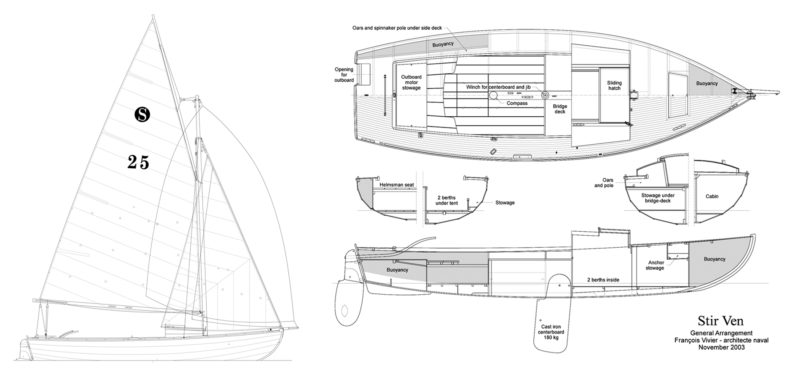

With his Stir Ven design, a 22′ LOA centerboarder, François Vivier took first place in the “neo-traditional” category of a 1997 design competition organized by the French magazine Le Chasse-Marée. His main design objective was to balance the aesthetics and appeal of a purely traditional sailboat with a modern hull’s efficiency of construction, maintenance, and overall performance. Nine years and twenty-five boats later, it seems that he has fully reached his initial aim.

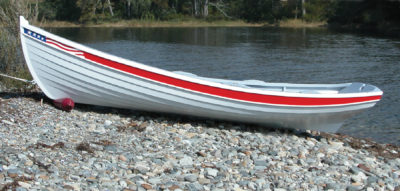

Designed at first with amateur builders in mind, Stir Ven has been refined several times, and the design is now being built professionally by the north Brittany boatyard Grand Largue, which produces versions ranging from a do-it-yourself kit to a fully equipped, ready-to-sail boat. Vivier’s very detailed drawings and instructions do not mean that Stir Ven’s lapstrake plywood-and-epoxy hull is an easy one to build, especially for beginners. Previous experience with a smaller lapstrake project—a Tom Hill design could be a nice training project—is more than recommended.

Photo by François Vivier

Photo by François VivierUnder a single reef, a boat built to François Vivier’s Stir Ven design bravely beats to windward in a good breeze of the type that usually prevails during the Rencontres du Morbihan, a yearly meeting of traditional boats in south Brittany, France.

The Stir Ven hull is 22′ long, 7′ 3″ wide, and has a 397-lb cast-iron centerboard. Her lapstrake planking is 3⁄8″-thick marine plywood, with 5⁄8″ bulkheads. The main structural elements, including the deck, floors, watertight compartments, and frames, are all constructed of 3⁄8″ plywood. Her cockpit sole, rudder, and rear hatch are slightly thicker, using 10mm plywood (about 7⁄16″) that is easily found in France but may be less standard elsewhere. The backbone is made of the hardwood sapele, with wood-epoxy technology used all over, fillet joints included. Long common in America, such composite construction techniques are making some inroads among the traditional wooden boat builders in France, where even today a majority favors mechanical fastenings and cotton caulking. In old countries, things change perhaps more slowly than they might….

The Stir Ven sail plan shows a powerful, gaff-rigged mainsail of 204 sq ft. Two halyards easily hoist the high-peaked gaff, which sets nearly vertical. Her 75-sq-ft genoa gives her an efficient total of 279 sq ft of sail area. For working downwind, an optional asymmetrical spinnaker can be fitted to the end of a small—but not very aesthetically pleasing—bowsprit.

Photo by François Vivier

Photo by François VivierThe boat is intended more for sailing than for rowing, but two healthy guys, each with a long oar, can maneuver in harbors or protected waters. A transom-mounted outboard, which stows in a cockpit locker, can take over when they’ve had enough.

Once launched, Stir Ven is quickly and easily rigged. When trailering, the mast, which is both light and short, lies flat on deck, resting in the tabernacle with the shrouds and forestay lashed down. Once the mast heel is fitted in the tabernacle, the mast can be hoisted by one crew member hauling on the forestay, which attaches to the stemhead fitting. After the shrouds and forestay have been tensioned properly, the sails have been hanked on, and the rudder has been shipped, you are ready to go. The tiller swings under the afterdeck, leaving plenty of free space on deck for the mainsheet tackle and the horse traveler. It’s difficult to imagine a simpler operation. Two people can get the boat from trailer to sailing in less than half an hour. Before setting sail, however, you have to remember to lower the heavy centerboard.

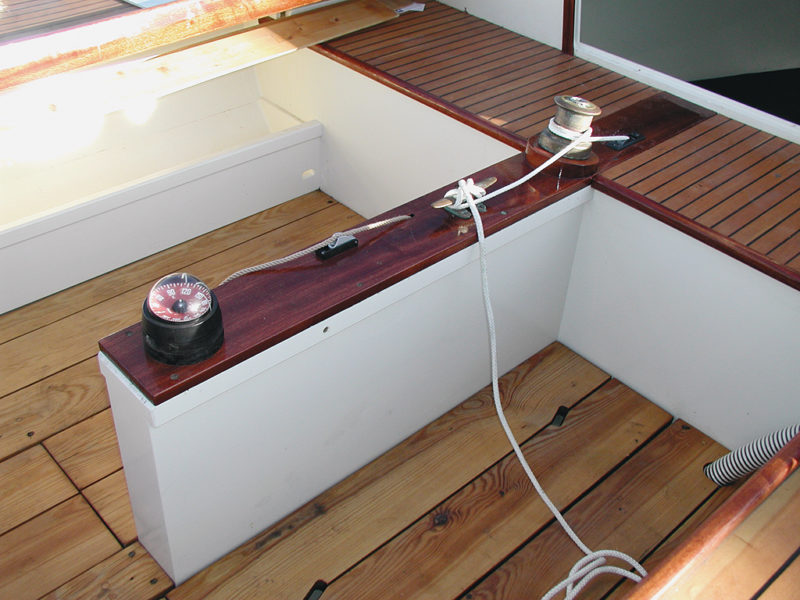

Photo by François Vivier

Photo by François VivierAn amidships winch is needed to raise and lower the 397-lb centerboard.

After her initial heel, Stir Ven stays firmly on her bilges and holds a perfect trim until the wind reaches about 12 knots. If the wind is heavier, the huge main has to be reefed to keep the helm in balance, but even at high angles of heel the centerboard is heavy enough to keep the boat steady in the gusts. For ultimate security, Vivier has designed enough buoyancy in enclosed compartments forward and on both sides of the cockpit to make Stir Ven unsinkable. Some real-world testing has since demonstrated the efficiency of the design. Her tiller is always light and responsive, without any tendency toward weather helm.

To a purist’s eye, the optional spinnaker may seem to be an incongruity in conjunction with a gaff rig, but it greatly improves downwind performance and is small enough to be easily mastered, even in a good breeze.

Stir Ven’s rig is set up in a way very similar to a big dinghy, and deck hardware has been kept to a minimum for simple handling. It will not scare newcomers. For the construction, however, parts such as the stemhead fitting, the mast tabernacle, and the main horse traveler may have to be professionally manufactured in bronze or galvanized steel. The small traveler adds a traditional touch on the after deck and improves the set of the mainsail. The main and jib halyards are made off to cleats mounted on the tabernacle, but it is also possible to lead them through turning blocks to cam cleats mounted on the cabin roof on each side of the companionway, so that all of the lines will be within easy reach of the cockpit.

Photo by François Vivier

Photo by François VivierThe Stir Ven cockpit is designed for two people to sleep on the sole, and a huge cockpit tent with full headroom can make the design into a comfortable camp-cruiser.

The small, cambered cuddy cabin is very low and does not protrude too much above the sheerline. The cabin is big enough to accommodate two usable bunks but lacks locker space. An optional cockpit tent erected on hoops greatly adds to the crew’s comfort when camp-cruising, providing a sheltered living area with full 6′ standing headroom in the cockpit. At night, two berths can be made up on the cockpit sole. The cockpit is not self-bailing, however, so any water remaining from the day’s sail will have to be pumped out. The cockpit’s size and depth, on the other hand, help children and beginning sailors feel immediately at ease and protect them from spray.

All heavy gear—water cans, fenders, and so on—find their natural place in compartments under the cockpit gratings, but they are not protected from water. The mooring line and anchor can be conveniently stowed in a forward locker, closed by a flush-mounted hatch. A bigger box just aft of the rode locker can be used to store the outboard motor, together with its portable gas tank. Because they contain heavy gear, those two lockers have been judiciously located far from the ends of the boat. Another detail betrays Vivier’s care in design: rather than using a conventional—and ugly—outboard motor bracket, he has provided a simple and stylish transom cutout for the motor, which can be removed and stored in the locker when not in use.

Photo by François Vivier

Photo by François VivierSome fittings, notably the bronze stemhead casting and the fairlead for the anchor rode, may have to be professionally made.

“I have been sailing since my childhood in the ’60s, a time when boats were mainly built of wood, designed by a naval architect, and built by experienced craftsmen,” Vivier says. “My passion for boats comes from that era, now considered as prehistoric. Since then, I have been studying ship engineering and architecture, and worked a long time for the biggest French shipyards and maritime transportation companies of the Atlantic west coast. My career ended as IRCN director (Institut de Recherches en Construction Navales— the Research Institute for Ship Building) where I have gained through experience a deep technical and practical knowledge of all types of boats, for leisure, fishing, commercial, or military uses. But for 25 years, my ‘secret garden’ has always been traditional boating, sail-and-oar, and amateur small-boat building. This led me to design for my pleasure various sailing or rowing boats, all inspired by tradition, but easy to build with simple tools at home. In 1981, I was one of the founders of Le Chasse-Marée, a yachting magazine that right from its first issue was promoting a new sailing philosophy, summed up in a simple slogan: ‘Naviguez autrement,’ which translates as ‘sail in a different way.’

“Soon after Le Chasse-Marée’s founding, I designed l’Aven, the first French sail-and-oar stock design, 80 of which have since left the yard in Loctudy. In 1985, I drew l’Aber with home-builders in mind and developed a large range of various sailing and rowing small boats. Today, the now affordable CNC technology (computer numerically controlled cutting) and yacht design software are the best tools to develop new building kits. Their high level of precision greatly simplifies and shortens a lot of usually painful and boring boatbuilding tasks, and in order to answer to an increasing international demand, I am now translating my building instructions notebooks in English—but the measurement system is still metric.”

With a jib, a genoa, a high-peaked gaff mainsail, and an optional asymmetrical spinnaker tacked down to a stub bowsprit, Stir Ven offers the sailor lots of variations. The jib sheet reeves through a fairlead to a cam cleat, but the design indicates that once the centerboard is lowered, the amidships winch can be freed to trim the jib.

This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2007 and appears here as archival material. Plans for the Stir Ven 22 are available from Vivier Boats.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

This article was a trip down memory lane for me. I read the original article in the print volume of Small Boats 2007 and mentally filed this design away as a candidate for a build project. I kept coming back to it after exploring other designs and in the end decided it ticked enough boxes to make it the one.

I started my build early in 2009, it took me 2.5 years working part time to complete the build and launch the boat in August of 2011. Ten years on I still have my Stir Ven and sail her regularly. In that time, I’ve happily rowed and sailed in no wind as well as being caught in storms over 30+ knots with just the jib up and maybe a little white knuckled! For good measure I’ve even had the whole boat fall off the trailer in the middle of a busy intersection somehow unscathed – but that’s another story 🙂

I keep the boat stored under cover in my driveway, it has required minimal maintenance over the years and the only upgrades I’ve made is to incorporate roller reefing for the jib (luxury) and lazy jacks for the main.

Its a great uncomplicated boat to own and sail, maybe one day I’ll get something bigger and capable of crossing oceans, but I think I’ll always keep my Stir Ven.

Thanks, Small Boat Magazine. If it wasn’t for your original article I’d probably be sailing something completely different!

Mike

Skipper and builder of the Vikki Bee Stir Ven 35

Far and away the prettiest boat in that size, to my eye!