Envision a frustrated prehistoric man gazing beyond the crashing surf to schools of fish erupting on the surface, well out of reach: “If only I could get to them.” Every surf-casting fisherman can relate. Skiffs provide the shore-bound fisherman a new universe of opportunity, but those who launch directly from the beach when favorable conditions allow, must hope surf conditions don’t worsen before it’s time to return to land. Every continent has a stretch of turbulent coastline on the receiving end of an ocean reach spanning thousands of miles. Much of North America’s Pacific coastline fits this bill with exposed shorelines and frequent big swells.

For the early Euro-American pioneers of Oregon’s north coast, the Pacific swell was certainly a few notches more dangerous than the inshore waters of New England, where many dory designs evolved. Unlike the countless bays, estuaries, and sheltered harbors of New England, this stretch of the coastline offered no safe passages to the ocean. Pacific City, a hamlet on this stretch of the Oregon coast, was built near the mouth of the Nestucca—a coastal river with a nightmarish bar. As a result, fishermen had to choose the beach as the port of entry for their modest fleet.

Local builders started with the classic double-ender surf-dory designs of New England, but soon made longer and beamier versions for more stability among the larger swells. By the 1950s, motorwells were common in double-enders, and by the ’70s square-sterned powered semi-dories took over. Abundant old-growth Douglas-fir provided premium framing lumber, and the golden age of AA marine-grade fir plywood offered outstanding planking. Builders abounded in western Oregon, where the Pacific City Dory probably held the title as the most abundant plywood-on-frame working skiff in America. These boats were simple to build and had a length of 20′ to 22′, a beam of 7.5′ to 8′ carried well forward, a 5′- to 6′-wide flat bottom, a transom raked at 12 degrees, and sides angled of at least 25 degrees.

Sandy Weedman, (pcphotolady.webs.com)

Sandy Weedman, (pcphotolady.webs.com)With a flat bottom that’s 5′ wide for much of its length, the Hunky Dory is quick to get on plane even at low speeds. For the author’s boat, equipped with a 90-hp outboard, the top speed is 34 knots.

A beach-launched skiff should have a flat bottom and a wide, proud bow, with rocker to rise over waves, not bury into them. The framing must be strong enough to withstand the head-on wave impacts and the stinging slams as the boat falls into the troughs at the back of a wave. Returning to shore, a high transom and splash well fend off following waves while the upturned bottom at the bow resists the bow steering that can lead to a broach. Landing can be more technical than launching. The skipper needs to feather the throttle to stay in the trough between wave crests and then, at just the right moment, accelerate over the collapsing wave and onto the sand, far enough to avoid being sucked back into the break.

Sandy Weedman (pcphotolady.webs.com)

Sandy Weedman (pcphotolady.webs.com)With careful attention to the throttle, the Hunky Dory can match speed with the waves and approach the beach on the back of a collapsing wave.

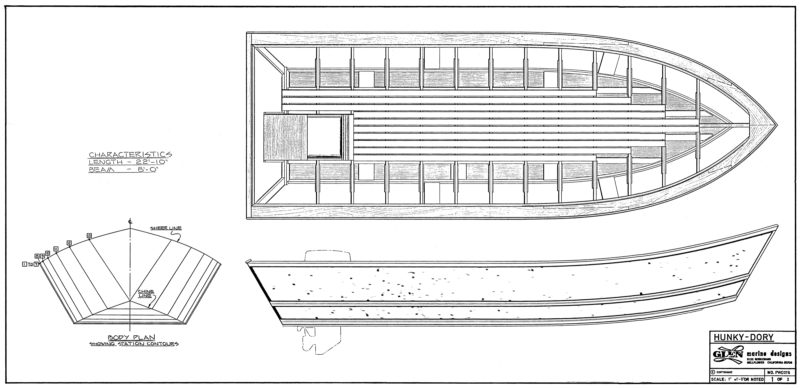

The Glen-L 22′10″ Hunky Dory (and 18′3″ Little Hunk) are the only readily available sets of plans with true Pacific City Dory DNA—not only in their proportions, but in the finer details of framing. While many Glen-L designs may well be original, many are riffs on older, established designs, as Glen L. Witt often converted known hull shapes to a more approachable plywood-on-frame construction for the home builder. We do not know what specific Oregon dory or builder he pulled lines from, but his Hunky Dory and Little Hunk carry the likeness of many 50-plus-year-old, locally designed and built dories that still launch and land on the Pacific City beach. His Glen-L semi-dories include very strong framing with heavily gusseted frame joints with numerous 1×3 inner bottom battens. The battens are not let into the frames so bilgewater can flow freely through the gaps.

The broad appeal of this design is likely its versatility and simplicity of build, not its surf origins. Its beam-forward design and wide, flat bottom make it a very stable platform as a fishing or dive boat. While the semi-dory is a proven seaworthy craft with a large load capacity, its flat bottom and reserve buoyancy make it a capable shallow-water vessel.

Sandy Weedman (pcphotolady.webs.com)

Sandy Weedman (pcphotolady.webs.com)With its broad flat bottom, the Hunky Dory can slide over thin water—even as the outboard is kicking up—before coming to a stop on the sand. Note how well the spray rail turns the water away.

In 2019, I purchased plans for the Hunky Dory and salvaged some old Douglas-fir lumber, including four sheets of 1970s-era AA Douglas-fir factory-scarfed 20′ plywood. The package from Glen-L came with a set of study plans, a build guide, and full-sized patterns for the frames, transom, stem, and breasthook. The patterns have copious annotations and identify the cuts in the frames for the sheer clamps and chines on each frame station. The patterns also clearly show the elevation of each frame on the jig needed to produce the straight bottom aft and the upward curved bottom forward. The build jig, typical of Glen-L designs, is a double beam that works well to stabilize the awkward heft of the transom and 12 frames, making subsequent adjustments and alignments much easier. The spacing between these elements can be adjusted proportionately to lengthen or shorten the dory up to 3′. Once the frames, transom, and stem are fabricated and mounted on the jig, the rest of the build is an intuitive process of marking, cutting, and fastening longitudinals. While I had some 20’ sheets of plywood to work with, the drawings detail butt joints with 8″-wide butt blocks or scarfed joints.

The plans offer alternatives for a motorwell or transom-mounted outboard, although they don’t provide details on a splash well for the transom version. Spray rails are shown in the drawings, but their shape and placement are left up to the builder. I set mine at a roughly 8-degree angle from horizontal down from the bow to the stern and applied curved fillets on the undersides to turn the water away from the hull. The interior is similarly left to the imagination of the builder, which is typical of many similar open boats. I opted for a plywood stand-up center console with a raised cooler as a leaning post. An optional set of plans detail five different cabins that can be added during construction or retrofitted later.

While some may gravitate to the motorwell option, the transom option is a more efficient planing surface, is just as safe with a good splash well, and provides more cockpit space for fishing. All contemporary Pacific City Dory builders have opted not to build the motorwell.

In a departure from the Pacific City style, Glen-L added four 1×3 battens to the outside of the bottom. They are an absolute no-go for beach landing because they violently grab the sand, so I installed them on the inside of the bottom to keep the strength they provide, while leaving the bottom smooth. Instead of the single layer of 1/2″ plywood specified for the bottom, I used two layers of 3/8″.

Rachel Bruce

Rachel BruceThe plans call for battens on the outside of the bottom, but for landings on a smooth sandy beach, they would only dig in and stop the boat before it could slide well up the flats. With the boat safe from the waves, it can be picked up by a trailer with a tilting bed and a strong winch.

To resist cracking from hard bottom hits, I reinforced the bottom piece of each frame with plywood cheeks or gussets, epoxied and nailed on either side. Due to the forces involved in surf launching and landing, I wanted to increase the strength of the transom and added two large transom knees on the bottom and quarter knees on the sides.

Although most Pacific City dories have an arrow-straight sheer aft of the upswept bow, I grew up in New England, and my idea of a sheerline is a sweeping curve. Whether a lobsterboat, dory, sloop, or a simple skiff, a nice curve from bow to stern was essential, so I gave my Hunky Dory just enough sheer to please my eye. Because the sides in that area are straight and set at a 30-degree angle, lowering the middle of the straight sheer to achieve the curve I liked also decreased the beam slightly, giving the boat a very subtle hourglass shape when sighted along the sheerline.

I started this build in December 2019, worked at a fairly fast clip, and finished by June of 2020 having logged about 375 hours. When the hull was complete, I turned my attention to the motor and trailer. Despite Evinrude closing its doors that year, the company’s E-tec 90-hp was a perfect choice with responsive two-stroke power for the surf zone and excellent fuel efficiency. I had an E-tec dealer install the motor. I salvaged a tilt-trailer from a junked dory and after some modifications to fit the dory, I was ready for a late-summer launch.

To say that launching and landing the Hunky Dory in the surf requires a steep learning curve would be an understatement. Over the course of the first couple of seasons, I gained experience and appreciation for the Hunky Dory’s seaworthiness. I was amazed how the boat ate 6′ curling waves on launch, often without even a splash of water over the bow, and thrived out in the open ocean in big rolling swells.

The boat jumps to a plane almost instantly and stays on plane even running as slow as 5 to 8 knots (some might say this relatively light hull with a large flat bottom is always on plane). It did require some trimming by moving the batteries from the stern to the center console; keeping crab traps and extra gas tanks forward also helps. The dory surprised me by how it carved turns and resisted skidding, an effect, perhaps, of the crisp, straight chines.

The dory’s wide, flat bottom helped make the E-tec exceptionally fuel efficient. On a 90-plus-mile round trip to albacore fishing grounds, the engine only drank about 17.5 gallons. All flat-bottomed boats pound in certain conditions, so for folks who want to spend lots of time running above 20 knots in rough, choppy seas, the Hunky Dory is probably not the right boat for them. But at around 15 to 17 knots this skiff moves comfortably in moderate seas, and in flat seas it can easily reach 34 knots at wide-open throttle.

Although launching often appears more dramatic, landing amidst larger swells is what gives most dory skippers the cold sweats. While running this dory downwind in a larger swell out at sea, I find its wide, flat bottom acts a bit like a surfboard, easily slipping down waves ahead of the danger zone at the wave crest. In the surf zone, I stay well away from following waves. What the Hunky Dory does so well, with enough power applied, is accelerate swiftly on command when the leading wave crumbles. Ideally, it glides in on a carpet of bubbling foam to a casual slide on the sand. I sometimes time it wrong, and land with a stinging slam on the leading edge of the wave, but the boat handles it with ease.

Two design features I have learned to appreciate are the 30-degree angle of the sides and the spray rails. Compared to other dories with sides several degrees closer to vertical, the Hunky Dory has ample flare at the bow to provide an extraordinarily dry ride in nasty conditions. The sides also have much finer, more pleasing lines than the bathtub-like 20-degree hulls. The spray rails keep the spray low and less likely to be picked up by wind; they also added significant rigidity to the plywood sides’ spans between frames.

The Hunky Dory is a versatile design, although it is in some ways too much boat for many inland waters and has too much flat bottom surface area to be practical for moving at speed in waters known for chop. However, this tough, stable boat delivers you through the surf to productive fishing resources in a big ocean. For that alone, it’s a magical thing. ![]()

John Goodell is a wildlife biologist and museum professional, currently serving as the Executive Director of The Archives of Falconry, in Boise, Idaho. He grew up in New England, and during stints in the carpentry trades he developed an interest in traditional dory and skiff designs in regional settings. He somewhat regrets choosing terrestrial professions in place of a life on the water. Before this project, he built a Chestnut Prospector strip canoe, and assisted in a Lumberyard Skiff build.

Hunky Dory Particulars

[table]

Length overall (standard)/22′10″

Length overall (inboard)/22′

Beam/8′

Hull weight (approx.)/1,000 lbs

Hull depth forward/4′2″

Hull depth aft/2′8″

Bottom width/5′

Minimum recommended power/30 hp

Maximum engine weight/700 lbs

[/table]

Plans for the plywood Hunky Dory are available from Glen-L for $167.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I really liked this article. I grew up fishing out of a double end dory with my father in the early 60’s, we would row out through the surf at Cape Kiwanda, two sets of oars, then put a 5-hp motor in a motor well, and make it out past Haystack Rock, and plenty of fish. My father invested in a square-stern boat around 1968 and for the next 4 years, my brother and I commercial fished out of Pacific City. The boat was not well built, and we sold it, and purchased another boat, for pleasure fishing, and some time later, sold that boat as well. And now my younger brother has a fine PC-built dory, named the PEYTON ANN, and she is a stout-built boat. I am 66 and I think back on the history of dory fishing, from the time I was 6. So many good memories and friends made. And, of course, amazing fish stories to be told. The story of this boat, is, in my mind amazing, and I love hearing about it.

I later purchased an Arima boat for rough waters, and fished that for 20 years. Not a dory by any means but able to battle rough waters. So many happy memories.

I really enjoyed the article and have been a huge fan of the Hunky dory. As a dory owner myself and utilizing it at shoal depths, I would like to know more about the material used on the bottom of the boat in the article.

Thank you

Hi Gary,

Other than the double 3/8″ plywood on the bottom, the chines, bottom transom bow have two layers of biax tape, and the 10-oz glass on the sides overlap onto the bottom about 6″ and the bottom glass is one layer of 24-oz, if memory serves, that is also overlapped onto the sides about 6″. Then I rolled on a mix of epoxy, about 2/3 graphite, and 1/3 WEST’s 422 barrier coat…plus a bit of silica to resist running everywhere on application and to make it harder.

If I were to have done it again, I might put a couple additional layers of 10-oz on top of 24-oz just for the bottom then put twice as many coats of the graphite mix….for no other reason than its the one time the boat is upside down so might as well. Currently I roll on the mix once a season on just the “hot spots”. The only significant wear only happens hitting a steeper dry beach on high tide, or hitting rocks occasionally. But it’s easy to trowel on some more to fill small gouges.

Very nice. Can I ask what brand and color paint you used? It looks really sharp against the black.

Hi Stephen,

I used the “Green-Grey” from Kirby Marine Paints (Massachusetts). Very nice paint and was very easy to apply a nice finish with despite being a bad painter myself. There are other colors in their inventory that are similar but the green-grey has a more subtle look compared to the brighter greens…and has a lot of different hues in varying light.

I served in the Air Force at Mt Hebo, Oregon, in the mid to late ’60s and used to fish with my father in law out of P.C. for years. There was a dory named HUNKY DORY fishing the area that I saw in 66-67 and probably before and after that time frame. I can attest to how great of a design these dories were. Ours had the well for the motor and was one dry boat.

John