The Norwalk Islands Sharpies are the product of more than a century of evolution. Their pre-cursors are believed to have originated in New Haven, Connecticut, where there was a need for light, shallow-draft boats that could carry loads of oysters safely across bars to market. I say “believed” because there is some evidence that similar types were used in Ireland even earlier.

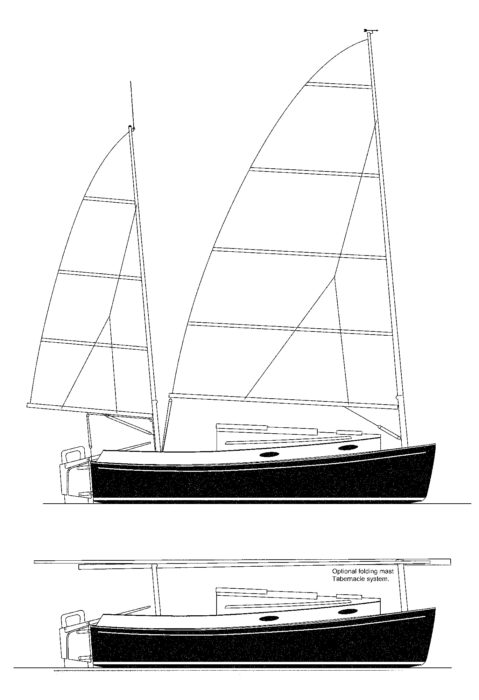

Working sharpies were flat-bottomed, slab-sided center-boarders rigged as cat-ketches with unstayed masts. They were perfectly suited to their environment, so when Bruce Kirby was thinking about a boat to use in his own slowly silting-in waterway at Rowayton, Connecticut, he turned to the local sharpies for inspiration.

The sharpie he drew for himself was a 26-footer (see Small Boats 2007). He was so pleased with her performance that he began designing a range of similar boats in varying sizes. He called them the Norwalk Islands Sharpies, and they’ve been around now for more than 20 years. In 1987 an Australian boatbuilder, Robert Ayliffe, came for a visit. The two hit it off, and when Robert returned home he set up NIS Boats to market the sharpies worldwide. About 250 Norwalk Islands Sharpies have been built from plans, over 60 of them in Australia. Their well-proven success is perhaps not surprising when you consider that they are designed by Kirby, whose credits include such diverse craft as the Laser, the Olympic Sonar class, and various Canadian challengers for the AMERICA’s Cup.

There are six designs in the NIS fleet, ranging from the 18-footer, which I sailed for this article, through 23′, 26′, 29′, 31′, and 43′. All except the two largest can be trailered, although the 29-footer is a ponderous beast on the road.

Traditional sharpies had their drawbacks. Their shallow, radically balanced rudders mounted under the rockered aft end sometimes made them tricky to steer. The NIS boats have retractable blade rudders mounted on the transom. The foil-shaped blades are designed to kick back against a bungee shock absorber if they hit something. You might think that the flat bottom would make the boats pound sailing to windward, but this is not so. They are initially quite tender before the hull shape firms them up, so even in light airs they sail slightly heeled. Owners report that once sailing, the boats present a chine to the waves, and the ride is remarkably soft and quiet.

The shallow draft means that you can take these boats into places that are off-limits to normal yachts. The NIS 18 draws 10″ with the board up. The 31 draws only 12″. In calm, sheltered conditions you can literally run the bow onto the beach and step ashore.

Courtesy of Stray Dog Boatworks

Courtesy of Stray Dog BoatworksThe Norwalk Islands Sharpies are built of readily available marine plywood, and a dedicated amateur should find the project both accessible and rewarding.

It’s probably fair to say that most people do not think of sharpies as seagoing boats. When Robert Ayliffe built his own 23-footer 23 years ago, he had no doubts about their capabilities. He had read the works of Commodore Ralph Munroe, who designed the sharpie yacht EGRET in the 1880s. The Commodore was one of the pioneer settlers of Miami, and his EGRET earned an enduring worldwide reputation while sailing on Biscayne Bay. Ayliffe was particularly impressed by an account of Munroe riding out a hurricane in EGRET without mishap.

Ayliffe’s first offshore passage in his 23-footer, CHARLIE FISHER, was from the South Australian mainland to Kangaroo Island, across the notoriously rough Investigator Strait. He and a companion beat to windward for eight hours in a gale that was recorded locally at 60-plus knots. “It was frightening,” he recalls, “but the boat sailed very well.” When they reached their destination, in true sharpie style they nosed up to the beach to rest and dry out. Other yachtsmen couldn’t believe that the little boat had been out in such weather. That was in 1988. Since then Ayliffe has weathered other Southern Ocean gales, including a protracted 45-knot howler in Bass Strait.

Courtesy of Stray Dog Boatworks

Courtesy of Stray Dog BoatworksThe deceptively sophisticated NIS 18 is easy to build and exciting and seaworthy under sail. The design includes the choice of two rigs: an unstayed gaff and an unstayed, fully battened marconi.

Bruce Kirby commissioned an independent marine consulting firm, Aerohydro Inc., of Southwest Harbor, Maine, to do an analysis of the righting moment of the 31-footer. He asked for righting moments for every 10 degrees up to 180 degrees (upside down). He was pleased and just a bit surprised when the results indicated that the 31 could roll to 143 degrees and expect to come back upright. A point of no return of 110 degrees is considered good for a small cruising boat; 143 degrees is remarkable.

The sharpies have fairly wide side decks combined with a high, crowned cabintop, so if the boat is knocked down the house supplies considerable flotation. The cockpit seats and the enclosed coaming seat backs also add buoyancy. Kirby notes that the self-righting chaacteristic applies to all sizes, but the smaller boats are more affected by crew distribution.

The Aerohydro study assumed that the hatches were closed. Ross Henderson, the Tasmanian owner of a 23-footer, was racing in Bass Strait recently when, through an odd combination of wind and wave, the boat was knocked flat. The masts were lying in the water; Henderson estimates that the boat was lying at about 100 degrees. The cockpit filled with water and, although the main hatch was open, not a drop went below.

While Robert Ayliffe hesitates to urge offshore adventures upon his customers, he says that with proper preparation and a skilled crew he has absolute confidence that these boats are up to the task.

Courtesy of Stray Dog Boatworks

Courtesy of Stray Dog BoatworksThe smaller Norwalk Islands Sharpies are uncluttered by sailbags and poles, since the two sails live on the booms and there are no bagged headsails needing stowage.

The NIS boats are built of marine plywood, sheathed with fiberglass and sealed inside and out with epoxy. Their simple, hard-chined hull shape places them within the abilities of amateur builders.

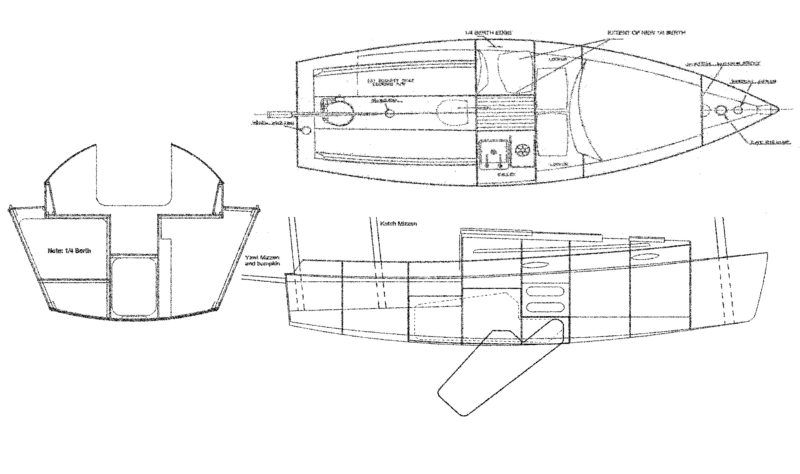

While the accommodations in the smaller boats is necessarily spartan, it is worth noting that the sails always live on the booms and, since the unstayed rig means that the boom can swing past 90 degrees, there is no need for spinnakers or spare headsails. Therefore, there are no sailbags down below. Some may find the presence of a centerboard trunk obtrusive, but on the 18-footer the accommodations have been left clear by cleverly placing the trunk slightly off-center and hiding it in the furniture. It seems to make no difference to the performance on either tack.

The cat-ketch is about as simple a rig as you can get. With the optional tabernacles, one person can step the unstayed masts easily. While the boat is being trailered, the sails can be left furled on the booms with the lazy-jacks and halyards in place, as the booms are attached to the tabernacles, not the masts. Upon arrival at the launching site, you simply winch the masts upright, slide the boat into the water, and go sailing. The masts on the original Norwalk Islands Sharpies were spun aluminum; there is now a carbon-fiber option, which is 35 percent of the weight of aluminum.

Having no jib, changing tacks on a sharpie is a matter of simply pushing the tiller over. The two sails look after themselves. You can sail these boats around in circles without touching a sheet, though there are control lines—vang, outhaul, and cunningham—for fine-tuning the sails’ shapes.

Courtesy of Stray Dog Boatworks

Courtesy of Stray Dog BoatworksThe Bruce Kirby–designed 18’ Norwalk Islands Sharpie is the latest and smallest in a family of boats ranging all the way to 43’.

The baby of the fleet, the NIS 18, originally had a single mast. The rig was recently reworked so that there is now either a ketch or yawl available. During a recent sail on board the first 18-footer with a ketch rig, I discovered that there were certain idiosyncrasies to get used to. Going to windward, you do not harden the mainsheet right in as you would expect to; instead, you ease it slightly so that the draft from the mainsail does not interfere with the mizzen. I found that the mizzen, sitting right in the middle of the cockpit, gets in the way a bit. The yawl, with the mizzen stepped on the transom, would free up the space nicely. There would be a slight loss of sail area and the sail would have to be sheeted off a boomkin, which could be prone to damage when maneuvering in marinas. At the time of writing, the first two yawls are being built, but none have hit the water yet.

When running wing-and-wing, one might instinctively choose to have the main setting normally and the mizzen slightly by the lee. Experienced NIS sailors do the opposite, running the mainsail by the lee and allowing the main boom to swing about 10 degrees forward of the mast. Wind hitting the mizzen is deflected into the main so that both sails keep filling beautifully.

There’s a lot to be said for a split rig in small cruising yachts. The center of effort is kept low, thereby reducing heeling. There are endless combinations available to balance the boat. One great advantage is that with the mizzen sheeted in hard, the boat will lie docilely head-to-wind while you take in a reef or go below to check the chart. The full-length battens ensure that the sails sit quietly.

These boats move in the slightest breeze. There’s no need for heavy, complicated, space-consuming inboard engines. Auxiliary power comes from an outboard motor mounted on the transom on the 18- and 23-footer, and operating through a well in the larger boats. But these motors don’t log many hours, for the Norwalk Islands Sharpie is truly a boat that is meant to be sailed.![]()

Plans and kits for the Norwalk Islands Sharpie from NIS Boats. This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2012 and appears here as archival material.

Phil Bolger indicated a shallow rudder with an end plate for many of his shallow draft boats. He claimed it improved handling significantly. I wonder if such a rudder has been tried on these sharpies?