Bill Hayward loves to explore rivers. His method for For the design of this boat, it is hard to believe that doing so involves the use of efficient and environmentally responsible propulsion, and his favored designer is Paul Gartside of Sidney, British Columbia. His first collaboration with Gartside was a 20′ pedal-powered boat, which he took on an 18-month journey from Alberta to the Gulf of Mexico, up the East Coast, into the Hudson River, then on to the St. Lawrence River and finally to Halifax, Nova Scotia. For his most recent voyaging boat— WAYWARD—he resorted to the use of an engine-powered 24′ 3″ hull that is also the result of a collaboration between owner and designer. Hayward wanted a boat for a journey through some of the rivers of the United States and eventually for a cruise on the canals of Europe. As of this writing, Bill had taken the new boat on the upper Mississippi from St. Paul, Minnesota, to St. Louis, Missouri. From there he traveled up the Illinois River to Chicago and into Lake Michigan. An overland trip by trailer took the boat to Halifax. The canals of Europe still beckon.

Photo by Wyatt Lawrence

Photo by Wyatt LawrenceAn easily driven hull needn’t be unattractive, as designer Paul Gartside has proved with WAYWARD, which relies on a 25-hp outboard for propulsion.

For the design of this boat, it is hard to believe that Hayward could have done better than to choose his friend Gartside. The designer and builder, who emigrated from Cornwall, England, to Sidney, turns out one lovely design after another. A visit to Gartside’s web site will give you some idea of the scope of his work, his attention to detail, and an extensive lesson in boatbuilding. Under “frequently asked questions,” for example, you will learn what books he recommends and you can read his detailed information on boring shaft holes, installing shaft tubes, strip and lapstrake planking, and leathering oars.

From the beginning, the dream and the reality of this boat had what this writer feels is an advantage over the majority of powerboats on the water today. The owner recognized the advantage of designing for displacement speeds. It is quite possible that the Earth’s atmosphere cannot support healthy human beings with the present level of pollutants being dumped into it. Our increasing use of fossil fuels for pleasure puts an ironic twist on the literal meaning of recreation. By traveling at 6 or 7 knots rather than at planing speeds, Hayward will easily double his mileage and thus cut his boat’s level of polluting in half. He finds as well that noise is minimized and comfort is optimized at this modest cruising speed, and he seems to get there just as fast.

In my own campaign to promote modest power and speed in boats, I frequently hear the argument that equates speed with safety. Specifically, the owner wants a boat that can hightail it for the nearest shelter when a thunderstorm bears down on him. This may be a good plan for the crew of an overloaded aluminum johnboat, but the weatherwise skipper will not be caught by surprise. A well-designed boat will allow him to ride out a squall in complete safety if not absolute comfort. This boat and skipper can take care of themselves.

Photo by Wyatt Lawrence

Photo by Wyatt LawrenceGartside’s client, Bill Hayward, favors cruising in inland waterways. He has already taken WAYWARD through the upper Midwest and was preparing to send her over to Europe for extended canal explorations.

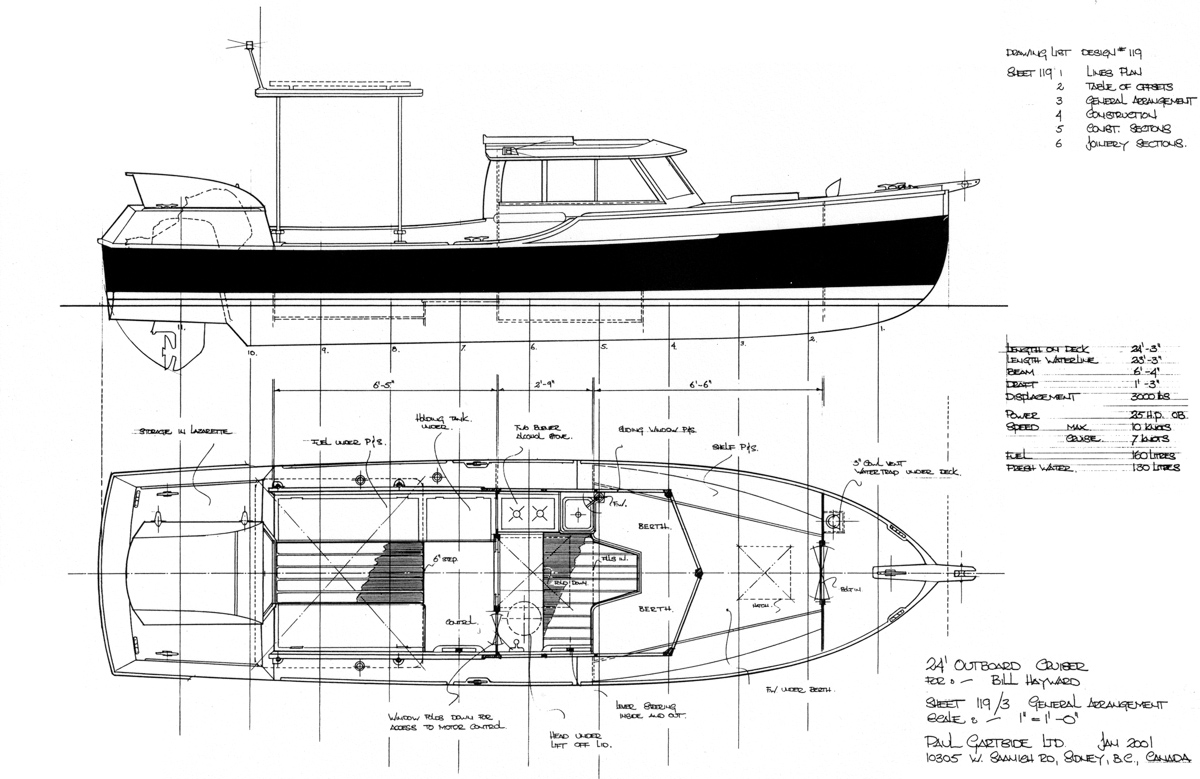

With a length of 24′ 3″ and beam of 6′ 4″, WAYWARD is narrower than average. This contributes significantly to her efficiency, allowing her to be pushed easily with a 25-hp four-stroke motor. The trade-off is a bit more rolling in a beam sea. This, according to the owner, has been an entirely acceptable compromise, since she was not designed as an offshore boat.

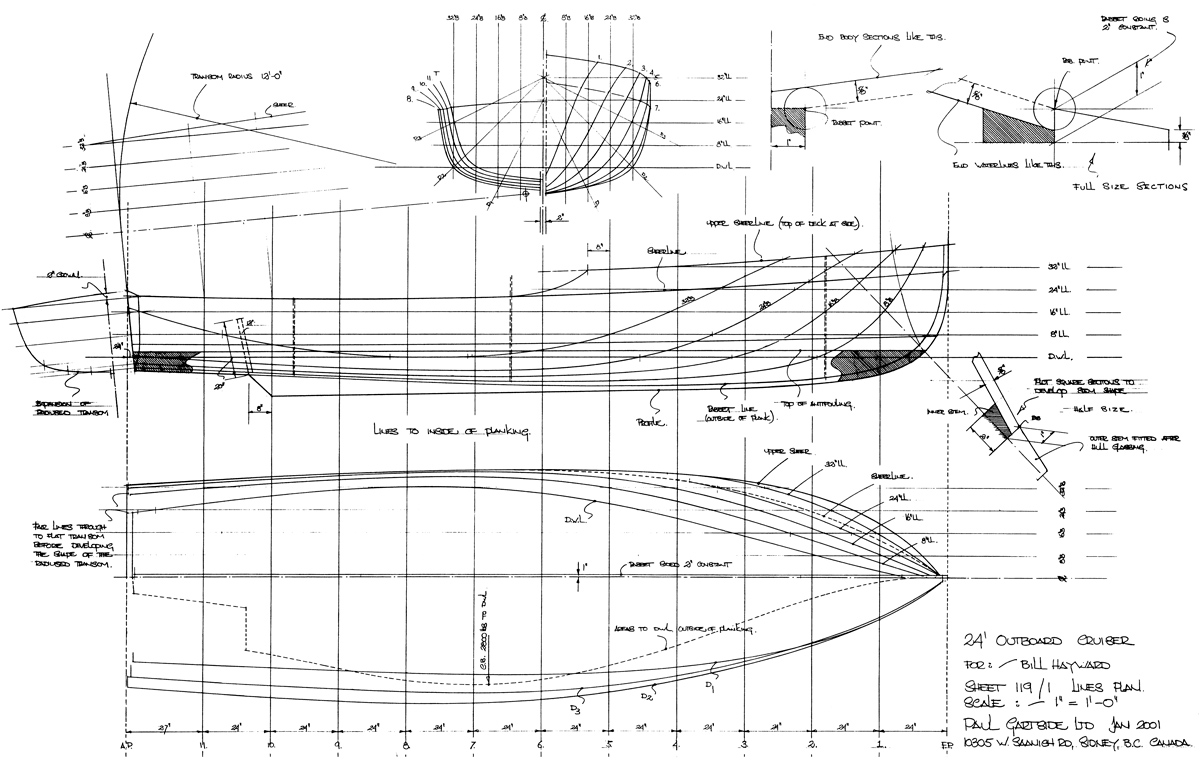

The lines show a fine entry. She will not slap and pound as she works upwind. The lines aft show a good compromise between running straight to a deeply immersed transom, as in a true planing boat, and rising to meet the transom at the waterline, which is the ideal for slow-speed work. The slightly immersed transom is narrow and will not create significant drag, yet it will provide additional buoyancy to hold up the motor and straighten the lines enough to give an extra knot or two of top-end speed.

The skeg extends below the hull a generous 8″ aft. This seemingly simple addition will be a big help in directional stability, but it can be hard to get right. Powerboats steer by swinging their sterns to port or starboard. If the skeg is square-ended and close to the engine, it will feed turbulent water to the propeller, causing it to race in a tight turn. The designer has given a slant to the aft edge of the skeg and called for a taper as well. The owner reports no problems.

WAYWARD’s hull is planked with 5⁄8″ strips of Western red cedar and sheathed inside and out with 17-oz biaxial cloth set in epoxy resin. As long as every care is taken to assure that water cannot penetrate the sheathing, this construction technique will allow the round-bottomed hull to go together relatively quickly and economically. There is no framing as such. Floors, bulkheads, and joinery combine to stiffen the hull. Decks are 1⁄2″ plywood, and the housetop is laminated of three layers of red cedar, eliminating the need for beams. Windows are made of 1⁄4″ laminated safety glass.

Photo by Wyatt Lawrence

Photo by Wyatt LawrenceAn enclosure keeps the four-stroke outboard out of sight, where its quiet operation won’t disturb the peace of a morning and where it won’t interrupt the lines of the hull.

A diesel inboard installation would have nearly doubled the mileage of this boat. It would be the best choice if efficiency were the only criterion, but the advantages of the outboard are significant. These include a considerably lower cost (particularly when the whole installation is considered), a quieter engine, and a more open cockpit arrangement. Diesel fuel is not always easy to find, especially when cruising inland waters.

A motorwell is always more complicated to build than an open-transom installation. One reward is quiet operation, and I’ll bet you can hear the bow wave as easily as the motor. Also, the well at least partially hides that big gob of technology perched on the stern. Motors ought to be tilted up when the boat is moored, in order to avoid marine growth in the cooling passages, and this is especially true in salt water. Failure to do so can result in expensive repairs. Unfortunately, WAYWARD’s engine rises when tilted, and the cover that encloses the tilted engine will be a big presence. The owner felt that the top section of the enclosure did not fit with the sleek lines of the hull and cabin, so he removed it.

Motors in wells often suffer from poor ventilation, causing them to stall, particularly when shifting at idle speed. When the boat is moving forward, exhaust through the propeller hub is carried quickly astern, but at idle speeds or in reverse, fumes can fill the enclosure. The designer has provided a vent hatch at the forward face of the well, a simple solution should this problem occur.

A low profile usually not only makes a boat better-looking but also reduces windage, so there is no attempt here to gain standing headroom under the shelter. A sliding hatch allows the crew to stand up while cooking. Steering is by either of two sticks linked together along the starboard side, one under the shelter and one outside. The preferred steering station is the after one, with the helmsman standing on a raised section of the cockpit floor. Stick steering is not quite as intuitive as wheel steering, but it has the big advantage (especially in a narrow hull) of taking up considerably less space.

Photo by Wyatt Lawrence

Photo by Wyatt LawrenceWAYWARD’s cockpit is well thought out for direct contact with the surroundings, and yet protection from the elements. Her accommodations are simplicity itself.

In the cockpit, four stanchions support an array of solar panels. The structure forms some shelter from the elements as well as convenient handholds in rough going. The owner has added canvas and clear plastic panels to this fabrication, adding considerably to the protection it affords. The solar panels were not as necessary as was originally thought, as the engine’s charging system was able to provide most of the power needed to keep the batteries topped up.

Fuel tanks located under the cockpit seats are generous because of the boat’s intended use and give a range of 220 nautical miles.

The short, stout bowsprit for handling the anchor makes great sense, particularly for a singlehander. The anchor can be set and retrieved from the cockpit if necessary.

WAYWARD’s accommodations are basic, and that’s as it should be. Complicated systems add expense, weight, and the likelihood of time lost to repairs. She has a generous freshwater tank under the V-berths, and a holding tank under the cockpit seat. A sun-heated shower has been a great comfort.

There is plenty of room for singlehander Hayward’s needs, although a couple undertaking his ambitious voyage would want to be a good fit. WAYWARD should be great for weekending and for day trips, and the grandchildren could nap peacefully to the sound of the bow parting the waves.

We have been obsessed with fast powerboats for so long that good efficient designs are hard to find. WAYWARD is a good example of what promises to be an exciting new era as we adjust to new environmental priorities.

Any designer has to balance the owner’s intentions with his own sense of proportion and style—and Gartside delivers on both counts with WAYWARD. The cabin echoes his larger powerboat designs while remaining in proportion and appropriate to the use. Accommodations are all that’s required and no more. Above all, she’s an easily driven hull that will be economical and stylish at the same time.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2008 and appears here as archival material. If you have more info about this boat, plan or design – please let us know in the comment section.

Are the plans available for this boat?

Yes, they are 390USD, and Gartside operates these days out of NY. This boat pops up a lot in reprints and such, though I don’t know that anyone else has bought one.

Are there pictures of a build and cost estimates and a bill of needed materials?

I have been on the hunt for this boat for years, so far the only pictures I have seen are from this article. Considering what it would take to bring this up to current standards, I would imagine a new design is required.

Cost is so variable, even without the threat of stagflation, that I can’t imagine how one would pin it down. If dry weight is half the displacement, then it might run 1500 pounds. At 4-8 dollars a pound you are looking at 6-12K for the structure. Start laying in epoxy and glass now, while prices are not unrecognizable.

“Construction is strip-planked western red cedar sheathed inside and out with 17 oz biaxial glass cloth and epoxy resin.”

I would estimate the surface area at 864 square feet, that is 24 x 6 x 8 x .75. So you can work out your planking and glass costs from that. Epoxy in ounces is similar to weight of cloth in ounces, though all these numbers are only the skin and the bare minimum, but if you can afford the “canoe” you should be be able to outfit it over the time it will take to do the work.

There are a lot of different ways to deal with the wood package. I recently got a lot of 1088 marine ply at sub garbage big box ply prices. Like 20 dollars a sheet for 1/4″. It turned out to be on the heavy side, but would be fine for something like this. But even at regular prices, the stuff was selling for a lot less that construction grade. And then there was some new pricing… which I am going to have to swallow some day.

If I was on the west coast, I would find a tree that was bothering someone and break out the chainsaw mill.

The story reports:

Unfortunately, WAYWARD’s engine rises when tilted, and the cover that encloses the tilted engine will be a big presence. The owner felt that the top section of the enclosure did not fit with the sleek lines of the hull and cabin, so he removed it.

I cannot figure this out. I don’t see where ‘he removed the top section’. The motor enclosure in the pix looks to be monolithic. Could you elaborate on this confusion, please?

I very nice craft in any case!! Keep this sort of thing coming.

If you compare the picture with the enclosure with the profile drawing, you can see the top portion of the well has been removed with a flatter top replacing it.

I think an alternative implementation would be to use a Nigel Irens (and many trad boats) installation where the motor is in a well near the pilot. One could get away with a tiller motor. Then retain the steering lever, but to control a transom-mounted rudder. Then you could have a toilet in an enclosure where there motor now is.

This is a great deal more efficient as you can have a sailboat hull shape. The downside being motor noise. I would just wear ear plugs if it got to me. Aren’t many people going to have their music on anyway? And for my canal use, I would probably run my 9.9.

You can find the Nigel Irens boats on Youtube, he was the inventor of the modern low-drag trimaran that wins so many races. But I have long preferred Wayward, from the waterline up.

I’m interested in how the stick steering was rigged. Is it a cable & pulley system or an adaption of a Teleflex or hydraulic setup?