Benjamin Mendlowitz

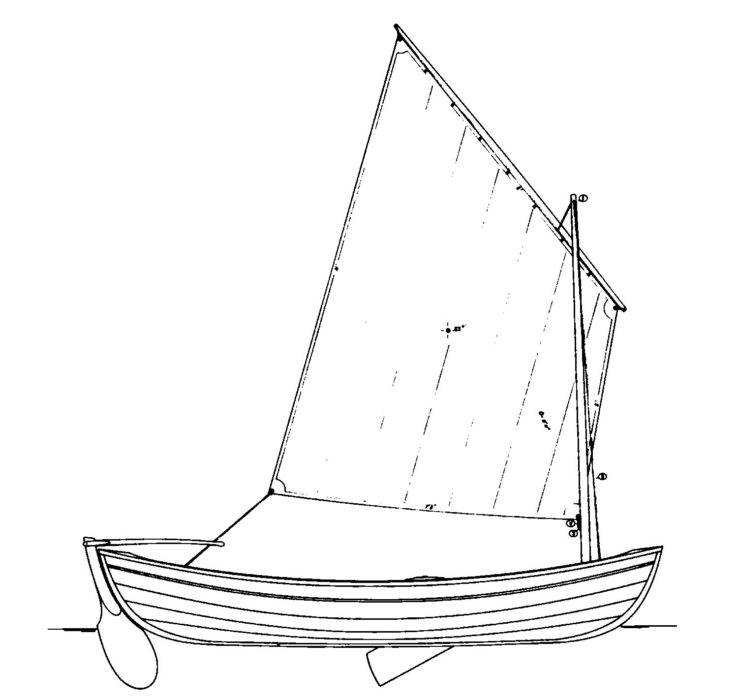

Benjamin MendlowitzBeach Pea is based on the well-known peapod type that evolved on Maine’s Penobscot Bay in the 1870s, but built of lightweight plywood. It retains the earlier type’s oar steering and simple sprit rig.

In the course of a decade, my appreciation for the Doug Hylan–designed Beach Pea has grown from a casual admiration to an abiding need. I first encountered the boat in 1997, when Hylan published in WoodenBoat a series of articles on how to build this glued-lapstrake plywood interpretation of the classic Maine peapod. In crisply drawn plans and clear words and photographs, he walked the reader through the steps of building the boat, and in the final installment included details on rigging and sailing.

Howard Chapelle, the great American boat historian, recorded the details of the peapod’s origins and use in his book American Small Sailing Craft. They were double-ended inshore lobstering boats that first appeared on the Maine island of North Haven around 1870 and quickly spread to other parts of the coast. The boats were symmetrical fore and aft, and sometimes carried small spritsails; they were typically steered with an oar when under sail. Original peapods were planked both both carvel (smooth-skinned) and lapstrake, and averaged about 15′ in length—though some were bigger and some smaller.

Hylan’s, at 13′, would look right at home among the ledges of Penobscot Bay—at least from a distance. (Hylan offers a 15′ version of this boat, too.) A knowledge able observer from 1870 making a close inspection of Beach Pea, however, would immediately notice that the boat has no frames. Their absence is a hallmark feature of the glued-lapstrake plywood method, which allows for the construction of relatively low-maintenance and neglect-resistant wooden boats. Which is not to say that neglect is desirable or something to be guarded against, but let’s face it: On modest maintenance budgets and limited time schedules, tenders often suffer for the bigger boat. I know many glued-lap dinghies in our area that are managed rather like rechargeable batteries, their finishes serving for several years until the boat looks unbearably bedraggled, and then the whole thing painted to like-new condition. It was, in fact, a benign amount of neglect in a used Beach Pea that allowed me to acquire one of these durable boats quickly and within budget a few years ago.

My wife, Holly, and I bought a 34′ cruising sailboat in 2008. Before the birth of our first son, we built a tender for it—a nice, small dinghy that would carry us all that first summer. With a wheel tucked into its bottom in the bow, this little boat was easily hauled up on the shore, and it remains a fine boat for its niche: We use it to this day for beach-launched ventures from a rocky shore in our neighborhood. But it’s too small for two growing boys and their parents to pile into for a trip from the mooring to the lobster pound. With the birth of our second son, it became abundantly clear that if we were to cruise in a safe and sane fashion, then a larger dinghy was needed.

Inspired by several cruising friends who have owned and loved classic plank-on-frame peapods as their primary tenders, and knowing that I wouldn’t be building a new dinghy in time for the next season, I scoured Maine Craigslist for candidates, and found several. As I was narrowing the field, an unexpected prospect appeared: A man in Massachusetts was selling a Hylan-designed Beach Pea, built from the pages of WoodenBoat all those years ago.

This was the perfect dinghy for my family of four. It rows easily with four grown people aboard, it tows well, and it’s much lighter than a traditional pod; we can carry it a short distance on the beach, and roll it longer distances on a beater fender. With no frames, it is very easily cleaned of the inevitable sand that accumulates in it. It has two rowing thwarts, plus seats in either end.

I called the seller, who had purchased it from the builder, and who was honest regarding its condition: He hadn’t used it for a while, and hadn’t had the space to store it indoors. Its finish was tired, but overall it was structurally sound. The Beach Pea, in fact, had sat upside-down in a garden for a few years, and ground contact had rotted the gunwale guard. It sounded as if there was a lot of fine boat lurking under a veil of old paint. Since the planks of a glued-plywood boat don’t dry up and split when the boat spends a few summers baking in the backyard, it all seemed like a good bet. The owner and I were 200 miles apart, but we were close on price, so we arranged to meet halfway. I bought the boat, and a winter’s worth of part-time sanding, filling, and painting—and a new canvas rubrail—yielded a tender that has become an integral part of our cruising kit.

Benjamin Mendlowitz

Benjamin MendlowitzWith its ease of beaching and good rowing and sailing, the boat makes a fine tender to a larger yacht—and a good daysailer in its own right.

Now, I realize that a run-down peapod will not be available to all of those who suddenly find themselves needing a good, capacious tender. Here’s what to expect if you want to build one of your own:

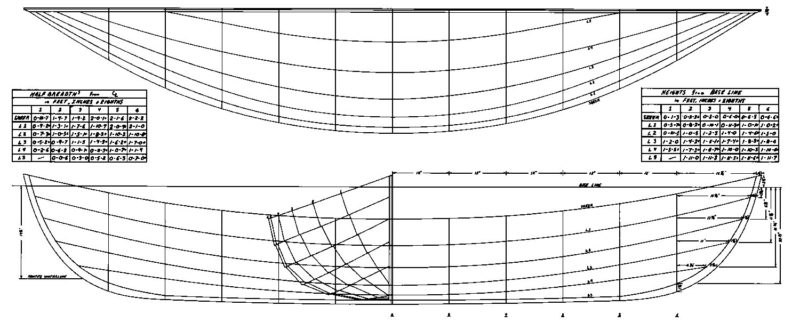

First, the plans are on six sheets, and include full-sized patterns, which means that the boat does not have to be drawn full-sized, or lofted. The boat is built upside-down on a series of molds erected on a ladder-back building jig. The Beach Pea has five ¼” planks per side and a 3⁄8″ bottom board. These are cut to their precise shapes, and their edges beveled to receive their glued-on neighbors. The job includes good, old-fashioned gains—the rolling bevels at the ends of the planks that make the skin transition from lapped to smooth as the planks approach the stems.

The stems are laminated from thin wood, and their sides beveled to receive the planking. A cap, or false stem, covers the ends of the plywood planks, the whole assembly mimicking the rabbeted stem of an original peapod. The short floor frames and thwart knees are steam-bent. A set of floorboards allows sure footing and dry feet, and a turned post under the center thwart offers a classic touch. For the beginner, none of this is terribly difficult work if it’s taken slowly and carefully, and all of it will aid in developing the skill and confidence needed to take on an even larger project.

The optional sailing rig includes a centerboard trunk, maststep, and partners (a hole in the forward seat). Hylan has specified a rudder for the boat, though in the interest of simplicity, he prefers to sail his own boat with an oar over the stern, the old-fashioned way.

Benjamin Mendlowitz

Benjamin MendlowitzThe boomless sprit rig makes life easy for passengers. The mainsheet, let slack here as the boat drifts to the beach, is turned through a block under the sternsheets.

The boat rows beautifully, either loaded or light. It has only one set of oarlocks, which might seem unusual to those used to moving to a forward thwart when there’s one passenger aboard. In the Beach Pea, you do move to the forward thwart with a passenger along, but you then spin around and face in the other direction, using the same oarlock sockets as before, so the stern becomes the bow. That’s the simple genius of making the forward and after ends identical, as described by Chapelle.

My boat was not built to sail, but I took Hylan’s rigged Beach Pea for a spin last summer. Based on that experience, I expect there’ll be a sailing rig for mine in a few years. Before I set out in Hylan’s boat, he gave me some quick instructions (switch the oar to leeward with each tack was the main directive), and I then drifted off the beach and lowered the centerboard, my three-year-old son Linus aboard.

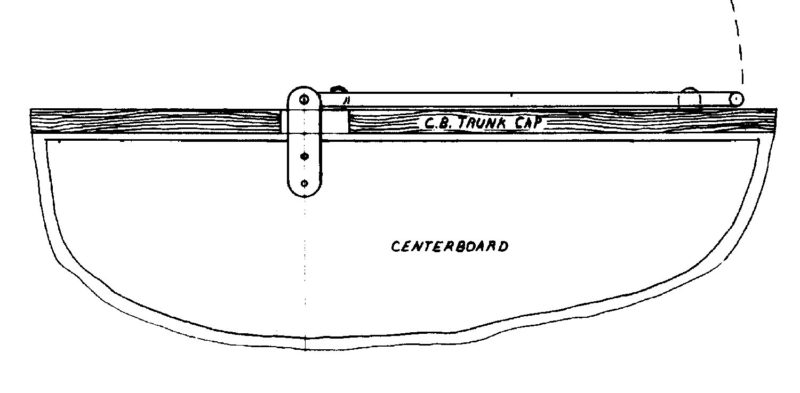

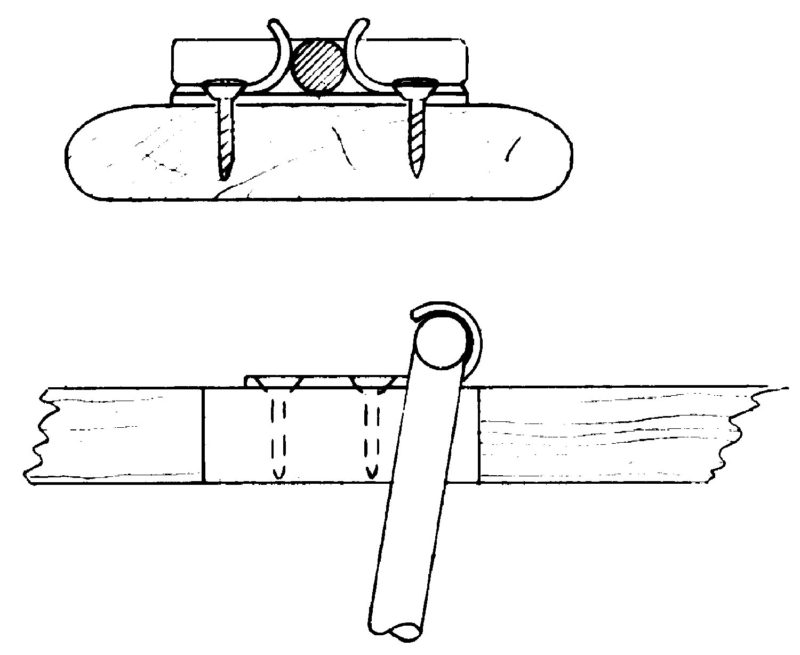

The centerboard arrangement deserves applause here. It’s controlled by a handle fabricated from bent bronze rod, which means you can push it down and into position positively, without having to rely on the weight of the board to sink it. And it raises up and locks into place just as easily, without having to rely on awkward purchase or a daggerboard. If you raise the board quickly enough, a squirt of water will shoot from the relief hole in the trunk’s cap, a phenomenon that elicited peals of laughter from Linus. I’m grateful that Hylan did not specify a daggerboard for this boat. Aside from the obvious and oft-cited dangers of hitting a rock with one deployed, I’ve always found them awkward to lower when sailing away from or in to a beach. The rod-pennant required just a flick of the hand. Plus, the board was always where I could find it, and not adrift, just out of arm’s reach, in the bilge. Daggerboards are simple to build and, in theory, simple to use. But I prefer a centerboard.

The steering itself is easy. This is not a pivot-on-a-dime hull, nor is this steering oar a pivot-on-a-dime rudder arrangement. But with a bit of forethought, you can be confident in the boat’s behavior, and thus thread through a crowded anchorage with ease. If you’re slow in stays, you can row the stern around.

In the early years of this design, Hylan envisioned it as sailable with no oar or rudder, thinking that shifting crew weight, sail trim, and centerboard position would steer it. And it might, but he admits to not having mastered this process yet—though he had some fun excitement trying.

Some tenders are pure utility boats, meant only to keep you dry as you suffer the trip from dock to boat. Beach Pea is more than that. It’s a great dinghy, for sure, but it’s a fine boat in itself, too. When ours isn’t swinging from the stern of our sailboat, it lives on a trailer in the driveway, and we often haul it to nearby ponds and rivers for family outings. ![]()

Plans for Beach Pea are available from The WoodenBoat Store. To correspond with the designer or to learn more about the larger version of Beach Pea, contact Hylan & Brown Boatbuilders https://www.dhylanboats.com/design/plans/beachpea_plans/

Beach Pea’s lines show a symmetrical hull fore and aft, just like an original peapod. The bottom three drawings show the details of the bronze centerboard “pennant,” which is held in both the up (top left) and down (bottom left) positions by bronze retaining clips.

Beach Pea Particulars:

LOA 13′

LWL 10’8″

Beam 4’4″

Draft (board up) 3′

(board down) 1’6″

Sail area (sprit rig) 55 sq ft

Sail area (lug rig) 54 sq ft

I built it in a class at WBS a couple of years ago. It is easy to build and looks great on or out of the water.

Great boat, great build story.

Seems like a perfect pairing of knowledge of both what you were after and how to get there in a straight forward fashion.

Congratulations!