Kees Prins

Kees PrinsShallow draft, center console, room for a family, and an electric motor make this Rescue Minor, built by students at the Great Lakes Boat Building School, an ideal boat for Michigan’s Les Cheneaux Islands.

A couple of years ago, Bill Hunt of Aspen, Colorado, was looking for a boat with a very shallow draft. Hunt is a summer resident of Michigan’s Les Cheneaux Islands, and his home waters of Lakes Huron and Michigan currently have lower water levels than normal. Due to a combination of human and environmental factors the lakes are about 2‘ below mean level. As a result, many areas in the Les Cheneaux Islands have become inaccessible or hazardous for deep-draft boats. For his purposes, Hunt settled on a modified version of Rescue Minor.

William Atkin designed the Rescue Minor in 1942 as a military launch capable of rescuing wounded soldiers and sailors at speed from very shallow waters. The Atkin website (www.atkinboatplans.com) describes the design as a “tunnel-stern V-bottom Seabright skiff.” Besides the Rescue Minor, the Atkins designed several other tunnel-hulled boats, from a 17‘ utility scow to a 50‘ houseboat.

Atkin’s Rescue Minor is 19‘6“ long and with two people aboard draws only 6“, even at top speed. How is this possible for an inboard-powered craft of this size, considering the placement of the motor, shaft angles, prop size, and so forth? The answer is found in Atkin’s incorporation of a “box keel” into the hull. This type of keel takes the form of a smaller flat-bottomed boat beneath the much bigger main hull.

At the forward sections, the hull looks like a typical double-chined powerboat. About two-thirds of the way aft, however, the hull’s transition to the box keel becomes evident. The flat bottom continues in a straight line, forming the narrower flat bottom of the box keel. The upper chine continues in a fair curve to the lower transom corners. The lower chine, however, narrows and rises aft, forming the joint at the hull’s centerline where the top of the box keel sides meet the hull bottom. The result forms a tunnel stern.

The box keel comes to point quite a bit before the transom and just in front of the propeller. The propeller extends no lower than the bottom of the box keel, so it is protected in shallow waters. When the boat is at rest the propeller is partly out of the water. As the boat starts to move through the water, the water runs past the sides of the box keel into the cavity holding the propeller. The wash of the water in these channels immerses the propeller completely, resulting in a very easy motion through the water. The Rescue Minor is a fast boat that rests upright on a beach, moves smoothly through chop, and is very fuel-efficient; some owners report figures of over 25 mpg.

Kees Prins

Kees PrinsThe Rescue Minor’s box keel directs water to the finely formed horn timber that supports the propeller.

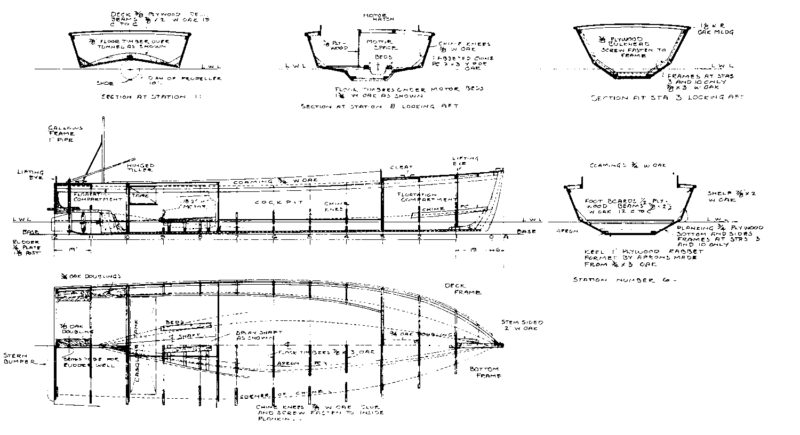

The second-year students in the Wood/Epoxy Composite program of the Great Lakes Boat Building School in Cedarville, Michigan, took on the construction of the new boat, NEPENTHE, as their major project for the year. Kees Prins, their instructor, considered the longstanding heritage of runabout designs of the Les Cheneaux Islands and the characteristics of the waters of upper Lake Huron in his revision of the Atkin design. He kept everything below the waterline exactly as drawn, but revised the topsides lines of NEPENTHE.

Prins introduced more flare in the bow, provided a bit more sweep to the sheer, and reshaped the stern, curving the transom and adding a pleasing amount of tumblehome aft. Hunt preferred to have a center console for better balance when driving the boat solo, so Prins fitted\ seating for four adults along with storage for their gear around this centerpiece.

Beyond these structural modifications, NEPENTHE also differs in its means of propulsion, using an electric motor instead of an internal-combustion engine. The motor for NEPENTHE is a 6.5-hp, 48-volt standard brush-type, which has a range of 24 nautical miles at 6 knots or 50 nautical miles at 5 knots. Given the pristine natural beauty of the area and the proximity of the 13 major islands in the Les Cheneaux archipelago, those ranges work very well with convenient charging in several locations.

Bud McIntire

Bud McIntireNEPENTHE’s center console hides three of her four batteries along with the charger and motor controller.

The motor requires 700 lbs of batteries, resulting in a challenge for Prins and his students to accommodate and balance them all in the hull. The four 255AH AGM (absorbed glass mat) batteries each weigh 175 lbs. The builders placed one battery in the forward compartment and three under the console. The boat floats nicely on her lines, although the battery weight caused the draft to increase from the as-designed 6“ to 8“, with a total displacement of 1,800 lbs. The class estimates that the plywood-epoxy hull itself weighs about 400 lbs less than a hull built exactly as drawn by Atkin, offsetting the additional weight of the batteries somewhat.

The students began lofting the boat in early October 2012. After lofting, they built a strongback and positioned along it 3⁄4“ Douglas-fir frames 24“ on center. The 1½“-square sternpost and the floor timbers of 3⁄8” marine plywood came next, followed by the laminated, curved transom. Installing the four laminated Douglas-fir chine logs, two at the top of the box keel and two at the chine, and the ¾“ marine-plywood bottom was a bit tricky, as the hull requires a good bit of twist in these pieces as they run from the stem to the start of the tunnel. The students determined that it could be done without breaking the plywood or having to kerf it. The tunnel’s shape at the after end of the hull required a unique horn timber, carefully crafted from sapele by one of the students to funnel the water coming past the box keel onto the blades of the protected propeller.

Next came the topsides. Instead of the ¾“ marine plywood specified on the plans, the class used glued strakes of 3⁄8“ marine plywood. After the planking was finished, the class reinforced the entire exterior with fiberglass cloth set in epoxy. Then they flipped the boat right-side up and work began on the interior. The sapele inner keel reinforces the rudderpost and propeller shaft. The students installed a stainless-steel rudder, as called for in Atkin’s original design, driven by a cable steering system.

There are watertight bulkheads forward and aft, which add strength and provide storage space and buoyancy in the boat’s ends. The flotation volume is sufficient, even considering the weight of the batteries and motor, for the boat to have positive flotation if swamped. To determine the placement of the batteries, the class considered the boat’s trim foremost, but also took into account the layout of the console and seating arrangement. They built plywood mockups of several console arrangements and conferred with the owner in deciding on the best design. Putting three of the four batteries and the motor controller and charger near the center of the boat under the tilting console resolved this key issue. Then they laid out the remaining seating around the console, making enough room for four adults to sit comfortably in the boat.

Kees Prins

Kees PrinsKees Prins’s modifications to the Rescue Minor included a center console, seating for four adults, electric power, and flotation compartments forward and aft.

The class launched NEPENTHE a couple of days before their June 6 graduation, so they had an opportunity to cruise the waterways and enjoy the quiet pace of the boat. Hunt and his family have been well satisfied with both the performance and the quality of the finished craft. He knew that the electric propulsion system would not get the boat anywhere close to its planing speed of 18 knots, but he preferred the quiet-running electric drive, combined with Rescue Minor’s size and shallow draft, as the best combination for him and his family. He has found that even in a 1‘ to 2‘ chop, the boat cuts through the water without pounding, tracks very well, and is relatively dry at cruising speed. Part of this stability and tracking is related to placing the heavy batteries low in the boat. Hunt has found that the partially submerged prop cavitates when reversing, and can be a challenge; however, he solves the issue by keeping weight in the stern when backing down.

In terms of improvements, Hunt has suggested that he would like to change to a more sophisticated battery system when the pricing becomes reasonable. A lighter battery, such as lithium-ion, or even a switch to an internal-combustion engine, would reduce the weight and raise the center of gravity with resulting changes in handling. It would also give the boat more range and speed. Given the space allocated for the conventional batteries, this is a change that could easily be made at a future date.

The project was a most rewarding accomplishment for the students as well as their instructor, and one that satisfied a very discerning client. And in the end, what could be better than a beautiful summer’s day gliding into shallow waters in which the family can splash and play, then silently heading for home with the lap of water on the strakes, the wind and the eagles above as the only sounds. Perhaps that’s why Hunt named the boat NEPENTHE, after an ancient Greek medicinal compound formulated to help people forget their cares and worries.

Plans no longer available from Atkin Boat Plans, plans will eventually be offered through Mystic Seaport. More information available from Great Lakes Boat Building School.

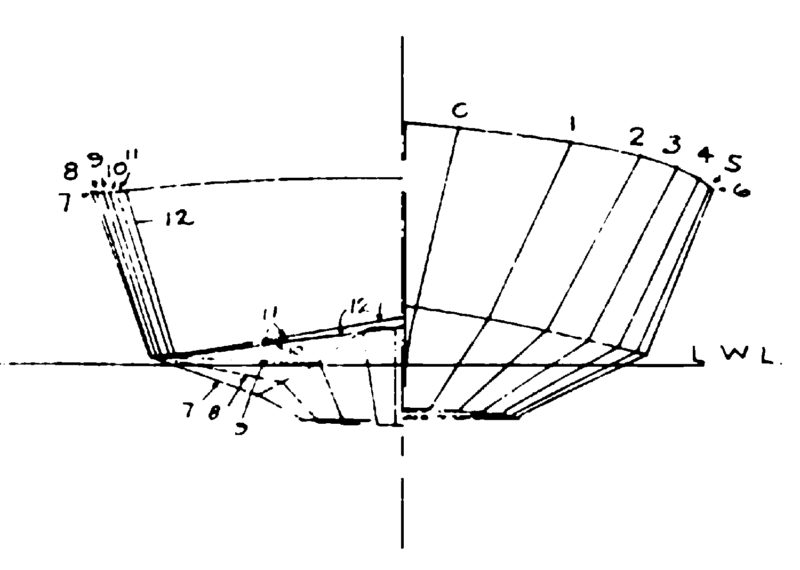

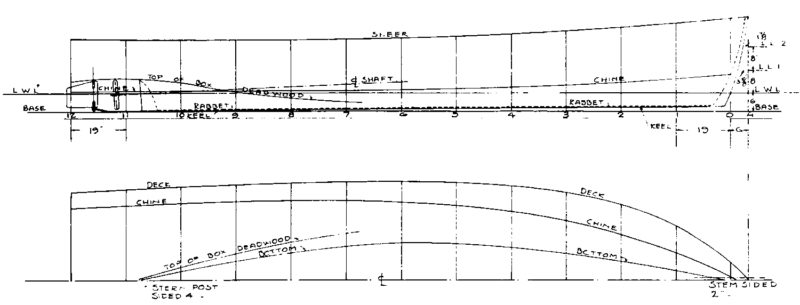

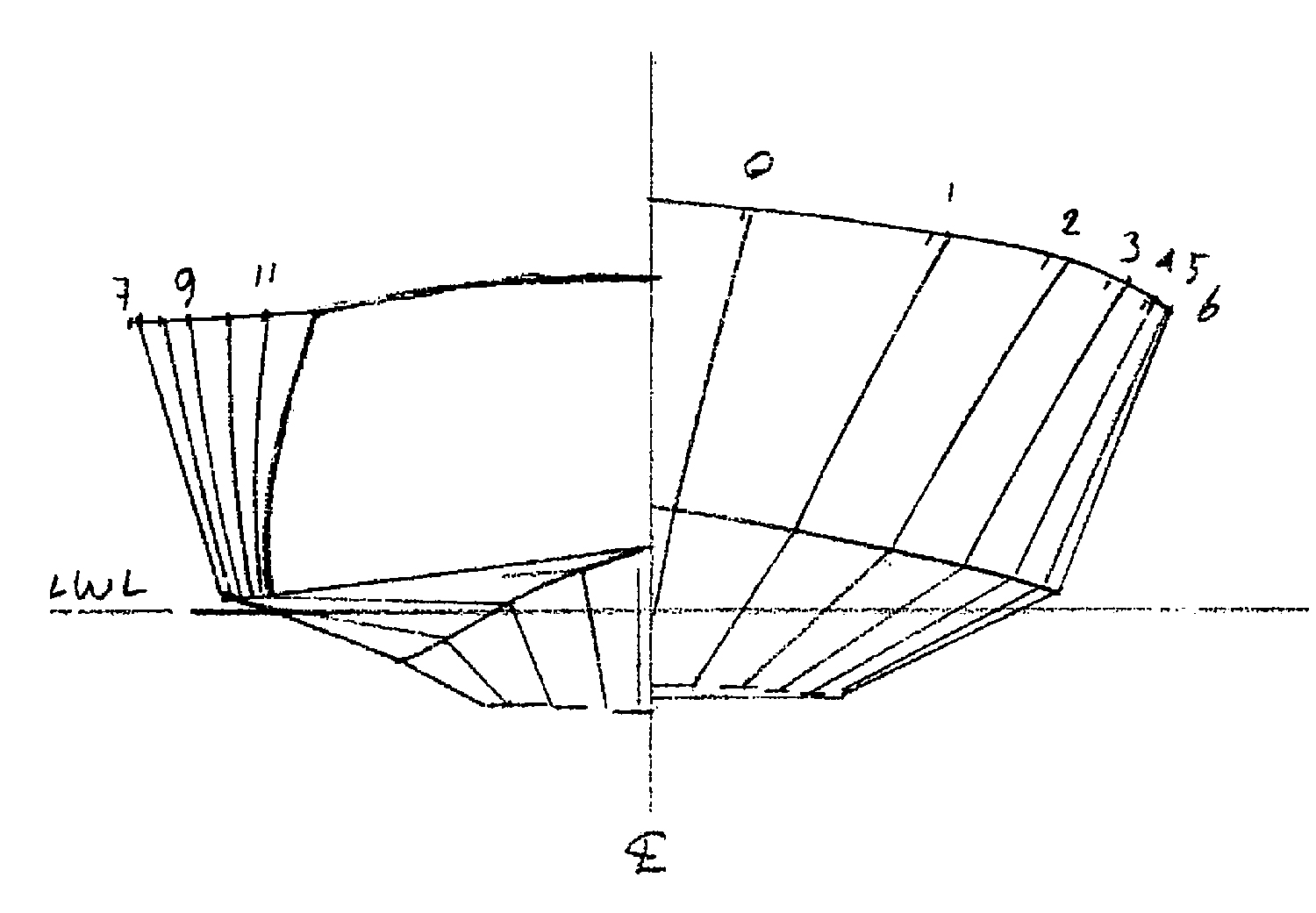

William Atkin

William AtkinThe sectional views below show how the underbody of William Atkin’s Rescue Minor changes drastically in shape from bow to stern. At right, the top body plan is by Kees Prins and the bottom one is by William Atkin. Prins kept the underbody exactly the same, but above the waterline he hollowed the bow sections slightly and added significant tumblehome to the stern.

William Atkin

William AtkinParticulars:

LOA 19′ 6″

LWL 19′ 0″

Beam 5′ 8″

Draft 8″

Displ 1,800 lbs

Power 48-volt, 6-hp electric motor

How can you do a whole article about Rescue Minor and not even mention Robb White?

Atkin designed quite a few boats with this bottom configuration (but without the “tunnel” effect). He called them Seabright skiffs. His work for the war included a 350′ tanker with the Seabright skiff underbody. Don’t know whether this was ever built. He loved the idea of decent speed with modest horsepower. Typically, he claimed speeds of around 17 mph using motors of very modest horsepower. “Happy Clam,” a plan I no longer possess (alas), was about his smallest at 17′, and called for a 6-hp motor. That appeared in How to Build 20 Boats, and his son John Atkin had a hand in the design (he may have actually been the sole designer).

Atkin also designed a number of boats, both round and V-bottom, that promised similar speeds. He always incorporated a bit of “hog” in the after part of the keel. I suspect that is what enabled the claimed speeds. These seem to be more of a fast displacement hull than a true planing hull.

The builders did a beautiful job of the reverse deadrise that forms the tunnel. I imagine this was the trickiest part of the build.

For Rescue Minor he calls for a motor of 91 cubic inches, but I don’t know how this translates to horsepower. The design as I have it was in vol. 38 of MoTor BoatinG’s Ideal Series.

I’m very happy to see Great Lakes Boat Building School mentioned in an article! They’re excellent people doing great work in Michigan’s upper peninsula, a very interesting place to mess about in boats. I am also a sucker for Atkins boats and electric propulsion and Lake Huron so this article is tailor made for me. Thank you!

I built a Rescue Minor several years ago. As with NEPENTHE, I modified the Atkin design to include a center console. My Rescue Minor, PEGGY ANN, uses a 25-hp diesel engine placed according to the plans. I have several observations:

1. With the engine placed according to the plans, the stern rides lower in the water than expected.

2. Atkin does not specify chine spray rails. They are needed.

3. With the flat bottom she does not ride a following angled sea well and tends to shimmy off the wave. I added a 2″ longitudinal keel from bow to end of box keel.

4. The biggest problem is the internal lower transom corners. Because of the tunnel design, any moisture that accumulates in these corners has no place to go. You need to include removable drains in these corners (these can be a thru threaded bolt) to drain these areas when you’re out of the water. Otherwise the boat will rot from the inside out.

5. She handles well enough but I would not want to take this craft out of protected waters. The freeboard is way to low. How Atkin could think that this vessel could take three sailors out to ships at sea in any kind of sea is just madness.