Robert W. Stephens

Robert W. StephensDoug Hylan’s Point Comfort 18 offers the seaworthiness and lineage of a Chesapeake deadrise skiff, with the light weight and ease of construction a plywood hull provides.

One of the enduring pleasures of traditional wooden boats is how each boat conveys a sense of place. Every region has its distinct type, evolved to best suit that locale’s topography, weather, water conditions, and the use to which the boat is put. Available building materials can play a large role in shaping the boat, as can the need for economy in construction and in use. The interaction of cultures often has a powerful effect, as indigenous peoples pass on their building techniques to a newly arrived group who come with their own technologies. By studying the shape and construction of a traditional boat, we can peer back through the years for a snapshot of what the world was like for those who developed the type, and by looking at the evolution of the style we can follow broader trends in society. Who knew wooden boats were a solid form of anthropology?

Doug Hylan has given us plenty to study with his Point Comfort 18. At first glance, we see a simple, basic skiff—prettier than most, but a plain open skiff, nonetheless. But as we begin to take stock, we realize she is a modern distillation of the fine qualities of a Chesapeake deadrise skiff, one of the most distinctive of traditional American workboat types. Developed to take advantage of local materials and to handle the particular challenges of the shallow waters of Chesapeake Bay, the deadrise skiff is seen in all sizes up to the sail-powered skipjack sloops, as large as some 60′ overall and still dragging for oysters today (see WoodenBoat No. 233).

The watermen of the bay have long respected the deadrise skiff for its ability to keep them safe and comfortable on the changeable waters where they ply their trade. Located between the tropics and the north, the Middle Atlantic states are subject to fast swings in weather conditions. Thunderstorms and tornadoes can spring up with little warning, and strong northers can sweep across the bay, bringing Arctic cold and steep seas. Shallow harbors, creeks, and swamps demand boats of equally skinny draft, but the wider expanses can kick up to a short dangerous chop in no time. Simple construction has always been valued to reduce the investment of time and money in building these essential tools of the Chesapeake watermen, but seaworthiness is the first concern.

Robert W. Stephens

Robert W. StephensHylan built ample storage into this design yet kept her interior uncluttered. The design has storage compartments in the bow, stern, and inside the ’midship thwart.

The deadrise skiff provides both seaworthiness and value. Its unique construction springs from local materials and local culture. Where a dead-flat bottom was acceptable in the oyster fleet to the north—the large and impressive sharpies of Long Island Sound—even greater economy of construction was permissible, but in the more challenging Chesapeake, a softer ride was required. The bow, instead of being flat like a cross-planked skiff or sharpie, incorporates a distinctive and effective twisting vee, the “deadrise” for which the type is named. In early boats, heavy timbers were used for keel and chine log—most likely hold-overs from the earliest types of bay working craft, dugout log canoes, made from single trees. As boats became bigger, these hulls were made from multiple logs pegged together—techniques adopted from the Native American peoples of the bay’s shores. To form the shapely bow sections, thick timbers were fitted between keel and chine and hewn to shape, as the twist was too severe to allow solid timber to be forced to conform. From amidships to stern, planks were arrayed in herringbone fashion to allow a continuously changing deadrise angle through the midsection and the run.

The great advantages of the traditional deadrise skiff and her larger cousins are seaworthiness, simplicity of construction, and economy of operation. The early boats sailed or rowed easily, and later on, powered boats showed good speed with small engines. But, for today’s recreational watermen, the boats come with some downsides, too: weight and maintenance.

Robert W. Stephens

Robert W. StephensThe Point Comfort is an economical boat to operate. With a 10-hp to 25-hp outboard, she’ll do 12 to

20 knots.

With their thick, hewn bottoms and massive timbers, traditional skiffs would be a challenge to consider trailering. To make things worse, they rely, like most traditionally planked boats, on staying “soaked up” to remain tight. Life on a trailer would be travail for a classic deadrise skiff, and even the smallest would be a big grunt for most family vehicles. Good news for us, though—as with many traditional craft, modern materials and clever designers have permitted us to enjoy the virtues of these remarkable boats without suffering the downsides.

Doug Hylan’s interpretation features the simple and elegant shape in a finer, lighter-weight version. One of the challenges with reinterpreting traditional designs is how to remove the displacement required by heavier construction without changing the handling characteristics of the boat. Hylan has made the whole boat a bit more svelte than might be seen tonging for oysters: with a beam of 5’5″, she’s slim, and the hull depth is less than an old working boat might have—6″ instead of, say, 10″. Total hull weight is a featherweight 350 lbs, making towing behind even a compact car a possibility. But the look and the ride is pure Chesapeake.

Robert W. Stephens

Robert W. StephensThe Point Comfort’s light weight and efficient underbody make her a joy to drive. She rises to a plane smoothly without jerking.

Hylan has shifted from solid lumber to thin, stable plywood for the hull planking—high-quality, easily attainable, and dimensionally stable on a trailer. He’s been able to employ full sheets of 1⁄2″ ply for the topsides panels and the aft half of the bottom, but in the shapely forefoot the compound curvature (twist) is too great for sheet plywood, no matter how thin. Hylan solves this problem by adopting the traditional method: he employs narrow strips of 1⁄4″ plywood, laid approximately perpendicular to the keel (as would be the solid, hewn planks), and uses two layers, with seams staggered. The “planks” can get progressively wider as you move aft and the twist reduces, until amidships the thinner skins fit to the 1⁄2″ sheet in a ship-lap rabbet. The result is authentically shapely and equally effective as the original in softening a tough chop.

With her light weight and efficient bottom shape, the Point Comfort 18 is a delight to drive. We tested Hylan’s prototype with a new 15-hp four-stroke outboard with tiller steering. Hylan pointed out the only trick about the boat: a great ride is dependent on getting her to trim just right. To reap the benefits of the fine forefoot, she wants to run with the knuckle of the stem just kissing the water. Tuning by adjusting motor tilt and perhaps positioning passengers carefully is well rewarded. Hylan had clearly done his homework: with my 15-year-old son Matthew alone in the boat, the prototype looked perfect. At idle, she slid along effortlessly, cutting cleanly through the water and leaving an invisible wake. As Matt twisted the throttle, she slid ever faster along, rising bodily but never sticking her bow up. The transition to a full plane was seamless. Hylan reports speeds of about 18 knots with this power—and I would not want to go any faster than that in a tiller-steered boat. Her long, straight keel gives her the feeling of being on rails—until you turn, when she feels like the rails continue through the turn. She inspires complete confidence.

Robert W. Stephens

Robert W. StephensThe aft compartment is large enough to hold the fuel tank, a battery, and a bilge pump.

Her arrangement is simplicity itself. Our prototype featured the standard layout: a small foredeck covers a cuddy, providing spray protection and a dry place to store essentials. A platform inside the cuddy at chine level covers a flotation compartment; with additional compartments specified aft, Hylan calculates she’ll comply with USCG flotation and stability requirements. Amidships is a thwart with bulkheads creating more covered storage (a spare fuel tank and extra life jackets resided there during our test) as well as necessary structural elements. Another bulkhead forms a “mechanical area” aft, where the active fuel tank, a battery, and bilge pump were concealed in our boat. A small but ample self-bailing well around the motor adds safety and structural stiffness to the transom. The inside of the hull is smooth and uncluttered by frames or other structure. She is easy to move around aboard, and will be easy to keep clean and well maintained.

An alternative arrangement eliminates the central thwart and bulkheads, trading them for long seat boxes each side of the boat. I think I’d favor that arrangement—more options for seating and tremendous structural stiffness, if less traditional in appearance. Perhaps that’s the reason Hylan reports the thwart version is more popular by far.

Hylan also shows a center-console version that would shift the weight of the skipper out of the stern—but it’s an encumbrance in the middle of the boat, and she seems a bit too small to my mind for standing at a console.

Plans for the Point Comfort 18 are thorough and simple. Eight sheets show lines, construction plans for both versions, a construction jig setup, layouts for the topsides planks, and full-sized frame patterns. A thorough specification spells out materials and offers useful tips and hints. Hylan offers good advice couched in encouraging language. A CD includes an electronic version of the specification as well as photos of the construction and more helpful hints on scarfing and supplies.

For quick and simple building, easy trailering, a ride that’s kind to the kidneys and easy on fuel, and as a way to get your daughter out fishing or your family to that picnic spot on a distant island, it’s hard to find fault with the Point Comfort 18. And with her knockout good looks and traditional heritage, she is a true deadrise skiff for today’s water men and women.

Plans, kits, and new boats are available from Hylan & Brown Boatbuilders in Brooklin, ME. Hylan has a link on his website to many pictures of the prototype boat under construction.

D.N. Hylan and Associates

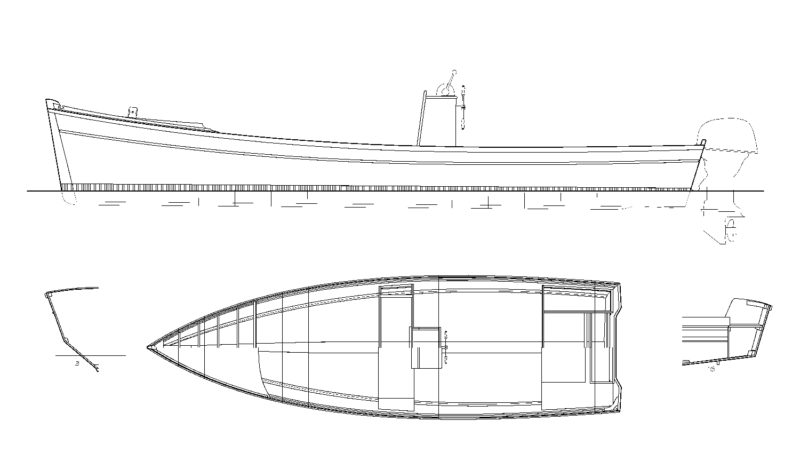

D.N. Hylan and AssociatesThe underwater sections are nearly vertical at the stem and twist as they move aft to become nearly flat at the transom. This results in a seaworthy but shallow-draft hull that can cut through a chop without pounding.

Particulars:

LOA 18′ 3″

LWL 17′ 4″

Beam 5′ 5″

Draft 6″

Weight without motor 350 lbs

Propulsion 10-hp to 25-hp outboard

Speed 12–20 knots

Great looking boat. Is that a short shaft (15”) or long shaft (20”) outboard please?