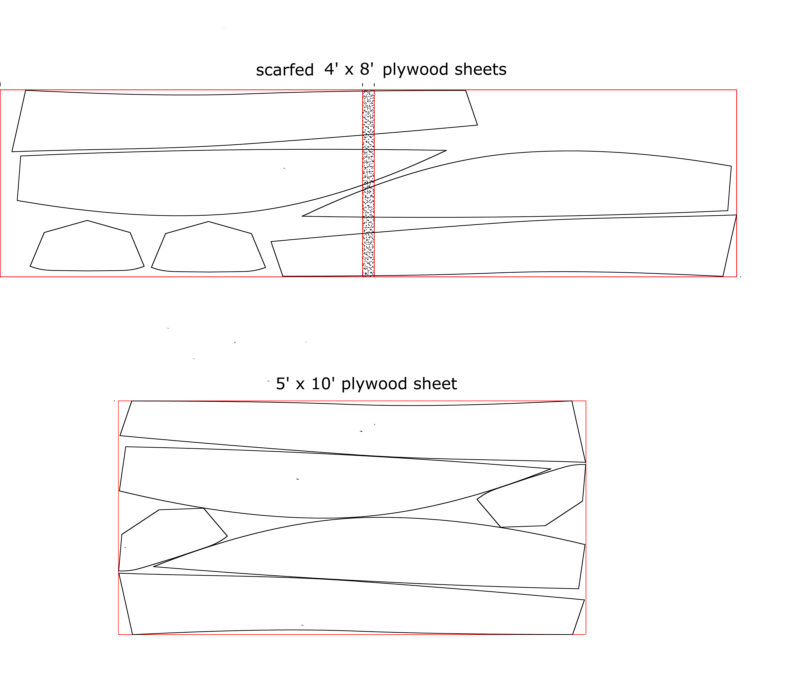

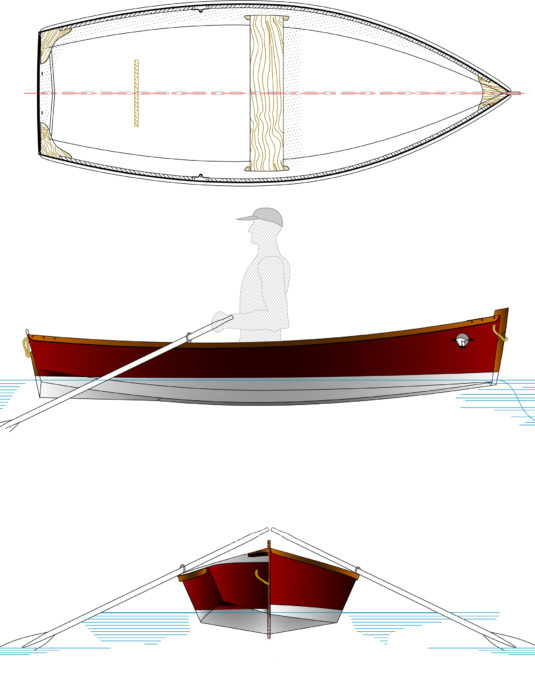

The Bella 10, Sam Devlin’s jaunty 9′ 9″ rowing skiff, started out being called the 5×10 skiff because all of the plywood it required could be cut from a single 5′ x 10’ sheet. When Sam was teaching boatbuilding classes, the 5×10 sheets saved him the time it took to scarf 4×8 sheets together to get the length needed for a small yet able rowing boat. There are a number of boats designed for a single 4×8 sheet of plywood, and while they are interesting as design challenges, they don’t have the length to be pleasing to row or the freeboard to carry an adult safely in a bit of a chop. The Bella 10 has both.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe interior is simple and spare, keeping the weight down. The foot brace called for in the plans, absent here, is essential for rowing.

Designed for stitch-and-glue construction, the Bella 10 can be built from plans or a kit. The plans consist of four pages of drawings that include the cutting schedules for a 5′ x 10′ sheet of 1/4″ (6mm) BS1088 plywood as well as for two sheets of 4′ x 8′ plywood scarfed together end to end. One marine-plywood supplier sells the 5×10 sheet of five-ply okoume for about $133 and the two sheets of 4×8 that would be required for $146, so you’d save a bit of money as well as the time required to scarf the two sheets together.

Devlin Designing Boat Builders

Devlin Designing Boat Builders.

The shapes for the side and bottom panels are determined by offsets measured from the edge of the plywood sheet, so the pieces all nest together and produce minimal waste. The transom gets two pieces cut, and they will be sandwiched together with epoxy at the start of construction. The drawings include a 24-step list of the building sequence, and an 80-page manual detailing stitch-and-glue processes is included with the plans. The book Sam wrote 25 years ago—Devlin’s Boat Building—is a good companion for those who like to study up before they build.

In the included manual, Sam details an alternative to the drilled holes and twisted wires in the stitches of stitch-and-glue: stapling the panel edges together. A pneumatic stapler with stainless-steel staples of the right length and gauge can speed the job of putting the panels together and have the added benefit of leaving virtually invisible holes after the seams are glued and the staples removed. Sam had students in one of his boatbuilding classes staple three Bella 10 hulls together; it took 25 minutes for the first, 20 minutes for the second, and 10-1/2 minutes for the third.

After the panels are stitched or stapled together, the hull is opened up to its proper shape with three spreaders while the seams are epoxy-tacked, have the stitches removed, and then get filleted and ’glassed. The exterior gets a layer of 6-oz fiberglass and epoxy to protect and strengthen the plywood. The remaining work is with 3/4″ hardwood lumber: 1-1/4″ inwales and outwales to stiffen the sheer, knees and a breasthook in the corners, an 8″-wide thwart and cleats to support it, and a low, glued-in foot brace. Flotation is provided by closed-cell foam blocks, easily obtained and cut from a throwable boat cushion, then screwed to the bottom of the thwart.

The Bella 10 I used for my trials was built by Devlin Designing Boat Builders as a showroom boat and impeccably finished. The foot brace and foam flotation were absent, and the sheer had the addition of a canvas-covered padded guard. At 52 lbs, the boat was light enough for me to carry it as I would portage a canoe. I rolled it over on the lawn, lifted the bow, and backed in to rest the thwart on my shoulders. Pulling the bow down raised the transom off the ground, and I could then easily walk with the boat. For transporting the boat with its oars and other gear aboard, my cart was a better option.

Hauling the skiff with a compact pickup truck is a simple affair, with no trailer to fuss with and no lifting to a roof rack.

The Bella 10 fit nicely stern-first into the bed of my half-ton pickup truck. The hull slipped between the wheel wells with a bit of room to spare, even with the bed-liner insert taking up some space. Not having to fuss with a trailer or lift the boat up to a set of roof racks was a welcome change.

The 52-lb Bella isn’t too heavy to cartop. Loading the boat is best done lifting one end at a time.

I could lift the boat to the racks on my Chevy Blazer, but it was an awkward lift approaching the racks from the side. The thwart is just above the boat’s center of gravity, so it makes a good handle for lifting and controlling the boat, but the boat’s beam makes it awkward when you’re on your own. It would have been easier to approach the back end of the car with the boat in canoe-portage mode, rest the bow on the back rack and the transom on the pavement, then lift the stern and slide the boat forward. I didn’t give that a try because I didn’t want to rasp the transom on the pavement or grate the canvas gunwale guard across my wooden roof-rack cross bars.

When I had the boat afloat, I first climbed aboard over the transom and later found it easier to step in and out over the side. About 8″ of water was enough to keep the boat from touching bottom when embarking.

With a beam of 3′ 8-3/4″, the boat was a bit nervous while I moved about, but settled down to be very steady once I got seated. I could slide on the thwart to about 6” from the side of the boat and look straight down into the water. That put the gunwale guard right at the water, as far as I could safely push the secondary stability.

A pair of 7′ oars is the perfect match for the Bella 10. They have just the right gearing and keep the stroke low.

For rowing, the thwart is in a good position relative to the oarlocks. I could sit well forward and keep my tailbone from pressing uncomfortably against the wood. With the foot brace omitted from this boat, I cobbled one together with a stick of wood, some rope, and a strap so I could row the boat properly and with full power. Once underway, I really liked the boat’s rowing geometry and the fit of the 7′ spoon-bladed oars. The handles had a 2″ overlap, right on target. On the drive, I could pull them straight at my solar plexus and have enough clearance over my legs on the recovery to avoid clipping wave crests. It was a nice compact and powerful stroke, far from the windmilling that small rowboats often seem to encourage.

Even though the Bella is just shy of 10′ long, it has a good turn of speed and is well suited to rowing for exercise.

The Bella 10 carried its way very well between strokes, easing the load at the catches, and it took very little effort to make 3 knots. At an aerobic-exercise pace I could sustain close to 4 knots and an all-out effort in a short sprint peaked just shy of 4-3/4 knots. I could row stern-first at 3 knots; and the transom didn’t seem to be bulldozing a big wave ahead of it.

The skeg does a good job keeping the Bella 10 on track without restricting maneuverability. The boat spins like a top and can do a 360-degree spin in just six push-pull strokes. In 1’ wind-driven waves taken on the quarter, the bow will occasionally veer, but the instant response to a corrective stroke sets the boat back on course. Rowing hard into an 8’-knot wind and waves just beginning to curdle before whitecapping, the forward end slapped some of the smaller waves, sending spray to the sides, but not causing the hull to shudder or slow down.

The Bella isn’t designed for use with an outboard—aside from the lack of buoyancy compartments that would be required, I suspect that my 2-1/2 hp four-stroke would be too much weight for the stern to support—but Sam and I agreed that an electric motor would be worth a try.

While the Bella 10 isn’t designed for power, the compact and lightweight EP Carry provided a satisfying push without overwhelming the boat with weight or excess power.

I borrowed an EP Carry from PropEle Electric Boat Motors, which I thought would be a very good match for the Bella 10 because it weighs just 21 lbs, including the battery. With the motor running at full throttle, the speed reading on the GPS wavered between 3-1/2 and 3-3/4 knots. Because I had to keep my hand on the motor’s tiller, I couldn’t get as far forward as I should have been to get the boat at its best trim, but I wasn’t doing the work, so it didn’t matter much.

I put my weight as far forward as I could and still reach the tiller. An extension would help get the bow down.

A tiller extension (built to accommodate the EP Carry’s atypical tiller) would have allowed me to sit comfortably on the thwart. Getting the bow down into the water would also help with steering. With it slightly airborne, the wind would hamper upwind turns. The boat has a Coast Guard plate on the transom noting that the boat has a maximum capacity of “2 persons or 300 lbs,” so having a passenger in the bow would allow a helmsman to be comfortably seated on the bottom aft of the thwart.

The Bella 10 is a splendid little boat that is inexpensive (it’s Devlin Designing Boat Builders’ most affordable kit), easy to build and transport, and an able boat on the water. It would serve well as a tender, a family boat for training young rowers, or an easily portable vessel for exploration and exercise.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Magazine.

Bella 10 Particulars

[table]

Length/9′ 8.5″

Beam/3′ 8.75″

Draft/6.1″

Displacement/305 lbs

Hull dry weight/52 lbs

[/table]

The plans for the Bella 10 are available from Devlin Designing Boat Builders for $27.50, downloaded, and $63.75, printed. The basic kit sells for $499 [6/25/20 on sale for 15% off, $424.15].

The plans for the Bella 10 are available from Devlin Designing Boat Builders for $27.50, downloaded, and $63.75, printed. The basic kit sells for $499 [6/25/20 on sale for 15% off, $424.15].

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Nice-looking boat, I see a market for those for kids to mess about in, socially distant rowing machine, or as an alternative to the fishing kayaks that are just getting heavier and heavier, some approaching 100 pounds. Nice to not need a trailer. Wonder if a pedal drive could be adapted?

The Bella 10 kit is currently listed at 15% off, $424.15