John Summers

John SummersWith an open-cockpit layout, relatively high boom, and lots of seating, the Mirror is ideal for taking kids out.

If you’ve spent any time at all in sailing clubs in North America or Europe, chances are you’ve seen at least a few of the many dinghies drawn by the English designer and boatbuilder Jack Holt (1912–1995), who drew more than 40 boats during his long career, including the Cadet, the GP 14, the Hornet, an International 10-Square-Meter Canoe, an International 14, and the Rocket, which later merged with another design to become the Merlin Rocket. He was noted for his early adoption of marine plywood with a particular focus on dinghies that could be home-built by amateurs. Two of his more distinctive designs are the Enterprise (1956), with its baby blue sails, and the Mirror (1962), with deep red sailcloth derived from the newspaper’s signature color. Interestingly, the Enterprise (The News Chronicle) and the Mirror (The Daily Mirror) are, along with the DN Iceboat (The Detroit News), three small craft designs sponsored by newspapers that have gone on to great success.

To create the Mirror, Holt refined and improved two prototypes created by British do-it-yourself television personality Barry Bucknell. According to the international class association, more than 70,000 of these small dinghies have been built worldwide, and the Mirror is now an international one-design class overseen by the International Sailing Federation (ISAF). Mirror hull No. 1, EILEEN, was constructed in 1963 and is now in the collection of the National Maritime Museum Cornwall in Falmouth, England. Originally gunter-rigged, the class now also permits a Bermudan mainsail. The Mirror was an early design to employ stitch-and-glue construction. Home-built boats still use this method, but some professionally built hulls are also available in foam-sandwich fiberglass in the United Kingdom. The first generation of spars was all wood, but masts are now commonly aluminum.

John Summers

John SummersThe interior layout is simple and uncluttered. Auxiliary power can be provided by paddles or oars.

The dinghy measures 10’11” LOA × 4’7″ beam, with a board-down draft of 28″. Sail area is 49 sq ft in the main, 20 sq ft in the jib, and the spinnaker adds 47 sq ft. Complete and ready to sail, the boat weighs approximately 150 lbs, and capacity is 600 lbs. The racing crew is two, but the boat can easily accommodate three adults or an adult and several children for daysailing. Plans for this strict one-design are not commercially available, and Mirrors are sold either as complete kits, hull kits, bare hulls, or sail-away boats. The kits include everything except paint, varnish, and epoxy resin. Within the one-design specifications, the interior layouts have evolved in the years since the boat was first designed, and builders have some options in cockpit layout and the scantlings of individual components such as the yard of the sliding-gunter mainsail.

The conventional stitch-and-glue construction requires only basic hand and power tools. Work begins with clear-coating the hull panels with epoxy, especially where they will form the inside of buoyancy tanks. The builder next joins the fore-and-aft sections of the hull panels with butt straps, and then marks and drills them for wiring together. Small gluing blocks are attached to the bottom panels to aid in positioning and attaching the sides of the buoyancy tanks and the bulkheads later in the construction sequence.

John Summers

John SummersWhen racing, or looking for a little extra speed downwind, the Mirror can fly a spinnaker. Hull No.43756 has seen long service, so her deep red sails have faded a little.

The bottom panels are wired together first, followed by the aft transom, the bow transom, and the side panels. As always with a stitch-and-glue hull, it is crucial to align it with winding sticks and diagonal measurements before finishing the seams to ensure it is not wracked. The bulkheads and side tanks are fitted before the seams are filleted and taped, followed by the centerboard trunk and center thwart. The decks rails, and quarter and bow knees complete the basic hull. The rudder, daggerboard, and spars finish the build and are followed by hardware installation and rigging. The manufacturer of the kits suggests that boats can be constructed by builders with moderate skills and a reasonable assortment of tools in 150–200 hours. The U.K. Mirror Class Association website at www.ukmirrorsailing.com includes links to sites documenting particular Mirror constructions, and a YouTube search will quickly reveal posted videos of various build and restoration projects. The kits come with a comprehensive 50-page building manual.

The boat’s spars all fit inside the hull (at least with the gunter rig), and that, combined with a relatively light hull weight, means that Mirrors can easily be trailered or cartopped. They are readily carried or moved on a dolly for launching and retrieving from a beach or ramp. Rigging is quickly done, and boats can go from trailer to sailing in well under 30 minutes. A kick-up rudder means that it’s easy to sail off a beach.

John Summers

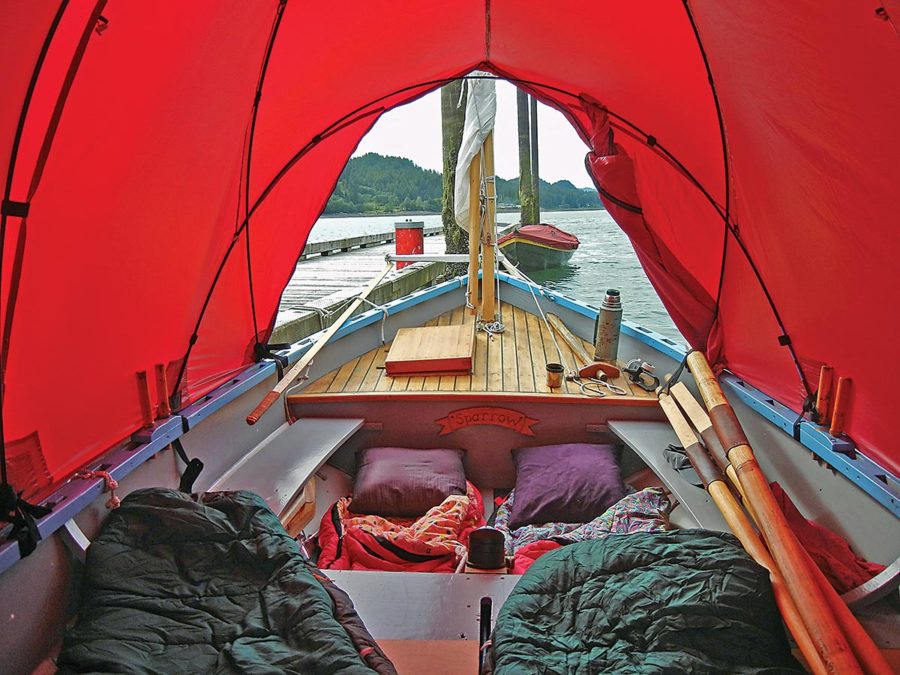

John SummersThe Mirror is an easy boat to singlehand, and some have made long cruises. Modest sail area and plenty of buoyancy allow Mirrors to go out in winds that would keep other dinghies on shore.

On the day I met with some members of the Ontario Mirror Dinghy Association to go sailing, the winds varied from very light to moderate, with perhaps a maximum of 8–9 knots for a time. Beautiful summer weather, to be sure, but it wasn’t a day to test the seamanship of the skipper or the mettle of the boat. I was assured by some sailors of the boat’s seaworthiness, though, as they shared stories of heading out on blustery days on Lake Huron or Lake Ontario long after other small boats had retired for the day. With 69 sq ft of working canvas, the Mirror is certainly not overpowered, but there are lots of other dinghies out there if you really want to go fast.

Under sail, the helm is light and the boat is well balanced. Like many small dinghies of traditional rig, the Mirror sails best a little eased and no higher than a close reach. The hull has an easy motion, but the pram bow means that she will tend to slap into a chop. We sailed with two average-sized adults for a time, and in the light air the boat balanced best with both of us on either side of ’midships, one to windward and one to leeward. Hiking straps are fitted for heavier weather, but we didn’t need to use them that day. Nothing is too far away in a boat only 11′ long, but those who habitually sail singlehanded might want to bring the control lines back to cleats on the center thwart for easy access. Serious racers will also want to double them up so that they can be reached from either side of the boat.

Basic sail controls include main and jib sheets, vang, and mainsheet outhaul. The wire shrouds are made off to chainplates, but the forestay is secured with a lashing to a pad-eye at the bow. Class rules permit it to be adjusted underway. The built-in buoyancy tanks go up either side and across the bow, offering a choice of seating positions. The gunwales are narrow, so serious racers or those planning on hiking out a lot might want to invest in padded shorts.

John Summers

John SummersMirrors are easily handled on beaching dollies, and can also be cartopped.

Class equipment includes both a whisker pole for booming out the jib clew downwind and a spinnaker, which is set and retrieved from a tapered mesh bag via a center retrieval line. Race upgrades include a multi-part block system for adjusting the forestay and up to an 8:1 purchase on the boom vang. As is often the case in one-design classes, racing competition can be fierce, and as one of the sailors I met when testing the boat said, “If you can make a Mirror go fast, you can make anything go fast.” Especially in the U.K., the boat has often served as a development platform for future Olympians and professional sailors.

The Mirror Dinghy is very popular in Europe and in Canada, but not as well known in the United States. This is a pity, because it is a durable and practical boat whose small size and easy handling make it perfect for those with young children and limited storage space at home. As a trailer boat or cartopper, the Mirror can easily be brought on vacation, and can also be rowed or, with minor modifications to the transom, fitted for use with a small outboard. In the right hands, Mirrors can also be capable small boats for cruising, and they have made some long passages under sail. The fact that all this can be had in an easily assembled kit that is available for less than the price of many other less-capable production dinghies is an added bonus. The experience of building and then using a boat together is one that can stay with parents and children for a very long time indeed. The distinctive red sails of the Mirror certainly deserve to be seen more often in North American, and especially in American, waters.

John Summers

John SummersWith its light draft and kick-up rudder, the Mirror is easily launched and retrieved in shallow water.

Mirror dinghies can often be found on the used-boat market in central and eastern Canada, particularly through the website of the Ontario Mirror Dinghy Association.

Mirror dinghy kits are available in North America from Mirror Sailing Development, [email protected].

General information about the class is available from the International Mirror Class Association www.mirrorsailing.org, where you will find links to national associations in Australia, Canada, Ireland, Japan, The Netherlands, South Africa, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

Mirror Sailing Development

Mirror Sailing DevelopmentMirror Dinghy Particulars

LOA 10′ 11″

Beam 4′ 7″

Draft board down 28″

board up 4″

Sail area

main and jib 69 sq ft

spinnaker 47 sq ft

The Ontario Mirror Dinghy Association website appears to be moribund. There are no classified ads any more and visitors wishing to acquire a Mirror are directed to Kijiji, eBay and Craigslist. The latest event listed was in 2016, although the copyright was updated to 2021. My Mirror is more than 40 years old and in rough shape.

“The Mirror is an easy boat to singlehand, and some have made long cruises.” An understatement as the example of Jack demonstrates in his book….4900km of high adventure!

The Unlikely Voyage of Jack De Crow: A Mirror Odyssey from North Wales to the Black Sea

by A. J. Mackinnon

Great little boats, I built two in my youth, now a very long time ago

These are fun boats to explore protected waters with. Years ago, Bliss Marine in the US sold kits for very little money. If you’re looking for a good read you must pick up a copy of The Unlikely Voyage of Jack de Crow by J.K. Mackinnon. A comedic account of his adventures sailing a borrowed Mirror dinghy from Wales to the Black Sea.

Unfortunately, there is no longer a source for Mirror Dinghy kits in North America. Kits, parts, and GRP boats are available through tridentuk.com. They ship worldwide.

One of our female members has two of them in our club in southwest Germany and I had the chance to sail with her. The Mirror is a really well designed little boat with a lot of capabilities for its size.