Paul LaBrie is new to professional boatbuilding, but the design he chose for his first commercial project is one of the oldest in this publication. CARPENTER was drawn up by L. Francis Herreshoff in the summer of 1929—his Design No. 41—and featured in his book Sensible Cruising Designs.

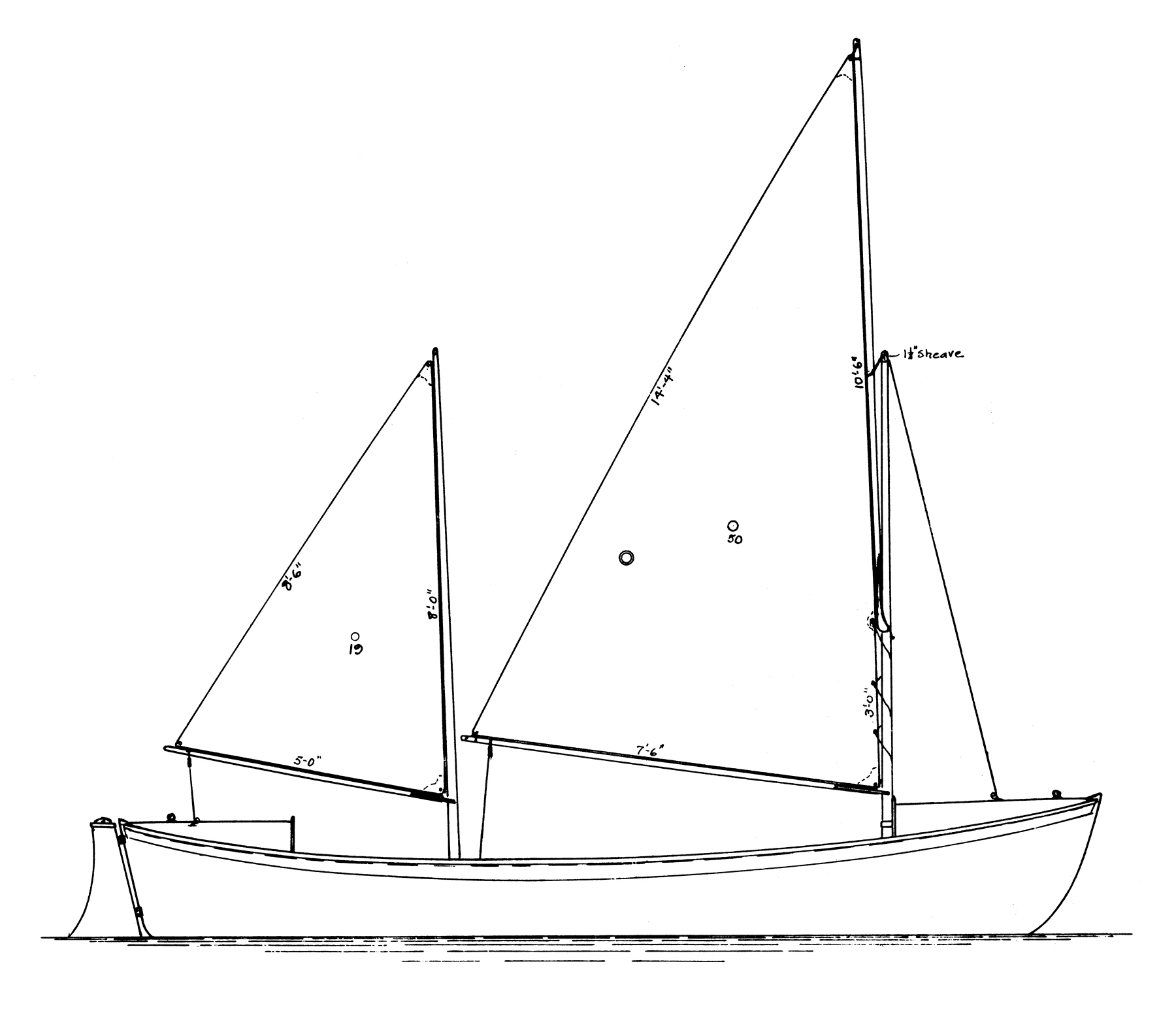

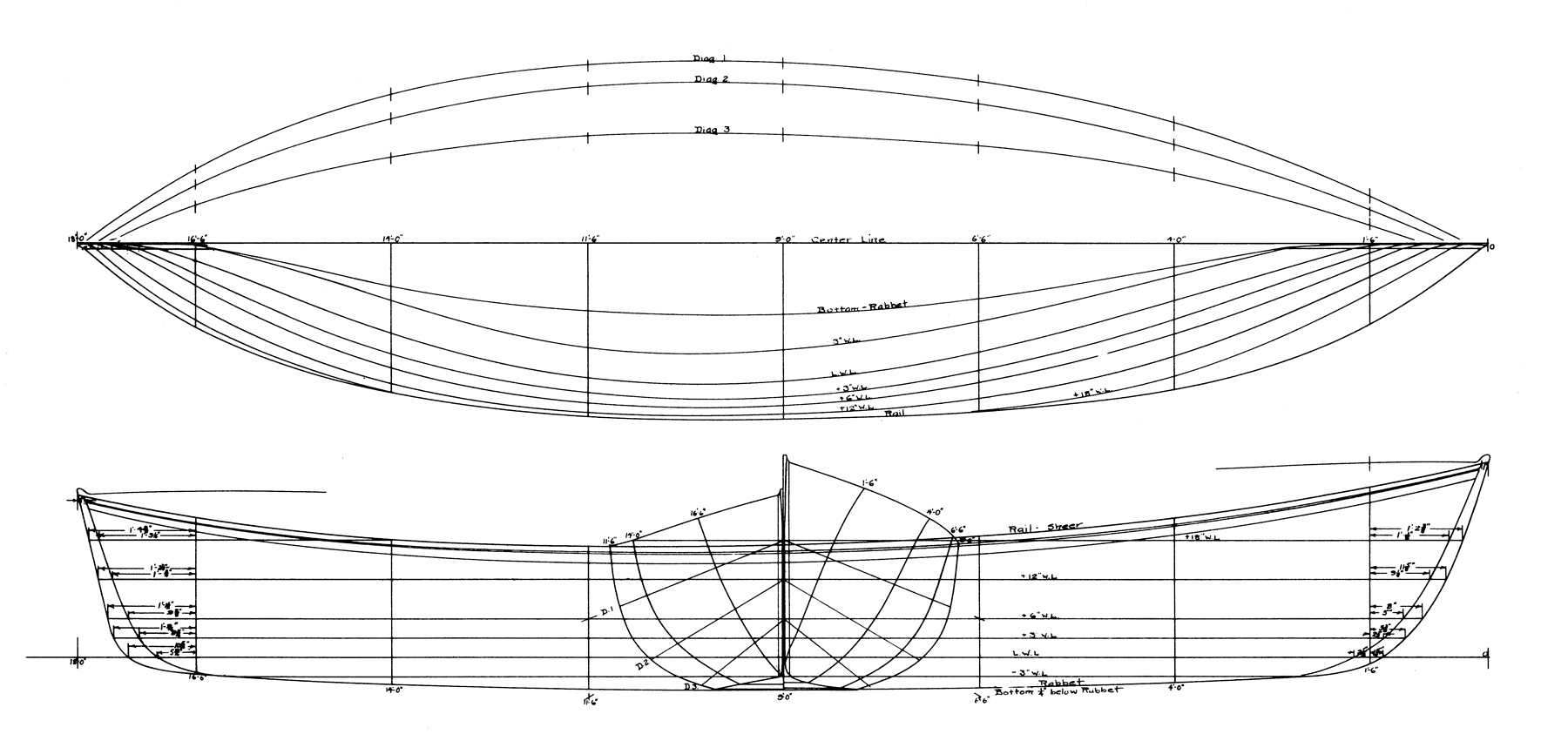

In an era when small boats were less commonly created for their own sakes, Herreshoff devised CARPENTER as a tender for the 50′ auxiliary power cruiser WALRUS. (The names come from Lewis Carroll’s poem “The Walrus and The Carpenter.”) He described CARPENTER as being a “sort of cross between a whaleboat and a dory, for she is whaleboat-shaped above the waterline, but has the narrow, flat bottom of the dory. The combination would make an admirable seaboat, whether loaded or light, yet a boat that would also take kindly to being beached.” He went on to explain that the “turtlebacks fore and aft provide dry stowage space and extra buoyancy,” and that “the rig is extremely versatile, for…there is an additional mast position at the forward end of the centerboard trunk, which would allow sailing her as a catboat with either the big sail or the small one.” In short, Herreshoff mused, “she would make an excellent secondary cruising boat for exploring small waters within range of the WALRUS’ anchorage.”

For Paul LaBrie it was love at first sight. About 10 years ago a friend gave him a copy of Sensible Cruising Designs and as soon as he saw the drawings for CARPENTER, he “just fell in love. I always thought, if nothing else, it would be a fun boat to have for myself. Then two years ago we moved to Maine—we have a log home in the woods with a barn and access to lakes, the Penobscot River, and the upper Penobscot Bay. Once I’d built the new shop it seemed that CARPENTER was ideal to be my first boat.” Paul had built boats before: an English punt for his son, two kayaks—one an Aleut baidarka, the other a “tortured-ply” Severn from a Chesapeake Light Craft kit—and a strip-planked canoe, but CARPENTER was the “first bigger boat” and the first to be built “on spec.”

Photo by Jenny Bennett

Photo by Jenny BennettThe characteristics that made the L. Francis Herreshoff–designed CARPENTER a fine companion to the power cruiser WALRUS for day treks also make her a fine daysailer and gunkholing boat.

I met up with Paul the day after his first sail in CARPENTER when, despite a few minor details that he felt needed attention, he was pleased with how things had turned out.

Just as he had surmised when first he saw CARPENTER’s lines, she is, indeed, a pretty boat. Double-ended with smoothly curving turtleback decks fore and aft, her sheer sweeps pleasingly from end to end and is picked up in each of her narrow lapstrakes. Her shape is reminiscent of the lifeboats seen on oceangoing ships of the early 20th century, but her construction is altogether lighter—with an overall length of 18′ and a beam of 4′ 6″, she has a total hull weight of just 400 lbs. Following the lapstrake building technique described in Tom Hill’s book Ultralight Boatbuilding, CARPENTER’s glued side planks are of 7mm BS1088 meranti plywood, while the single-piece bottom board is of 18mm meranti ply covered externally with Dynel fabric and epoxy mixed with graphite to give a strong abrasion-resistant finish in anticipation of the boat being beached. For the rest, Paul used native lumber: ash for the frames, seats, and gunwales, and white pine strip planks for the decks—these he built in situ before removing them to glass-sheathe them top and bottom. The decks have a pleasing smooth-radiused curve, which Paul thinks may not have been Herreshoff’s original intention: “I think he would have built them with a flat top and vertical board, but I think the curve is prettier.” Like the bottom board, both the centerboard and rudder are in 18mm meranti plywood finished with epoxy and graphite powder; the centerboard and lifting rudder blade are both weighted with lead pockets (the rudder follows the designed profile, but Paul made it lifting for beaching).

Photo by Jenny Bennett

Photo by Jenny BennettHer flat bottom makes CARPENTER an excellent boat for beaching, yet she has an elegant lapstrake appearance above the chine.

It’s always a treat to go sailing in someone’s new pride and joy, and when its performance lives up to the sweetness of the appearance, it’s a true joy. Paul and I embarked from his father’s dock in the upper reaches of the Piscataqua River on a day of little wind, yet we slipped right along, the chuckling of water against the narrow strakes a cheerful accompaniment to our conversation. Despite the strengthening ebb current (always an issue on this river that marks the southern border between New Hampshire and Maine), CARPENTER made good headway, and, as was to be expected given her light weight, she responded quickly to even the smallest breath of air. Paul told me that he’d heard criticism that the design is undercanvased—with the mizzen measuring just 19 sq ft and the main about 50 sq ft, it is certainly a small sail area, but judging by her progress that day I would have no qualms about it. Indeed, the reverse of the argument is that in a blow she could keep sailing when, perhaps, others of her size and narrow beam would run for shelter. For our outing we had set both main and mizzen. Sadly the wind never filled in enough to see how she fares cat-rigged with the main or mizzen mast stepped through the forward thwart, but I would expect her to remain well balanced. Under her ketch rig she tacked and jibed with grace, held a steady course on all points, and with no headsail to push her off, lay head-to-wind calmly and steadily whenever required.

Photo by Jenny Bennett

Photo by Jenny BennettYoke steering is necessitated by the centerline mizzensheet lead and works very well in a long, fine hull.

Inevitably with a new boat and an early outing we had one or two teething problems but with a bit of experimenting ironed them out. As we set off I found that she had rather pronounced weather helm, and this didn’t help me familiarize myself with the push-pull tiller. First I tried slacking off the mizzen sheet a couple of inches, and that did help but only with some loss of performance. Next we sheeted in both main and mizzen and raised the centerboard just a few inches—success! The helm was immediately lighter and, even when heeled to a gust, no longer a problem. The tiller did take some getting used to. For anyone accustomed to a conventional helming system it will surely seem awkward at first, but after awhile I did find that it became—if not quite second nature— at least logical.

Photo by Jenny Bennett

Photo by Jenny BennettWith her rig struck, CARPENTER rows and maneuvers well, with either one oarsman or two.

After a happy couple of hours’ sailing we returned to a beach by the Dover Point public landing and ran CARPENTER up on the shingle beach—just as she is designed and built to do. Her flat bottom now came into its own—she sits perfectly upright so that you can lean in and de-rig without grinding the topside lands into the beach. The masts and spars all fit within the boat’s length (one end of the mainmast tucked into the forward storage locker) so that you can row unimpeded, and trailer the boat without the need for support crutches. Once we were all tidied away Paul rowed around to the ramp, and within minutes CARPENTER was on the trailer and hitched to the back of the car—the ideal scenario if all you have time for is a short morning’s outing, or you’re lucky enough to be returning from a long weekend of camp-cruising with a friend.

L. Francis Herreshoff described his CARPENTER design as a cross between a dory and a whaleboat, flat-bottomed with well-rounded sides. Her rig is simple and versatile, with an alternative maststep at the forward end of the centerboard trunk for sailing single-masted when the wind pipes up.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2008 and appears here as archival material. If you have more info about this boat, plan or design – please let us know in the comment section.

Thanks for the “bonus” article.

I have read somewhere in the past, that Carpenter was the basis for the Sea Pearl 21, a great boat in its own right, of which I have owned three over the years. This is indeed a beautiful boat, but probably beyond my abilities at age 87.

Jim Brown

Sweetwater, TN

Paul, did I miss it? Wondering about the beam? Looks more slender than I thought she might be, but likely the photos. She looks like a perfect little cruiser for overnights up there. I’m leaning toward the ILUR, love the freeboard of both… but this little beauty might just change my mind.

Congrats,

Rob K

Hi Robert,

I no longer have the plans for CARPENTER so I can’t accurately speak to the beam, but CARPENTER is a long, slim boat as the photos suggest. Yes, Sea Pearls were inspired by this Herreshoff design, but they are much larger boats. (Dr. Denis Wang, whose Downeast Work Boat was featured last month in Small Boats, is the longtime owner of CARPENTER. The boat is now located in the Pacific Northwest).

I really like Vivier’s Ilur; it is a wonderful design and is a much different boat from CARPENTER. Ilur has the great advantage of being available as a CNC-cut kit and could be built more quickly.