From all the refined creations of the designer Iain Oughtred presented in the intriguing biography A Life in Wooden Boats, written by Nic Compton, one particular boat, the 14′11″ Elf, caught my eye and imagination. Based on Norwegian faerings with roots in the Viking era, the small but intrepid-looking Elf is a fascinating adaptation of ancient design to modern construction. I had built a couple of glued lapstrake plywood canoes, so the Elf was a natural choice for me.

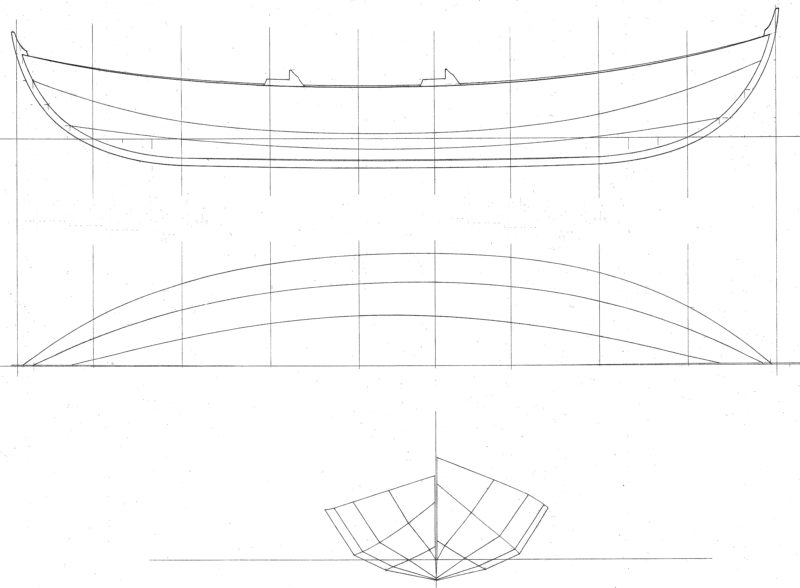

The original faerings were built by hand and eye, and had slowly evolved during hundreds of years to meet the local conditions and particular purposes. Iain carefully studied every design and photo he could find, realizing no two faerings were alike. He had a commission for a boat smaller than the original ones, and after absorbing all he could find on the subject, he began drafting his own interpretation of the faering, adapting the structure for glued-lapstrake plywood.

Mats Vuorenjuuri

Mats VuorenjuuriThe Elf has many traditional elements—broad strakes, rangs (angled frames in the ends), kabes (wooden row locks)—and only the daggerboard trunk and the absence of lap rivets betray its modern construction. For rowing, a plug for the daggerboard case will keep water from splashing into the hull.

Iain’s plans are famous for their elegance and detail, and Elf makes no exception to this. The package includes full-sized templates for the building molds, frames, and stems plus lines plan, construction plan, detail patterns, materials list, and construction notes. Add Iain’s own informative book Clinker Plywood Boatbuilding Manual, and you should be good to go.

Iain recommends 9mm okoume or 7mm mahogany plywood for the hull and Douglas-fir, larch, or pitch pine for keel and frames. There are only two laminated frames in the center of the boat and smaller canted frames—rangs—aft and forward in the hull. The center and forward thwarts are installed aligned with the main frames further reinforcing the structure.

With basic woodworking skills, tools, and some practice in using epoxy, building Elf should not be too demanding. One critical step is to get fair and accurate lines on the three wide strakes of the hull. This can be achieved using plywood or bendy strips attached together to make patterns to transfer plank shapes from the molds.

In his book, Iain constantly uses various clamping methods to avoid the need for screws. Moving forward with the building process, I started to understand and appreciate this method more and more. The benefits of avoiding screws are less screw removal, fewer holes to be filled later, and perhaps a more elaborate structure. There are some stages where screws are necessary and unavoidable to get parts set correctly for gluing.

Sanna Virnes

Sanna VirnesElf is a joy to row, it moves effortlessly and tracks exceptionally well. The hull is quite full forward, so, for rowing alone the forward thwart is a good choice, especially when traveling downwind. Some gear or ballast aft, will help put the keel level.

As the hull comes together, you really begin to admire the simple and functional structural design of the boat. Realizing the unadorned beauty of Elf, you will think very carefully before adding anything but the necessary fittings into the boat. It took a whole year before Iain dared to equip his own boat with sailing gear, and to that end, a slot for the daggerboard is cut to one side of the wooden, full-length keel and the daggerboard case is fitted forward of the center thwart. Iain has drawn a beautiful Norwegian-style rudder, and there are two options for rudder fittings. One has a long, curved rod held by two stem fittings that allows the rudder to be positioned high on the stem with the blade nearly clear of the water for rowing or beaching, or low with the blade fully submerged for sailing.

I chose a more conventional solution of common pintles and gudgeons and remove the rudder when I’m not sailing. With the 5′-long tiller, I can easily steer even while sitting in the middle of the boat.

The plans include drawings for oars and the traditional oarlocks called kabes. The oars are locked to kabes using rope loops. The loops need to be measured and spliced carefully for both a smooth rowing experience and to allow shipping the oars. The 9′ oars for the Elf have looms with flat backs and bottoms that fit the kabes and set the blades at the proper angle. The blades are long and narrow; their shape catches little wind while being effective.

The Elf weighs only 143 lbs and can easily be pulled up on a beach or onto a trailer singlehandedly, and two people can carry it. I bought a pair of inflatable beach rollers for effortless and harmless beaching; they fit under the thwarts when not in use and serve as flotation.

Once you get the Elf in the water, it will feel tender at first, but stable when you get settled on the thwart. Then the very first strokes will put a smile on your face. The hull resistance in slow speeds is remarkably low, and the boat is very easily driven. A peaceful pace for this boat is 3 knots, and by adding some effort, a knot more can be achieved. This seems to be the hull speed. The full-length wooden keel provides excellent tracking, and she turns smoothly. Because the Elf’s bow is much fuller than its stern, the forward thwart is the best choice for rowing alone; putting some gear or ballast in the stern will achieve proper fore-and-aft trim. For solo rowing, when the wind is abeam, rowing from the aft station will help prevent the hull from turning into the wind.

Mats Vuorenjuuri

Mats VuorenjuuriWith two rowers, Elf balances up nicely and maintains good speed with little effort. The 3′ spacing between the rowing stations is just enough for two well-synchronized rowers.

Because the span between the aft station’s kabes is 4″ less than the span at the forward station, you will lose some leverage rowing aft. For tandem rowing, the space between the two rowing positions is just enough.

The extreme lightness of the Elf has its virtues and drawbacks. It takes very little to move it, whether under oar power or sails. Lightly loaded, the hull sits high on water, and the upswept bow and stern add to windage. Although the hull can handle rough wave conditions, rowing against even a moderate breeze can be hard work. Waves also have an effect on the light hull, and its lack of momentum while tacking can lead to getting caught in irons. After you steer through the eye of the wind the Elf will start flying; off the wind it will accelerate quickly to surf down waves, occasionally exceeding hull speed.

Once you step into the Elf you are more than doubling its displacement, making it sensitive to both longitudinal and transverse trim. This can be disconcerting to a novice, at least to begin with, but very useful to an expert sailor accustomed to trimming and ballasting a sailing dinghy. The magic of faerings is in a narrow waterline beam for fast rowing, and a ’midships flare for ample reserve buoyancy to resist heeling while under sail.

Pasi Ehrola

Pasi EhrolaElf is well mannered under sail. Once the ample flare in the midsection hits the water, the hull stiffens up considerably.

Elf sails quite well even without the daggerboard. Before I installed the daggerboard case, sitting on the floor in the center of the boat was a sweet spot when sailing alone. The push-pull tiller rests conveniently on the center thwart, and I had unobscured views under the sail. When the wind picks up, you get more leverage from body weight by sitting on the thwart, or by hiking out on the gunwale. Sailing with a family of three aboard was also comfortable—my daughter would sit in front of the mast on the floor, I steered while sitting between center and aft thwarts, and our third crew sat between the center and forward thwarts. Loaded this way, Elf is very forgiving and stable.

Adding the daggerboard resulted in faster tacks and better windward performance. If you have camp-cruising in mind, I would seriously consider dispensing with the daggerboard and case to get good use of the stowage space in the center of the boat.

Gene Williams

Gene WilliamsThis Elf, built by Duane Mathes, carries the sprit rig that is detailed in Oughtred’s plans.

I deviated from the plans for the sailing rig. The plans call for a 53-sq-ft sprit sail, but I opted for a lugsail of similar size; lugsail is also a choice of preference by Oughtred for Elf’s big sister, the 16′ 6″ Elfyn. As designed, Elf’s mast is supported by an extra partner fastened at the sheer. I wanted to minimize the structures and have unobstructed access to the bow, so I used the forward thwart as the partner. With this arrangement, the mast bury is quite small, so I stayed the mast using the halyard as one stay, and a dedicated line as the other. Eventually, finding the right tweaks for the lug sail, balance was good. The area of the balanced lug sail that sets forward of the mast compensates for moving the mast location a little bit aft, so the center of the sail’s overall area is very nearly the same as that of the spritsail.

As Iain remarked about the Elf: “Getting such functional efficiency in such a simple shape is astonishing.” Build an Elf for rowing, sailing, or wandering solo with a light load of camping gear, you can hardly go wrong. Elf is packed with character. Give it time and opportunities, and it will eventually charm your eye and steal your heart.![]()

Mats Vuorenjuuri is the father of three and an entrepreneur, making a living in graphic design, photography, and freelance writing. He is currently becoming a boatbuilder as well, offering boatbuilding and maintenance services through Nordic Craft. In recent years he has discovered the simplicity and joy of small boats after sailing various types including sail-training schooners. He wrote about cruising the Finnish coast in his Coquina in our May 2016 issue and about a Lakeland Row in January 2017.

Elf Particulars

[table]

Length/14′11″

Beam/4′4″

Sail area, lug/52.72 sq ft

Weight/143 lbs

[/table]

Plans for the Elf are available from the WoodenBoat Store for $204 USD (study plans are 99 cents) and from Oughtred Boats for $224.44 AUS.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

These are such lovely boats, and so very well behaved in heavy going. My own IRONBLOOD has less flare in the upper strake, and I built in lockers at the ends and a full-length keel to avoid a trunk amidships. But IRONBLOOD was built to simply be an island-hopping beach cruiser. Your Elf has such pleasing lines and looks to be a lot lighter and so, easier to row than IRONBLOOD. Nice article, nice boat. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you, Michael. I guess most boats will surprise you in some way once you get them on the water. Elf surprised me with how natural and comfortable it was to sail while sitting on the floorboards. A trunk does interfere with this when sailing with company.

A good story. A couple of brief Comments: The bow may look full, but the entry at WL is very fine for minimal resistance; the great flare, and the Norwegian-style broad bow in plan view, with the maximum beam forward of amidships, is for a very buoyant bow, which will lift to steep waves, and even enables pulling out into a moderate surf. And a breaking wave coming beam-on, threatening to swamp the boat, is nothing; she just lifts lightly over it, remaining upright, unlike a beamier WL hull with more initial stability, which would roll dangerously.

These are light rowing craft, and tender under sail, so need constant attention in a gusty breeze; but need little sail area to move them along.

The Elfyn has the same structure; 16′-6″ x 4′-9-1/2″; around 180 pounds. Sprit or lugsail, 65 sq. ft.

Sources of plans: WoodenBoat Store. Or myself at [email protected]; Struan Cottage, Bernisdale, Isle of Skye, Scotland IV51 9NS. Or StrayDog BoatWorks.com (S Australia).

Looks similar to Chesapeake Light Craft’s Skerry – both are double-ended, both row easily at 3 knots, sail fast, are a tad tippy, and both have the long tiller. Elf is about 50 pounds heavier; for my Skerry if planning to sail, I take along 20 to 30 lbs additional ballast for placement under the middle thwart astride the daggerboard case. For sailing, I sit on the aft floorboard too. Both are fun, attractive, lightweight quick-rigging boats that sail and row quite well.

Thank you, Mats, for this excellent article and especially for the photographs. I have an Elf in build at the moment and it is most encouraging to see how things should turn out!

Launched my Elf build on March 11, 2021. Here is what I wrote to my TSCA Raleigh chapter group:

Elf was named as he launched as TOL – the icon on his side depicts the Tree Of Life = TOL

I found this to be the one boat in the 16 I’ve built that performed exactly as I was expecting it to. It’s beamier and slightly shorter then a Joel White Shearwater albeit just a tad slower but also a tad more stable. I wanted a row boat that combined the best of the Shearwater and a Peapod as rowed up in WBS in 2019 and I was not disappointed. Not quite as stable as the Pea but faster with more LWL. He was lithe under oars with the ability to tightly turn more so than a Whitehall, less then a Nutshell pram, but right in that sweet spot in between, like the Joel White Shellback Dingy. Tracking was so much nicer than in the dory, especially when the wind picked up, as he stayed true to course with minor adjustments on the oar pulls. The 9 footers worked well, perhaps slightly over-balanced outside, but the looms could be crossed at the hands for that type of rowing. Ill go with the 8’6″ next time to see the difference. When the wind picked up I was more aware of the resistance on the long blades of the Shaw and Tenney’s when out of the water than on the boat itself. Practical Elegance was achieved.

The boat at left is a Skerry; my Elf is at right.

Hey Mats, I don’t know if you’re still checking these comments, but this is Duane, the one with the spritsail in the image above. I am curious how you have yours rigged. I had a pretty gnarly uncontrolled gybe last weekend where the sheets were ripped out of my hand in heavy weather, and now I’m rethinking my setup.