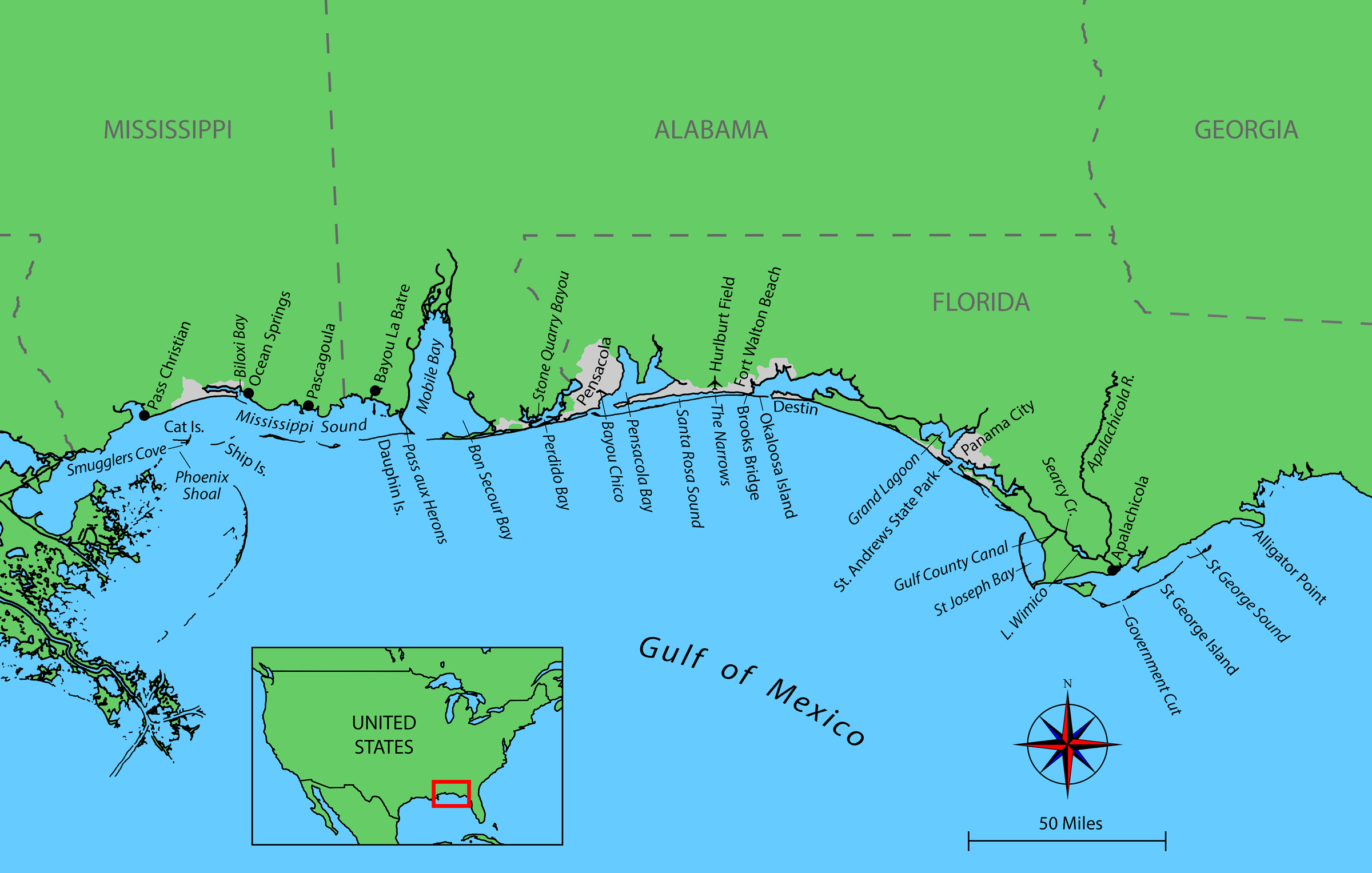

Maybe it was not meant to be. My cousin, Mark Kelly, and I were halfway through the second day of a nine-day trip from Alligator Point, Florida, to Pass Christian, Mississippi, sailing MYRNA C, my Norwalk Island Sharpie 23. On the first day, we had made only 17 nautical miles despite sailing for 10 hours. We had 310 nautical miles to go.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorI trailered MYRNA C from Pass Christian, Mississippi, to Alligator Point, Florida, one month prior to the trip to maximize the vacation time Mark and I would have for sailing. Jim Hill let me keep my boat at his dock on the canal, which is just across the street from our family’s house. We made final preparations for departure here.

On this second day, the aluminum booms of the main and mizzen clanged against their blocks as we wobbled west, several miles off of St. George Island’s shore, which was visible only as an eggshell-thin line of sand, dotted with pastel beach houses. We had strayed farther out into the Gulf of Mexico searching for stronger winds, but the wind continued to fall away to a meager 6 knots.

The sun burned through the overcast sky and radiated heat like a stove in a sauna. A long, nauseating swell rolled from the southeast. The mainsheet hung limply over the lifelines and drooped into the water. The trip was at risk of turning into nine days of motoring and Mark, an avid canoeist who had done very little sailing, began to talk up the advantages of paddling.

He and I had conceived this trip in the summer, when the winter COVID surge was a theoretical risk. Amid life in endless quarantine, it had slipped my mind until we were catching up on the phone in December after I had been vaccinated and Mark expected his shot within days. Suddenly, a trip together seemed possible.

As we sailed across Apalachicola Bay on the second day, we spread the spinnaker out on the cabintop to dry. We had tried to fly it that morning in an attempt to continue sailing offshore in order to avoid the Intracoastal Waterway, but the wind was too low and the swell too high to keep it flying

As an internal-medicine resident in Los Angeles, Mark had been working the COVID wards, and was burned out. In my general-surgery residency in New Orleans, we were spared primary responsibility for COVID patients, but we did make the tracheostomies, place feeding tubes, and insert long-term dialysis lines for the sickest patients. Mark and I needed a break from seeing the dissolution of life from the virus. Both of us needed renewal.

But what we had found so far on our much-needed vacation was frustration. Defeated by two days of light winds and sail-collapsing swells, we turned on the outboard and headed for Government Cut, a man-made 500-yard-long passage through St. George Island. As we approached, two granite-boulder jetties reached out from the low, barrier island sand to lead us from the Gulf into Apalachicola Bay. On the east side of the Cut, blocky mansions leered imperiously over the inlet. From their second-floor porches, wooden steps poured down to boardwalks that stretched across the scrubby dunes and the bay to their docks and their boats. On the west side of the Cut, the other fragment of St. George was uninhabited; palmettos, sabal palms, and sea oats held the wild dunes in place despite storm surges washing over it and the constant scouring of wind and tides.

Once we motored clear of the island, we raised the sails again, more out of obstinacy than from anticipation of pleasant sailing. There still wasn’t much wind and we crept northward, making only around 3 knots. The bay’s water was dirt-colored and the sky remained dull and gray, amplifying the malaise on board. Mark’s enthusiasm seemed to be waning, but he stayed upbeat, perhaps to counter my worries over whether he was enjoying himself.

A dredging pipeline ran along the channel from the Cut to Apalachicola, attended by barges and tugs. The grease and rust, thick ropes and cast-iron cleats contrasted with our bright blue, dainty plywood hull and white sails. As we passed one barge, we saw two workers in tattered jeans, gray T-shirts, and survivor orange life jackets sitting on spools of cable. They were hunched over, gazing into their phones, oblivious that we were passing within 50’ of them. The indifference of the workers toward us underscored my growing feeling that our whole trip was flawed and futile.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

It took us two long hours to make the 6-nautical-mile crossing of Apalachicola Bay. The town of Apalachicola, occupying the point of land where the Apalachicola River spreads into the bay, was largely hidden behind tall, tan-colored reeds. Above the reeds, silver roofs flashed between runs of rolling pine. We passed under the Highway 98 bridge and started the engine again—the river’s current was too much for the meek breeze—and motored along a sleepy, salt-aged riverfront. Shrimp boats in every color of flaking paint lined the bank, tied up to listing, sun-desiccated docks.

We stopped in town for several dozen oysters and a few beers as consolation for two windless days, then continued up the river (which is part of the Intra-Coastal Waterway) at dusk, toward St. Joseph Bay. Starlight slipping through spindly cypress on the banks guided us up the main channel. The engine banged away like a lawnmower. Two hours later, we dropped anchor for the night in Lake Wimico.

After beer and oysters at Up the Creek Raw Bar in Apalachicola, we motored up the ICW at dusk. The railroad emerges from the swamp to cross over a swing bridge, which was in the open position for boat traffic.

Warm, yellow light glowed from the cabin as we raised the centerboard and rudder, reducing our draft to a scant 12″. Mark set out the cushions on his berth to starboard of the centerboard trunk. Forward, I put sheets over my half of the V-berth, the other half occupied by our bags. We fell asleep to the sound of the centerboard occasionally shifting in the trunk; the water and wind were still.

The cabin on MYRNA C is more like a floating tent than a yacht. She is just shy of the bare necessities.

We woke in the morning to fog so dense that we would never glimpse the shore of the lake. Mark pulled out the galley kit from the port side of the centerboard trunk. We put the Coleman stove just in front of the cabin hatch and got coffee going. The main boom was tied off to a stanchion to starboard to keep the sail away from the heat rising from the stove.

I wasn’t thrilled to be in the ICW, but Mark loved seeing the swamp up close. As we motored along Searcy Creek, he spotted several bald eagles, herons, and osprey.

The water remained still—not good for sailing, but excellent for making a hash of potatoes, onions, egg, and Manchego cheese while motoring. As I cooked, Mark steered us by GPS out of Lake Wimico and then 7-1/2 meandering nautical miles in Searcy Creek, flanked by dense stands of cypress and red maple standing over an endless swamp. The remaining 5-1/2 nautical miles to St. Joseph Bay were along the ruler-straight, Gulf County Canal, a 100-yard-wide cut flanked by clear cuts, building-sized piles of sand, and a shipyard. Osprey and bald eagles winged overhead, making do with what wilderness loggers had left behind.

As we emerged from the canal, men in waders wandered the turtle grass shallows of St. Joseph Bay casting for trout. The opaque, gunmetal blue water was motionless as if turned viscous and the air was thick with humidity. We motored across the dead-calm bay to St. Joseph Peninsula, where we tied up at the state-park marina to wander the powder-white dunes, at 35′, the highest in the state. As we walked the beach, the southeast swell that had frustrated our efforts to reach this place in the Gulf pushed foam up the sloping beach in lazy, draping ribbons.

The forecast that evening called for a nor’easter to bring winds of 15 to 20 knots, and we intended to sail overnight to make the most of it. I tried to prepare Mark for what the night might bring—wind-driven spray, enough tension on the sheets to make trimming a real effort, and the likely need to reduce the amount of sails we had up to go faster. It wasn’t getting through.

The now three windless days had given him the impression that sailing was only longing for wind that never seemed to come. I was nearing the same conclusion. If this front failed to materialize, then it was likely that our vacation was headed toward a bailout far short of MYRNA C’s slip in Pass Christian—and a mess of logistics.

But as we walked, the southeast breeze strengthened slightly. The undifferentiated gray sky formed billowy cumulus over the mainland to the north. The approaching low was sucking moisture toward itself. The atmosphere was charged with impending change.

Mark stopped and asked, “Do you feel it?” I did. We hurried back to MYRNA C.

Approaching across St. Joseph Bay, a nor’easter brought the wind we had been waiting days for.

After a gentle sail north on the bay side of the peninsula, we rounded the tip of St. Joseph Peninsula and passed through the 2-nautical-mile gap into the Gulf, just as the nor’easter was nearly on us, starting to spit rain, and accelerating the southeast breeze to a robust 15 knots. The booms were eased just beyond the lee rail, which was barely above the sea rushing around its curve. Mark and I were perched on the opposite gunwale and the windward chine below us was flying several inches above the water. We were making 6.5 knots: the stem churned a steady cream of white water and the trough of our bow wave stretched aft, just shy of the stern.

About ten minutes later, the front swept in. The sabal-palm-lined coast vanished behind the rain and the wind seemed to be pulled by its ear from southeast to the north. The breeze hissed through the masts and rigging. Whitecaps crowned every wave; foam sheared off the crests and streaked across the troughs.

The lee rail was now buried under the jade sea almost continuously—not how the MYRNA C likes to be. We needed a reef, stat. Mark brought the bow into the wind and handled the sheets and halyards as I crawled onto the foredeck, the EPIRB in my zippered life-jacket pocket and trailing a long tether, to drag down the crackling mainsail. As I tied two reefs into the main, I turned back to see Mark staring at me, as if astounded that he had decided to take time off from Los Angeles’ COVID ICUs to spend his vacation with a lunatic who would undoubtedly cost him his own life. It was about 5 p.m. by the time we got the reef in.

The wind had strengthened to 20 to 25 knots with higher gusts. MYRNA C, flying only her double-reefed main, felt spry despite these conditions, a special feature of sharpies as they have no heavy keel to make their movement in heavy seas laborious. Nonetheless, Mark was finding the sea state difficult. After briefly ducking into the cabin, he emerged to complain about the smell of gasoline, and then vomited into the cockpit. He then got back on the rail, his eyes fixed ahead. The only way through this was through it.

We started making our way west again. We were about 20 nm from the inlet at Panama City and 4 nm off the coast. Everything was gray now, and then, as the sun dipped below the horizon, just black.

The wind had shifted a little more to the east and we sailed on a close reach toward Panama City, whose lights appeared then on the horizon as an apocalyptic mauve glow. The only other lights were the flashes of green and red spray dashing in front of our navigation lights and our headlamps on the sails as we watched the luff.

We reached closer to shore along St. Andrews State Park, and in its lee, we were able to raise the reefed mizzen. We made 6 knots in the calmer waters. The city’s glow outlined sabal palms growing behind the dunes and farther west, condominium towers, dark but for a few lit windows, swirled with mist. Around 9 p.m., we reached the Panama City inlet. We turned on the engine with relief for once, and motored through the choppy ¼-mile-wide pass. Three small Coast Guard boats, whose lights we had seen coming in from offshore, overtook us. I wondered if the crews were surprised we had not called them for assistance.

Grand Lagoon, Panama City’s harbor, was pitch black, and its channel-marker lights were lost in a deceitful mashup with lights on shore. Mark and I had to yell to hear each other over the din of the engine and the wind. We first tried to tie up at the state park landing. Mark stood on the bow—his sea legs seemed to be coming in—dockline in hand. As we neared the dock, I could tell he was wavering between fending off or jumping on to land. He made the leap, but came up short. I heard the splash and then silence. Just to port, I saw his headlamp shining up through the water from the muddy bottom.

Damn, I thought, all that hard sailing and Mark knocks himself out right when we get to shore. I yelled, “Mark!” And then I could just make out Mark’s silhouette. He was standing in about a foot and a half of water. Fortunately, his headlamp had fallen off his head and only it was underwater. He was soaked and shivering. He got back on board and into dry clothes. This wasn’t going to be a good place to tie up.

I looked at the chart for other options. We decided to try Bay Point Marina. Back in the black harbor with our spotlight, we noticed that some channel pilings had no sign boards. On others, the reflective tape fluttered in the wind like tell-tales. Ahead, where we expected to see the lights of the marina, there was only more darkness.

We looked again at the chart and GPS. By those accounts, we were in the middle of the marina, but in reality, we were surrounded by open water. I later learned that the marina had been destroyed a couple years prior by Hurricane Michael, and all the pilings and docks had been pulled up to start fresh.

We threw off our anchor. Mark went to sleep without dinner. I made a peanut-butter sandwich for myself, then rearranged my area of the cabin into equally disorganized arrangements, burning off adrenaline from the day until I could sleep.

We woke to gray. The water was gray. The storm-tattered condominiums to the north were gray. The clouds were gray and drizzling. The northeast wind blew, unabated. Across the harbor to the southwest, in a cluster of marinas, boats bobbed in their slips, windward lines taut. Hundreds more boats were stacked in giant dry-storage racks; hundreds of thousands of horsepower, cold and still. On board MYRNA C, swinging on her anchor, we prepared for the day.

I suggested to Mark that we could take the sheltered ICW to the town of Destin, but the crucible of the night before had not daunted him at all. We would return to the Gulf, and this time hug close to the beach to exploit the north wind without subjecting ourselves to the chop.

Amid the gray, we raised our sails, still deeply reefed from the night before, and shot east back through the Grand Lagoon. We jibed into the roiling inlet, where the outgoing tide joined the northeast wind to drive MYRNA C, running wing-on-wing, to sea. A thin slab of slate-blue clouds lay across the horizon to the south. Gray clouds stretched up overhead all the way to the northern horizon where purple clouds assembled, a bullpen of rain bands to come.

With the temperature in the 50s and the wind blowing at 20 knots, Mark, right, and I bundled up for the run from Panama City to Destin.

The Gulf was lonesome. For the 45 inlet-less nautical miles between Panama City and Destin, we were the only boat making the passage. All day, we sailed past an endless white sand beach. Perched on top of the dunes, there was an equally endless stretch of beach homes and condominium towers, packed tight like books on a library shelf. They all looked empty today, spoiling the landscape for nothing. The wind tumbling past the buildings came at us in furious gusts separated by long lulls. We eased offshore to where the wind began to run free and steady again.

We ran a beam-to-broad reach and averaged 6 knots. The sharpie shines off the wind; its flat bottom more like a surfboard than sailboat. As the wind gusted upward of 20 knots, the boat strained to crest its bow wave. When I was at the tiller, my biceps burned from fighting the weather helm. Every 30 seconds or so, balance returned as MYRNA C hurtled down the face of a wave, soaring past her hull speed. We carried on this way for about 7 hours. Our top speed for the day was 9.5 knots.

Squall after squall renewed the winds on our starboard quarter, though the blows diminished over the course of the day. By late afternoon, our full spread of white sails was back aloft, bright against the sapphire of the sea and the still gray skies.

Choctawhatchee Bay was pouring out of the inlet at Destin when we arrived at 4:30 p.m. The murk of the bay carved a sharp demarcation through the limpid water of the Gulf. Despite the ebb flowing against us, we still made 5 knots through the 300-yard-wide entrance, though we soon after needed an assist from the engine to get under the twin-span bridge where the bay funnels into inlet. We then headed west for Brooks Bridge Marina on the ICW, where we planned to tie up for the night.

As we slipped through the shallows along the sandy, pine-lined bay shore of Okaloosa Island, we looked behind us, to the east, to see that the sky had darkened beyond anything we had seen all day. Beneath the towering clouds, an army of whitecaps advanced across the bay. A chill curled into the cuffs of my jacket sleeves. Then the rain came, pouring over us like ice water. The thrill of surfing down waves all day drained out the scuppers.

Since we were running downwind, we tried to sail through the squall with full sails but even though the unstayed carbon-fiber masts flexed to dump air, it wasn’t enough to hold off an untamable weather helm. We took down the main, and carried on with mizzen for a while, and then with just the motor to reach the marina. Freezing and beaten down, we huddled in the cabin. I called a friend of mine from medical school, Robby Ashley, who lives in nearby Fort Walton Beach. He came to pick us up for laundry, pizza, and a much-needed night on shore.

Robby had to get to the hospital for work by 6:30 a.m., so we got an early start the next day. Exhausted from the previous two days of sailing in the Gulf, we decided to take the well-protected ICW for the 35 nautical miles to Pensacola.

As we motored out of the marina, there was a northerly breeze blowing across the ICW, so we raised sails immediately. The first 10 nautical miles of the ICW here are called The Narrows. On the still water, we ghosted past bright green manicured lawns at the foot of brick and stucco homes. About a third of the way through, the channel takes a quarter-mile dog leg to the north. For 20 minutes, we tacked upwind in a 70-yard-wide channel between marsh islands to round the corner. Then, tall pines obstructed the wind almost completely, and our progress slowed to 1.5 knots. We heard the morning announcements from the PA system of a nearby school as if we were in homeroom ourselves. Songbirds flittered in the trees, singing. White egrets strolled the shore, poking in the marsh for breakfast.

The calm seemed inescapable, and I suggested giving up and turning the engine on. Mark questioned my purity and, being stubborn, I took the bait and we carried on under sail. Within a few minutes, the lee rail descended, and we were on our way again. We accelerated past Hurlburt Field Air Force Base, its runway allowing a roaring breeze to run free and blow across the channel.

After days of overcast skies, the sun finally warmed us up as we sailed down breezy and protected Santa Rosa Sound from Fort Walton Beach to Pensacola Bay.

The passage slowly widened, and soon we had made it through the Narrows and into Santa Rosa Sound. Overhead, the cerulean sky was covered by a thin, patchwork of clouds that the sun burned off as the day progressed. We made a joyful 5.5 knots on crisp, blue water topped with tumbling white caps. Santa Rosa Island lay to our south, a long, electric-white bar of sand, too skinny and low for homes or trees. To our north, the mainland shoreline, mostly pine dotted with modest beach homes, arced like velvet rope along a queue before running straight west toward the rendezvous with Pensacola Bay at Deer Point. There, we turned north to work upwind for Pensacola Harbor under a spotless sky.

Gusty winds in Santa Rosa Sound demanded frequent sail trimming and repositioning of crew weight.

That evening, we anchored in Bayou Chico, a mile from downtown, sandwiched between a tugboat base, a salvage yard, a highway bridge, and the very proper and trim Pensacola Yacht Club. An acrid, oily odor wafted over our still anchorage. Amid these implements and rewards of industry, we watched an osprey perched on a mast devour a catfish, blood dripping onto the deck below.

We sailed off anchor in the morning, tailed by the tugboats trudging to the day’s work. We slipped past the yacht club and emerged into another shining blue day on Pensacola Bay. We headed south for the Gulf with 10 knots of breeze on our quarter.

We made it out of the Pensacola Bay’s inlet—the 2/3-mile gap between Santa Rosa and Perdido Key’s slender eastern peninsula—and sailed into the emerald Gulf, and crossed over a shallow, sandy bar on the west side. The water was so clear we could see individual grains of sand on the bottom 3′ below us. But the wind soon died completely and our speed dropped below one knot. Unfortunately, we had to motor.

Needing a break from the engine on our way from Pensacola to Stone Quarry Bayou, we anchored in the emerald waters offshore of the Flora-Bama Bar and waded ashore to see what the fuss was about.

A few hours later, exhausted by the noise, vibration, and monotony of the engine, we anchored just off the beach from Flora-Bama Bar, a notorious live music venue situated on the Florida–Alabama state line. We waded ashore in waist-deep water, holding our dry clothes, wallets, and towels above our heads. On this cool day in early March, about three dozen snow birds (northerners who spend the winter in Florida) were playing Bingo in an outdoor covered area. The crowd was a far cry from the raucous spring breakers I had associated with the place.

Upstairs in a dim, neon-lit lounge, two gray-haired men strummed covers of songs by Merle Haggard, John Prine, and Hank Williams. We sipped cheap draft beer and downed a few dozen oysters. The wind strengthened in the afternoon, but it was from the west, useless to us: MYRNA C does not excel upwind. We stayed for another couple of sets. In the late afternoon, we motored 10 more nautical miles into Perdido Bay. Just before dark, we dropped anchor in tiny Stone Quarry Bayou, a 1,000′-long by 200′-wide pine- and cypress-lined cove.

After anchoring next to a shipyard in Pensacola, waking up to pine and cypress in Stone Quarry Bayou was a welcome change of scenery.

We woke up pre-dawn to get motoring through the ICW out of the way. As we prepared to leave, a fiery sunrise traced delicate pine trunks as they rose to filigreed crowns. By 8 a.m., we were done with the engine and had entered Bon Secour Bay, in the southeast corner of Mobile Bay.

We weren’t thrilled to be motoring after leaving Stone Quarry Bayou, but the still water at sunrise made up for the racket of the outboard.

With a steady 10-knot east wind, we pushed west, wing on wing, at 4 to 5 knots. For a couple of miles, we were shadowed by a lone man in a beat-up center-console tending his crab traps. His line of white buoys ran along the channel like a string of pearls. His black Lab stood in the bow, barking at the pelicans that swarmed the boat at each trap.

We crossed the vast lower end of Mobile Bay sailing wing-on-wing. For much of the way over, we puzzled whether the oil platforms there were still active.

We sailed steadily across the vast Mobile Bay, some 20 nautical miles. Old oil platforms dotted the horizon. A rust-coated small tanker with a Greek flag slogged up the bay—we had passed from Florida’s tourist beaches to the industrial coasts of Alabama and Mississippi.

On the west side of the bay, we slid under the Dauphin Island bridge in the Pass aux Herons with a 12-knot breeze at our back. We had entered Mississippi Sound, my home waters, after six days of sailing. I went below for a nap. My ear was pressed against the plywood hull and I heard chirping under water. I came back up on deck to find Mark, who was born in Wisconsin, grinning as a pod of a dozen dolphins swam alongside us. They stuck with us for two hours, Mark’s entire shift at the helm.

We used paper charts for navigation, and the handheld GPS to keep track of our top speeds. Here, Peter measured the distance across Mobile Bay.

With the exception of Dauphin Island to the east, the barrier islands in the Sound are National Seashore and so have remained undeveloped. Though not protected, the mainland from Mobile Bay to Pascagoula is lowlands and marsh with only scattered, small settlements. While the area appears pure and untouched, squiggly purple lines on the chart indicate pipelines running between the islands, rushing oil from offshore platforms north to refineries in Pascagoula.

Once well into the Sound, we headed northwest to the marshes between Pascagoula and the town of Bayou La Batre, which, from what we could tell from the binoculars, is home to a large shrimping fleet and a casino. We anchored in an old channel near a sandy, pine-lined road that ended in the ruins of a wharf. With the gray sky, pale marsh grass and sunless sunset, the place felt haunted. We imagined it was once the coastal access for an antebellum plantation.

Mark’s birthday brought strong winds and this sunrise as we hit the trip speed record, 10.7 knots, heading from the marshes near Bayou La Batre to Ocean Springs just after dawn.

We woke at 3:30 a.m. the next day to take advantage of the forecast strong northeast breeze to sail to Ocean Springs and then carry on to Cat Island.

We sailed off anchor in the dark, the sky faintly lit by the hellish glow of Pascagoula’s refineries, and headed south to stay clear of the shallows along the mainland. As we moved deeper into the Sound, the wind, uninhibited by the trees, gathered strength. Soon we were steaming along with full sails, wing-on-wing, in 20 knots of breeze, pushing an average of close to 8 knots.

At the first rays of morning light, we turned up to a broad reach. The weather helm became irrepressible. Mark, who was a sailing novice just a week ago, suggested a reef. I agreed that we were close to that, but I wanted to try to adjust the sails first. I eased the mainsail and immediately, a great burden was released from the boat. Perfectly balanced, with pressure on the tiller no more than if we were sailing at 4 knots, we accelerated to an exhilarating 10.7 knots. For 30 minutes, we careened down wave after wave on 10-knot runs until rising winds and shoals forced us into a heading further upwind that required reefing the sails.

We carried on past a tangle of navigation aids outside Pascagoula’s refineries and on to Biloxi Bay, which led us into Ocean Springs. The town sits on rolling hills that run right down to the water, a unique topographic feature in these coastal plains. Giant live-oak trees spread their canopies over streets and homes. The downtown is vibrant with restaurants and shops, though the pandemic seems to have taken its toll: the family-run deli I had eaten at the last time I was here was now shuttered. We had greasy egg-and-cheese bagel sandwiches at Lil’ Market and visited the art museum to see Walter Anderson’s watercolors of Horn Island, which he visited by rowing an unseaworthy skiff 6 nautical miles from the mainland.

It was by then early afternoon, and we needed to set sail to make the 12-nautical-mile open-water crossing to Cat Island, by nightfall. We cruised Biloxi Harbor, past its crowd of casinos on wharfs over the water—Harrah’s, Golden Nugget, Hard Rock, and Beau Rivage—before turning into the Sound. A 12-knot north wind carried us at 5 to 6 knots.

Smugglers Cove on Cat Island was our last and best anchorage.

Cat Island is T-shaped and, oddly for a barrier island, its beach runs north–south, which is perpendicular to nearby Ship Island and every other barrier island on the north Gulf coast. Midway along the beach, a 4-mile extension of high ground runs east–west with dense pine and live oak forest anchoring its spine.

We made it to Phoenix Shoal at the southern tip of the beach at 5 PM. We crossed the 2′-deep bar with the centerboard up and the boat heeled way over, taking advantage of our shoal draft to cut miles from the end of the passage. We settled up against the beach in Smugglers Cove as the sun fell below a cloudless horizon.

In the last year, because of the isolation imposed by the pandemic, I’ve spent some 10 nights anchored at Cat Island. Of all the barrier islands in Mississippi Sound, it is the only island where development, save a couple radio towers peeking above the tree line, is invisible. The only sounds come from the wind, waves, and birds. It is my place of total peace.

Mark understands the appeal. We kedged close to the beach and went for a short walk in the twilight before returning to the boat. It was our last night—and Mark’s birthday. We celebrated by adding a can of chickpeas and tuna to the mac and cheese.

The beach at Cat Island is expansive and silent.

The next morning, we didn’t rush to return to land. Mark was due to return to the ICU in Los Angeles, and I was headed to Houma, Louisiana, in the bayou, for two months on a rural surgery rotation. We woke at daybreak and went for another walk. The tide was way out, and the beach stretched wide like a desert, with sand so white it looked like snow. Trash cans swept from the mainland in the spate of hurricanes last fall, were half-buried in the beach. A large, rusting tank leaned against the dunes, the sea air doing its best to dispose of it. We crossed over the shoulder-height dunes to a sandy road crowded by forest that took us into the interior. Within minutes Mark spotted two birds on his bucket list: an American kestrel and a Mississippi kite.

The interior of Cat Island teems with birds soaring over marsh creeks lined with pine and oak.

Shortly after, we reluctantly hoisted our sails and eased away from our anchorage, headed 10 nautical miles northeast, home to Pass Christian, Mississippi. Despite nine days of constant motion and hard sailing, neither of us was exhausted. We had been renewed.![]()

Peter Sawyer is a general surgery resident in New Orleans, Louisiana. He learned to sail when he was 11 years old at Camp Sea Gull, a seafaring summer camp on the North Carolina coast. He has been at it ever since.

The author wishes to thank his parents, Paul and Jonette Sawyer, for providing a home base for this trip at their home in Alligator Point, Florida, and for asking questions that needed to be asked. He apologizes to his mom for making her worry and to his dad for having to hear about it. He also thanks their neighbor, Jim Hill, who let him keep MYRNA C at his dock for a month prior to the trip.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

What a great story. Thanks for this well-written and well-documented (by very good photos) account of a journey I have wanted to make over familiar waters. All the challenges are recorded, and yet a reader may find that the account of the journey will evoke a desire to follow the same path. Thanks again!

Awesome adventure story. Good suffering was done, great memories had. Love your sharpie.

Cheers, Bob

Never sailed in those waters nor ever likely to, so it is a treat to read about this cruise there. Thanks!

I have made that trip the other direction. It was fun to recognize all the landmarks that you mentioned. That was 30 years ago and things were not quite as developed, but it still felt familiar. I used to fish in Apalachicola, scallop in St. Joe Bay, and surf on Little Saint George Island. We would paddle across the Government Cut and once, when the current was strong, another guy I knew was swept out to sea on his board and had to cling to a buoy until a shrimp boat picked him up. I sailed through a squall near Panama City that was truly savage. Gulf Shores used to be great, but has turned into a condominium-laden racket. Dad used to camp on Cat Island as a kid and I still get out to Horn Island occasionally.

Thanks for the memories!

Nick

Spent all my youth on those barrier Islands. What wonderful memories. Gulfport was my hometown.

Reminds me of the old sailor’s adage, “Hell is paved with glassy ground swells.” Hard on rigging, the boat, and the crew.

Great story. My sailing (and kayaking, in the last few decades) has been in the Puget Sound area, and points north. Very different kind of country, but certain areas of the sound are highly developed with industry, condos, and private residences, while others still remain more or less wild. Although a sharpie would be at home in some areas, deep draft vessels are the norm with an abundance of deeper waters.

As for weather helm, I would rather have a bit of it. I find a neutral helm frustrating, as you can’t feel what the boat is doing, or wants to do, but have to be constantly vigilant, eye fixed on the sails to avoid luffing, or what’s more difficult to discern (especially for a novice), stalling the sails by sailing too far off the wind.

At Chico Bayou in Pensacola Bay you anchored at my marina – Yacht Harbor Marina.