Long before Europeans ventured to the new world, sailing dugout canoes fitted with outriggers sailed the waters in Southeast Asia and were used for migration throughout the Pacific region. The obvious seaworthiness of these boats was demonstrated by their ability to undertake remarkable voyages. Their twin-hulled form gave them stability, and the slender hulls gave them speed and seakeeping qualities that the western world could only dream of. Today, the recreational market offers many two- and three-hulled vessels for voyaging or daysailing. The Outrigger Junior is a modern adaptation of these early outriggers designed for beach sailing and fast spins around the bay.

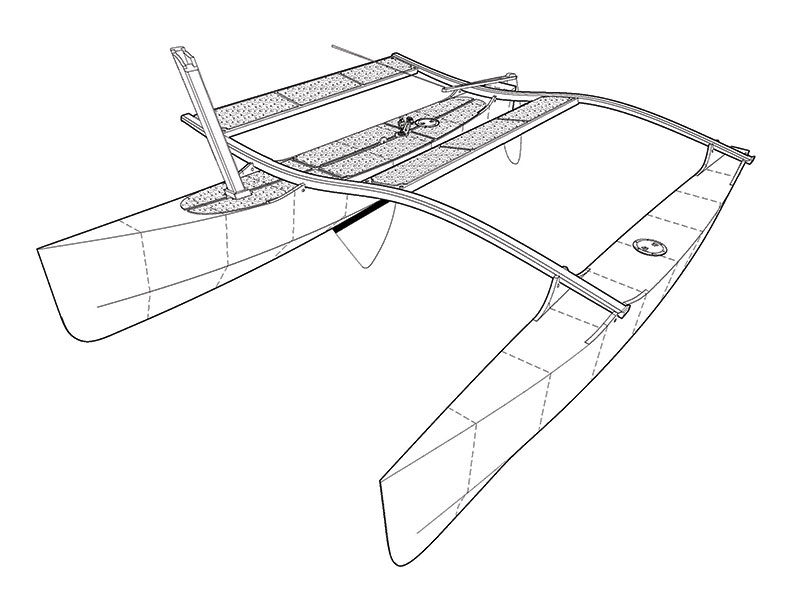

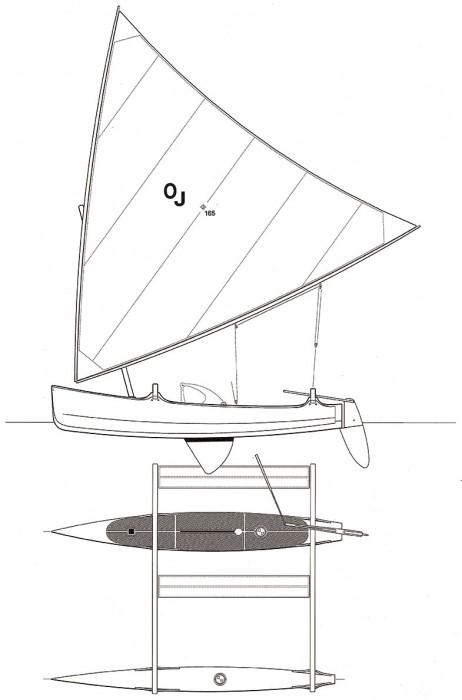

Once you step aboard this boat, you will realize that it is different. First off, it is not symmetrical. The sweeping curved akas support an outrigger hull on their port end and a cockpit seat to starboard. The outrigger side has a seat also, which is the only symmetrical arrangement in the boat. The boomed lateen rig has a stub mast, raked forward about 15 degrees. When the sail is hoisted, the yard is almost vertical and boom tilts up slightly with a large triangular sail between. The boom sweeps very low when eased out, but rises to clear the seated crew when centered. The outrigger-always-on-one-side configuration should cause a slight asymmetrical feel to the helm. But that does little to affect its sparkling performance, often sailing at close to wind speed.

Outrigger Junior is asymmetrical, with an outrigger on the port side only. The hull form, lashings, and lateen sail are all reminiscent of features used by Pacific islanders.

Outrigger Junior was designed by John Harris, who has the advantage of modern technology and materials; his company, Chesapeake Light Craft (CLC) of Annapolis, Maryland, is producing the boat in kit form. The boat has a single outrigger, and is meant for construction by the amateur builder. The hulls of the Outrigger Junior are stitched together from plywood components, not unlike later versions of the old Polynesian sailing canoes—only today we use fiberglass and epoxy, rather than woven coconut sennit and sealant putty made from tree sap.

The lateen rig has similarities to the crab-claw sails of the early boats. And like the old boats, this vessel platform, composed of hulls and crossbeams (akas), is lashed together, but now using space-age cordage. Instead of deep hulls and a steering oar, the CLC version has a modern pivoting centerboard and kick-up rudder to facilitate operating from the beach or sailing in shallow water. I would imagine that the old waterlogged dugout hulls were quite heavy and required considerable muscle to drag up the beach, whereas this new boat is very light and can be handled by a young couple.

Chesapeake Light Craft of Annapolis, Maryland, supplies kits with pre-cut parts for the boat’s stitch-and-glue hulls, which are relatively easy to build.

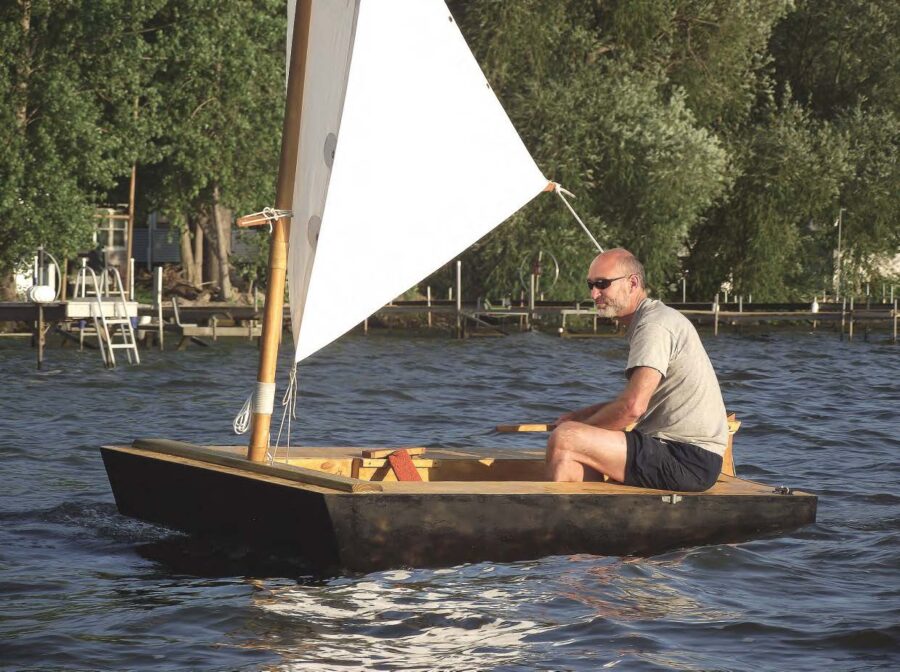

The amateur builder should have no trouble constructing this craft. As with other products of CLC, it has CNC router-cut components, and an extensive construction manual. Long plywood sheet components are spliced together with puzzle joints that fit tightly to avoid any misalignment. Bulkhead tabs fit into tight slots in the planking to assure accuracy of placement. Predrilled holes correctly position all the stitch-and-glue joints. Assembly of each hull, crossbeam, and spar is almost foolproof. Finish quality, however, is dependent on the care taken during construction and final sanding. The prototype I sailed was varnished bright, showing off the marine-quality okoume plywood.

Sailing this outrigger feels different too. There is more boat hanging out one side than the other. On either tack the boat accelerates quickly when the sail is sheeted in. The difference in helm, from one tack to the other, is hardly noticeable. The steering is good and responsive, but not as crisp as you might expect. That may be due to a thin rudder and centerboard, a concession to simplicity of construction from two layers of 9mm plywood. The flat shaped foils show a tendency to stall at lower boat speeds. Hull forms with a deep V shape continuing aft to the transom also resist turning, acting like they are on rails, which further slows the steering response. All said, however, I was able to short-tack up a narrow channel in fluky winds with amazing speed. Maybe the only thing that is really different about this boat is how fast it is.

Nylon nets laced in between the components help keep gear and people aboard.

Unlike keelboats, multihulls gain stability with weight. That weight is usually positioned between the hulls so they can share the burden and keep the boat upright. Lightweight multihulls, especially single outriggers and proas, need to carefully balance the weight of the crew for stable operation. Without sail up, or in light winds, this boat can capsize with a single person sitting on the starboard seat opposite the ama. The boat looks intuitively stable, but due to the lightweight construction, the ama does not provide as much counterweight as one might guess. This fact gave me (a clumsy 200-lb, 70-year-old man) a swim after I slipped and fell on the outboard side tacking in light winds, causing it to capsize. The boat rolled slowly over until the mast was flat in the water and remained with sails awash. I soon recovered by swimming around to put my weight on the centerboard, which slowly levered the boat upright. I climbed aboard and sailed the rest of the afternoon more cautiously. Capsize at the dock is also plausible with no one aboard and sail over the starboard side. This suggests that a small amount of ballast in the ama might improve stability. But the orthodox multihull sailor would argue that it is heresy to use any ballast.

The forward-raked mast is a novel detail resulting in a nearly vertical yard (the spar at the top edge of the sail) and an increase in the sail area. When seen from a distance, the sail plan is distinctive. The gentle arcs of the spars add to the aesthetic quality of the boat profile. It almost looks like a sliding gunter rig with a long boom. A downhaul on the boom actually prevents the boom from moving forward since the halyard attachment to the yard is well forward of the center of gravity of the combined sail, yard, and boom. When the downhaul is slacked, the sail assembly rotates and the clew end of the boom becomes lower. In practice, the downhaul is not necessary since the mainsheet pulls down on the boom, but the boom needs to keep its position with respect to the mast.

As the sail is eased out, the boom sweeps down in an arc to become almost horizontal. Because the rig is positioned rather low, the sail obscures all forward view if you are sitting to leeward. You may not have the option to sit to starboard in light winds and so your view would be obscured when the boat is on starboard tack. The addition of a large window in the sail, near the boom, would be an asset in this situation. However, the window will be stiffer than the sailcloth and will cause difficulty with furling the sail on the spars for transport. One of the benefits of having two spars (a yard at the top, boom at the bottom) is the ease of furling. Drop the sail onto the akas and roll it up starting from the middle.

The two sweeping crossbeams, called akas, and the seats, are lashed to the hulls with nylon. The boat is easily disassenbled and stacks neatly for trailering.

A family car should have no trouble towing the weight of this boat on a small trailer; larger cars or small trucks could carry it on a roof rack. Two average-strength people can lift the 84-lb main hull, which is the heaviest component. The boat gains weight quickly as it is assembled, so select a spot close to the water. The fully assembled weight of about 260 lbs will require four strong people to slide or lift into the water. Simplicity always has a trade-off, and in this case it is cost and assembly time. Each lashing does not take long, but there are lots of them. CLC is currently working on a faster lashing method. Expect to take an hour to sail away, and two-thirds of that to return onto the trailer. Lightweight, very inexpensive kit trailers will accommodate this boat. The longest component is the yard, sail, and boom package. Some contrivance may be necessary to elevate this above the towing vehicle to avoid any overhang beyond the hulls.

Sailing this boat was pure fun, providing me with the exhilaration of speed. Watching it slice through the waves is fascinating, with its smooth and level ride. The boat speaks to one’s sense of novelty and adventure. The bold sheerlines, strong out-thrust bows, and forward-raked mast, combined with a gentle curve of the yard and boom, create a purposeful image. Even as it sits on the beach, the boat looks like it wants to go somewhere. Once aboard, you can conjure up thoughts of those Pacific Islanders making adventurous passages to discover new islands in the vast ocean.![]()

John Marples is a yacht designer and marine surveyor (www.searunner.com) living in Penobscot, Maine.

Outrigger Junior Particulars

[table]

Length/15′0″

Beam/12′0″

Hull weight/260 lbs

Maximum payload/450 lbs

Sail area/165 sq ft

[/table]

Plans and kits for the Outrigger Junior are available from Chesapeake Light Craft, 1805 George Ave., Annapolis, MD 21401; 410–267–0137; www.clcboats.com.

Chris White designed a nice little tacking proa like this back in the ’80s. I believe it was to be built with Constant Camber panels. I don’t know how many were built; I was personally more interested in his Discovery 20, a daysailing trimaran, but I’ve always thought that Chris’s little proa would be a lot of fun to sail. It looks like John Harris might have felt the same.

One thing I remember Chris saying is that “symmetry ain’t all it’s cracked up to be.” There was a fast tack and a seaworthy tack. You’d have more fun on one, and do the tuning/bosunry tasks on the other!

I’ve gotten rid of my beach cats years ago, largely due to storage issues with such a large trailer. So I’ve often thought a light car toppable breakdown beach cat would be pretty great. I’ve lately been sailing my CLC open cockpit double kayak (Mill Creek 16) as a tacking outrigger, with an ama/aka I designed. It’s a blast, though not overly fast. I follow John Harris and like the cut of his jib, especially when it comes to his now handful of proa/outrigger designs. His big 31′ proa kit Madness is currently a bit of an obsession of mine, but that’s a BIG project not quite on my billet yet.

All of this said, I should be completely in love with Outrigger Jr. Yet, hmm. One – it seems kind of heavy. I have to wonder if it’s a bit overbuilt. Most proas the outrigger hull would be a lot smaller relatively – which would also save weight. I would think it would be better to sit in or on the main hull on stbd tack, rather than over the side, tempting as you say a tipover. Two hulls, yet no storage in either. And all that lashing – got to be a better way.

But she’s a beauty. Very Polynesian looking, and kudos on the lateen rig and not being wedded to the standard main and jib. Very fitting on this boat.

Reminds me of the Malibu Outrigger popular in Southern CA in the 60’s. Fun to sail launching off Malibu Beach through the surf and riding back in just behind the crest of the wave.

John Harris was well aware of the Malibu Outrigger when designing this boat, and references it in some of his writing. He is a talented designer with many years of experience designing lightweight craft, and I suspect that the dimensions are what they need to be for the intended use. I look forward to sailing this one.