In 2019, I built a 14′ lug-rigged double-ender. It was lightweight, nimble, and smart looking, but lacked the gravitas to handle the Pacific swells and chop beyond the Santa Barbara breakwater. By 2021 I was ready for something just as beautiful but more capable, and spent a lot of time looking for a bigger trailer-sailer. The key constraints were space and weight. Our century-old cottage sits on a postage-stamp-size lot and our family vehicle is limited to 2,000 lbs towing capacity. The new design had to be less than 20′ long and under 1,500 lbs light displacement.

When I discovered François Vivier’s extensive portfolio of Breton workboat-inspired designs, I was really smitten by his Stir-Ven 22—a beautiful gaff-rigged lapstrake sloop with a roomy cockpit, a cuddy cabin, and a history of swift passages in European raids. The problem was it was just a little too long and heavy. Bring on the Stir-Ven 19, the newer, smaller sister Vivier designed with similar attributes but with a simple water-ballast system to facilitate launching and retrieval. At just under 19′ long, 7′ wide, and 1,200 lbs light displacement (without water ballast), it would meet my space and towing requirements. The designer estimates a build time of at least 700 hours, depending on the level of fit and finish.

Mark Gallo

Mark GalloThe water-ballast tanks either side of the centerboard trunk add a level of complexity to the Stir-Ven build but are a vital component in keeping the weight down for trailer-sailing. We oversized the structure of the centerboard trunk to accommodate our custom-made plywood-lead centerboard. Beneath the seats there are generous storage bins and astern of these is a large flotation tank; a second flotation tank is built in under the foredeck.

I had Maine-based Chase Small Craft, a Vivier licensee, produce a kit for the Stir-Ven 19, but I needed to find a site spacious enough to build the boat. I contacted local builder Eric Bridgford about the prospect of building the Stir-Ven 19 at his shop, Carpinteria Boat Works, and he agreed to partner in a collaborative effort where I would work alongside him.

Clint Chase supplied CNC-cut planks, decking, seats, and floors from 9mm okoume plywood, and bulkheads, centerboard trunk, and rudder from 15mm okoume per Vivier’s digital files. The centerboard was tricky to source. Vivier calls for a 260-lb cast-iron foil, but neither Clint nor I could locate a foundry in either Maine or Southern California willing to cast one. Chase came up with an elegant compromise. He sandwiched a 100-lb sheet of lead between okoume plywood sheets CNC-cut to the final foil shape. Eric and I satisfied the balance of the permanent ballast (160 lbs) by arranging lead ingots around the centerboard trunk below the cockpit sole in the water-ballast compartments.

A 67-page set of instructions guides the builder from start to finish and includes plywood-sheet diagrams of nesting parts, timber and fittings lists, photos of a fully rigged SV 19 with helpful details called out, and most importantly, CAD drawings of structural components including transom, bulkheads, centerboard trunk, rudder, and stem. A separate file has 20 pages of detailed drawings of bulkhead details for fillets, cleats and clamps, trim, and drains, as well as dimensional drawings of rudder, centerboard, spars, and sail plans. The pictures and plans provided good guidance and insight for the project.

Eric Bridgford

Eric BridgfordWith practice I can get the boat rigged, launched, and ready to go in under 45 minutes.

Once we had laid out and leveled the strongback, we bolted the bulkheads to their supports and turned our attention to the keystone of the structure: the centerboard trunk and water-ballast tanks. The trunk interior sides had to be ’glassed to resist abrasion, coated with graphite-infused epoxy, and supported by chunky end posts (slightly oversized from spec to accommodate our unique plywood-lead-sheet centerboard). The roughly 4′-long trunk, once complete with end posts, cleats for deck floor, and bottom logs, was substantial and strong.

We wrestled the assembly into the hull form and installed the remaining half bulkheads to stabilize it from the sides. The water-ballast tanks flank the trunk and provide 200 liters of capacity. They’re created by fitting longitudinal plywood pieces into bulkhead notches about 8″ from the trunk sides. A second set of longitudinal bulkheads aft of the trunk form the cockpit-seat lockers; the double-layered transom fits on these longitudinal bulkhead ends. We spent a lot of time filleting joints, being especially careful around the ballast tanks as they must be watertight. After the laminated inner stem was glued up, shaped, and installed we could lean back and appreciate the hull form before moving on to planking.

We hauled the sole and planks from the storage shed, having glued and faired the puzzle joints, and epoxy-coated them inside and outside. Eric took one side of the boat, and I took the other, and we proceeded to cut bevels and gains, starting with the garboards, and worked our way down toward the sheer. We managed to get each corresponding starboard and port plank end to line up, and installed and faired the outer stem. Once the skeg was installed, we laid down 10-oz fiberglass cloth on the garboards, filleted the lapstrake joints, and epoxied and faired the hull. While the hull was still upside down on the strongback, we painted it with one coat of primer and three coats of semigloss vintage marine blue. Friends and family helped us lift and carry the hull out from under the shed roof, flip it right-side up, and return it to its shelter.

Mark Gallo

Mark GalloThe attention to detail is key to the Stir-Ven’s appearance and functionality: ceiling slats forward of the cockpit seats look good and can also be used for lashing down gear. The spray rail around the foredeck—complete with limber holes—mirrors the cockpit coaming and works in concert with it to keep water out of the boat. The multi-purchase uphaul for the centerboard is housed on the side of the trunk in easy reach of the helm. The barber haulers are fed through the side decks to give simple adjustment control to the crew.

We scraped the stray epoxy drips and sanded all compartments, filleted more joints like the inside of the strakes, and ’glassed the water-ballast compartments around the centerboard trunk and underdeck buoyancy tanks at the hull ends. I painted the interior and applied nonskid to the cockpit-sole panels. Clint provided trim pieces rough-cut from red grandis wood, a plantation-grown eucalyptus variety native to Australia. The grain and reddish color look like mahogany but the wood is softer. We trimmed the interior of the boat first: the centerboard trunk, ceiling planks, and cockpit seat edges. After we installed the plywood deck, Eric cut, fit, and installed the more demanding trim pieces like the coamings, toerails, and rowing thwart. He eagerly took on the task of forming and brazing a bronze stemhead piece rather than sourcing from our pricey overseas supplier. I shaped the spruce bird’s-mouth mast and solid gaff and boom in the adjacent shed, and built oars out of poplar at my home shop.

The plans provide some guidance should you want to strip-plank over the plywood deck. At this point, nearly 1,200 hours into the project, I was eager to launch, so we opted to cover the deck in fiberglass and apply a light epoxy coating so the fabric weave would provide some grip, and finished it with several coats of light-yellow polyurethane paint. We flattened the gloss paint with an additive to reduce glare in keeping with my workboat-finish vision. To minimize preparation and maintenance of the eucalyptus trim pieces, I used a varnish alternative from Epifanes that does not require sanding between each coat. I chose to paint the spars a semigloss salmon color.

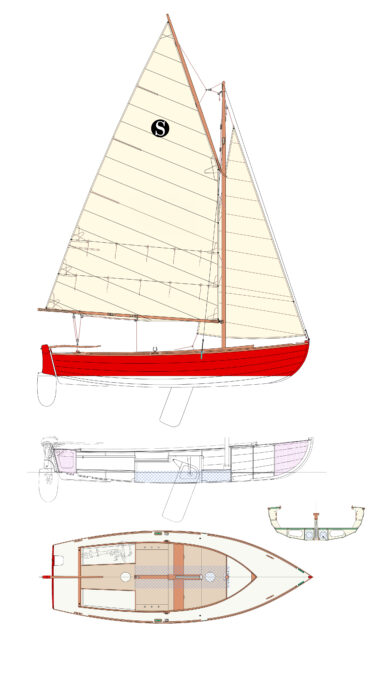

Courtesy of François Vivier

Courtesy of François VivierThe mainsail is almost 167 sq ft in area and the boom is high enough that the crew barely needs to duck when tacking or jibing.

After several solo excursions I can now raise the mast and rig the boat in about 30 minutes on the trailer. Backing down the ramp and launching, raising the sails, and lowering the foils takes another 10 to 15 minutes. So, if nothing gets tangled, twisted, or overlooked it takes about 45 minutes to get underway.

For anyone interested in overnight accommodations, the uncluttered cockpit allows two people to sleep under a boom tent (the rowing thwart is removable). The aft cockpit seat lockers are long and deep enough to swallow up loose gear like seat cushions, PFDs, thwarts, and even the electric outboard. Vivier has a nice-looking cabin version available as well.

Vivier designed the Stir-Ven 19 with safety a priority. In addition to buoyancy compartments at the ends of the boat, he provides port and starboard cockpit drain boxes which, when fitted with Elvstrom bailers, will drain a flooded cockpit whether underway or at the mooring. I built in the drain boxes but refrained from installing the bailers for the time being as my boat sits on a trailer.

Courtesy of François Vivier

Courtesy of François VivierDespite her modern construction, the Stir-Ven carries a traditional rig: a high-peaked gaff, loose-footed narrow-paneled mainsail with traditional points reefing, and a slightly overlapping jib, also narrow paneled to match the main.

The first time out on the Stir-Ven was, of course, thrilling for me as the co-builder—the gurgling of the water rushing by, the arc of the sails, the rush of the hull driving through the chop. At the dock the boat hardly heels to my movement, and underway it stiffens up well before the water reaches the side decks at 5 to 6 knots boat speed in 12 to 15 knots of wind. Initially the Stir-Ven’s upwind pointing capability was disappointing, but I was confident that with Vivier’s deep design experience there was room for improvement. With a little more reading and research, I made a couple of changes. I tightened the jib control lines (aka barber haulers) that Vivier specified to bring the jib clew inboard when going upwind, and tightened the jib luff as much as possible before leaving the dock. The boat points much better now.

I’ve sailed mostly singlehanded and found myself single-reefing the mainsail for winds of 10 to 12 knots. The big 160-sq-ft mainsail warrants early reefing to keep the boat from being overpowered. It tacks easily, even in light air, and we’ll point within 45 degrees of the wind. Designed with ample freeboard, the Stir-Ven 19 throws little to no spray going into a 15-knot breeze. I’ve had only one opportunity to use the water-ballast system and filling the tanks with an estimated 20 gallons of water (160 lbs) noticeably stabilized the hull. With time and experience I’ll get out in more blustery conditions and utilize the full water ballast and double-reefed mainsail, single-reefed jib combination.

Eric Bridgford

Eric BridgfordWith generous reefs in both sails and the ability to take on 440 lbs of water ballast, the Stir-Ven should be able to stand up to building wind strengths with ease.

The boat can be rowed, although I have yet to attempt it. If the wind dies, and the motor dies, then I’ll have no choice but to pull the 10′ 10″ oars out from under the side decks and give it a go. However, the nearly 7′ beam and 1,200-lb displacement will mean it’s a lot of effort, better suited to two people manning the oars side by side as Vivier depicts in his photo gallery. At the end of a day’s outing, I rely on the Torqeedo 1103 long-shaft electric motor (3-hp equivalent) to reliably and quietly drive the boat back to the launch ramp at half-throttle.

The Stir-Ven 19 has met my performance expectations and can be comfortably singlehanded or it will accommodate up to five adults in the spacious cockpit. It’s more stable and drier than an open dinghy in the Pacific swells, but is straightforward to tow, rig, and launch. While the water-ballast tanks complicate the build, they make it possible to keep the hull relatively lightweight for trailering and launching yet provide stability options should the need arise on the water. Bravo, François Vivier, for creating a beautiful daysailer with traditional lines!![]()

Mark Gallo is retired after a career in retail and catalog; he lives in Santa Barbara, California.

Stir-Ven 19 Particulars

LOA: 18′ 8″

LWL: 16′ 6″

Beam: 6′ 10″

Draft: 3′ 7″

Displacement: 1,170 lbs

Water ballast: 440 lbs

Sail area: 225 sq ft

Plans for the Stir-Ven 19 are available from François Vivier Naval Architect, PDF 456€ (approx. $459 U.S.) or printed 516€ ($560). Cutting files are available for 312€ ($339). Kits can be ordered from authorized partners.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us.

Boat looks beautiful!

Nice job, always liked the look of the Stir Ven. Would you mind asking what paint you used for the hull? I have a project boat, with water ballast by the way, that has a similar colored hull that I am trying to match. That color looks perfect.

Nice to see a small-boat builder in Carpinteria, where I grew up many years ago!

Thanks for the feedback Kyle. The paint is from George Kirby Paint Co. in New Bedford MA. The topside color is blue #19 in semi-gloss. It’s an alkyd-based paint rather than polyurethane. Maybe not as durable, but so far it’s taken a few hard knocks no problem. I followed George’s advice and added a splash of his conditioner to each working batch to facilitate flow.

Thanks for the info, I appreciate it. The blue hull with the tanbark sails looks fantastic!

Hope that you are enjoying sailing her.