Mark Kaufman—a high-school woodworking teacher and collector of vintage runabouts—spent years looking for a classic runabout design to build that would complement his antique two-cylinder Mercury outboards. He had in mind something small enough to hum along with a 10- to 20-hp outboard and with a roadster-style cockpit to accommodate two. Kaufman knew that runabouts with hard chines could get tripped up during tight maneuvering and throw their pilots, so he wanted a boat with beveled—or “anti-trip”—chines. He found such a design while perusing a 1938 issue of Motor Boating magazine, which featured plans and building instruction for a boat designed by Bruce N. Crandall. The article, “Flyer—A Midget Runabout,” written by Crandall’s brother, Willard, stressed the 10′ Midget’s ease of construction, overall lightness, low cost, and ability to plane when powered by a 5- to 10-hp outboard.

Some 82 years later, these same attributes appealed to Kaufman, who opted to power his Midget with a 1950 Mercury KG7 Super 10 Hurricane—“the hotrod of the day,” he noted. “It’s a ball of fire.” In practice, the KG7 performs more like a 16- to 18-hp, which bumps up against Crandall’s maximum power recommendation of a 16 hp.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenThe outboard is equipped with a yoke for steering. The arrangement of the steering cable and pulleys adds to the wheel’s mechanical advantage for a light touch with firm control. The plans called for spartan accommodations in the cockpit: just a plywood backrest and the floorboards for a seat. The cushions are a wise addition.

Crandall (1904–82), a naval architect, designed single-step hydroplanes, runabouts, utility boats, and sailboats. Many of his designs were published in Motor Boating, Sports Afield, Popular Science, and other magazines. During the late 1920s and early ’30s, he also co-owned—along with Willard and their father, Bruce V. Crandall—the Crandall Boat Co., where they designed and manufactured watercraft and sold plans for the do-it-yourself market. He continued designing boats until his death at age 77.

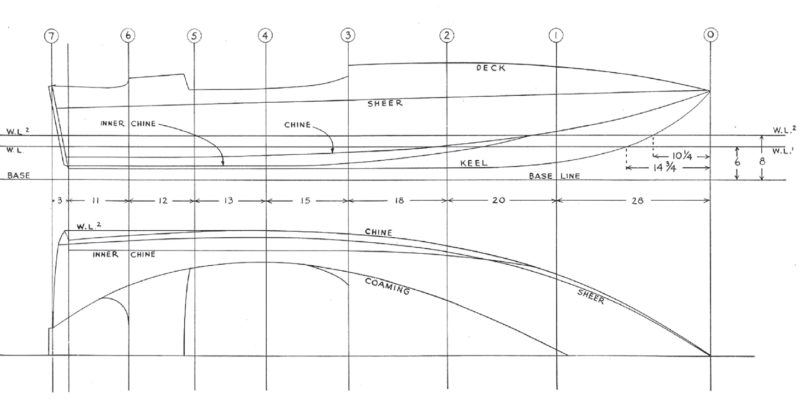

The Midget was a recreational version of Crandall’s 13′ Flyer—a class C racing runabout that also had beveled chines, as did many of Crandall’s designs even though they were uncommon at the time. The Midget is not believed to have been commercially produced. Kaufman obtained plans for the Midget Flyer from D.N. Goodchild, whose company sells reprints of the original 1938 plans.

Kaufman, who has taught high-school students how to build boats for more than 20 years and for a decade also was an instructor at WoodenBoat School in Brooklin, Maine, wanted to build his Midget Flyer using traditional lightweight batten-seam construction without any plywood, fiberglass, or epoxy. Solid wood planking would be screw-fastened to battens, which, in turn, would be fastened to internal frames.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenThe boat’s controls are simple: a 14″ custom-built wheel, a deadman’s throttle, a tachometer, and a kill switch. The white fire extinguisher is close at hand just forward of the throttle.

Crandall specified mahogany, cedar, cypress, spruce, and white oak for planking, frames, transom, and battens. Kaufman opted for local hardwoods—sassafras, white oak, and paulownia—and held the cost of his wood down to $650 while keeping his Midget light in weight without sacrificing strength, durability, or decay resistance. He built the Midget in the woodshop where he teaches; the project took 18 months of his spare time.

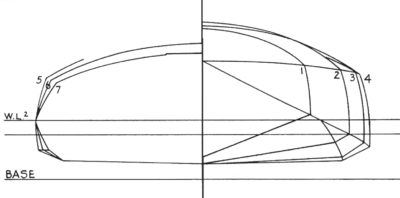

Construction begins upside-down on a strongback with sawn ring frames constructed of lapped pieces for the bottom, sides, and deckbeams. The plans specified frames made from 5/8”-thick spruce or mahogany or 1/2″-thick white oak, but Kaufman went with sassafras, making the frames 9/16″ thick and the transom 5/8″ thick. Crandall had specified a transom rake of 12 degrees, but Kaufman, after determining that 15 degrees would provide a better angle for the outboard, added a motor block beveled to 3 degrees.

The keel is 3/4″ x 1-1/4″ white oak. The plans also call for 3/4″ x 1″ white oak for the full-length chines and 3/4″ x 1-1/4″ spruce or mahogany for the inner chines, which are faired with the chines just forward of station 2 and together create the angled anti-trip facet; he used 3/4″ x 1 1/4″ white oak for both. Kaufman originally used sassafras for the 1/2″ x 1-3/4″ battens, but it didn’t yield a smooth fair curve when steamed. He then tried paulownia, an exceedingly light Southeast Asian hardwood that now grows in Pennsylvania, which worked beautifully, and weighed less than half as much as white oak.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie Mullen“Auxiliary power” is provided by a paddle, used mostly for maneuvering around a launch ramp or a dock. The diminutive Midget Flyer offers good stability even while standing in the cockpit.

Kaufman also used paulownia for hull planks, taking advantage of the wood’s lightness to make them 7/16″ thick instead of the specified 5/16″ mahogany, cedar, cypress, or spruce. In a rare departure from traditional materials, he used 3M 5200 bedding compound to seal the plank seams. (The plans specify that seams below the waterline be filled with strips of cotton “flannelette” saturated in marine glue.)

Once the hull is right-side up, the cockpit coaming and transom knee are installed before the final two upper side planks are beveled and attached. The afterdeck is composed of six wide planks and a pair of narrow outer planks that run from the transom to station 3. Crandall called for the foredeck to be covered in light cotton cloth or balloon silk, tightened and sealed with airplane dope. Following the interior and exterior finish work, Kaufman used 2.7-oz aircraft Dacron, which he heat-treated and sealed with Randolph non-tautening nitrite clear dope.

Crandall’s article doesn’t mention the steering wheel, so Kaufman made a beautiful 14″-diameter one of brass and sassafras. He chose to mount the wheel amidships to maintain an even keel when driving solo.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenHere, builder Mark Kaufman sits amidships as he takes the helm solo. He’ll slide to port to bring a passenger along. The plans called for the wheel to be set to port, which works fine for boating with two, but awkward and unbalanced for going alone.

Kaufman used leftover planking stock for the floorboards and backrest, and he used the same wood for a seat, although no seat was mentioned or drawn by Crandall. The plans specify 1/4″ plywood for the backrest. For his backrest and seat, Kaufman fastened paulownia planks on sassafras cleats.

Crandall suggested installing 1/2″ aluminum half-round gunwales; Kaufman went with white oak 3/4″-thick tapered spray rails and 1/2″ x 7/8″ rubrails. The original plans also called for an aluminum fin for boaters wishing to travel over 20 mph, but for ease of trailering and to permit the Midget to be hauled ashore, Kaufman opted for a 3/4″ x 1 1/8″ white oak shoe keel that ends 18″ shy of the transom.

To get deck fittings with the classic look he desired, Kaufman fabricated his own. Instructions on how he made them are featured in his article, “Fillet Brazing for Custom Boat Hardware.”

Kaufman’s Midget Flyer weighs 130 lbs, just over Crandall’s estimate of 125 lbs. Kaufman chose a trailer with a center roller forward to support the forefoot of the keel. The Midget trailers, launches, and recovers “effortlessly,” according to Kaufman, who usually does this job by himself.

Alison Langley

Alison LangleyA solo skipper can hit a top speed of 34 mph, a good clip made all the more exciting by the proximity to the water and rush of air over the bow.

When I piloted the Midget, I found that at low speed its trim is close to level; the bow rides up slightly, but not in an unsightly manner. With a touch of the throttle, it leapt to life and snapped on plane without delay. I thoroughly enjoyed the proximity to the water while piloting the Midget, an intimacy that reminded me of paddling. Kaufman said that his GPS clocked the Midget’s top speed at 34 mph with a solo driver. I piloted the boat in a few inches of chop and was at a speed of about 25–30 mph when I became aware of a transition from light chatter to pure glide; the hull felt as though it was floating, and the ride turned surprisingly smooth. “The best performance is in 3″ of chop,” Kaufman says, “you’re getting air under the boat.”

Several years back, I piloted a three-point hydroplane and never got comfortable with its airplane-like speed. In contrast, the Midget Flyer offers comfort and speed that do not disappoint but remain closer to the recreational side of the performance scale. You won’t lose your shirt, though your hat might blow off. The Midget doesn’t have a windshield, so be prepared to feel the wind.

“You’d kill the experience if you put on a windshield,” Kaufman told me (though he adds the caveat that the curvature of the deck pushes a fair bit of the airflow overhead). The wind and the proximity to the water combine to enliven the Midget’s ride, yet I felt at ease behind the wheel after a few preliminary runs.

The beveled chines and keel shoe stabilize turns and engender a sense of confidence—the Midget carves gracefully. The experienced driver will find that the Midget can remain on plane through playful banking maneuvers, though even Kaufman backs off the throttle for sharper turns, and high-speed turning requires a larger radius. In waves of 1′ or more or when crossing larger wakes, the Midget may porpoise as its shallow-V hull skims across the waves more than it cuts through them, but backing down the throttle will quickly return the pilot to comfort.

Alison Langley

Alison LangleyThe Flyer maintains level trim at almost any speed. The bow rises slightly as the boat jumps up on plane, but comes back down quickly. The deck is an unusual combination of planks aft and fabric forward.

Under rough conditions, Kaufman has also found that turning slightly and planting more of the hull’s forward V as well as one of the chines into the water can help stabilize the hull. Even in turbulent waters, the Midget offers a dry ride. Kaufman has only been doused once, when he was out on Long Lake, near Naples, Maine, in 2′ waves and even then, it was just the spray blowing off the crests. He also once went from full speed to a dead stop—he ran out of gas—and no water sloshed over the transom. For general use, he keeps trim ballast in the form of a gallon jug of water lodged under the foredeck centered near the bow, which helps to minimize porpoising. For high speeds, the bow ballast comes out and the cavitation plate on the outboard is placed parallel to the boat’s bottom. For routine use, the engine is tucked in about 2 degrees toward the transom.

The plans don’t call for any flotation, though Kaufman often carries a few boat cushions beneath the foredeck. Knowing that he would regularly fish from his Midget, he added a pair of vertical braces under the afterdeck to support its use as a seat.

While the cockpit was designed to accommodate two adults, the quarters are a bit tight when riding with a partner, and the driver will have to handle the centered wheel while sitting to the side. Getting on plane can require both to lean forward. Even so, the thrill of the ride sweeps away any inconveniences. With two aboard, the Midget’s top speed is 29 mph.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenAn outboard rated around 16 hp is all that’s needed to get the the Midget Flyer moving at an exhilarating speed.

For Kaufman, the Midget “is as fun as it gets. I’ve got three powerboats, but with the Midget the fun factor is high and the hassle factor low.”![]()

Donnie Mullen is a writer and photographer who lives in Camden, Maine, with his wife Erin and their three children.

He wrote about paddling the entire length of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail in our February 2016 issue. His article “Investing in Memories: Canoe Camping in Northern Maine,” appeared in our September 2015 issue and he reviewed the Original Bug Shirt in our August 2015 issue.

Mark Kaufman wrote detailed instructions for building the Midget Flyer in WoodenBoat magazine, Nos. 275, 276, and 277.

Midget Flyer Particulars

[table]

Length/10′

Beam/45.5″

Beam of planing surface/38″

Maximum power/16 hp

Weight/125 lbs

Capacity/2 persons

[/table]

Plans for the Midget Flyer are available from D.N. Goodchild, who reprinted the article that originally appeared in the January 1938 edition of Motor Boating. Goodchild identifies the article as publication No. 5381, “A 10-ft. Midget Runabout”; see www.dngoodchild.com or phone 610–937–169.

Update: 8/13/21 D. N. Goodchild has had trouble with his website and is currently working to get it up and running.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Very nice build. If a 5-hp Torqeedo electric motor were used, any guess on what speed it would get to?

Thank you, it has been a lot of fun. I haven’t had any experience with these electric motors, but I had tried my 6-horsepower Mercury Mark 6A on the boat and, if I remember correctly, it got to 16 mph GPS. I would guess that the speed would be approximately the same with the 5-horsepower Torqeedo.

I built one of these boats, would not turn without a skeg or fin at all. Extremely dangerous.

If you use 1930 plans you will get 1930 performance. Just under power it and it will be OK.

Add skeg. I know what this involves, I have built boats, but it won’t take too long. It’s actually not that deep.

Wonder how it would trim with a modern 4 stroke which are a good bit heavier than the equivalent two stroke? How much does the Merc weigh? The Torqeedo is only nominally a 5 hp motor, but only 35 or so pounds. Common around dinghy docks with inflatables; not obtaining impressive speeds.

The Mercury KG7 weighs 65 pounds, plus approximately 12 pounds for the two gallons of fuel in the integrated fuel tank. The total weight with a full fuel tank is approximately 77 pounds. The remote fuel tank on other engines could be located forward of the cockpit area to help offset the weight of heavier engines. I have not tried any of the newer four-stroke engines on the boat.

While in High School (we won’t say how long ago that was), I built a MiniMax from Motor Boating magazine plans. It would fly with a 15-hp Merc with me and my girlfriend aboard. Flipped it once crossing a pontoon boat’s wake. Thank goodness for the “air pocket” front-end flotation chamber. Great magazine. I wish that I had kept all of those old issues.

I wonder if I would be too tall and heavy for that boat. I’m 6’6” and 250 pounds.

The boat performs well with two 170-lb passengers. I’m 5’11” and weigh 170 lbs, the heaviest passenger that I’ve taken for a ride weighed 225 lbs. The boat handled the weight fine once it was up on plane. However; to get it on plane, I had to lean out over the front deck. It will handle your height and weight as a single-seat boat or with you and a small, lightweight passenger.

I thought that you might like to see my version of an old classic by Bob Switzer. Happy Boating.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozsALBE1-cg&feature=youtu.be

Mark Kaufman,

Your construction of Midget Flyer 10’ was perfect. Congratulations! I want to build a 10′ Midget Flyer and detail the project with the small changes you made.

Thank you

Thank you, Orlando. I’m sure that you’ll enjoy both building and using the Midget Flyer!

I tried to contact the source for the boat plans but I couldn’t access the website.

Thanks for the heads up. I tried the Goodchild website and had trouble getting past the home page. I’ve emailed D.N. Goodchild to see if access can be restored.

In the meantime, you can get to the original article in the online version of Motor Boating magazine. The article is on page 178.

—Ed.

A nice build story and presentation of the outcome. Much to be said for those small boats that “have a high fun factor and little hassle.”

Two questions: could this boat be lengthened an inch or so at each frame? Have you seen a stitch-and-glue version of this design?

Thanks

If I was lengthening the boat a small amount, I would increase the spacing of the frames by a certain percentage to acquire the desired overall length. Since the frame spacing varies at 11-12-13-15-18-20 and 28 inches, if they were each extended by an inch there could be fairing problems.

I am not aware of a stitch-and-glue version.

Hi Mark,

My name is John and I’m from Annapolis, MD. I’m desperately trying to get a set of plans for this boat. I have one that belongs to a family friend built in 1938/39 that requires a keel up restoration. The source mentioned in the article has been unresponsive, I believe he’s having health issues. Are you able to help point me in the right direction?

Like what I see. I have a small hydroplane that needs some work, also a Mercury Hurricane. Haven’t used it for many years. Last time it was used was when the starter rope tore. Been sitting in the garage ever since.

Later,

Walter Stanz

Milwaukee, Wisconsin