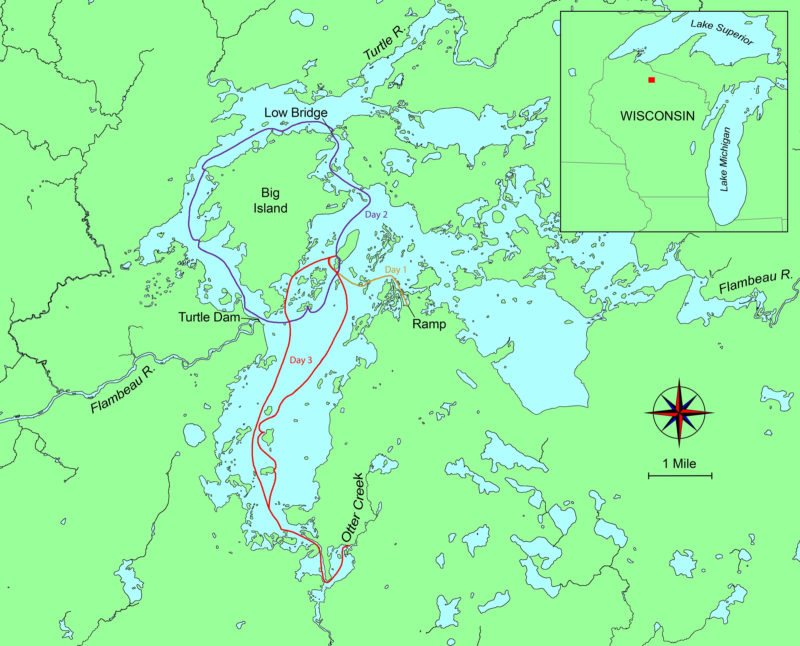

It was a Thursday in mid-June when Eric Vance and I brought our Chesapeake Light Craft Autumn Leaves solo cruisers to Cambridge, Maryland, at the mouth of the Choptank River. Our goal was simple: sail from the mouth of one of the bay’s many tributaries up to the farm town at the head of navigation. The weather here in the Chesapeake Bay area can be expected to take a turn to a calm, even sultry mood, and we expected to have leisurely sailing.

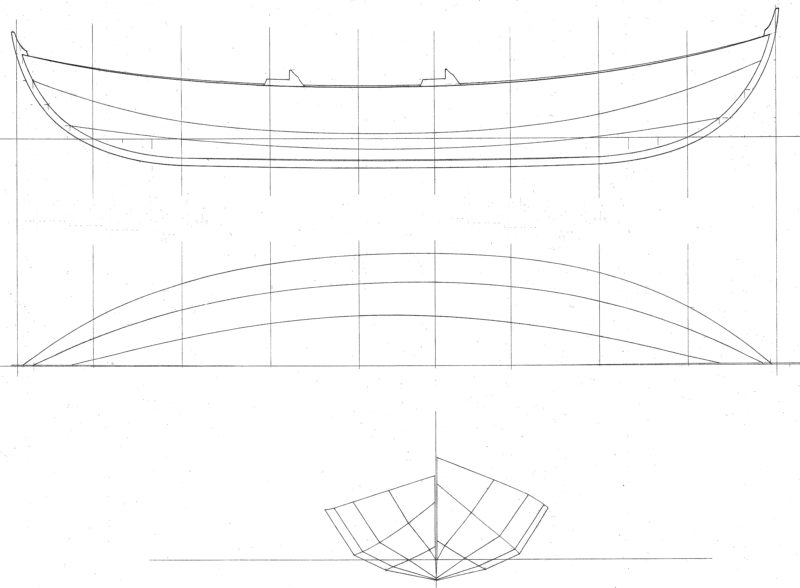

Sailing to the towns well upstream on the Bay’s tributaries was once routine. Travel up any of the many rivers that empty into the Chesapeake as far as a cargo schooner can go, and you’ll find a town. And in each of these towns, there are stories of the days when the schooners would sail in frequently, bringing goods from Baltimore and picking up wood, grains, tobacco, and other farm products to be hauled back over these myriad watery roads to the city. But what would it be like to do a motorless cruise up one of these rivers today? Eric and I wanted to find out.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

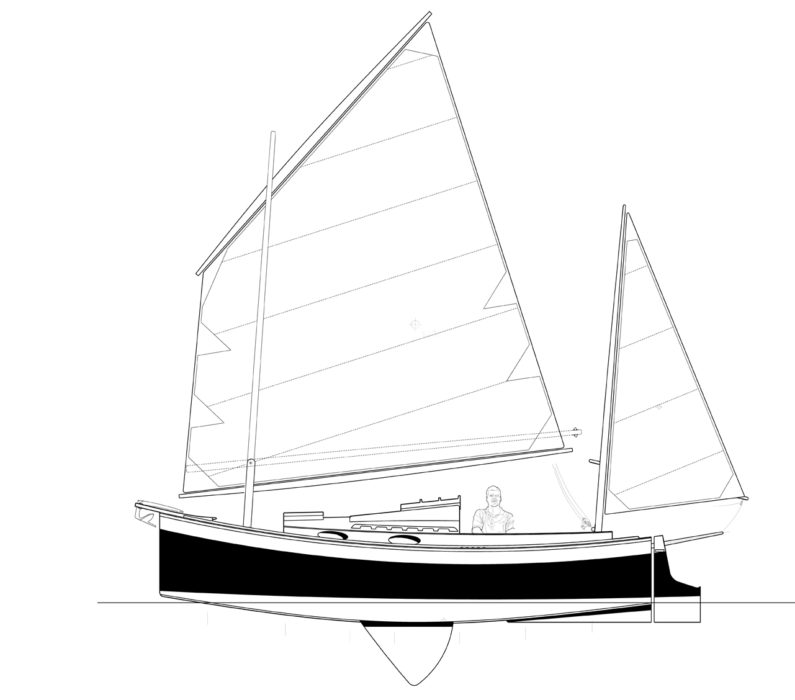

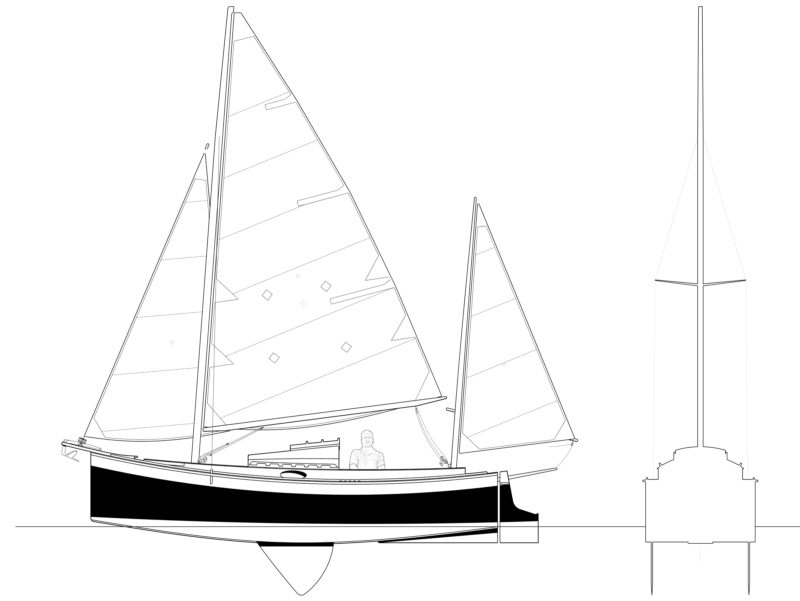

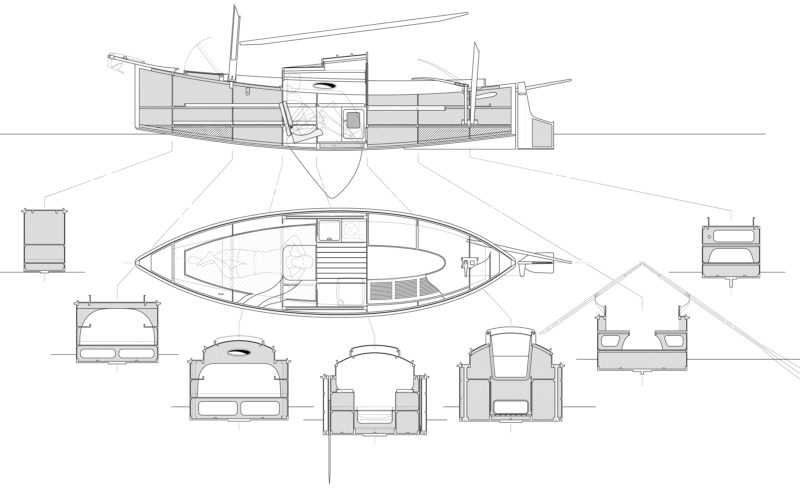

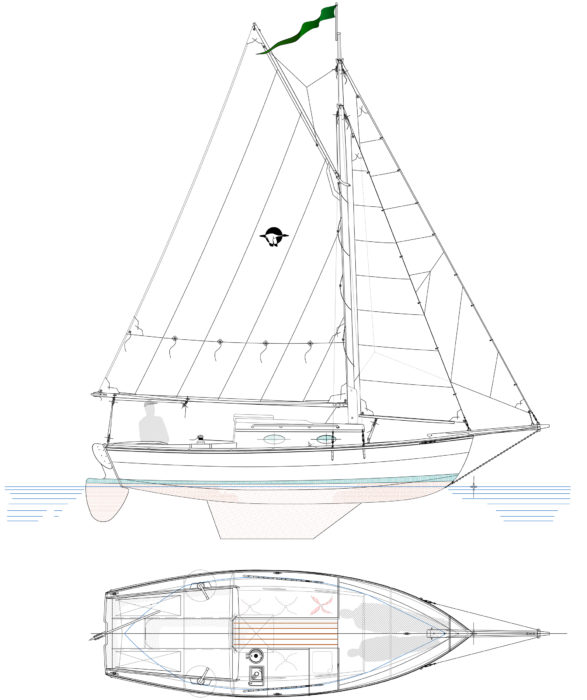

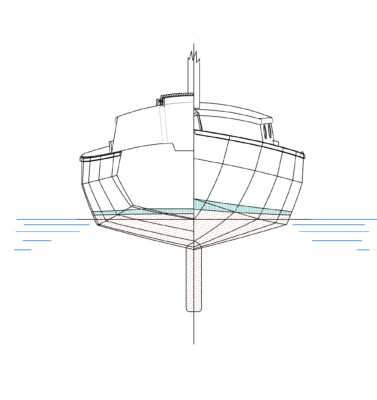

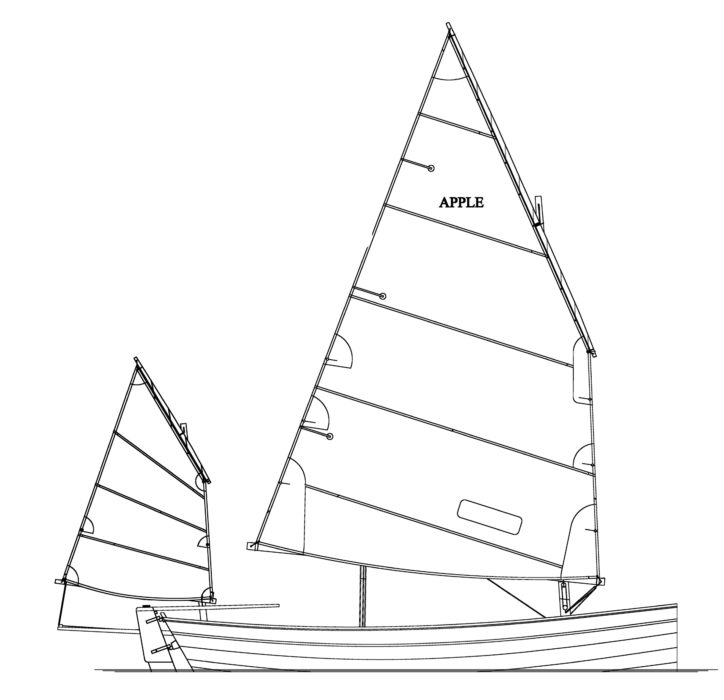

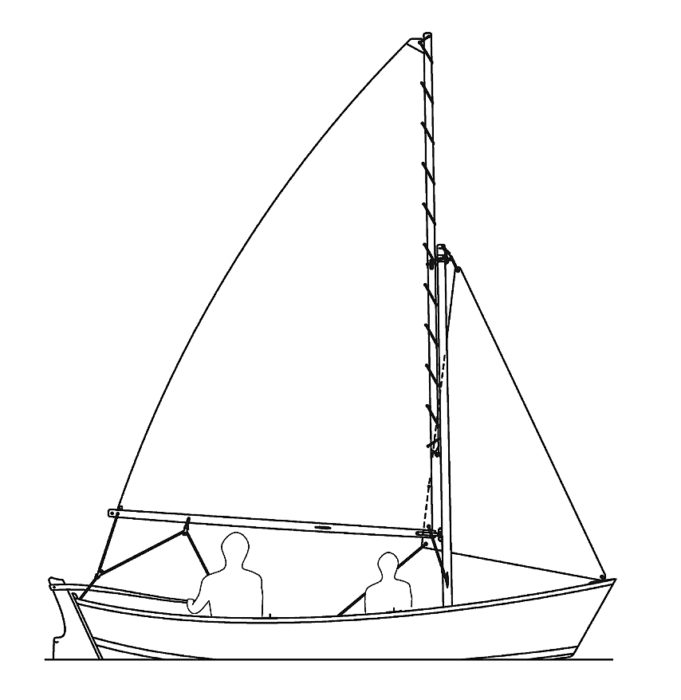

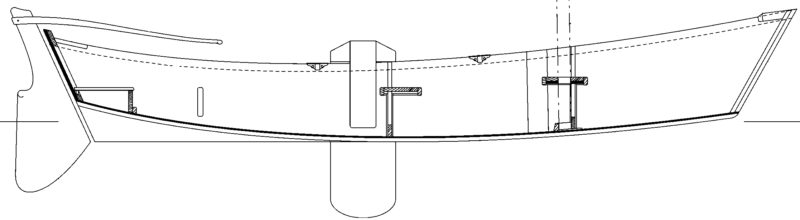

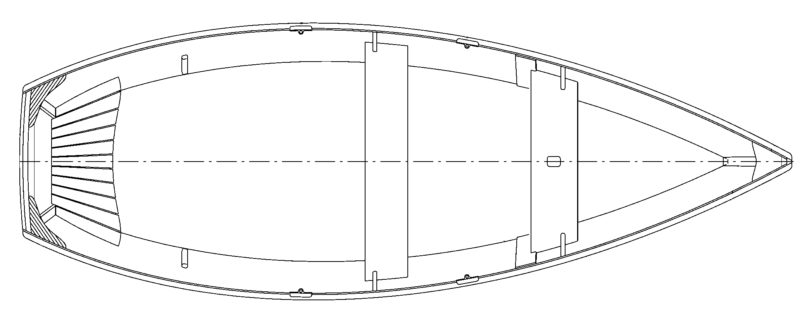

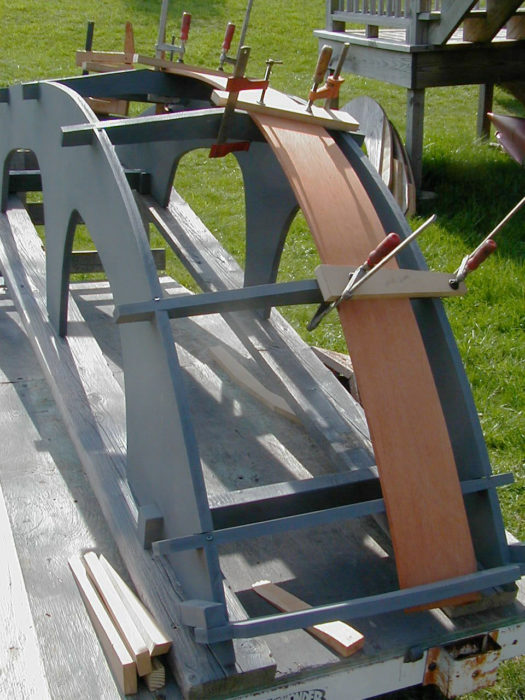

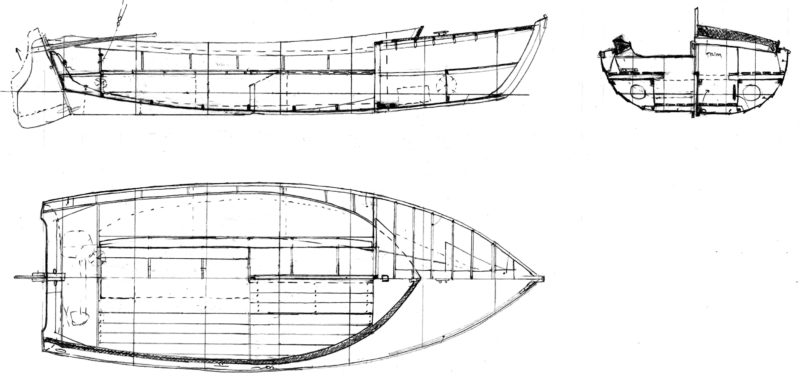

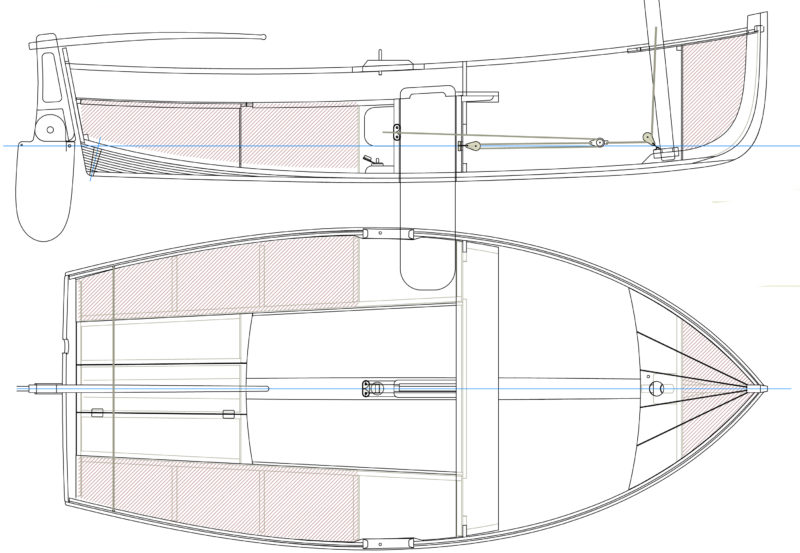

Our boats seemed suitable—shoal draft, nimble under sail, and easy enough to row, while having comfortable accommodations for overnighting. Eric’s boat, INDIGO, had no motor, so he was fully committed to oar and sail. Mine, TERRAPIN, has an electric trolling motor on a bracket, but I was determined not to use it.

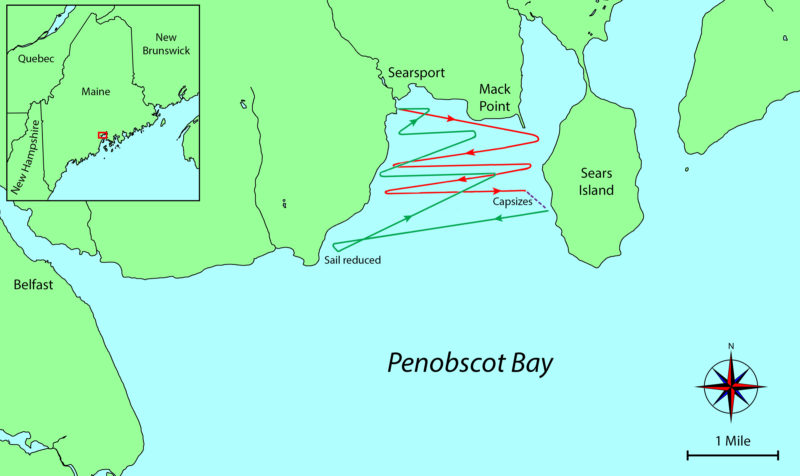

At the Choptank’s mouth: Cambridge, seat of Dorchester County and historically one of the principal ports and boatbuilding centers on the Chesapeake. Upriver, at the head of navigation: Denton, seat of Caroline County and through the 19th century a major export point for lumber and farm produce. With 35 winding miles of river between the two ports, it promised to be an interesting challenge for a four-day weekend.

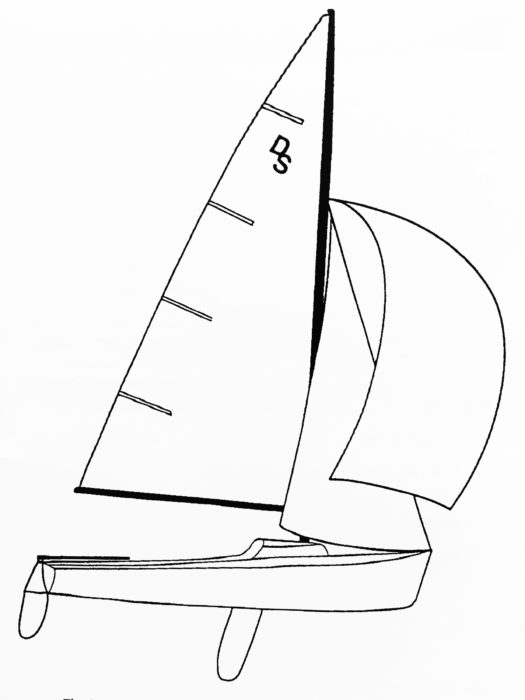

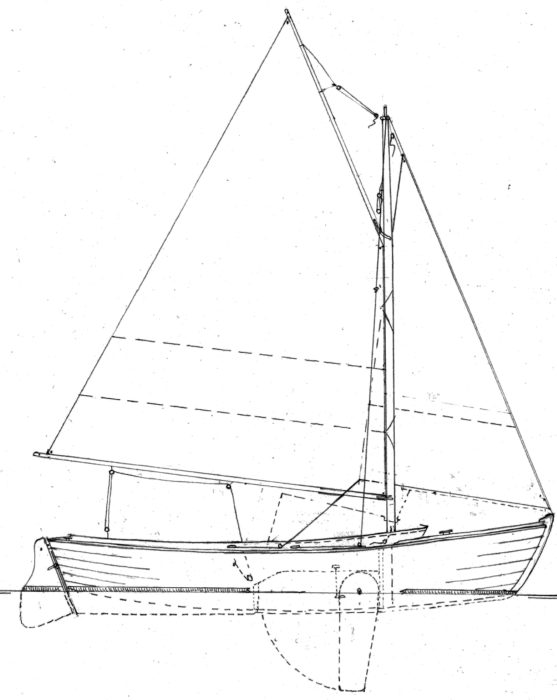

At the ramp on Cambridge’s Eaton Point, where we were preparing the boats to launch, the wind was brisk and out of the south—a wind advisory had already been broadcast. While TERRAPIN was still on her trailer, I tied the second reef in her 150-sq-ft balanced lugsail. Eric was ahead of me, having already put the second reef in his 114-sq-ft jib-headed main.

All photographs by Eric Vance

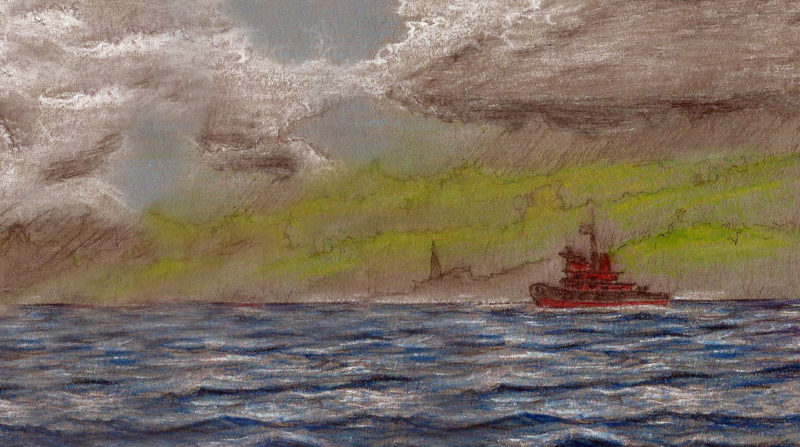

All photographs by Eric VanceTERRAPIN showed all the speed she can muster, double-reefed on her way up the Choptank. A small-craft advisory was posted and would remain in effect for days to come.

Once we got under way, we scudded to the northeast on a reach and passed under the 1-1/2-mile expanse of the Route 50 bridge, a gently arching ribbon of concrete girders resting on countless cylindrical piers, and 50 yards farther on, through the gap in the old Harrington Bridge, now a pair of fishing piers. A chop was just developing mid-river. The starboard bow caught the bigger waves, tossing spray into the air, and once or twice, the cool water found my face. It was exhilarating. Less than 2 miles beyond the bridge, we veered north and with the wind now at our backs, everything quieted down. The boats’ motion eased. The weight in the helm, the solid chunk and thump of the wooden hull slashing across the chop, and the strain in the rigging all melted away as we eased the sheets to follow the river through its left-hand sweep. We passed large homes with expansive, immaculate lawns spread along the riverbanks. Signs of the city and highway rumble dropped away.

A few miles on, beyond the outskirts of Cambridge, the estates disappeared and the houses looked like they had been here for quite some years. The river was bounded almost entirely by marsh and woodland; breaks in the trees revealed farm fields beyond the banks. This time of year, the winter wheat is tall and ready for harvest; the corn is just getting a foothold across this low-lying, verdant landscape. In this low country, the subtle irregularities in the horizontal landscape give way to an immense arching, hazy blue sky.

The tide was with us. Our narrow yawls held between 5 and 6 knots hour after hour, churning up fine, frothy bow waves and leaving easy, flat wakes behind their double-ended hulls. As we carved our way up the river, it narrowed, and the nascent chop of the open stretches was left behind. Now, just smooth, easy speed as we slid past the bright green of the saltmarsh cordgrass backed by the mottled and darker greens of the scalloped treeline. The Chesapeake water is usually the color of lightly creamed coffee, but as the day progressed, the sunlight played games over the river—a soft tan coloring the corrugated surface one moment, reflecting the blinding, unfocused glare of an old mirror the next.

A thin cloudbank slid in from the southwest, turning the sun into an orange smudge, softening the riverscape’s textures and muting its tones.

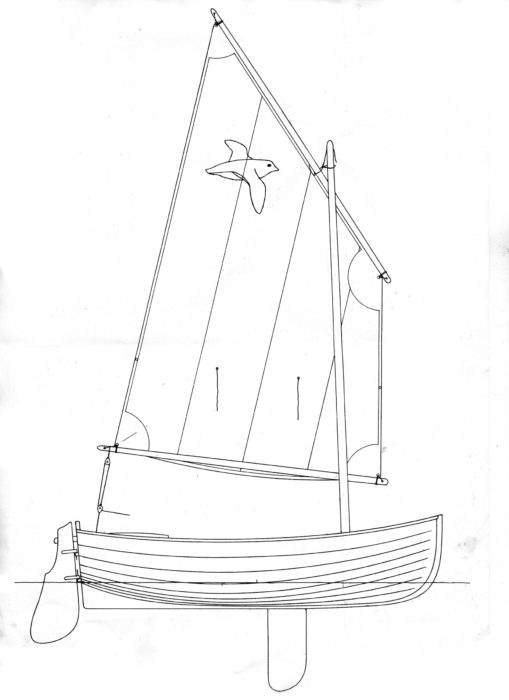

On Thursday evening, I settled in after anchoring in Hunting Creek. We found quiet anchorages in creeks like this one all the way up the Choptank River.

We were making good speed but were in no hurry. When we reached Choptank Landing, we swung east into the mouth of Hunting Creek and nestled into a small cove next to the low bridge that leads into the village of Choptank. The north-facing cove shielded us from the bluster out on the river, and we were well situated for a relaxing evening. A turtle, likely a terrapin, poked its thumb-sized head above the water for a moment. Schools of finger-sized fish churned the surface—first off the bow, then to port, and again by Eric’s boat. To the east, a mourning dove endlessly cooed its low, sad five-note tune. On the opposite bank, a Carolina wren sang its lively soprano trill.

At the anchorage in Hunting Creek, I watched the sun drop. It was just before the summer solstice, and the days were long.

The ever-changing light over the Chesapeake is one of the things that attracts me to the bay. Here, at about 8 p.m., a golden hue is cast over the landscape.

At day’s end we retreated to our snug cabins. We weren’t troubled by biting insects and could leave hatches open through the hot nights.

Friday morning, we rowed over to Choptank’s marina, a modest 70-slip harbor protected by wooden bulkheads. There once was a wharf here, one of many built along the length of the river. The banks of the Choptank are by-and-large low and muddy, often banded by marsh that could not be traversed by horse or cart, so where there was a stretch of solid bank next to deep water, as there is at Choptank, schooners of the 18th and 19th centuries could deliver and load goods.

We tied up and took the opportunity to stretch our legs. A few kids were swimming at the tiny crescent beach next to the marina, but otherwise it was quiet. It was approaching mid-morning and the wind was building out of the west. TERRAPIN, like INDIGO, is well-ballasted and displaces about a ton, but when I stand to row, I can put all my weight into the stroke and get the boat moving. With some effort, we rowed free of the marina and got our boats into deeper water, clear of obstructions. With mizzens set taut to hold our small yawls head-to-wind, we raised sail and were soon able to bear off, under sail once again. Below a blue sky becoming washed by a developing summer haze, the wind was nonetheless brisk, offering relief to temperatures already in the high 80s. We wore light, long-sleeved shirts and wide-brimmed hats. Eric pulled an orange and black bandanna up over his nose. The glare of the sunlight glancing off the river surface was blinding. But the sailing? In this wide, open stretch of the Choptank, the drive was solid and steady; our boats dug in and took off with vigor.

As we approached Frazier Point, the tide was beginning to ebb and we were forced to cover a short leg straight into the wind–a wind that had now become unsure about its speed and direction. Our two Autumn Leaves are rigged differently but sail almost exactly the same. TERRAPIN, with her big standing lug main, shows some advantage downwind.

INDIGO’s jib-headed yawl rig gives her an edge into the wind. But when we attacked the 100-degree bend around Frazier Point, working to clear the point and fall off onto an easy reach, Eric edged well ahead of me, putting more than a quarter mile between us. (That evening, I learned that Eric, a whitewater canoeist well versed in reading currents, had spotted a broad, gentle eddy circling behind Frazier Point, slipped into it, and let it pull his boat halfway around the bend.)

As we headed north, the cordgrass gradually gave way to marshlands with a mix of reeds that thrive in the brackish upstream environment of estuaries. Up ahead, two watermen in an outboard skiff were working a line of crab pots. Their voices and the putter of the motor broke the stillness of the day. We had seen very few boats on the river, which was not my experience in other parts of the Chesapeake. As we followed the river around another bend, the wind jibed the main to port, but left the mizzen out to starboard. I was sailing wing on wing. The Chesapeake schooner captains sometimes called this “reading both pages.”

It was early afternoon and we had reached the bend around Hog Island, a low marshy headland on the inside of a long, quarter-mile curve in the river. On the outside of the bend, the river has carved itself into a high bluff topped with a line of trees. The tide was now driving against us with authority: our tacking angles felt good, but we were barely advancing against the building current. A red buoy marking the starboard turn in the channel teased us–it refused to get closer despite our best efforts to advance on it. I hailed Eric on the VHF and suggested nosing into the steep left bank to escape the wind and take a lunch break. He was quick to agree. Once his hook was set, I dropped sail and rowed over to tie up alongside. As we lunched, a bald eagle glided by. The heat built to 90, then 94. Cumulus clouds formed overhead but offered scant shade. We sweated it out, waiting for the current to abate.

I rowed TERRAPIN around a shoal on the way to the town of Choptank. Contrary to the forecast, the air was calm early in the day.

At 3:30, we decided to get going. Eric commented, “At least it’s not so hot.” I checked my thermometer. “No, still 94. You’re just getting used to it.” The wind was building back to the unvarying forecast: northwest, 15 knots with gusts over 20. We still had the double reefs we’d tied in at the ramp, and we’d leave them in.

Once we cleared the bend around Hog Island, the banks opened up and a tailwind, channeled by the local geography, found its way down to the water. TERRAPIN and INDIGO took off. I was initially ahead, and looked back to see INDIGO throwing up a thick and frothy bow wave, a big wide mustache of water breaking across the river. She heeled to the breeze, her three sails taut and trimmed to perfection.

The breeze freshened further. We were sailing our little cruisers like racing dinghies, sheet in one hand, tiller in the other, working constantly to get all we could from our boats and trading the lead frequently. Where the river turned into the wind, we tacked carefully, playing the puffs for boat speed. Where a wall of trees all but shut down the breeze, the treetops continued to bow, rustle, and swish to the wind, but down on the water it was touch and go for us to maintain momentum.

Another bend and the Dover bridge came into sight at the far end of a widening expanse of the Choptank. It’s a new steel and concrete girder bridge that rises 50′ over the river. Just a few yards upriver, the old steel-truss bridge that it has replaced remains, freshly painted a bright blue, its swing span left open. We slid under the new bridge and then between the bulkheads of the old one.

After clearing the Dover Road bridges, Eric heaved-to in INDIGO to catch photos of TERRAPIN running downwind past the two spans. Overhead, the leading edge of a fast-moving storm cell approached from the southwest.

Eric was a few hundred yards ahead of me when I felt a few drops of rain on my back. Seconds later, Eric was on the radio. “Weather alert. Thunderstorm warning and risk of 35-knot winds.” This, on a day with no mention of rain in the forecast. I checked the chart. There was a 100-yard-wide cove, the entrance to Mitchell Run, just ahead on the river’s left bank. A shallow bar guards the entrance, but it was the only shelter available. I hailed Eric on the radio and told him where to look for it. “I think I see it,” he called back.

INDIGO hit the bar first, slid to a stop, but then shifted forward and worked herself free—Eric would reach shelter in time. I tried closing with the shoreline farther downstream, hoping the bar would be deeper there, but it was not.

TERRAPIN’s bilgeboards kicked up when they contacted the bottom and she stalled out. I dropped the sails, raised the boards fully into their cases, and shipped the oars. Over my shoulder, I could see a tall, thick gray mass of cloud flashing with lightning approaching from the southwest. I pulled hard on the oars. At first, there was little response, but then TERRAPIN began to edge forward. A few more strokes and I was free.

With the wind behind me, it took little time to row into the cove and get the anchor down. The water was shallow and surprisingly clear; I could see the anchor hit the bottom. We were secure close behind a line of trees and as ready as possible for the onslaught.

The thundercloud approached, boomed, cracked, and flashed. Sharp bolts of lightning broke the increasing gloom as the heavy cloud eclipsed the sun. But the storm’s track took it just south of our little haven. I breathed a sigh of relief. Not long after, to the east, the thundercloud, as white as whipped cream, was brightly illuminated by the sun descending to the west.

By 6:30 p.m. the wind had all but died. Even so, forecasts for gusty northwesterlies would persist through the night and the next day. Should the wind return, we could become pinned in Mitchell Run. Eric and I rowed back into the Choptank and found the breeze slackening and the upstream current building. We saw our chance. Steady work at the oars can push TERRAPIN at 1-1/2 knots, but with the current the GPS showed she was moving along at a steady 3 knots. It didn’t take long to cover the mile to the point where Kings Creek empties into the Choptank from a wide marsh. Next to the marsh lies Kingston Landing, another spot of solid ground, once an access to trade but now a single boat ramp. As we rowed past the marsh, dozens of swallows rose and darted across the darkening sky that was first a deep blue, then a muted purple, before all settled down for the evening. Far to the east, the storm clouds had collected in a long band. Lightning flashed erratically as the front swept off to the east, the mountain range of clouds showing its peaks behind the distant treeline.

Anchored about 50 yards apart, we settled into our evening routines. Eric brought real food, fresh goods that require actual cooking, while I took the minimalist approach–boiled water poured into a freeze-dried dinner bag or just cheese, crackers, nuts, fruit, and cookies. After eating, it was time to settle down to the forecast and charts for the next day’s progress, and then opening a book for an hour or two. The Autumn Leaves design includes an especially comfortable reading chair that folds away under the aft end of the berth flat. I settled in to read a few more chapters of Chesapeake Bay Schooners by Quentin Snediker and Ann Jensen, the best account I’ve found about the heyday of commercial sail on the Bay.

The vistas rarely disappointed up the full length of the Choptank. Here, anchored at the mouth of Kings Creek, we had a fine view across a wider stretch of the river.

Saturday morning, I checked the forecast on my cell phone. The small-craft advisory persisted, but I was hard pressed to believe it—the temperature had dropped to 67 degrees and the air was dead calm—but I was not going to shake out the reefs. I stood up in the companionway and saw INDIGO riding to her anchor, reflected in the glassy calm of the morning. Eric was busy readying for our next leg. As we got under way, the forecast began to show itself. Heavy gusts plowed in from the northwest. I looked at the chart. In these conditions, exiting the 90-degree bend at Williston might prove difficult.

By mid-afternoon, it was gusting into the upper 20s, whipping down and across the river at random angles. But the shifts had not brought the wind head-on and we made good time until we encountered the bend at Williston. Eric had been working his way up the river just ahead of me, but as the village came in sight, INDIGO did an odd shuffle into the mouth of Mill Creek, something clearly amiss. Frequent tacks in the erratic air had tangled Eric’s jibsheets on the bow cleat, and he needed to pause to sort them out.

I pressed on, hoping to find a sheltered spot to drop anchor until Eric was ready to move on. But as soon as I followed the river’s turn to the northwest, I felt the full force of the wind the small craft advisory had warned about. I was knocked back on every tack, unable to gain ground before I was across the river and forced to come about once again. Frustrated, I doused sail and dropped the anchor.

The fetch here was short, but the whitecaps were seething and the tide had begun to ebb. Progress was no longer possible. The broad palm of the claw anchor was reluctant to grab the soft, muddy bottom. I fed out more rode. TERRAPIN continued to drag backward 20′, 30′, then took hold. The bow bucked and pounded on the chop and the mizzen, left standing to keep the boat’s head straight, rattled loudly on and off as TERRAPIN swung and fought her anchor but I had a moment to catch my breath.

A hundred yards behind me, Eric had put his anchor down and decided to wait for the tide to ease. His boat came to rest just off a vacant private dock, so he eased her back and tied up alongside.

I had the anchor down after failing to advance against tide and wind at Williston, but TERRAPIN dragged her hook through the mud until she was just off the fallen tree at the right side. The Choptank narrows significantly in this bend, amplifying the effects of the 4′ tidal range.

We sat tight for several hours, watching and waiting for wind and tide to ease. The current began to slacken as the tide approached the low mark, and we were itching to get on our way. The gusting had moderated slightly as well and five turkey vultures that had been sheltering in the trees next to me took flight.

The whitecaps were almost gone altogether, and there was a well-protected anchorage at Watts Creek, about 2 miles upstream. If we could reach it, we would enjoy a peaceful night. But my situation was difficult: I was anchored close to the northeast shoreline and a treeline that periodically blanketed the wind. Halfway across this narrow stretch of the Choptank, there was no protection at all from the still frequent blasts of wind. And spreading out from the far shore lay a mudbank barely covered by the receding tide.

I hauled up the anchor, raised sail, and turned TERRAPIN’s nose across the river. First, there was a gentle nudge from the light air behind the trees. She moved forward two, three boat lengths. Then the next gust hit. She heeled hard to port and began to accelerate. But before there was way on enough to tack back, her port bilgeboard grabbed the mud on the west side of the river. She heeled hard, farther over than I’d ever experienced, then came to a dead stop, still at a sharp angle despite the boat’s flat bottom.

I frantically let the sheet go and freed the halyard from its cleat. The sail swung off to port, but in this wind, friction tied up everything and I was forced to go forward to pull the yard down to the boom, which is supported by lazyjacks. The boat leveled out some, but not until I pulled up the leeward bilge board did she straighten, her belly now flat on the muck.

I looked back down the river to see how Eric was doing. He appeared to be tied up to a bulkhead. Would I be stuck here, glued to the bottom, until the tide freed me?

I shipped my oars and, standing in the cockpit, started pulling astern. The blades locked in the mud and bent alarmingly. I eased off; I didn’t need broken oars, too. Getting back to the rowing with more care, there was some perceptible movement. Then a little more. The wind was still a solid 20 knots, the trees still hissing and swishing, leaves turned bottom-side up, and that pressure was now helping slide the boat along the bottom as I forced it away from the bank. Five minutes of work and she eased free. I raised the main. I was determined to round that bend, but two tacks later, I realized that anything gained through the water had been lost to the still-ebbing tide. Defeated, I sailed TERRAPIN back down around the bend and anchored in the partial lee of a mixed stand of thin, vine-woven trees arrayed along the northwest bank.

Eric had pushed off his dock at the same time I had raised my anchor. INDIGO, rigged as a jib-headed yawl, was promptly spun around by the unpredictable gusts. His attempts to tack proved no better than mine. As his boat was turned, he released the mizzen sheet to regain control, but it didn’t work. INDIGO took another turn, this time twisting the freed mizzen fully forward, where it jammed against the main, locking the sails together. INDIGO was out of control and driven headlong into the aging wooden bulkhead. A few neighbors wandered down the lawn behind it to say hello, unaware that this hot, breezy day was sorely testing our two little boats and their skippers, too.

As the sun dropped so did the wind. Eric was eager to move on to escape the horseshoe turn at Williston. He started rowing into the setting sun. I squinted to watch him disappear into the orange glare reflected off the river. Five minutes later he hailed me on the VHF. “Come on, it’s great!” That was all the encouragement I needed.

After an utterly still night, Sunday dawned cool and calm on Watts Creek, a welcome salve for Saturday’s blisters. This was the best-protected anchorage along the river, but at low tide our boats, even with their 8″ draft, touched the bottom on the way out.

After a second stretch at the oars through the darkening evening, we anchored in Watts Creek, satisfied that we had escaped from the bend at Williston. We rafted our boats together as the day’s last light slipped away. It was a remarkably quiet evening and felt all the more calm in contrast to the day’s relentless wind. We toasted our little success with a shot of rum.

We stirred Sunday morning before the sun was over the trees. The sky was brilliantly clear, the humidity thankfully down and, at that moment, the air light. We had anchored just 2 miles downriver from the landing in Denton and Eric was determined to row the last stretch. He got INDIGO under way first and soon disappeared around the headland at the mouth of Watts Creek.

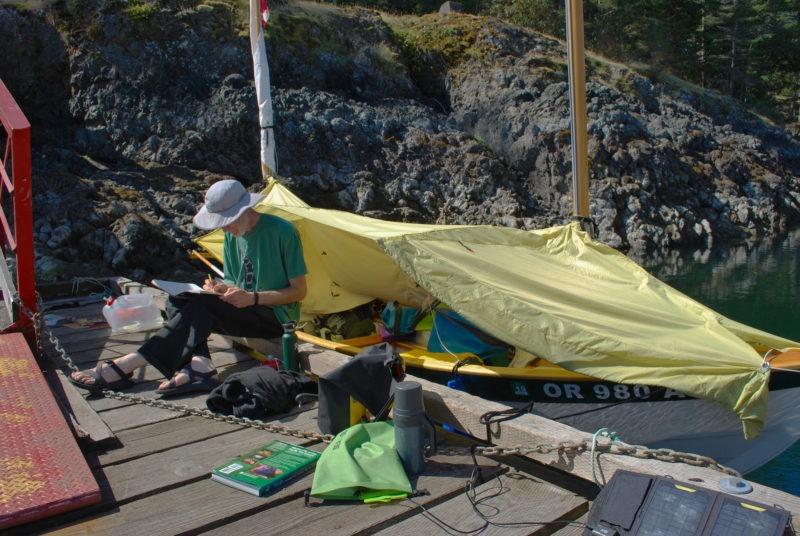

I savored the adventure, and coffee, Sunday morning in Watts Creek. Eric paddled my inflatable packraft to capture the image.

A few minutes later, I rowed out from the creek to deep water and found just enough breeze to get TERRAPIN moving. Looking upstream, I saw Eric standing between his jib and jigger, swinging the oars steadily. His progress was good and before long he disappeared, first half-obscured by the marsh grass, and then lost around a bend.

The Choptank quickly narrowed from one-third mile at the creek to 150 yards just a half mile to the north. There was a wide stretch of marshland on both sides; thick stands of jade green arrow arum along water’s edge, its broad spiked leaves pointing to the sky, a mottled mix of marsh grass behind it. Beating to windward in this narrow passage to Denton required short tacks all the way. I didn’t dare test the depth close to the exposed mud banks. I needed to maintain boat speed to guarantee the tacks. Twice, I stood to hold the boom out to windward to bring TERRAPIN’s head across. After 1-1/2 miles of this zigzag route up the river, I reached the concrete-and-steel girder bridge at Denton. I sailed to within 10 yards of the span, where the bridge and surrounding buildings killed the wind. I took to the oars to pass under the span and pulled into the wharf. Eric was standing by to grab a line.

I arrived in Denton on Sunday morning. The mural on the bridge piling is an enlargement of a photograph of Denton’s wharves in 1904, the waning days of river commerce under sail. TERRAPIN had already passed under the bridge, and Eric had rowed her against the current to edge her over to the bulkhead. TERRAPIN’s electric motor remained in its stowed position the length of the cruise, and the double reef in the mainsail was never shaken out.

As we secured our boats Mike Reese, a longtime Denton resident and retired boatbuilder, walked down to say hello and have a look at our boats. He said the Choptank has been gradually silting for hundreds of years, ever since the forests were turned to farmland, and the river, which was once deep enough for cargo-laden schooners, is now so shallow that access to the town docks is difficult. Powerboaters still come upriver because the fishing is good. I asked, “Do boats reach Denton by sail anymore?” He said we were the odd exceptions.![]()

David Dawson is a retired newspaperman who has been hooked on boats since he was a boy, when his dad built a plywood pram. He does most of his cruising on the Chesapeake Bay, but has taken a variety of trailerable boats elsewhere to explore waters from New England to Florida. Nearer to home in Pennsylvania, he enjoys kayaking the local rivers, lakes, and bays.

The Choptank River and the Underground Railroad

In the early 19th century, the Choptank River was a busy place. Schooners tied up at Denton’s wharf to take on lumber, wool, tobacco, grains, tanbark, and other cargo to be shipped to Baltimore. A constant stream of sailing vessels ran up and down the river. While the age of sail casts a romantic light on the region, it’s important to remember that the early economy of the Choptank—like the rest of the Eastern Shore—was built largely on slave labor. The cargo carried by those vessels, and even the wood used to build some of those ships, was produced by enslaved people.

During the middle of the 19th century, a network of resources for escapees, known as the Underground Railroad, developed and Caroline County became dotted with safe houses in the area surrounding the Choptank River. But outside the courthouses in Denton and Cambridge, people were bought and sold; inside, severe sentences were handed down to any who helped those who sought their freedom.

In March 1822, American abolitionist Harriet Tubman was born into slavery about 10 miles south of where we launched in Cambridge. She and two of her brothers, Henry and Ben, later worked on a plantation at Poplar Point, just upstream from the town of Choptank, adjacent to the old landing that is now the Choptank marina. On September 17, 1849, she escaped with her brothers, but she returned to the Choptank area several times to help dozens of others escape. The tracks of most of those she helped free ran parallel to the river as the escapees headed north toward Philadelphia and, in some cases, on to Canada.

Our visit to the Choptank fell on the 200th anniversary of Tubman’s birth and we reached Denton on the Juneteenth holiday commemorating the emancipation of those who had been enslaved in America.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.