You can walk across the Westport River in southern Massachusetts at low tide. It’s a mile or so across in some places, but the depth at full ebb is only 4′. If you want to cross that water with dry feet, then you need a shallow-draft boat. If you want to venture on that water to clam flats or to fishing grounds, then you need a shallow-draft boat with a reasonable amount of power and carrying capacity. Enter, the Westport skiff.

Photo by Matthew P. Murphy

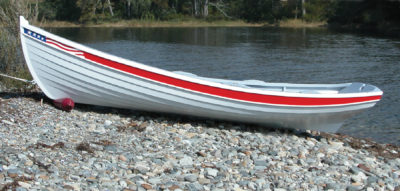

Photo by Matthew P. MurphyScott Gifford of Westport, Massachusetts, builds a flat-bottomed skiff called the Macomber 15. The boats are rugged, utilitarian, and good-looking, and designed by Scott in the signature style of his local workboats.

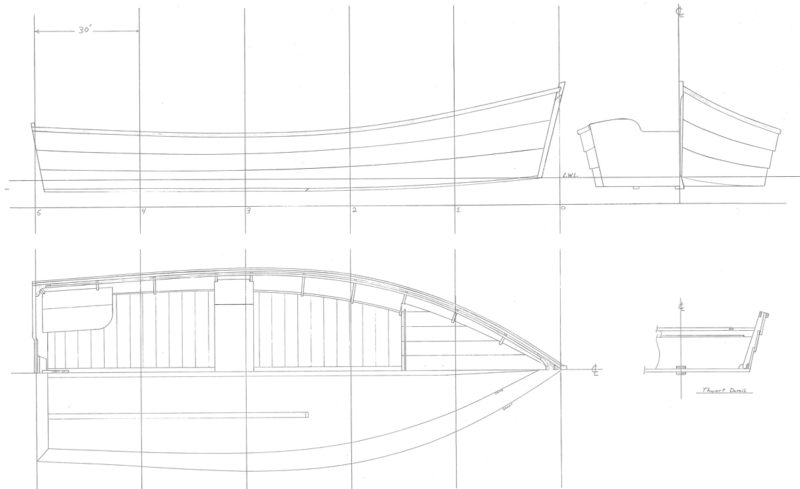

The Westport skiff is defined, roundly, as a wide, flat-bottomed, and rugged outboard-powered boat. It has a cross-planked bottom and lapstrake sides, and it evolved as a workboat for digging clams and for fishing on the Westport River. Early skiffs were sail-powered, and so had pronounced rocker, or longitudinal curvature, to their bottoms. They also had relatively narrow sterns. When people began hanging outboard engines on those narrow sterns in the 1940s, the boats ran with their bows high in the air, which obstructed the helmsman’s view forward. Evolution corrected the problem quickly: Wider sterns and flatter runs aft produced a stable, flat-running boat, and the vernacular Westport skiff was born.

Hundreds upon hundreds of these skiffs have been built in the past 60 years. Deacon Earle and Fred Hart were two of the most prominent builders, each man possessed of a unique, signature style. They’re both gone now, and the once-steady demand for their boats is diminished. But the demand isn’t gone, and a simple, rugged skiff built of local materials still has currency, as one young builder has been learning over the past few years.

Photo by Matthew P. Murphy

Photo by Matthew P. MurphyA pair of new Macomber 15s at rest, with an original Westport skiff in the background.

Scott Gifford grew up on the Westport River. His dad, Howie, built a wooden dory when Scott was a boy, and he spent a lot of time in that, and in other wooden boats. He went off eventually and got a degree in industrial and manufacturing engineering, but, he says, “I couldn’t get away from the water.” Scott eventually took up residence on the river, just upstream from the F.L. Tripp & Sons Boat Yard, where he works full-time as a project manager—dealing mainly in fiberglass. A brief tour of his house, however, reveals his true passions.

There’s evolution in progress here. On one wall hangs a series of half models: a sailing skiff on top, beneath that a flat-bottomed skiff, a boat of Scott’s own design that’s ideal for planing across the calm, protected water of the river. He’s built full-sized boats to this design. He calls the design the Macomber 15, and we took a spin in one last August, just a day after it attracted much attention at the WoodenBoat Show in Newport, Rhode Island. It’s fast—surprisingly fast for so heavy a boat. The slightest ripples on the water’s surface can be felt when the boat is zipping along—a rather pleasant effect, actually, but it suggests that the boat would be a handful in the wrong conditions, such as the ones that exist at the river’s mouth, and beyond. It’s a fact of life: flat bottoms, simple as they are to build, will pound when driven hard into a chop. To get out to the bluefish and bass, to venture beyond the river’s mouth, requires something else.

Consider the next model down on Scott’s wall from the flat-bottomed skiff. This one has a V-bottom—a shape that’ll be much kinder to the boat’s occupants in a Buzzards Bay chop. This is nothing new, of course; Scott Gifford did not invent the V-bottom. But what’s interesting on this wall of half models is that’s he’s recapitulated the evolution of local boat types. (There’s even a catboat at the bottom of the stack of models.) His V-bottomed model, in fact, looks surprisingly similar to the legendary bassboats of Ernest J. MacKenzie, built not far from here, for fishing among the rocky and choppy environs of the Elizabeth Islands in Massachusetts Bay. Scott didn’t set out to emulate MacKenzie. Rather, he seems to have arrived at this hull shape after being pressed by the same needs and longings of those who came before him: inshore watermen looking seaward. What better way to do this than to adapt a proven skiff for rough-water work.

Photo by Matthew P. Murphy

Photo by Matthew P. MurphyWesport skiffs were designed for the shallow expanse of the Westport River, where the ability to travel in thin water at reasonable speed is more important than the ability to make way in heavy seas.

The V-bottomed model will be the same above the water as the flat-bottomed model—except that it will have a deck. Scott envisions someday building one with an inboard diesel engine, though the prototype for this boat will carry an outboard. In late August, Scott was “99 percent sure I’ll build it this winter.” If he does, it’ll be built on the same building form—modified to yield the V-bottom—as are the flat-bottomed Macomber 15s.

Which, in my opinion, are exceptional boats. They must not be pushed beyond the limits of their intended environment—a protected river, a lake, a harbor. They are not meant to go to sea. But they are rugged—“overbuilt,” according to Scott—and they’ll last for a good long time “with nothing more than the usual proper care and maintenance that a well-built wooden boat deserves.”

This is no-nonsense construction. Scott begins with local logs of pine and oak, which he has sawn locally, and he then seasons the lumber for about a year. Planks are of pine, frames are of oak, and fastenings are bronze screws and copper nails, clenched at the laps and riveted at the frames. Transoms are of 1″ mahogany, splined and glued together, and further padded with a 3⁄4″ transom key, in way of the motor mounts. The bottoms are cross-planked, meaning that they are composed of short planks running across the boat, rather than along its length. The seams between these planks are given a “good smear” of Life-Calk, a flexible sealant that will come and go with the shrinking and swelling of the wood. This simple bottom construction is quite good at keeping the water out, but if a boat does leak, or if it takes some rainwater or spray, there’s an additional feature worthy of note: the boats are self-bailing when underway. The builder mounts a shop-made copper scoop on the bottom of each hull, this to relieve the bilge of water when the boat reaches speed.

The exteriors and seats are painted. Interiors are treated with boiled linseed oil. Wood so treated will weather to black in a few years.

Photo by Matthew P. Murphy

Photo by Matthew P. MurphyThe Macomber 15 is rated for 25 horsepower, but it will plane with much less power than that.

Scott Gifford’s Westport skiffs are rated by the Coast Guard to carry a 25-hp motor. They’ll do 32 mph with that power plant, compliments of the flat bottom, which skips over the river’s surface like a stone. The boat will also catch an edge—a chine—if you turn it hard at that speed, warns Scott. The result of such behavior would be a startling jolt. The builder recommends cruising at around 15 mph, and dialing back on the horsepower. “You can put a 25 on it, but you don’t need to use it all. I think 20 would be perfect, but nobody makes a 20 anymore. And then, considering further, he says, “15 would probably be ideal,” recalling that a 15 has got him and another guy up on plane, “no problem.” His musing on horsepower culminates with: “A Johnson 15, four-stroke, would be a very good match for this boat, weight-and horsepower-wise.”

“My goal,” writes Scott Gifford in one of his brochures, “is to bring back the tradition and simplicity that the Westport River skiff has had for the past few decades. I have designed the boats to be built from readily available stock and in traditional fashion.” A Macomber 15 built by Scott Gifford costs about $7,500. Customization and extras are, well, extra.

The Macomber 15’s lines are simple and good-looking. The boat is designed for relatively calm waters, but Scott Gifford, at the time of publication, was in the process of developing a model with a moderate V—a boat more suited than the Westport skiff to adventures outside the river.

You can order plans and finished boats from Macomber Boatworks, 95 Stillman Ave, Pawcatuck, CT 06379; [email protected]

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.