In late August on a blowy afternoon of westerlies gusting to 25 knots, I set out in a small outboard skiff to run from an island retreat, across East Penobscot Bay and down Eggemoggin Reach—a trip of some 15 miles. As I departed the island, conditions appeared lumpy but manageable, but about a mile out it got unpleasant, with a nasty standing chop kicked up by opposing wind and tide. I knew I really had no business out there in a lightly built 16′ skiff vulnerable to being blown about in the gusts and smacked hard by the confused seas.

In spite of her light weight and moderate power (20 hp), my strip-planked Jericho Bay Lobster Skiff, PINK SLIP, handled the snotty conditions like the little lobsterboat that she is. Her straight keel prevented her from slewing in the seas, her fine entry kept her from pounding badly, and her flared bow sections knocked down the worst of the spray and had the reserve buoyancy to resist burying in the steep chop. I can’t say the trip was comfortable, but by throttling back and trim- ming my load slightly forward—weight redistribution is essential in coaxing the best out of any small boat— the skiff ran reliably and responsively in semi-displacement mode at 13 knots. I relaxed more as her seakeeping abilities became clearer, punching her into waves at higher speeds than I had initially dared. The boat continued to track well, responded promptly to the helm, and resisted bow steering, even coming down the wave backs. Boaters with better sense had already quit the Reach as I made my way down to Brooklin, feeling a bit foolish for being out in those conditions and lucky at my choice of boat. By the time I reached my mooring I had shipped only a few bailing scoops’ worth of spray.

This is a forgiving boat.

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyThe Jericho Bay Lobster Skiff seen here is a strip-planked, fiberglass-sheathed copy of a plank-on-frame hull designed by Joel White and built by Jimmy Steele in the 1970s.

The Jericho Bay Lobster Skiff was designed by Joel White, who built boats for most of his life in Brooklin, Maine. The boat was meant to be a work skiff for local builder Jimmy Steele (of peapod fame) to produce for local fishermen. Carvel-planked 14′ to 16′ boats of the general type were ubiquitous on Maine’s working waterfronts through the 1970s. There were regional variations and local builders with specific styles up and down the coast, but generally speaking they were tiller-steered outboard utility skiffs that would plane easily with 18 hp, dry out without fuss on the mudflats during a working tide, and safely carry a sizable load of clams, bait, or lobster gear between harbors at displacement speeds. They weren’t particularly high sided or broad, but they were fine tenders for larger working boats and were capable of working the bays and coves on their own in most seasonal conditions. Lobster skiffs were also the first boats local children learned to operate, tend a few traps from, dig a few clams from, and undoubtedly conduct a few adolescent misadventures in. Like any training boat, they benefit from having a tolerant demeanor.

Their graceful sheer and pinch of tumblehome leave little doubt that the best of them were modeled on the larger working lobsterboats of the area that had evolved to run efficiently with modest power in a range of sea conditions. While some larger Maine lobsterboats have successfully made the transition to composite construction, most of the skiffs died out starting in the early 1970s, just about the time Steele built a few of White’s design to test the market. They were replaced by the cheap-to-manufacture fiberglass or aluminum outboard skiffs that crowd today’s working piers.

In 2005 I chanced upon one of Steele’s original boats that had been squirreled away in a barn on Deer Isle, Maine, for at least 15 years. The owner had been a friend of Jimmy Steele’s son Jeff, from whom he’d bought the boat. He said the boat had been built for Jeff about 1970. She was a shapely thing, but I had no idea how she would perform, so I restored her parsimoniously, replacing fastenings and bending in new oak frames to stiffen some of the more limber stretches of the very dry cedar-on-oak hull. Crudely painted and powered with a borrowed 25-hp outboard, the boat confirmed that she was worth the trouble, so I finished her out and added a low steering console before buy- ing a new 20-hp four-stroke outboard (the weight of the 25-hp four-stroke was too much for the relatively narrow hull to handle).

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyThe Jericho Bay Lobster Skiff’s strip-planked construction requires no transverse framing. This makes for a remarkably clean and obstruction-free interior.

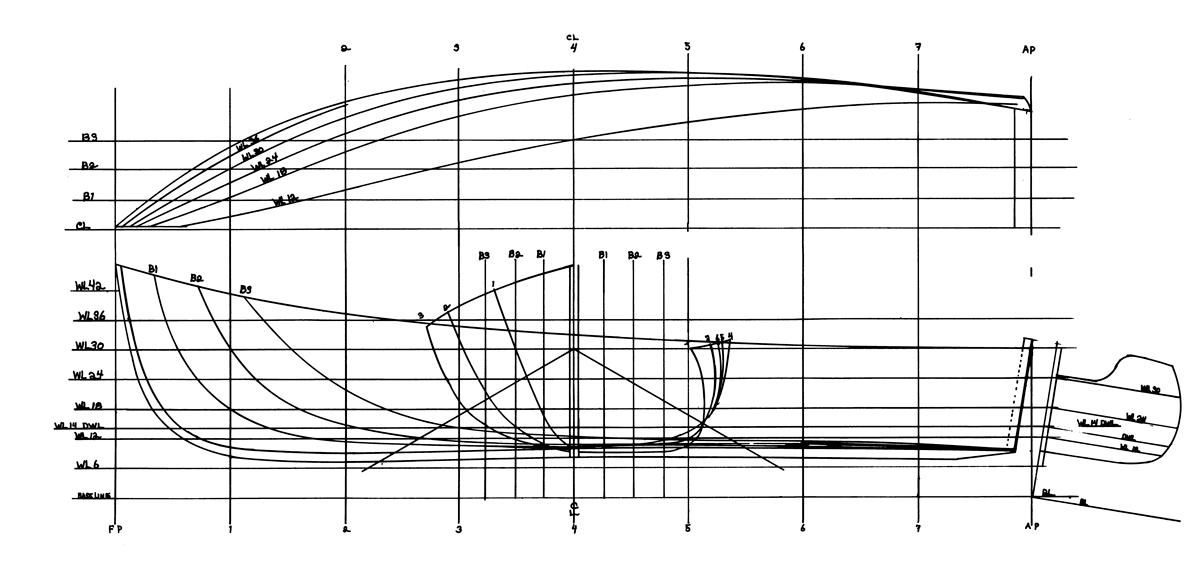

Two years later the volume of unsolicited compliments about the boat led boatbuilder Tom Hill and me to see if we could find lines for the model. They didn’t appear in the collection of White’s plans, but in conversation with Hill, Jeff Steele recalled seeing lines drawn by White when Steele’s father was building the boats. Jeff also solved a mystery about a noticeable reverse curve, or hook, in the after section of the skiff’s bottom. I had originally attributed it to distortion over years of storage on sawhorses, but Jeff said the hook was an intentional design detail that acted as a sort of primitive trim tab keeping the bow down and the boat running level.

In the absence of original drawings, Hill enlisted the help of Brooklin boatbuilder Eric Dow to take measurements from the hull. That done, Hill agreed to adapt the design for strip-plank construction. I was keen to have the same model in a version that was stiffer and more easily trailerable, and WoodenBoat magazine wanted to present a good-looking outboard skiff that could be built by ambitious amateur woodworkers.

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyThe horizontal steering wheel allows for easy access all around it, making steering possible from several stations.

Strip planking is better suited to taking the tight curves of the skiff’s bilge than the wide cedar planks Steele had expertly shaped with a specialized backing-out plane. After setting up molds, Hill constructed the new hull in 1⁄2″ × 1″ bead-and-cove strips of Alaska yellow cedar glued with thickened epoxy. (Details of his build were published in WoodenBoat Nos. 210 and 211.)

In an effort to eliminate the clutter and weight of frames inside the boat, we agreed to try applying heavy fiberglass laminates on either side of the cedar. Outside we installed 24-oz biaxial cloth in epoxy, while the inside skin is a full layer of 10-oz woven roving with a second layer of the same cloth over the bottom and up to the seat riser. We were still worried about the possibility of deflection in the flat sections aft when the boat was run- ning at speed. As a contingency we talked about installing a transverse bulkhead under the after thwart, but the heavy ’glass sheathing proved more than adequate.

My original skiff had all the scars and patina of years of use, including a set of deep grooves where lobster trap line had been hand-hauled over the oak gunwale. I’d cleaned it all up and painted it with a workboat finish, but there was nothing refined about it. My aspirations for the new boat were to repeat the paint scheme, but Hill offered access to a stock of beautiful mahogany that would have been a crime to paint over. So she was varnished into much more of a yacht than I had imagined.

The helm station, with a perfectly horizontal wheel atop a brass pipe, was a solution Hill came up with following long discussions in which he rightly determined that I didn’t want a boxy center console wasting valuable space in this small boat. By retrofitting an off-the-shelf Teleflex steering system with a shaft that would run up through the pipe mounted on a wide spot to starboard in the center thwart, he provided a helm that’s accessible to anyone sitting behind, beside, or even on front of it. This flexibility is very convenient when I’m running alone and want to adjust trim by moving my own weight forward. Often I run across the bay at 20 knots in a slight chop perched on the thwart next to the wheel with an arm draped over it, steering. It helps that the boat tracks superbly. By locating the helm pipe off center, I can fit a 14′ two-by-four in the 16′ skiff, something a big center console would preclude. The helm also looks striking, drawing more comments from passing boaters than the skiff’s more conventionally pretty shape and glossy finish combined.

I use PINK SLIP as an island tender. While she’s small for that task, in the three years I’ve had her I’ve carried loads of groceries, shingles, books, tools, and people in a range of conditions. I’ve only missed one trip that I might have made if I’d had a bigger boat. Of course, that statistic ignores the couple of times when I know I shouldn’t have been out there, which leads to what I still like best about her: She’s forgiving. ![]()

The shapely skiff is derived from the larger lobsterboats of the Maine coast. Slightly flared bow sections are beautifully balanced by tumblehome sections at the transom.

Plans for the Jericho Bay Lobster Skiff are available from The WoodenBoat Store.

Billy Atkin designed many boats intended for moderate speed (17 to 12 knots) and horsepower with the hook in the keel. Most of these, if not all, were for inboard power. Oddly enough, he never remarked on this design feature.

I believe it was Weston Farmer who used a similar principle in a 19′ lapstrake outboard he named TRUMPET. He specified 40 hp for propulsion. He referred to the hook in the keel as “empenage,” (a French engineering term, he said). The design appeared in one of the boat building magazines of the time, Sports Afield Boatbuilding Annual if memory serves.

The hook in the bottom is all well and good until your motor breaks down and you have to row home.

The hook creates drag, and makes rowing a chore.

I think a trim tab would serve the same purpose, and a hull without the hook to the bottom would get better fuel economy too.

Not so sure. A properly designed hook by someone like Joel White would improve fuel economy at planing speeds. As to rowing, the submerged planing transom rather than the subtle hook would make for drag. At slow speeds like that, the difference with or without the hook would be faint.