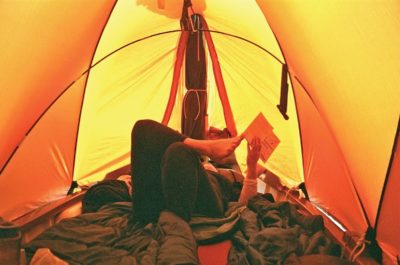

A Tent for Alaska

James Danner

James DannerJames Danner designed and built his own tent so he could more effectively use his Iain Oughtred– designed Caledonia Yawl for adventures in Alaska.

In Southeast Alaska, rocky beaches, insects, and a large resident bear population often make tent-camping on the beach an unappealing option,” James Danner writes from Juneau. “Having a boat tent has really opened up the family’s beach-cruising options. It can be set or struck easily while at anchor and has seen regular summertime use since it was created. My wife, Leni, appreciates the privacy the tent affords while camping on the water, and the kids just think it’s fun, bundled up in a sleeping bag rocking gently at anchor in their collapsible home away from home.”

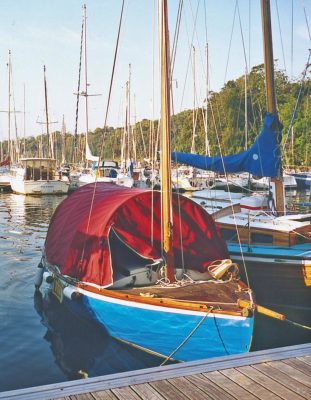

James Danner

James DannerClever uses of space give Danner’s boat enough room to cruise with his wife and two children.

Danner designed and built the tent for his Iain Oughtred–designed Caledonia Yawl, SPARROW, as a winter project. He based its structure on dome tents he had observed. “Then, the details were worked out over a full-sized mock-up in our basement, using plastic sheeting as pattern material for the various panels. Several Internet searches turned up all of the materials needed to complete the project.”

Danner’s tent is made from heavy-duty coated rip-stop nylon. Five segmented aluminum tent poles fit into pockets sewn into the tent, two of them forming an X across the cockpit from corner to corner. Three shorter poles form hoops to keep the ends open and support the center. The tent attaches to the boat at the gunwales with sewn-in web straps, and its ends are made off to the main and mizzen masts.

“The tent itself is made up of six individual panels that were stitched together with a UV-resistant thread with reinforcing patches added where the tent pole pockets are located,” Danner writes. “The ends of the tent are finished off with zippers to accept solid panels to enclose the cockpit area completely. The plan was to make screened panels that would keep the mosquitoes out while letting a breeze through, but in practice this has been unnecessary, since most summer evening temperatures here range from the mid-40s to low-50s.”

A Different Kind of Alaska

Rod Mort

Rod MortIn fair weather and for maximum ventilation, the tent that Rod Mort developed for his Don Kurylko–designed 18’ Alaska can spring outboard, away from the hull.

For his Don Kurylko–designed Alaska, an 18′ Whitehall type, Rod Mort of British Columbia had a specific idea in mind for a tent. “Don’s Alaska design came about partly as a result of a long cruise he did some years ago in his own Whitehall,” Mort writes. Kurylko lives in Nelson, B.C., which is far inland but within trailering range to gorgeous lakes and also to various sections of the Inside Passage. Beaches in the rocky, narrow passage are relatively scarce, however.

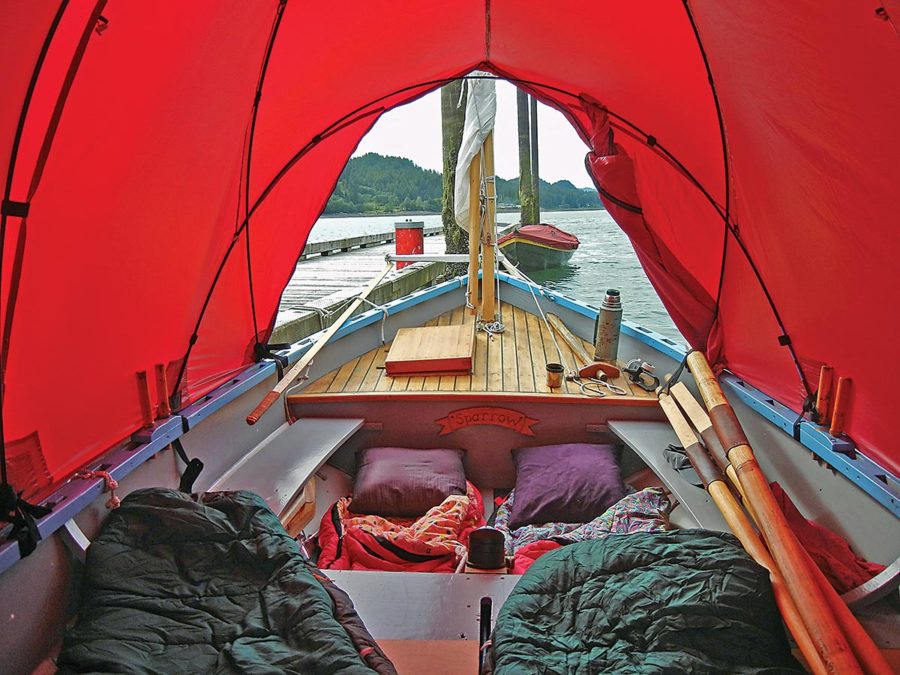

Rod Mort

Rod MortIn cold weather or when it’s time to ward off mosquitoes, the tent can be drawn in for a tight fi t to the gunwales and closed off forward, making a palatial space for the best kind of boat relaxation.

“The tent design is a prototype, but it has worked so well I haven’t had to change anything yet,” Mort writes. “My initial thoughts were to make something without adding any hardware to the boat. I wanted to avoid snaps on the rubrail or some such if I could. To facilitate setting up the boom tent, Don designed an extra maststep through the after deck. One thumb cleat on each mast holds up a ridge-line. The tent is secured to each mast first, then draped over the ridgeline and secured to the sides forward, amidships, and aft. Then the tent poles are added. Three short lengths of line on each side are attached to a loop on a pocket that receives the poles. The pockets and loops are made simply of webbing material. The tent poles needed to be quite thin to take the bend. In practice, I set up the diagonals first, going over the ridgeline and into the pockets on the other side. Two other poles are inserted into the middle pockets and over the ridgeline as well, one forward, one aft.

“Once the poles are in, the sides can be snugged down or left up for increased ventilation. The front and rear sections of the tent can be untied from the masts to open up cockpit space aft or forward. When the tent is secured all around, there is almost complete privacy.

“The fabric itself is coated rip-stop nylon, a very ‘quiet’ material sold here as a guide tarp. We added a couple of panels up front to cover the forward section completely, but we generally leave it open unless it’s quite cold out and the mosquitoes are bad. I have mosquito netting, which I have yet to try. It is suspended from the ridgeline and tucked in around the edges and poles. I’ve discovered that to get any sleep you have to keep mosquitoes as far away as possible.”

Windage is always a consideration in tent design and construction for small craft. “I have a 17-lb fisherman anchor with two fathoms of chain up front and an 11-lb Danforth off the stern,” Mort wrote. “The boat and tent act like a kite with this arrangement. I think about 15 knots of wind would be worrisome. I have an awning for those situations.”

The Randonneur

François Vivier

François VivierA veteran of many raids and a prolific small-craft designer from Brittany, François Vivier developed a large-volume tent for his Stir Ven design.

Not every boat design will come with a naval architect–designed tent as part of the specifications, noting panel dimensions and the exact types and locations of tie-downs. François Vivier, however, speaks from experience in the subject, having developed such a tent for his own boat. Because he designed his Stir Ven for competing in “raids”—weeklong sailing and racing events for open sail-and-oars boats—he worked out the details for himself. The result is detailed in drawings included in the plan sheets for the design. Stir Ven, a 22′ sloop (see Small Boats 2007), is one of Vivier’s most successful small boats, several of which would adapt well to raid-sailing or camp-cruising (see www.vivierboats.com). The French call these “randonneurs,” a term adapted for small boats from another kind of adventure, long-distance bicycling.

François Vivier

François VivierA zippered panel forward allows access to mooring or anchor lines.

“It takes about 10 minutes to mount the tent,” he writes. “The fi rst step is to put the ensemble boom, sail, and gaff on one side deck. For that purpose, the goose-neck has to be easy to disconnect. This gives much more free space under the tent.” The mainsail’s peak halyard is clipped to the transom and hauled taut, allowing the aft end of the tent to be made off to the halyard at the right height. The other end of the tent is made off to the mast. Vivier specifies five athwartships tent hoops, giving the tent a Conestoga-wagon look and ample interior space, including standing headroom. The hoops consist of sail battens of a type common on catamarans. “The ends are simply inserted into gussets closed by Velcro on one side,” he says. “At the centerline, there is a small rope, sewn to the tent, to attach the batten and keep it in position. For the end battens, there are some additional attachments.”

An unusual aspect of the tent is that those battens are long—about 11′ 6″, or 3.5m—but they stow alongside the cockpit under the side decks, where Vivier’s design already allocated space for stowing the boat’s long oars.

François Vivier

François VivierVelcro pockets receive long battens used for the hoops, which stow alongside the cockpit in space originally intended for stowing the boat’s long oars.

“The tent is lashed to the toerail, which is drilled about every foot,” Vivier wrote. “Eyelets on the tent are located in front of these holes. On each side, we use a single line to lash the tent to the toerail. A small cleat, also used for fishing lines, is used to belay the line end.” Because the boat has wide side decks, the cockpit stays dry. His cruising grounds in Brittany are mercifully free of insects, so no netting is needed, though it could easily be added to the tent doors. Vivier used a canvas-style cloth, but figures a lightweight waterproof cloth could be more satisfactory.

François Vivier

François VivierFood preparation and moving around are greatly enhanced by the full standing headroom, which any small cruising yacht owner would envy.

A door at the aft end of the tent provides access to the short afterdeck. Forward, a door to one side of the mast permits access to the foredeck for managing the anchor rode or mooring lines. With both doors open, ventilation is assured.

Stir Ven actually has a small cuddy cabin, but the tent extends and enlarges the living area, which can be a positive benefit when socked in by weather, or when four people are aboard. “Two people may sleep in the small cabin and two on the cockpit floorboards,” Vivier writes. “It is possible to stow bags and sails on the side decks, so four people may spend a weeklong raid. Of course, during the day, the cabin is almost full with all the boat and crew equipment.”

A Powerboat Cockpit

Jay Fleming

Jay FlemingFor hunkering down during inclement weather, a cockpit tent greatly expands the living area of a Snekke from boatbuilder Andrew Wallace of Traditional Boat-works in Canaan, New Hampshire.

by John Harris

In the year 2013, boatmen acquainted with the idea of a camp-cruising powerboat are one in a thousand. Don’t powerboat accommodations comprise decks stacked upon decks, surmounted by a flying bridge? But shipshape camping in open powerboats can be done, and it can be done very well.

Jay Fleming

Jay FlemingWhile the boat is under way, a retractable dodger gives guests shelter from the rain.

Thinking about canvaswork at the design stage helps with clean integration. Start, first, with a boat like Andrew Wallace’s Snekke, a deep, comfortable, 24′ inboard launch of traditional Norwegian origin (see page 44). Then add a handsomely proportioned cuddy, also idiomatic to the type. The neat windshield and high coamings around the cockpit create a solid foundation to which artful canvas-work can be anchored.

A single bent stainless-steel hoop is mounted at the rear of the cuddy opening. Folded away, it’s completely unobtrusive, even with the canvas attached. Flip the hoop back 90 degrees, and you have a dodger that roughly doubles the covered area of the cockpit. This dodger works beautifully under way to protect the helm without obstructing forward vision, and four adults may lounge in the cuddy out of the rain and wind.

Jay Fleming

Jay FlemingThe cockpit tent itself at-taches to the aft edge of the dodger and fi ts to the coam-ing for a quick setup.

The Snekke has sleeping accommodations for three or more adults on settees or the floorboards. To enclose the cockpit completely, another hoop folds up from its near-invisible housing against the aft bulkhead, supporting a swath of canvas over the helm station. Now you have a completely enclosed cabin with standing headroom aft. Elapsed time: just minutes.

Jay Fleming

Jay FlemingThe tent provides ample sitting headroom in the cockpit, and its zippers and snaps allow easy access. When the weather clears, the tent removes and stows easily.

Ventilation is essential for crew comfort. If the skies open up, there are small integral vents that will provide at least some cross-flow. (If the tent is being used as a cover for storage, this ventilation can also help guard against mildew.) A crew camping in a temperate climate would open a flap right aft and a forward window in the cuddy for a brisk flow of air at anchor. Screens zip into the openings to keep out stinging and buzzing things.

If it’s colder, Wallace points to a peculiar virtue of the inboard-powered Snekke: the 800-lb iron Sabb diesel, mounted right in the middle of the cockpit, radiates heat long after it’s been shut down. Free heat for winter camping!

The Snekke is a proper little yacht, and canvaswork in this class is not cheap if hired, or easy if you do it yourself. The bending of the hoops is best left to a professional shop accustomed to that sort of work. The intricate fabric shapes require careful patterning and siting of zippers and snaps. The result, rendered in the best UV-resistant yacht canvas, is as elegant as it is functional.![]()

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.