is carefully thought out. “A false floor,” Matt explained, “is sited just above the waterline and inclining aft slightly, so the cockpit can self-drain through self-bailers or a simple twist hatch into the outboard well. A tank underneath this floor can take up to 660 lbs(330kg) of water, equivalent to the weight of four adults lying in the bilges.” Two inflatable buoyancy bags in the tank can be partly inflated to fine-tune the amount of ballast water taken on, a far more versatile system than multiple tanks. “And in effect,” Claus points out, “the boat has several different personalities. I can fish off the west coast of Ireland in a steady boat, or race with a crew in a light boat with its sail area of 196 sq ft and 21′ 10″ length for plenty of fun and excitement.”

There is an ingenious method for filling and emptying the tank. A forward-facing self-bailer within reach of the helmsman means the water can be flooded in, and three self-bailers mounted the right way around can remove it when the boat is moving as little as 3 to 4 knots. The water can also be pumped out with a conventional bailing pump, a small electric pump, or drained off as the boat lifts onto a trailer. I watched a capsize demonstration in Scotland when the water-ballast tanks were full: the boat self-righted so quickly from a complete knockdown that little water entered the cockpit and the crew were back aboard and sailing within two minutes.

Photo by Kathy Mansfield

Photo by Kathy MansfieldSeaRaider is water-ballasted. As this capsizing demonstration shows, the boat is extremely stable when in ballast. It self- righted during the drill, and the crew was back aboard and in a dry cockpit within two minutes.

Once Matt was happy with the design, he had all the plywood parts cut out by computer-controlled router. “This not only saves time,” he explained, “but also ensures the hull is designed accurately and fits together exactly.” She was built right-way-up over a four-mold construction jig. Her bottom panel is sheathed inside and out with heavy 16-oz (450g) biaxial glass, and the whole hull is epoxy-coated. The construction method is largely self-jigging and relies on internal structure like bulkheads to form the shape and provide stiffness.

Several custom-made pieces of stainless-steel hardware were commissioned for the boat, including the massively strong rudderhead (plywood blade), the tiller joint, and the mast tabernacle. Matt applied his engineering skills to the tiller design—always a problem when a mizzenmast is in the way. Under the aft deck a stainless-steel push rod with stainless-steel ball sockets at each end gives fine-tuned responsiveness without any slack. It feels slightly heavier than an ordinary tiller, but one quickly gets used to it.

The resulting boat is a modern classic, with the graceful looks and lines, lovely sheer, and elegant use of varnished wood for spars, gunwales, and slatted seats that are part of the ethos of the Swallow- boat range. It was important for Claus that they could both design and build his new boat. The SeaRaider has the lean shape and flat run aft of a racing dinghy of the 1960s, her transom narrowed to reduce wetted surface to improve rowing ability. Primarily she is a sailing boat; with a firm turn of the bilge, good form stability, and a flat run aft, she is well able to plane in the right conditions, as we found. She weighs just 716 lbs when the tank is empty, fully 440 lbs less than Claus’s old fiberglass boat of the same length. So, she’s lighter to maneuver, tow, launch, and retrieve, yet just as robust. The boat has an outboard well, sited inboard on the centerline where it should be, with a slit just for the propeller that simply closes with a flap when not in use. The maximum power is 5 hp, but a Honda 2.3-hp short-shaft is sufficient.

The boat, named CRAIC after the Irish word for a good sociable time, was so brand-new when Matt trailered her up to Sail Caledonia to test her, that even Claus had not seen her and was still sailing his old boat. I liked CRAIC’s slim shape and the versatile yawl rig that can cope with strong winds.

The gunter mast can be stepped or lowered down in its hinged tabernacle, its topmast and the mizzen spar being light carbon fiber enclosed in luff pockets like a windsurfer. This reduces turbulence on the leading edge and adds a bit more sail area, and CRAIC sails very close to the wind. The self-tacking jib is set on roller-furling gear and tacks easily with its club boom. For stowage, the mizzen wraps on its round carbon-fiber mast; the mainsail can be similarly furled if the gooseneck is disengaged. The sprit on the mainsail means that the spar is well above head height, yet the sail is well supported. Slab reefing is still possible, with cringles near the mast, or the main can simply be dropped. CRAIC rows well, her topsides are low enough, and the rudder slightly down gives directional stability. The thwarts are removable to clear space for sailing. Everything works so easily.

Photo by Kathy Mansfield

Photo by Kathy MansfieldSeaRaider’s gunter rig is easily un- stepped and stowed aboard.While primarily a sailing boat, she can be rowed handily when conditions require.

I joined CRAIC the day of her first real trial early in the week on Loch Lochy, on a crisp early summer’s day, the mountains circling the loch rising blue-green into the sky. The wind was gusty, between 8 and 18 knots, and designer Iain Oughtred had been invited to take the helm. The wind died as the race started but then returned strongly, and we set off on an exhilarating tacking duel with the Beetle whaleboat replica MOLLY, 6′ longer than our boat. Claus watched with incredulity as his new boat took off through the fleet “like a knife through butter,” he later told us, and left the rest of the fleet behind.

Our delight simmered down as the unsettled weather and the mountains began to throw longer and heavier gusts our direction, and whitecaps became trailing spume. Gusts up to 33 knots were coming our way, but Iain was curious to see what CRAIC was capable of and kept heading up, spilling a bit of wind when needed. We could have reefed the main, of course, or taken it down entirely; she sails well under jib and mizzen.

We turned onto the downwind leg, and Matt clocked 8.7 knots on his GPS before the boat with its four crew suddenly rose up a few inches and started planing. There was too much spray to read the GPS, but Matt had already reached speeds of over 10 knots in her in Wales. “It’s like a Nantucket sleigh ride, coasting behind a whale,” I thought to myself as I held on tight to my camera. At the next buoy we stopped to put in a reef, and by the time we reached our destination, the wind was an indolent breeze.

But CRAIC’s star had risen, Swallow Boats had achieved their biggest design breakthrough, and Claus was bursting with pride that he had been part of the project. Since then the boat has sailed in Raids in France and Italy, its design adapted to the BayRaider and cabin versions, selling through Europe and now to the U.S., and Claus’s pleasure has only increased.![]()

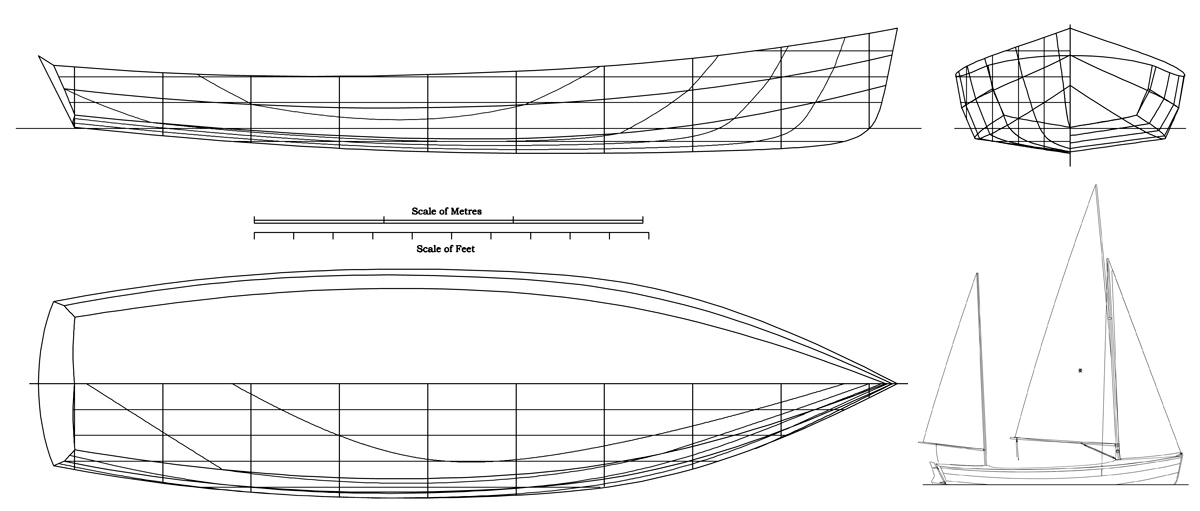

The SeaRaider’s lines show a narrow, easily driven, sheet-plywood hull that, due to its water-ballast tanks, is unexpectedly stable. The gunter rig’s spars are built of carbon fiber.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2010 and appears here as archival material. Swallow Boats is now Swallow Yachts and the Sea Raider is no longer in production. See their website for current models.

What a fantastic development story from the owner and Swallow Boats.

And the outcome is truly wonderful. Congratulations too to the journalist.

BUT, she is a very big boat for most of us single handers, and so it begs the question: Can she be downsized to 17 feet or so, and be as good or better than Swallow Boats’s existing fleet of great boats. Does she have advantages and points of difference worth having over the others that may now be incorporated?

John Shrapnel,

PERIWINKLE

I have sailed and rowed against this boat in Scotland and Cornwall and she is a cracker! My wooden Bayraider 20 PIPPIN is a foot wider and a couple of feet shorter so cannot quite keep up with her, but I will be back in Scotland in 2022 to try again.

The Bayraider 20, while gorgeous, always looks a little beamy to me. This hull looks just about perfect. It’s probably better for my pocketbook that they never turned it into production.

My epoxy ply wooden Bayraider 20 “Pippin”, weighing in at a mere 328lbs with 300kg of water ballast has proved fast, nipping at CRAIC’s heels on the final sea race of the Caledonia Raid.