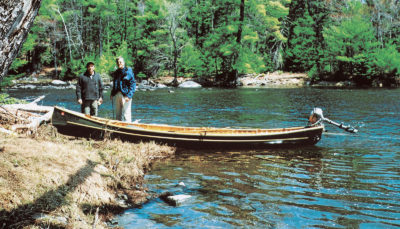

In this new “Y-sterned” canoe, the well-known wood-and-canvas canoe builder Jerry Stelmok has taken a rock-solid design, the E.M. White 20-footer, and adapted it well for a broad range of uses. It can carry a small motor on its narrow transom, it can be rowed very successfully from two stations, it can be poled with ease, and, of course, it may be paddled. It can carry much gear and still handle well, which makes it ably suited for fishing, perhaps its best use. This boat may be built by those who have some boatbuilding experience, or it may be purchased as a finished boat from Stelmok.

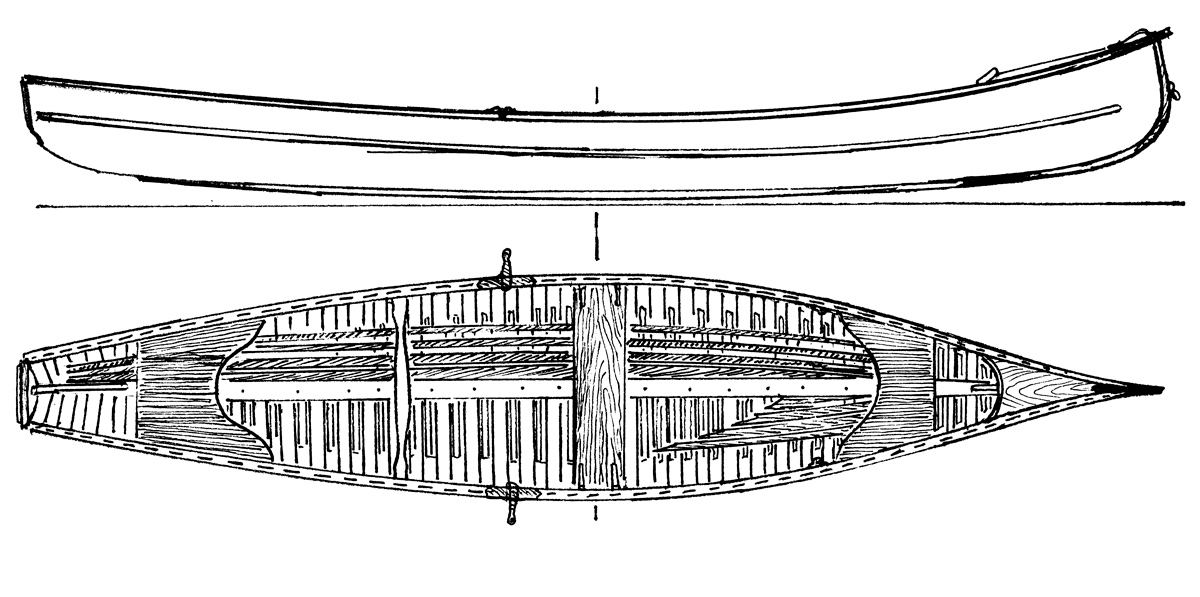

Edward M. White was a superb canoe builder operating in central Maine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His wood-and-canvas canoes were and still are held in high esteem by many who use them. Contemporary canoe builder Jerry Stelmok, also from central Maine, whom many consider the dean of the modern-day wood-and-canvas canoe revival, builds boats to E.M. White designs. He builds this Y-sterned model by using his E.M. White 20′ canoe form and closing in the stern of the canoe above the waterline with a transom rather than a conventional stem. The stem, however, remains below the waterline (unlike a simple square-sterned canoe); the hull, therefore, moves through the water like a conventional canoe, with the added benefit of a transom.

Stelmok attaches the gunwales to the transom while the hull is on the form. Then the hull is pulled from the form in the usual manner and completed before canvasing. To build this boat in this manner, you must first build a labor-intensive form that gives the boat its shape and provides a backing for attaching planks to the steam-bent ribs. If you are lost at this point, this may not be the boat for you!

Island Falls Canoe

Island Falls CanoeUnlike its square-sterned cousins, the West Branch canoe can carry a small motor on its transom while retaining the good paddling qualities of a double-ended canoe.

Stelmok has, in essence, substituted a transom for the conventional canoe end. His goal in doing so was to modify a well-proven canoe for low outboard power. He has put a 2-hp Honda four-stroke on it to great benefit, and says it will take a larger motor—but to the disadvantage of added weight. An electric motor would also work and would be quiet.

The idea for this boat, Stelmok says, came from similar although somewhat longer craft used by the salmon fishing community on New Brunswick and eastern Québec rivers. Rivers like the Restigouche and Miramichi have a uniform gradient and swift currents that make for fast descents and easily motorized ascents. So, a canoe with a small transom and small motor is a fine craft for fishing and navigating such rivers (on the Canadian rivers, both canoes and motors are somewhat larger). Stelmok refers to this canoe as his “West Branch” model, as it is so well suited to travel on that portion of Maine’s upper Penobscot River.

Stelmok typically equips the canoe with three seats—one in the stern from which the motor and associated gear can be managed, one amidships for rowing singly, and the third seat in the bow. From the bow seat one may: (a) fish if two people are fishing—two people may easily flyfish from this boat; (b) row if a second rowing station is equipped with oarlocks; (c) simply travel as a passenger.

This configuration of seat placement seems to be the best, although it makes it a better fishing than paddling canoe. It does paddle reasonably well, though, in part because the entry and exit lines of the canoe are nearly identical to a conventional canoe even though this boat has a transom.

Island Falls Canoe

Island Falls CanoeThe secret to the West Branch’s good paddling qualities lies below the waterline, where it’s a conventional canoe. Above the waterline, the topsides flare out to accommodate the transom.

Whereas the standard E.M. White 20-footer is 12 1⁄2″ deep and has a beam of 39″, Stelmok has stretched these dimensions a bit to improve its capabilities to carry a motor and fishing gear. He makes it 14″ deep and 42″ wide. Another small but significant and clever addition Stelmok adds are the spray rails. These are pieces of wood running longitudinally, nearly the length of the boat, and attached after the canoe has been canvased. Their purpose is to push splash from waves and chop away from the boat. Stelmok attaches spray rails to a variety of his boats and speaks highly of them. They make his Y-stern a much drier boat in windy conditions and on large lakes than it would be otherwise. In cross section the spray rails are roughly triangular.

Another excellent accessory in this boat is its floor rack. The rack consists of several slats of wood running longitudinally on the bottom of the inside of the canoe. Its purpose is to protect the ribs from the wear and tear of all the fishing gear, gas tank, etc. Gist: the floor rack takes the abuse, not the canoe (it can be removed for cleaning).

Canoes are reasonably long and sleek; they row reasonably well if rigged properly. Stelmok has taken advantage of this feature on the Y-stern by affixing a special “outrigger” oarlock near the middle seat. This outrigger was a 19th-century innovation and is currently sold for about $250 by the Shaw and Tenney Company (paddle and oar manufacturers of Orono, Maine). The outrigger oarlock flips outward when in use and back inboard when not. By flipping it outboard, one gains 3–4″ of width per oarlock, so when in use the oarlocks are about 48″ apart, an adequate width for rowing. Stelmok recommends 8′ oars (7 1⁄2-footers if the outrigger oarlock is not used) and generally uses those with spoon blades. The boat can be rigged with a second rowing station at the bow seat so two people could comfortably fish from this boat. And there would be ample room for all their gear.

Island Falls Canoe

Island Falls CanoeBuilder Jerry Stelmok poles the West Branch canoe through shallows. The 20′ E.M. White canoe, of which this boat is an adaptation, “has always been an exceptional poling boat,” says Stelmok. Note that oars are at the ready.

Stelmok’s boats are steeped in tradition and his craftsmanship is nothing short of superlative. The boat is canvas covered, the canvas filled and painted as is traditional for this sort of craft. It is then trimmed with either cherry or mahogany, which adds a lovely touch. Hardware (e.g., oarlocks) is generally bronze and the planking affixed to the ribs with brass tacks unless a customer anticipates saltwater use, in which case one should substitute copper tacks for brass.

Although Stelmok usually builds this boat as a 20-footer, it would work as an 18-footer, too. As a 20-footer, weighing between 110 and 130 lbs (depending on options and trim), it must be trailered, rather than cartopped.

Costs of building this boat would vary regionally and according to supply of basic materials like cedar for ribs and planking, etc. Stelmok has few problems finding good, clear stock in Maine and knows his mills and suppliers well. Whether one could be successful with suppliers in Nebraska or Algeria is open to debate.

The many capabilities of this special canoe make it an unusually attractive building project. But, beginners beware: You will need to start by building a form on which to build your canoe; then you must build a steambox in which to steam ribs for bending; and finally you must canvas your boat—not a job easily done well by beginners. But, if you are comfortable around a boatshop and all its tools, you’ll find this craft well worth the effort. The return (of pleasure) on the investment (of time) is an excellent ratio.

What a handsome craft this is to look at! The long, sweeping lines of the West Branch make it a delight to build, to be around, to show off, and to row, pole, motor, or paddle. If you have any concerns, though, about building this boat, you might consider taking a course with Stelmok, who teaches at WoodenBoat School in Brooklin, Maine.

In summary, this is an excellent, versatile, capable boat—an adaptation of a much-loved and highly respected design that is more than 100 years old. Although well-suited for fishing, it could have many uses. It is amply seaworthy for most lake and for gentle river travel. Go forth and build!

Cedar-and-canvas canoe construction is a laborious process at the setup stage; the building jigs are heavy and labor-intensive, and not ideal for one-off construction. But it’s rewarding, and readers wishing to learn more can read a multi-part series on the process in WoodenBoat magazine Nos. 141–143.

The West Branch Y-Stern Canoe is available from Island Falls Canoe for $6,900. Classes are available.

It sounds very interesting, but to be honest, I’m confused about the concept. If the transom has no influence under the waterline, the boat will not handle the outboard better then any other normal canoe. It will get out of balance.

With a traditional(?) OB canoe, the hull is chopped off to provide a transom that alters the underwater profile. This design chops the hull at the aft end of the waterline and flares the hull lines above the waterline to allow a transom wide enough for the transom.

I think Gerald is right. A Y transom, with it’s fine exit, won’t have the flotation to support an outboard hanging off the rear end. Especially if there’s a fat fella in the capt’s seat.

Ifn you want a motor on this boat, it’d need to be loaded like a freighter. You, a missus, and a weeks worth of camping gear including an actual kitchen sink.

But it sounds like it was designed exactly that way. Wider beam and higher freeboard: this baby was built to carry weight.

Very easy on the eye and highly utilitarian. Because of the overhead of canvas construction, particularly for a one-off, I’d be tempted to adapt this for glued-lapstrake construction.

First thing I thought of was, “What about a skin-on-frame version?”

It’d shake like a flag.

I am fascinated by designs that were conceived to accommodate the needs of the outdoorsman, (hunting and fishing). Although many of these designs are still being built by modern craftsmen, few ever see their intended use, due to being “too pretty”! I’d love to see one of these loaded down with decoys, a wet muddy dog, and shotgun-armed duck hunter! Although nostalgic, I feel that some of these old designs are still relevant!

I want this boat.

Yes , I want this boat badly.

Please build me this boat.

I need it .