HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNER

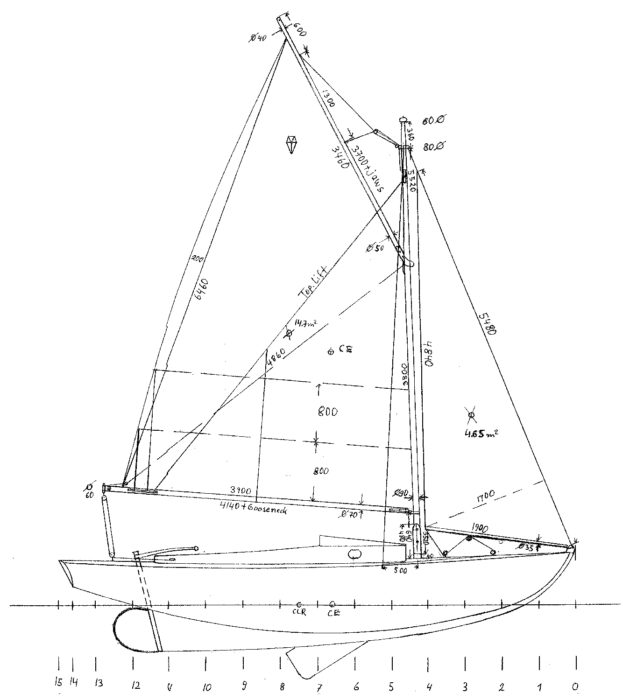

HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNERTo develop his trailerable daysailer, Herbert Krumm-Gartner started by carving a half model, inspired by the boatbuilding methods and design aesthetics of Nathanael Greene Herreshoff.

JADE took shape the old-fashioned way: a spokeshave and a piece of golden New Zealand kauri timber. Boat designer and builder Herbert Krumm-Gartner is German by birth and has lived in New Zealand for 26 years, but as the half model gradually emerged from the kauri, it reflected the lines of a classic American daysailer.

A year later, in September 2012, the full-sized, 23′ version was afloat—the first boat of Krumm-Gartner’s Gem-class design with a piece of New Zealand jade or greenstone, pounamu in Maori, on her tiller. Krumm-Gartner named the class Gem because his wife, Romy Gartner, has a past life as a jeweler and because, he says, all classic boats are like gems.

She sparkles with beauty from her spoon bow in a gentle sweep through her low profile to the counter stern that finishes in a gleaming mahogany transom, topped by the glossy Douglas-fir spars of her gaff rig. From the beginning, Krumm-Gartner says, “It was the aesthetics that drove the design.”

Like many before him, Krumm-Gartner is inspired by Nat Herreshoff’s designs—a connection that began in the 1980s when Krumm-Gartner was an apprentice boatbuilder in southern Germany. He was frustrated at the lack of interest in building wooden boats. For his apprenticeship project, he wanted to build a round-bilged clinker boat (also known as lapstrake), but his boss insisted he build a boat with a flat bottom. “But I had to build it his way, the right way up,” Krumm-Gartner says. “I now mostly build upside-down, but you couldn’t argue with your boss.”

He found salvation in a local bookshop, which stocked books on boatbuilding—nearly all of them in English. Today, Krumm-Gartner’s German accent has disappeared, but in the 1980s his English was schoolboy standard. He bought Building the Herreshoff Dinghy, published by Mystic Seaport, and translated key phrases into German so he could understand the building process. He still has the book, including his penciled notes in German. In the same shop he saw his first WoodenBoat magazine. “I’ve been a subscriber ever since,” he says.

The more Krumm-Gartner talked about wooden boats, the more he heard about New Zealand. He knew a tradesman in Germany who knew someone in New Zealand who knew boatbuilder John Gladden. Many international phone calls later, Krumm-Gartner moved to New Zealand with Romy to work for Gladden. “He was great,” Krumm-Gartner says. “He took a lot of time to explain something and drew diagrams of what he wanted. I did some quite complex stuff, like building a gamefish launch. It was like a second apprenticeship.”

Krumm-Gartner later set up Classic Boats Ltd. He has built new boats and has restored many classic yachts, but he held a dream to build a boat to his own design.

In 1999 he designed a Herreshoff-inspired 16-footer, but he and Romy felt it would be too small. “I didn’t want to get wet,” Romy says. Instead, they bought a small classic yacht, which they kept on a mooring, but were disappointed by her obvious need of care when they returned from a three-month trip to Germany.

“It made me realize I wanted a trailer boat at home to minimize pre-Christmas maintenance,” Krumm-Gartner says. “In the United States, daysailers are making a comeback, and they are in New Zealand too. They have lots of varnished wood, but you don’t have to be afraid of it because you can protect it at home under cover.”

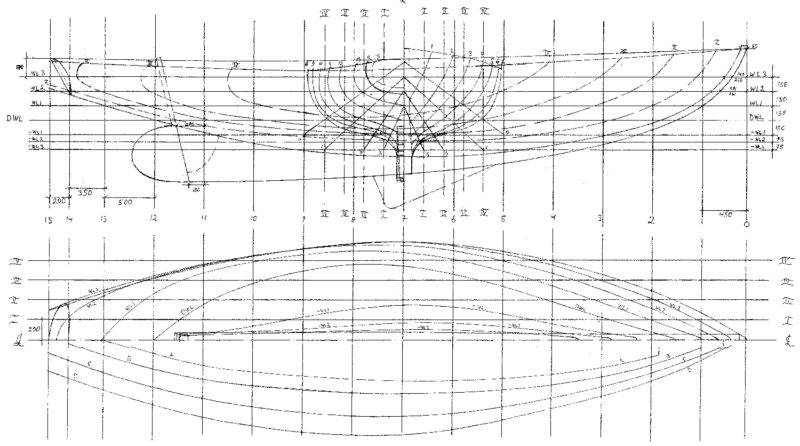

“Looking for a challenge,” he revisited the 16-footer, stretched it to 23′, and added more freeboard. “I designed it the Herreshoff way,” Krumm-Gartner says. “I did a half model and shaped it until I liked what I saw.” His book about the Herreshoff dinghy was a close companion.

HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNER

HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNERLike Herreshoff yachts, JADE, the first of the Gem class boats, was built upside-down with one mold per laminated frame. For watertight integrity and structural strength, the laid deck’s sprung planks were installed over a plywood substrate.

The aesthetics brought the challenge. “It’s difficult to build a counter stern and a curved transom. It was also very difficult to plank, and I didn’t know how difficult when I designed it. The stern has a lot of tumblehome and the bow has a lot of flare, so they are very complex curves and a plank needs some convincing to take that shape.”

The construction wood was mostly kahikatea, known as New Zealand white pine, which had been salvaged from submerged logs. The key in bending the planking was to use narrow widths. “I put a straight edge on one side of the plank and then I put a fair curve into the other one, so that amidships the planks could be 70 to 90 mm [23⁄4″ to 31⁄2″] wide, tapering out to about 40 mm [about 11⁄2″] at the ends; then I stuck them in the steambox. We wrapped them around and bent them around the building mold.

“Usually when you steam planks you’re bending them one way, but we bent these around the boat and edge-set them up or down, so we had to keep them narrow. This method wastes less timber than if cutting carvel planks the conventional way from wide boards,” he says.

Krumm-Gartner’s favorite tools were planking clamps that he had first seen in WoodenBoat magazine and ordered from the United States. “They attach to the rib,” he says. “You can then wind down the plank so you get this super-tight fit. Normally you’d have to do with a normal clamp and wedges. Every rib was laminated over a frame so the building jig could be re-used, as Herreshoff used to do.”

The edge-glued planks are covered in one layer of 6-oz fiberglass cloth set in epoxy. It’s a good method for a trailering boat that will be out of the water most of the time.

Krumm-Gartner says JADE is helping to preserve traditional boatbuilding methods. “Building is the only way you can acquire a skill properly,” he says. “If you repair a boat and you replace a plank, you’re not a proficient planker. But if you build 40 planks, select the planks, steam them, you really learn the process. The first plank took me most of the day to get it on. Later, we did a pair a day.”

Krumm-Gartner and Romy built JADE together; for Romy it was an unofficial apprenticeship, albeit without plans. “Herbert would say, ‘We’re doing this.’ And I’d say, ‘Show me,’” Romy says. “It was all in his head, so I couldn’t picture it.”

“Plans can be limiting,” her husband says.

They recorded every part of the construction, from lofting through to final fittings, in a diary, including photographs, with suggestions for improvements and a record of the hours for each job.

Krumm-Gartner selected 23′ as the length so the boat would be easy to trailer, store, sail, and maintain yet still achieve a reasonable turn of speed. The cabin sleeps two comfortably and the cockpit seats four people. Facilities include a chemical toilet under the cabin sole, an icebox under the port cockpit seat, and a stove to starboard. There are watertight bulkheads in the bow and lazarette. Four sockets around the cockpit accept stanchions to support a sun tent.

When it came to motive power, Krumm-Gartner didn’t want an outboard on a bracket. “They are ugly, unwieldy to use, and ineffective in a choppy sea,” he says. But he didn’t want an inboard engine either: “It would have dominated the cockpit, cost more, and weighed more.”

After playing around with an outboard-shaped piece of plywood in the workshop, he permanently installed an 8-hp Yamaha outboard in a well in the aft cockpit. It pushes the boat at 6 knots and is angled at 12 degrees so that the propeller wash streams over the rudder. A pipe in the outboard’s idling outlet takes exhaust fumes away from the outboard well. Two fairing pieces around the outboard leg also help to keep the fumes out of the cockpit.

HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNER

HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNERJADE’s commodious cockpit, with macrocarpa coamings at a comfortable height for seating, has room for four and an outboard set in a well.

JADE may have been complicated to build, but as a baby classic she is easy to sail. One person hoists gaff mainsail by pulling simultaneously on the peak and throat halyards, which are led to the starboard side of the forward end of the cockpit. The 5-square-meter [54 sq ft] jib hoists on a halyard to port. The jib’s boom makes it self-tacking, and to save crew having to lean out into the spray to trim, the jibsheets lead inside the cockpit via bronze sheave boxes let into the macrocarpa coamings.

The mainsail hoists on mast hoops made of stainless steel sheathed in leather, and thanks to an endless mainsheet it can be trimmed from either side of the cockpit. Because the boat has no bowsprit, sail handling is easy, but with no winches for trimming or hoisting sail, the crew needs to practice belaying skills.

Her stiff manner under sail befits her gentle, classic temperament. Krumm-Gartner and Romy enjoyed many sails on JADE before finally dipping the rail under, in a wind of more than 20 knots. The 15-square-meter [161 sq ft] gaff mainsail provides most of the power, unlike a modern marconi rig, for which a large genoa is usually the driving force. When working to weather, Krumm-Gartner reefs the mainsail at 15 to 18 knots. The main and jib are made of cream-colored sailcloth as a nod to the classic sailing of yesteryear.

The helm has a feel of yesteryear too, being placid but firm. It’s easy for one person to manage the tiller and sheets. Going forward on the narrow coach roof without lifelines feels strange to sailors more used to modern designs, but there’s something wonderfully snug about the varnished cockpit surrounded in sweeping coamings. The water is just inches away, and Krumm-Gartner has certainly created the feel of old-style sailing.

HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNER

HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNERShowing her early-20thcentury American influence, the gaff-headed sloop has a self-tending jib that makes sail handling simple. Low draft enabled by her centerboard makes her readily trailerable, and with her planking sheathed in fiberglass cloth set in epoxy she can be launched dry without needing time for the planking to swell.

JADE has just under 300 kg (661 lbs) of ballast for her 1.1 tons (2,425 lbs) weight, including 135 kg (298 lbs) of lead either side of the keelson and 30 kg (66 lbs) of lead in the centerboard. The centerboard brings the draft to 5′. By use of the only winch on board, the centerboard swings up into a low-profile trunk in the cockpit for trailering or creeping into shallow water when gunkholing. The centerboard winch is bronze, as are other metal fittings on board JADE, for which Krumm-Gartner made wooden molds, accounting for shrinkage.

It takes one person 30 minutes to rig or derig JADE. The mainmast, being a gaff rig, is only 6m [about 20′] and light enough for one person to manage. To lower the mast for trailering, Krumm-Gartner releases the forestay; the mast stays in its tabernacle and the shrouds stay connected. The lowered mast rests in crutches on the deck. The 4.2m [13’9″] Douglas-fir boom, gaff, and mainsail stow in the saloon. Krumm-Gartner launches JADE using an extension bar on the trailer.

JADE already has a sistership, commissioned as an open daysailer without a cabin and resplendent in varnished mahogany topsides for which Krumm-Gartner meticulously selected every plank. He and Romy built the boat for an American superyacht on which it resides in a special cradle alongside a classic runabout—a stable-mate that Nat Herreshoff would surely appreciate.![]()

HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNER

HERBERT KRUMM-GARTNERJADE

Particulars

LOA 23′

Beam 6′ 6″

Draft, centerboard up 2′ 2″ centerboard down 5′

Weight 2,425 lbs

Setting the outboard motor through the keel ahead of your rudder is great idea, not showing how this was done becomes a head scratcher. Steering with just the rudder would make doing this worthwhile. Having room to allow your centerboard to clear and not compromising the keel strength had to take engineering challenge. This would have been done on the fly, would like to have seen drawings showing how you did this. Or photos would have done the same.

I agree a more in-depth discussion of the outboard well etc. would be must welcome. Also a bit more information on the decking system would have been nice. Full discloser: I am in the early stages of rescuing a very old wooden 32’ sharpie ketch that has an outboard well. I am considering a laid sprung deck. So any insights will help.

Saw her at an early launching at Hobsonville Marina. Pretty little thing!

Lovely little boat.