Walter Baron, of Old Wharf Dory Co., designed the Lumber Yard Skiff (LYS) with commercial watermen in mind. It had to be simple, easy, and quick to build, and rugged enough to live at least 10 years in constant hard employ. He would build it of readily available materials—underlayment plywood for the topsides and bottom, clear spruce 44s for the stem and sternposts, and any suitable hardwood for the rails and shoes. Baron has since discovered that skiffs built with these materials have lived longer than he anticipated—and have done so without the benefit of coating the wood with epoxy. Paint on the outside, oil on the inside has been the rule, though some owners have had the outside fiberglassed.

He offers a 16′ standard LYS, a 16′ LYS Sport, and a 20′ LYS—plans or completed boats—and now prefers meranti marine plywood for the topsides and bottom and clear fir for the frames. He fastens the boats with stainless-steel screws and Sikaflex marine adhesive.

Baron, who’s been building boats for about 30 years, can knock together a LYS in about 40 hours, if he needs to hurry. A rank amateur with basic woodworking skills might double that time. When he’s finished, he’ll think that every minute was well spent, because the boat probably will exceed his expectations. Like most simple designs, especially ones that are easy to build, the LYS required more thought than we imagine. Baron took his inspiration from the Brockway skiffs, which were built by Earle Brockway in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, and well regarded along the coast from Connecticut eastward through Cape Cod.

Photo Courtesy of Old Wharf Dory Co.

Photo Courtesy of Old Wharf Dory Co.Walter Baron’s Lumber Yard Skiff is so-named because its materials can be procured from local lumberyards. The boat is rugged, inexpensive, stable, and meant for a variety of purposes—from fishing to recreation.

“I designed these boats using plywood models built to scale,” Baron said. “The sheer is the hardest part.” Even workboats should be attractive, so Baron took great care in getting the sheerline just right. Drawing an attractive sheer on a flat-bottomed boat isn’t the problem here. Having that sheer look right in three dimensions is another thing altogether—they can get all wonky. Baron solved this problem by making a model.

Working on the theory that wood—even plywood— will take its natural course when you bend it around a specific point, Baron established the shape of the topsides and the bottom at the same time. He wanted a fine entry so the skiff would provide a decent ride in a chop, and he wanted substantial beam aft to make it stable for hauling traps and to reduce the influence that shifting weight has on her handling. With these criteria in mind, he located the point of maximum beam well aft. A moderate delta shape is the result.

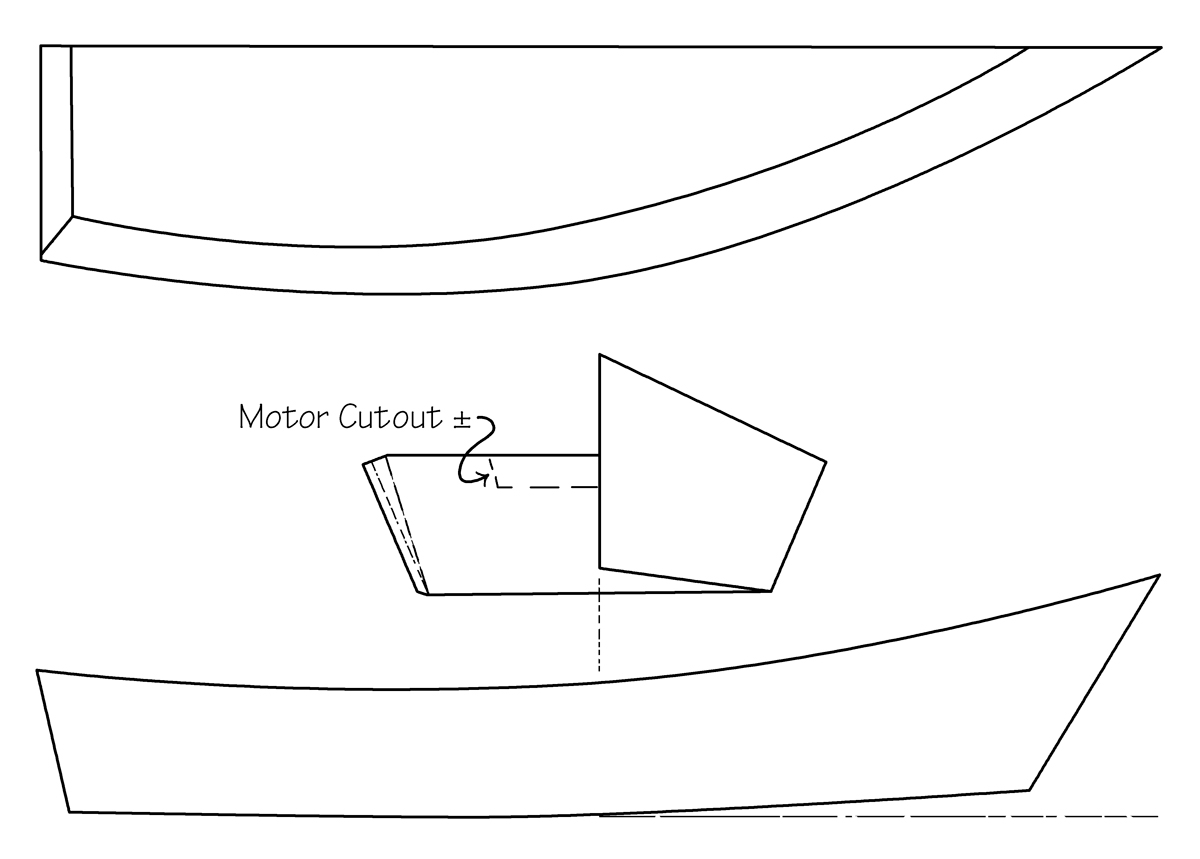

After he bent the plywood topsides to the shape he wanted, he had to determine the arc he’d have to cut into the topside panels, as they lie flat on the floor of the shop, to permit a gently rockered flat bottom. One way to do this is to scribe a straight line, bow-to-stern, on the topside panels when they’re bent around the spreader. This line will be perfectly parallel to a level floor The rocker (longitudinal curvature) can then be added. Cutting along this line gives the panel the exact arc it needs to fit the bottom to the LYS. After Baron was satisfied with the shape of the boat, he enlarged his tracings onto full-sized ply- wood sheets—two 1⁄2″ sheets per side on the 16-footer, and two-and-a-half 3⁄4″ sheets per side for the 20-footer. Baron uses butt blocks to make panels of the appropriate length. He got the stem and two sternposts from a single 12′ fir 4 4, the bevels of which he’d determined from building the model. Baron made the transom from two pieces of 3⁄4″ meranti.

Construction starts with the components assembled bottom-up. The stem and sternposts act as the buildingjig. You don’t need a strongback. Simply fasten the side panels to the stem and sternposts, install the transom, and insert the spreader. You’ll need a Spanish windlass to draw the topsides together, especially at the stem. Baron said that installing the chine logs is the most difficult part of the process, because bending them into the shape described by the curve of the topsides can crack the wood. Baron has varied the thickness of the chine logs to ease this process. His instructions will help you decide the proper dimensions.

After you’ve installed the chine logs, you’re ready to fit the bottom. Lay the plywood sheets in place and trace their shapes along the outside. Cut to the lines, join the pieces with a butt block, and the bottom is ready to install. Fit the hardwood shoes to the bottom, turn over the boat, and install the frames, knees, and rails. You’ll cut the side frames from 2″ X 8″ clear fir and the rails from 5⁄4″ X 3″ Brazilian redwood or other suitable hardwood.

Courtesy of Old Wharf Dory Co.

Courtesy of Old Wharf Dory Co.Construction is simple and straightforward; here, the after ends of the side panels have just been cinched in tight to the transom and fastened.

Of the 150 or so skiffs Baron has built, some of them have side decks and some don’t, depending on each owner’s preference. Side decks definitely add class to the overall design, especially if you varnish the coamings and rails or paint them a contrasting color. Clam diggers seem to prefer a deck, because it gives them a relatively stable platform on which to rest their buckets.

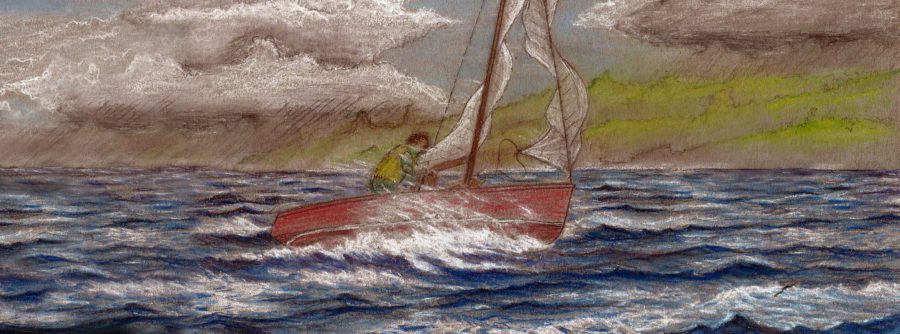

Side decks or not, the LYS has an unmistakable personality—a presence on the water that begs for attention. Baron and I got together for a short run aboard a 20′ LYS that’s owned and used heavily by a clam digger who works one of the plots granted to local watermen to raise and harvest clams. Moored bow-to in a slip at Wellfleet Harbor, proud bow standing clear of her “modern” plastic companions, she left no doubts about her purpose. Like most things designed around a function—the original Austin Mini of 1959, for example—the LYS gets under your skin. “What a cool boat,” I said to Baron.

Courtesy of Old Wharf Dory Co.

Courtesy of Old Wharf Dory Co.The plywood hull has been fiberglassed and inverted, and is being given side decks.

Her cockpit is nearly 21⁄2′ deep and makes a person feel safe. As I climbed aboard, I stood for a moment on the side deck. The LYS curtsied slightly and then rose to her level stance. Her flat bottom made short work of damping that tiny bit of roll there in the slip, and later in the confused seas and motorboat wakes of the outer harbor she proved to be equally adept.

Although the LYS is perfectly content at displacement speeds, she planes at about 12 knots and will stay on plane at about 10 as you back off the throttle. A 75-hp Tohatsu outboard powered my ride and could push her along at 20 knots or more in flat water. In the washing-machine conditions we experienced, exceeding 15 knots seemed foolish. As you can imagine, a flat-bottomed boat pounds in the rough stuff if you don’t slow down. On the other hand, the ride of the LY S 20 was good for her type. In the turns at speed, she leans in the way a V-bottomed boat does, just not as steeply. If you shift a substantial amount of weight to one side or the other, she will carve a turn on her chine the way a West Greenland kayak does.

Though I saw her only in photos, the LYS Sport 16 would be my choice if I ever decided to build a boat. Dressed up in a varnished mahogany steering console, bright rails and cockpit coaming, and with side decks and a relatively large foredeck (kind of an extension of the breasthook), she’s fit to carry her skipper and mate to the yacht club for dinner. On this model, Baron narrowed the transom a bit, which gave the LY S Sport a 4.5″ rocker (the standard 16 has a rocker of 2.74″ ). The bow is a little higher, too, and the package just seems more elegant. Baron charges $8,950 (less motor and trailer) for a fancy Sport 16. The bare hull is $3,250; plans are $50. A bare hull for the standard 16 sells for $2,650, and the bare 20 for $3,850. Plans for these are also $50.

Courtesy of Old Wharf Dory Co.

Courtesy of Old Wharf Dory Co.The completed skiff can be operated with simple steering, or a console can be added (see previous page).

I don’t know where you’d find such versatile, able, and handsome boats for less money spent on materials or less time spent building. The price of a new outboard—70 hp maximum for the LY S 20 with console steering, 50 hp for a tiller-steered 20; 30 hp for a tiller-or console-model LY S 16—will far exceed the price of the boat, even if you pay yourself at $50/hour shop time. Each model’s flat bottom and reasonable weight ease trailering, launching, and retrieving. The clam digger who loaned us his boat told me that he’s carried as much as 2,000 lbs of clams aboard his 20-footer. Other commercial users have related similar tales of exceptional payload, so you shouldn’t worry if you want to transport a crowd of family and friends to an island for a picnic. The LYS can handle it— and a whole lot of other jobs as well. When it wears out, take a chainsaw to it and build another one—you’ll still be ahead of the game.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2008 and appears here as archival material. Plans for the LYS are available from Old Wharf Dory.

Another lumber yard boat is the easily constructed, extremely stable, and inexpensive to build Brockway skiff designed and built by Earl Brockway of Rhode Island. My marine-tech classes built several of these with great success.

I have one of Walters skiffs, 20′. I love it. I am now down in Virginia on the eastern shore.