Bruce Hollingsworth

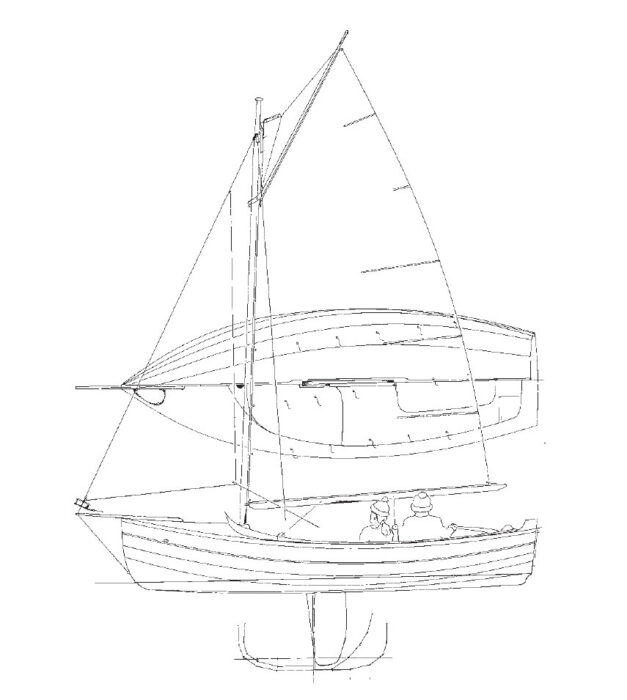

Bruce HollingsworthThe 17′ 4″ Pathfinder yawl, designed by John Welsford, is meant for serious cruising. One owner-builder in the designer’s New Zealand home waters spent 10 months living on his boat while exploring.

The Pathfinder, an open-cockpit yawl from New Zealand designer John Welsford, is a dinghy meant for some serious cruising. The 17′ 4″ LOD boat combines the classic looks of a lapstrake hull, the speed of a modern underbody, and the simplicity of a split rig to suit the singlehanded sailor. Any backyard boatbuilder with the desire to pack up some gear and head out onto the water for a few days would do well to take a look at this boat.

SPARTINA is the name of my Pathfinder. I don’t claim to be a boatbuilder or even a woodworker, but after 20 months of night and weekend work, the varnish glows brightly on her Douglas-fir masts, and a rich mahogany coaming rises to a peak on the foredeck. A dark green hull sets off the white sheer plank and the bright white main, mizzen, and jib made in a loft in Maine. If I can build a Pathfinder, just about anybody can.

Welsford is an ardent supporter of open-cockpit cruising, and he made his mark with the Navigator design, a 14′ 9″ yawl, a tried-and-true cruiser. About 600 sets of Navigator plans are in the hands of home boatbuilders, and about 250 of the boats are on the water worldwide. Another New Zealander, David Perillo, has done some of the most celebrated sailing in a Navigator, spending 10 months (that’s right, 10 months!) cruising the Fiji Islands in his Navigator yawl, the MARGARET H. His stories, full of adventure, knockdowns, and wide-open sailing, have drawn sailors to Welsford’s designs. Some of those sailors wanted something just a bit larger than the Navigator. Welsford says he had requests asking for a faster boat with more storage and a greater range. His answer was the Pathfinder.

From bowsprit to boomkin, Welsford has drawn the Pathfinder with safety, comfort, and storage in mind. The heritage for this design, Welsford tells me, comes from the cobles and other traditional boats of the northeast coast of England. Those lapstrake boats are launched off the beach and sailed well out into the waters of the North Sea, “a seriously rough part of the world,” he says. The Pathfinder pays homage to those classic North Sea boats with a narrow forefoot that slices through the water, a hull that broadens amidships for stability, and a nice tumblehome as the upper planks slope inward from thwart to the slightly raked transom. Beneath the waterline, Welsford has borrowed some of the shape used on his transatlantic racers to give the Pathfinder some speed.

Steve Earley

Steve EarleyBruce Hollingsworth at the tiller of SPARTINA on Core Sound.

For safety, Welsford has built an incredible amount of buoyancy into the Pathfinder, with watertight compartments in the bow and beneath the seats of the aft cockpit, the thwart, and forward cockpit sole. These watertight spaces serve double duty as storage areas accessible through deck plates. Under the aft cockpit seats of SPARTINA, I store my first-aid kit, batteries, extra line, spare fittings, spark plugs, and fishing tackle and still have plenty of room left over. The thwarts provide the largest watertight storage, the perfect spot for food, clothes, books, and cameras. Just forward of the thwart, two more deck plates give access to the ballast area where there is extra room for the tool kit, spare anchor, and almost 10 gallons of water.

Bruce Hollingsworth

Bruce HollingsworthSteve Earley cooks dinner for two on board SPARTINA on Core Sound, North Carolina.

The Pathfinder’s wide side decks and coaming hide cruising gear from the sun and salt spray. I keep my foulweather gear, cook kit, oar, boathook, camp stove, and fenders lashed up along the hull under the side decks. Beneath the foredeck is room for the anchor, portable toilet, boom tent, and sleeping bag. It is amazing how much storage Welsford has crafted into this boat. Room to keep things tucked away is more than just convenience on a small boat; it is a matter of safety. I’ve got a clear path forward to the halyards and anchor, with no worries about tripping over gear. An inboard well for the auxiliary outboard preserves the graceful lines of the lapstrake hull. While this keeps the classic look of the hull, I see it as yet another safety feature. I don’t have to lean out over the transom to add fuel or change a spark plug. All of that can be done from inside the cockpit.

Just as Welsford brought traditional styling to a modern hull, he also adapted traditional boatbuilding to suit the garage boatbuilder. In his plans, he shows how common tools, marine-grade plywood, and epoxy can be used by someone like me, a complete amateur, to build a fine boat. Welsford tells his builders, “Don’t sweat over the last tiny bit; build your boat, paint it, and go sailing.” Knowing well that many of his builders don’t have skills or patience for hair-thin tolerances, he says a fair curve is more important than a millimeter or two here or there.

Steve Earley

Steve EarleySailing under a small-craft warning on Tangier Sound.

A metric tape measure is probably the first tool worth buying, as Welsford’s plans are in metric measurements. Beyond that, mostly common tools are used in Pathfinder’s construction. Screwdrivers, hammer, drill, jigsaw, hand plane, sander, and a bucket full of clamps will get you going.

The 12 sheets of drawings in the Pathfinder plans have scaled drawings for seven frames to be cut from plywood. The frames and centerboard trunk are then mounted on a bottom panel scarfed from two sheets of plywood. The promise of a boat shows as stringers are bent into place around the frames. Plywood planks are dry-fitted to the stringers and trimmed to fit from the bottom of one stringer to the top of the stringer above. The most challenging plank is the garboard between the first bulkhead and the stem where there is a reverse curve in the lowest stringer. Getting the plywood to match that curve is a matter of strength, leverage, and patience. But once the plank is drawn into place, there is that beautiful forefoot that cleaves the water with a slight hollow as it flares upward to the next overlapping plank. Once that plank is epoxied in place, the rest is easy. With the hull completed, I barely looked at the plans and simply cut the decks, seats, and cockpit sole to fit.

Need advice in the middle of the build? Go to the John Welsford builders group at Groups.yahoo.com/-group/jwbuilders. Past, current, and prospective builders all take part in the discussion of understanding plans, techniques, and design for Welsford’s boat. Ask a question, and more likely than not Welsford himself will chime in with advice or opinion.

In fact, the discussion group is the place to talk with the designer about changes to his plans. I made a handful of changes to suit my tastes and sailing experience. I left out the bow anchor well on my boat. The well is 4′ from the cockpit—farther than I would want to stretch to reach the anchor in rough water. I find it simpler to keep the anchor in a bucket under the foredeck. For increased ballast and stability, I substituted a 1⁄ 2″-thick, 100-lb steel plate for the weighted wooden centerboard shown on the plans. The masts and spars in the plans are made of aluminum tubing, but a classic-looking hull like the Pathfinder deserves wood. So, like many Welsford builders, I built wooden masts, booms, and gaff from Douglas-fir.

The Pathfinder performs better than I had hoped it would. With a light breeze, she moves along nicely; with a stiff breeze, she flies. The hull, feeling much wider than it really is, has a solid feel as the boat heels to a comfortable angle and holds her position. The narrow forefoot cuts through the water, the flare of the bow pushes the spray out and away on all but the roughest of days.

SPARTINA has proven herself time and again. I’ve sailed across miles of deep water during small-craft warnings, a single reef tucked in the main, and felt perfectly safe. I’ve sailed backwards—a nice trick that can be done with a yawl under mizzen only—across shallow sand flats. A good friend and I have packed the boat with food, water, tents, sleeping bags, clothes, cameras, and fishing rods for a sixday, 100-mile cruise in the sounds of North Carolina. All that gear on board, and we still had plenty of space. Whether miles from shore or in shallow water along a barrier island, the Pathfinder feels at home. I can’t imagine a better design—especially one that I could build—for open-boat cruising.

Pathfinder plans are available from John Welsford. For more information and other plans, visit John Welsford Small Craft Design.

Pathfinder Particulars

LOA 17′ 4″

Beam 6′ 5″

Weight (with motor) 485 lbs

Sail area 162 sq ft

John Welsford

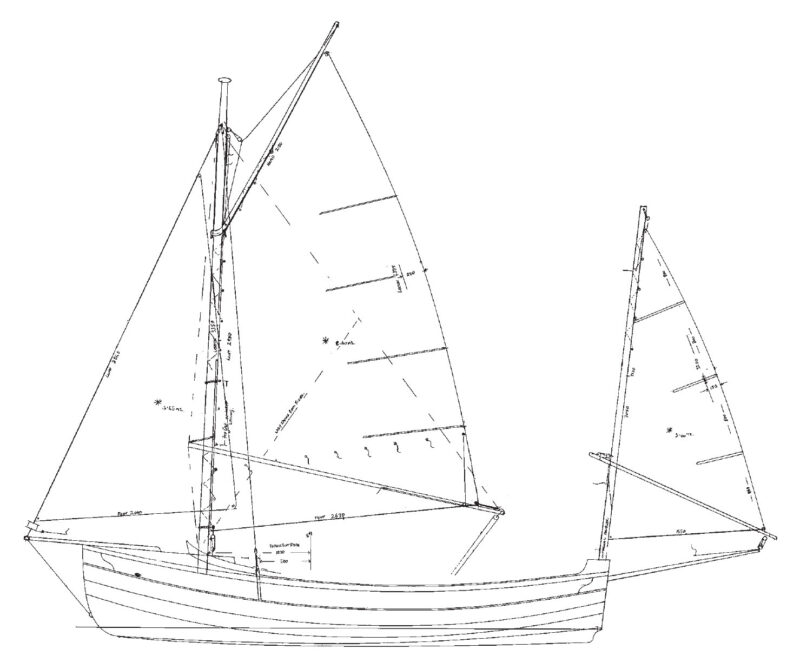

John WelsfordJohn Welsford drew the Pathfinder as a yawl—a more versatile and maneuverable rig than a sloop.

John Welsford

John WelsfordWelsford’s plans include a sloop option, for those desiring greater speed and windward ability.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.