Art Paine

Art PaineDesigner Chuck Paine enjoys a sail in his newly launched Paine 14. The boat is based on the venerable Herreshoff 12½, but is 45 percent smaller. The unstayed carbon-fiber rig weighs but 20 lbs, and the boat is easily trailered behind a mid-sized car.

The venerable Herreshoff 12½, which will turn 100 years old in 2014, is widely regarded as one of the—no, the—finest daysailer ever designed. Such a statement seems hyperbolic until one considers that the 12½’-waterline sloop has been in continuous production since the first one rolled out of the Herreshoff factory in 1914, and over those 100 years an average of 30 boats per year have been built. Herreshoff built 364 of them before the business closed and production moved to the Quincy Adams yard. Quincy Adams built 51 of the boats before Cape Cod Shipbuilding picked up the mantle, building 35 wooden hulls before switching to a long run of fiberglass ones. Doughdish, Inc. also builds a fiberglass 12½—an exact copy of the Herreshoff original—and Artisan Boatworks has built a few new wooden ones, and is willing and able to do more.

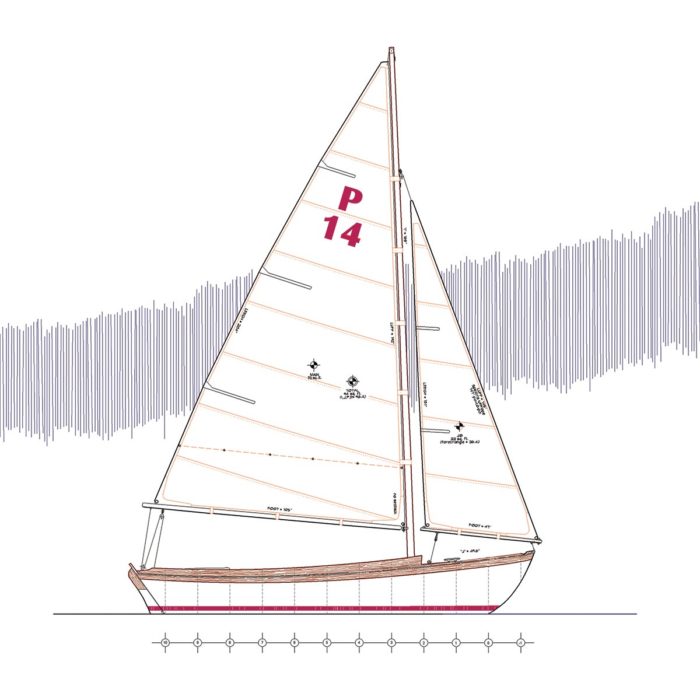

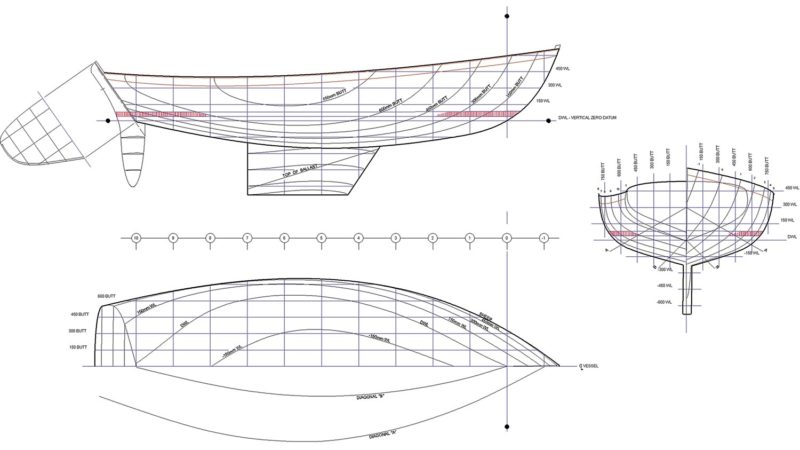

From the success of this legendary design came derivatives. In the early 1980s, Joel White conceived a shallower-draft centerboard version. He widened the hull slightly to offset the loss of stability caused by the shallower draft, but his Haven 12½ in the water is nearly identical to the original Herreshoff model. Designer-builder John Brooks has recently launched a glued-lapstrake plywood interpretation of the design, and Phil Bolger, at the time of his death in 2009, had just sailed and praised highly a sheet-plywood interpretation that he’d devised. And now Chuck Paine, who retired from active designing a few years ago, has just unveiled a scaled-down version of the boat—a beautiful 60-percent miniature of the classic Herreshoff 12½ with some decidedly contemporary updates, including an unstayed carbon-fiber rig and foil-shaped fin keel and rudder.

With all of the other H12½ derivatives on the market—and the new originals—I couldn’t help but wonder why the world needed another one. And so I asked Paine that question the day I met him for a sail aboard the new boat.

“I don’t know if it does,” he politely demurred. “I was retired and wanted a project.”

Paine and I had met near his home in Tenants Harbor, Maine, on a blustery August afternoon. Over the course of our outing in AMELIA, as the new boat is called, the answer to my question—the rationale for the new boat—unfurled slowly but decidedly.

“I didn’t want a boat the size of a 12½,” said Paine. He has ambitions to take the boat to Florida in the winter one of these years, and realizes that the original 12½ is just too much boat to tow those 1,500 miles behind his Subaru Outback. “This boat,” he said of the prototype Paine 14, “is so easy to put in the water.” How easy? Paine walked me through the launch procedure, which involved backing his custom Triad trailer down the ramp until the tailpipe of his Outback is just touching the water. Float the boat off, pop in the unstayed rig, strap the mainsail to the mast (more on that verb in a moment), raise it and the jib, and sail away. It takes two minutes, literally, as compared with the two hours Paine reckons it takes to launch and rig a Herreshoff 12½. And he should know, because he’s owned and loved an original 12½ for the past 40 years, and keeps it in pristine condition on a mooring adjacent to AMELIA’s.

Paine also did not want to tread on the business niche developed by Doughdish, Cape Cod Shipbuilding, and other H12½ shops over the past several decades. “They are making the world a much better place,” he said. “Plus, I didn’t want to mess with the world’s most perfect design.”

Art Paine

Art PaineAMELIA, the prototype Paine 14, sails in company with Paine’s Herreshoff 12½. In light air, AMELIA has a decisive speed advantage over her big sister.

Nautical linguists will note that, two paragraphs above, I wrote the rather lubberly phrase “strap the mainsail to the mast.” But I meant it, for Paine has come up with an elegantly simple method of affixing the luff of this sail to its carbon-fiber spar. It involves a series of five 2″-wide Velcro straps sewn onto the sail; they wrap around the mast, functioning as a sort of soft mast hoop. They don’t look traditional, but who cares? They’re almost invisible to the eye, and create a very secure attachment—with one slight drawback: There can be no strap above the jib halyard block on this fractional rig, as a strap so-placed would hinder the sail’s passage aloft. And so this portion of the sail is unattached, requiring considerable halyard tension in the 20-mph gusts we experienced that day. But, the halyard should be tight in these conditions anyhow, and so this loose portion of the luff offers a sort of halyard-tension gauge.

The club-footed jib is set flying, which means that it’s not attached to a forestay, because there is no forestay. It’s self-tending, making tacking extremely easy, as we’ll see shortly. The rig, with halyards, weighs about 20 lbs, and it fits into a socket made from fiberglass exhaust tubing that runs from the deck to the keel.

Paine handed me the helm as he dropped the mooring, and as we bore away and sheeted in, the boat accelerated noticeably more quickly than would a Herreshoff 12½. Paine noted that AMELIA, in light air, literally sails circles around his 12½ —which one would expect given the new boat’s underbody configuration. Paine was quick to point out that Nathanael Herreshoff designed the H12½ for the blustery and choppy conditions of Buzzards Bay—and that the older boat, once referred to as the “Buzzards Bay Boys Boat,” was meant as a trainer, and was thus conservatively rigged. The Paine 14 is not so conservatively rigged; although its hull is 45 percent smaller than the 12½’s, the sail plan, at 95 sq ft, is only 35 percent smaller. The racier, lighter, more trailerable Paine 14, says the designer, is meant for a different niche than the 12½. “I could sail this boat in the morning at Brooklin,” he said, casting his gaze downeast, “and then load it on the trailer and

sail it at Acadia National Park in the afternoon.”

Art Paine

Art PainePlywood bulkheads define the boat’s flotation chambers. The after chamber doubles as a stowage compartment, and has a watertight hatch.

After I tacked down the harbor, Paine took the helm in order to demonstrate a few of his observations about the new design. First, he called attention to the boat’s impressive short-tacking ability, the result of both the self-tending jib and, more important, the boat’s ability to accelerate out of a tack. There is simply no noticeable loss of speed as the boat comes through the eye of the wind and fills away on the other tack. AMELIA could, I believe, tack her way up a 20′-wide channel.

She also carries significant way. In the breeze we were sailing in that day, I would have expected AMELIA to stop pretty quickly when punched directly into the wind. But she does not—especially with 400 lbs of yacht designer and magazine editor as payload. Paine demonstrated this as we approached a moored boat that we could not quite point above. About 15′ away from it, he gently luffed AMELIA—more than a pinch but less than directly into the wind—and she continued, with virtually no pressure on the sails, to clear the mooring ball. Paine then bore away and continued on.

After this, we doused the jib to get a look at how she performs under mainsail alone. As expected, AMELIA did not point as high, but she still made clear and deliberate progress to windward. Under a reefed main and jib in 18–20 knots, she seemed to lose no speed but there was no need to dump the main in gusts, as there had been under full sail, when we kept a nearly constant bubble in the main’s luff—a so-called fisherman’s reef, Paine told me. With the mainsail reefed, gusts of breeze had no apparent effect on the helm, while with a full main it clearly loaded up, and required constant tending of the sheet. In fact, Paine rightfully chided me at one point for taking advantage of the handy mainsheet cam cleat on the deck of the after flotation tank.

As we made our way back to the mooring, we saw a fleet of 420s zipping around the buoys, with young athletic crews hanging from trapeze. “No hiking on this boat,” said Paine, whose sailing résumé includes an Olympic tilt in the Finn dinghy. “It’s an old man’s boat,” he said of the “14.” “But I’m an old man.”

Art Paine

Art PainePaine calls the Paine 14’s wood construction a “hybrid” method, because there are sawn plywood frames in the ends of the boat, while the mid-body is molded around a temporary jig. A production fiberglass version is under discussion.

The wooden Paine 14 is built of three layers of 1⁄8″ Spanish cedar or western red cedar. The planking is applied to forms spaced 7½” on center in the boat’s cockpit area, while permanent frames define the shapes of the bow and stern. “The frames don’t need to be there,” said Paine. “The boat complies with ABS standards without them.” He calls his approach to this boat’s molding “hybrid construction,” and he did it simply to ease the building process. The frames, which are about 2″ deep and made from a stack of marine plywood, are hidden in the flotation chambers—the after one of which has a watertight hatch, allowing it to double as a stowage compartment.

Paine built this prototype himself, out of wood, after an earlier version was built in New Zealand. He reckons, however, that the real market will be in fiberglass, as he estimates that a professionally built wooden one will cost about $70,000, while a fiberglass version will come in around $38,500. Plans are available to home builders.

Paine planked the prototype the old-fashioned way, which is to say that it was temporarily stapled, rather than vacuum-bagged. He then faired and fiberglassed the hull. The exterior received one layer of 10-oz boat cloth, while the visible cockpit area received a 6-oz layer, “for longevity,” said Paine. “I want this thing to be around 100 years from now.” If the Paine 14’s predecessor is any indication, that’s not too tall a wish.

For more information, contact Chuck Paine Yacht Design, www.chuckpaine.com.

The Paine 14’s sail plan is proportionally larger than the Herreshoff 12½’s, and the underbody is decidedly up-to-date with its foil-shaped keel and rudder.

Paine 14 Particulars:

LOA 14’0″

LWL 11’2″

Beam 5’3″

Draft 2’3″

Displacement 850 lbs

Ballast (lead) 385 lbs

Sail area 95 sq ft

D/L ratio 271

SA/disp ratio 18.79

Nice looking boat. I have no problem with the Velcro straps, but the airflow over the sails would be improved significantly if both were flown loose-footed. My sailmaker–who is legendary among wooden-boat afficionados–says that on a jib you lose about 30 percent of the drive by tying the sail hard against a boom. The gain from letting the main loose would be less, but still significant.

Really like your Paine 14. Wouldn’t mind having a small keelboat but my 17’x4.5′ lug-rigged boat with a daggerboard, LET’S GO, is just so handy to launch and rig. I’m also getting a bit old (83) to think about building another boat.

Bert Bowers