Jay Fleming

Jay FlemingLow-powered, double-ended launches called snekker are ubiquitous along the coast of Norway, but rather exotic in New Hampshire, where Andrew Wallace’s Traditional Boatworks builds these boats.

The soul of the Viking ship lives on, and on, and on, proof that it’s worth sticking with a winning formula. The graceful indigenous lapstrake craft of Scandinavia have metamorphosed into a variety of shapes and types, but the strong sheer, pointed bow and stern, and lapped planks of the boats that raided and traded throughout Europe persist, a thousand years on.

Boatbuilder Andrew Wallace can claim real Norse genes. His mother was born in Oslo and he spent childhood summers at the family’s place in Grimstad, on Norway’s southeastern Baltic coast. Unsure how to contain the boy’s energy, his mother placed him in the care of an elderly local fisherman. Man and boy headed out into the island-dotted strait called the Skagerrak every morning, no matter what the weather. There’d be a breakfast of sardines and jam on bread, then a day of longline fishing for mackerel or cod. They would land cod as large as the eight-year-old Andrew. As the years passed he was trusted with more and more of the fishing and boat handling.

The boat whose Nordic DNA soaked into the impressionable young Andrew Wallace was called a snekke (SNEK-uh). The word translates more or less as “skiff,” but in Norway it means a boat that looks exactly like the replicas Wallace is now turning out under his shingle, Traditional Boatworks, in Canaan, New Hampshire. These sturdy, burdensome descendants of Viking ships are ubiquitous in Norway. On one Norwegian brokerage site I found 934 snekkes for sale. Harbors there are crammed with them.

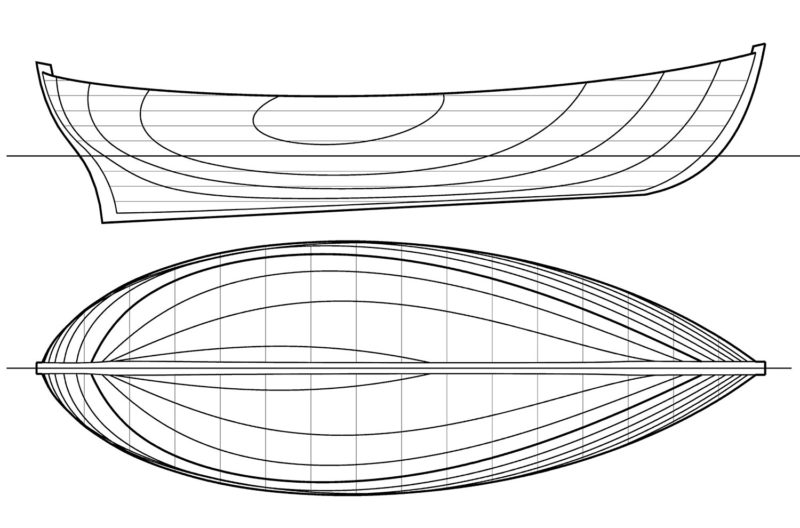

Snekker (to use the Norwegian plural) come in a fairly narrow range of shapes and sizes. Most hover around 24′ long and are either completely open like a motor launch, or have decking forward with artfully proportioned windshields, or an enclosed cuddy cabin. Wallace designed his snekke based on photos and his youthful recollections, synthesizing the best features of the type. Tim Estabrook of Yarmouth, Maine, did the naval architecture chores, including hydrostatics and Mylar patterns for the frames. The boats are built at Wallace’s shop. He’s built three so far, including one on spec, whose moorings we slipped for a test drive one unseasonably cool Chesapeake afternoon in August.

Jay Fleming

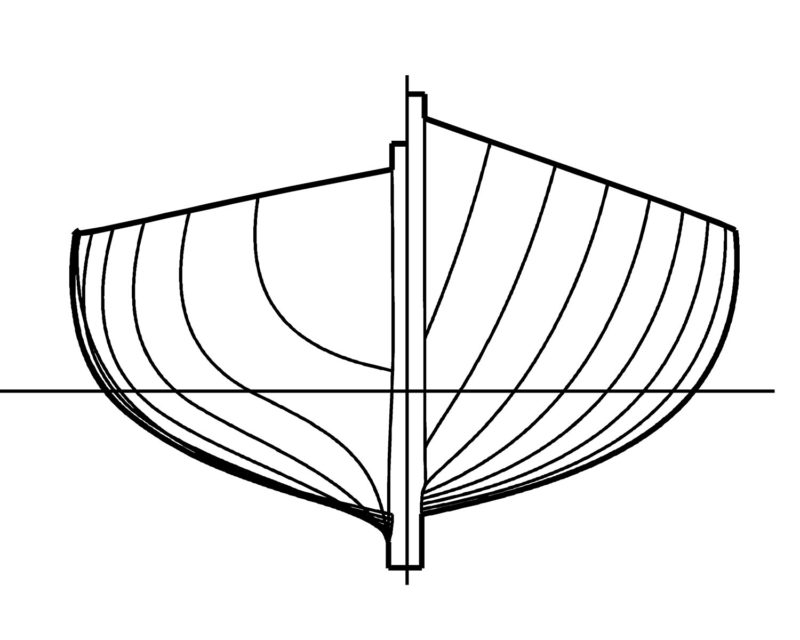

Jay FlemingThe Snekke’s outboard rudder is a trait inherited from its sailing forebaers.

This is a very unusual powerboat. It’s not just the elegant lines and all-bright finish, though to be sure we looked like a swan amongst pigeons as we threaded out of a marina thick with fashionable plastic motor cruisers. That was my first impression of the snekke: To contemporary tastes it is an unfashionable boat. It is unabashedly wooden, heavy, and slow.

Whereas an all-varnished finish can be flashy and showy, it just looks right on this Nordic workboat. Planking is 7⁄8″ European larch fastened to fence-post-like double-sawn white oak frames, 3″ square and spaced just 21″ apart. The keel is a massive 5″×9″ balk of oak. This is not a boatbuilding project for the amateur crowd—Wallace is classically trained in the art. With a hull that combines hollow garboards, tumblehome amidships, full ends above the waterline, and fine lines below, every single one of the nine planks per side requires steam- bending. The laps are fastened with wood screws and bedded in a modern polyurethane adhesive. (Wallace is ambivalent about the latter, seeing little real improvement over older nostrums like Dolphinite.)

Jay Fleming

Jay FlemingSome snekker are dayboats with open-air layouts, while others have modest sleeping accommodations. The wind-shield is a distinctive feature of the type.

This noble heap of timber contributes substantially to the all-up displacement of 5,000 lbs, and this weight is essential to the Snekke’s charm. When you step aboard, the sensation of real substance is immediate. A crowd of people on the rail would heel the boat only a little. The Snekke dispatches a light chop and passing powerboat swill with a quiet “crunch.” This is no half-tide rock, however. The large outboard rudder offers precise control, and I had little trouble imagining myself running an inlet in a gale. As we motored into 15 knots of wind and short chop on the South River, exactly zero spray came over the bow. Experiments in punching the bow into the ugly wake of a big stinkpot were anticlimactic; the boat takes it like a duck.

The literal throbbing heart of the Snekke is a likewise noble lump of a Sabb diesel. Our test article is equipped with a two-cylinder, 22-hp mill built in 1968. Wallace had it restored and sent over from Norway to replace a more conventional 20-hp Westerbeke. The 450-lb Westerbeke, while ample to push the boat, was simply too light and required internal lead ballast to settle the boat on its lines. “Motor weight is essential to the character of the boat,” Wallace says. The old Sabb weighs 800 lbs.

Mounted inside a locust and cambrera box amidships, the engine gives the Snekke its special sauce. It has a lovely musical throb, not at all noisy, even with the box cracked a bit to help the external keel-cooler. “It puts my toddler daughter right to sleep,” says Wallace, who uses the boat for day trips off the coast of New Hampshire with family and friends.

As someone who is mostly allergic to engines on boats, I was enchanted with the Sabb. There is no reduction gear, and indeed no transmission. While there’s an electric start, you can spin the huge flywheel with a Victorian-looking hand crank, ease in the compression, and fire up the beast with maybe a half-dozen turns. Another crank adjusts the pitch of the 18″, two-bladed prop, giving you forward, neutral, and reverse at any engine speed without crunching the transmission. While we were at full throttle, Wallace reversed the pitch on the prop. There was a furious boiling under the stern and the boat came to a stop in a boat length or two, smoothly enough not to spill your coffee.

The gently rumbling Sabb pushes the Snekke to all of 61⁄2 knots. This is a stately and completely unfashionable pace. It is also the Snekke’s best feature. Our progress down the South River that August day felt luxuriously out of step with the big machines that were passing us. They were all hustle and mountains of bustle, acutely unrestful. Enjoying the pace of things aboard the wooden Snekke made me think of the Slow Food movement. The nautical analog—boats like the Snekke that are built by hand and get 25 miles per gallon—has yet to achieve the goateed hipness of Slow Food. Wallace admits that it’s been a challenge to sell the concept of Slow Boating, and that many correspondents have asked about a planing version.

Jay Fleming

Jay FlemingThe snekke, with its displacement hull, is not a fast boat. It moves easily through the water at a consistent 6 knots, sipping fuel.

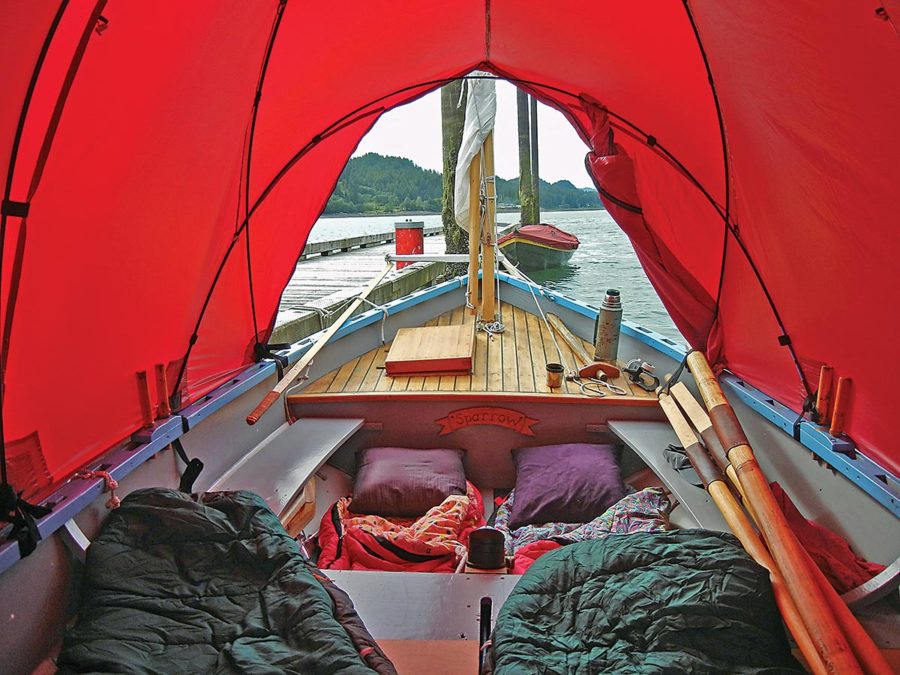

As he talked about how speed modifications would spoil the boat’s charms, my mind was wandering to thoughts of long coastal passages in the Snekke. It wasn’t just the seakeeping qualities or the long range under power. It was the layout of the interior, peculiar to the snekke type and mostly unseen in these waters. An automobile collector would call it a “cabrio coach.” There’s a decked area at the front of the cockpit, with two big settees port and starboard that extend up under the foredeck to double as very comfortable berths. Passengers sitting here would be dry in any weather. A quick-folding dodger extends the hard top to increase the covered area of the cockpit. Another bit of canvas closes in the stern to create a fully enclosed cabin, sleeping three adults or more. (See page 20 for more about the Snekke’s canvas treatment.)

The helmsman stands at the tiller on a platform aft of the engine box. The geometry is perfect, allowing a 360-degree view from the helm but genial proximity to the passengers under the hard top. There is no inside helm station. Wallace objects to the complexity this would add to his Thoreauvian powerboat. A hydraulic linkage with its oily fittings would not only literally disconnect the skipper from the feel of the boat; Wallace feels that being out of the weather disconnects the Snekke from its undecked Viking ancestors. “If I’m at the tiller, out in the wind and rain,” he says, “I’m going to be in the very best position to assess the weather and sea conditions and make the best decisions for the boat and the passengers.”

Even as the boat is admired wherever it ties up, Wallace wonders openly about the market for charmingly slow powerboats. I don’t think he should worry. There’s one constituency who will “get it”: all of the sailors who’ve thought about crossing over to internal combustion. A speed of 6 1⁄2 knots, all the time, no matter what the conditions, in fine style and perfect comfort, sounds like a great deal. Sailors understand the appeal of Slow Boating.

As we took up our mooring lines that evening, three small boys, damp and sunburned from a day of tubing behind an anonymous plastic sliver of a powerboat, swarmed the dockside. “Awesome!” “Cool!” was the chorus. “Does it have a propeller?” “Is it all wood?” Wallace invited the groms aboard.

“Would you rather go slow in a beautiful wooden boat, or fast in a plastic boat?” I asked the boys, still in reporter mode. After a pause, the answer came back: “Slow, in a beautiful wooden boat!”

There’s hope yet.

For more information, contact Andrew Wallace, Traditional Boatworks, www.traditionalboatworks.com.

Andrew Wallace/Tim Estabrook

Andrew Wallace/Tim EstabrookParticulars:

LOA 24′

Beam 8’6″

Power 22-27 hp diesel

Andrew Wallace/Tim Estabrook

Andrew Wallace/Tim EstabrookThe sailing forebears of the snekke are apparent in the lines of Andrew Wallace’s interpretation of the type. Snekker typically measure under 25’ overall, and are relatively firm-bilged and double-ended.

I really like the boat. What about the foredeck sharp rise? How would anchoring or tying up work?

Would you sell plans?

Kindest regards,

Brian Mosher

Nova Scotia, Canada

Brian, if you’re a good enough boatwright to make that boat: you don’t need plans.

Bought a boat that might have been its sister in 1974. Great, reliable and relaxing sea boat until the year I forgot to let it swell up tight before heading down Penobscot Bay. It was kind of amazing how much water can come in the above waterline planking. Wouldn’t mind a new one (or used). What’s the price range?

Speed is over rated. Slow down and enjoy the journey. This boat is a good example of just that. We need more like it.