Whenever a simple and delicious Mexican idea migrates north across the border, it tends to get fancied up, often to its detriment. Consider the nacho, once an unpretentious tortilla chip crowned with a slice of jalapeño and melted cheese, now a heaping muddle of meat, sour cream, onions, olives, and herbs. Herbs! Sam Devlin’s new Pelicano, a liberal translation of the Mexican panga workboats, has likewise been garnished with such gringo delicacies as windscreen and wheel steering, but it’s hard to complain that it’s been spoiled in the process. Devlin’s version is saucy-looking, efficient, and seaworthy, and still unfancy enough that an ambitious amateur can realistically aspire to building one.

Devlin got acquainted with pangas on his occasional winter trips to Mazatlán, one of which also acquainted him a few years back with a delightful woman named Soitza, who became his wife. Mazatlán glares out at the open Pacific, and Devlin says he was impressed by the pangeros’ willingness to motor out into the big water to fish—at least in the mornings, before the afternoon trades boil up—and then drive the boats right up onto the beach around noon. He liked the pangas’ no-nonsense functionality and tough character, but the all-fiberglass execution left him cold.

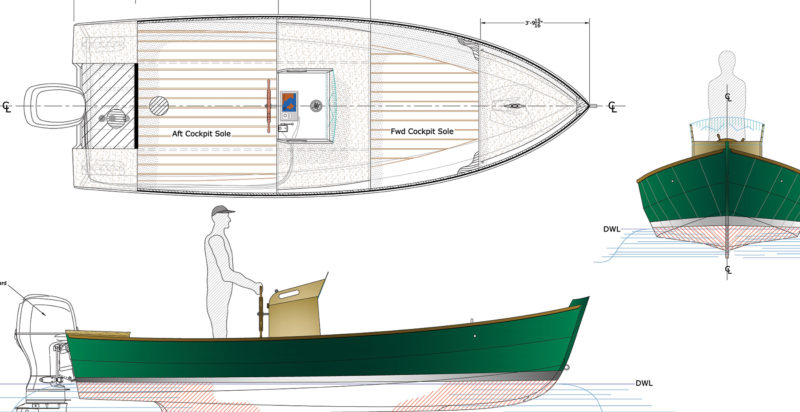

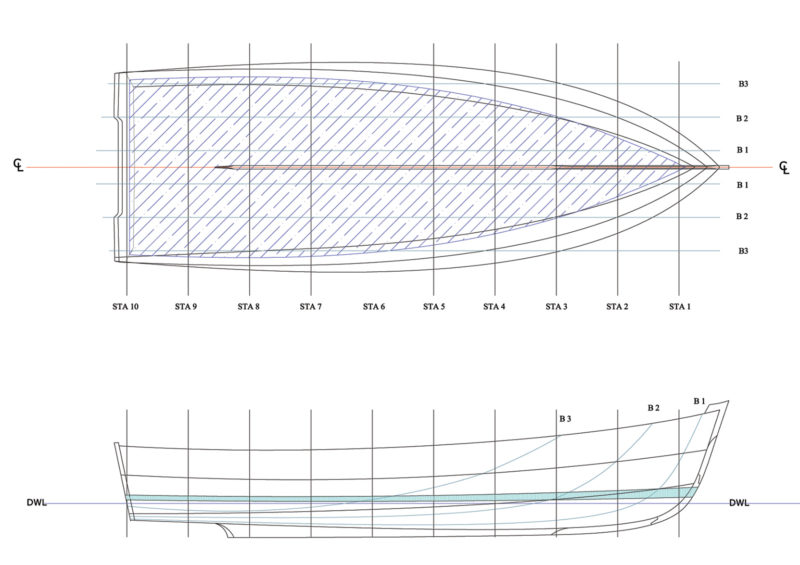

For his interpretation, Devlin shortened the hull from a typical 22′ to 18′ 4″ for handier trailering. He added a deck, kept the beam slender at 6′ 6″, and gave the bow an arrowhead-fine entry with a prominently extruded stem. “I’m a big fan of parting the water,” he says. It’s a semi-displacement hull, so its transition to plane is gradual and subtle, and Devlin’s design objective is the best possible compromise between low-speed fuel efficiency and high-speed—well, speed.

Neil Rabinowitz

Neil RabinowitzThe Pelicano shrimper offers an impressive level of accommodation and ease for an 18-footer, for it has sheltered steering and bunks for two adults, while also being easily trailered behind a small pickup truck.

Devlin never undertook any formal education in naval architecture, but has quietly amassed 35 years of experience designing everything from kayaks to motor cruisers now threatening 50′. (He recently moved into a vast new industrial park-type shop, in part so he could bid on regional ferry projects—stitch-and-glue ferries, of which he’s already built one.) He loves to riff on historic boat types, everything from melonseeds to classic wooden tugs, but he’s always thinking contemporary practicality, efficiency, and simple beauty. Two things about a Devlin design: You’ll never see any fussy, superfluous gimmickry. And unless you have a practiced eye, you’ll never guess they all start out as a pile of plywood. Devlin’s boats are closer to the sculpture garden than the lumberyard.

Pelicano plans are available in three configurations: center-console, bassboat, and shrimper. The center-console edition shaves the building time by about 150 hours and provides, in effect, tandem cockpits separated by a bridge deck. The shrimper features a tall pilothouse rising over a rudimentary cuddy, and a longish cockpit. Either of these would make a versatile fishing boat. Devlin’s personal favorite is the bassboat, which is really more of a picnic cruiser. The cockpit provides space enough for only three or four people, and the cabin is slightly higher than the shrimper’s, providing sitting headroom for a fireplug-proportioned person and camp-style sleeping room for two. It might be the least versatile of the three, but it’s the most fetching: a simple, exquisitely proportioned classic design that stands proudly aside from transient commercial trends.

Neil Rabinowitz

Neil RabinowitzThe Pelicano bassboat (foreground) is Devlin’s preferred layout; it has room for (in addition to two berths) a galley and stowage.

On a crisp, calm summer morning we splash the bassboat into a southern finger of Puget Sound near Devlin’s shop and play for a couple of hours. The wavelets are all of two inches high, so we have no chance to test her in a chop, but Devlin spots a big cruiser and arrows the Pelicano across her wake. It isn’t much of a challenge, but the very steep V of the entry seems to settle the bow back into the water with cushioned delicacy. The hydraulic trim tabs—another unlikely garnish on a Mexican workboat—negotiate the bow downward so we can easily peer ahead over the deck at speed. This boat’s 70-hp Yamaha—about the maximum motor Devlin recommends—yields a 17-knot cruise at 4,000 rpm. Top speed is about 25 knots. A water-skiing indulgence would be a foot beamier and faster on plane, but this hull’s skinniness renders it more efficient at fishing velocities. A 25-hp motor, Devlin says, wouldn’t be a bad choice.

The flat, two-piece windscreen is surprisingly efficient at deflecting the breeze from the cockpit, even for aft passengers. The stem extension poking over the deck makes a jaunty gunsight for holding a course. The one aesthetic quibble I’d present is the factory-made aluminum deck hatch, which seems as appropriate on a wooden boat as an electronic organ in a Baroque cathedral. This Pelicano cries for a handcrafted hatch cover to echo its windscreen frame. Devlin, however, is no sentimentalist. While he’s meticulous about the artistic issues of line and proportion—a home builder will wreak remarkable damage by sneaking an extra inch of height into a Devlin cabin—he doesn’t like anything that causes extra fuss, either in construction or maintenance. His philosophy is: simple, strong, durable. On this boat, sprayed-on polyurea truck-bed liner, which has the texture of lizard hide, covers every square inch of deck, cockpit, and most of the cabin interior. It hardly offers the warm-blooded allure of teak or mahogany, but it’s no trouble, either. “It’s just the coolest stuff,” Devlin raves. “I love how much protection it gives the epoxy.”

In fact, on this Pelicano from Devlin’s shop, only the sapele windscreen frame and companionway slides suggest “wooden boat.” Indeed, most casual onlookers wouldn’t guess that the heart of this boat is wooden, given the high-gloss topside paint and professional-quality fairing. Most amateur builders, however, won’t have that problem: Our fairing will not be so fair, and we’ll be tempted to allow more brightwork than Devlin does, despite the penalty in maintenance. It really distills down to how one wants to balance “boatbuilder” with “boat owner” and “boat user.”

Neil Rabinowitz

Neil RabinowitzDesigner Sam Devlin and his wife, Soitza, enjoy an outing in the Pelicano bassboat

Let’s talk about building for a minute. Like all the 90-odd designs in Devlin’s current catalog (www. devlinboat.com), this boat is made of stitch-and-glue plywood with exterior fiberglass-and-epoxy sheathing. The ply is ½”. Unlike many of his earlier designs, however, this hull is intended to be built upside down over four bulkheads on a strongback, then ’glassed and faired before righting. The advantages, Devlin says, are easier fairing and the need to convene neighbors only once for flipping. The keel is a beefy slab of purple-heart, 1¼” thick, capped with a stainless-steel or bronze quarter-round. “Sometime in the life of this boat it’s going to get beached,” Devlin says. “Might as well prepare for it.”

Although this is basically a simple boat, the amateur should not expect to begin building in the fall and happily launch in the spring. Devlin says there are about 1,400 shop-hours in each of the two Pelicanos his crew has built to date, and let’s note that those are professionals’ hours. Based on my own experience building a Pelicano-size sailboat of Devlin’s design (the Winter Wren II), I venture that a typical amateur will need about twice that long, and Devlin readily agrees. However, the cabin is a monumental labor pit on any boat, so the center-console version of the Pelicano should be substantially simpler.

Neil Rabinowitz

Neil RabinowitzInspired by outboard-powered skiffs—pangas—he’d encountered in Mexico, Sam Devlin drew the 18’ Pelicano hull. He offers three different layouts for the boat: center-console, bassboat, and the shrimper seen here.

As with some other designers, we have our choice whether to commission a Pelicano from Devlin’s shop or buy the plans and attack the task ourselves. The Pelicano teeters on the cusp of being an appropriate first boat for the amateur: probably accessible to the moderately skilled and highly determined, probably not to the woodshop-clueless and easily distracted. The question then becomes one of balancing the prize of flawless finish and detailing against personal growth through accomplishment. Spending a morning with Devlin’s Pelicano made me a little dejected and irritable with my amateur craftsmanship on the Winter Wren, but also determined to keep improving.

Which is exactly what seems to keep Sam Devlin cranking out boat plans. After two boats and a number of long conversations, I know him pretty well, and I’m convinced that he enjoys seeing his customers grow into real boatbuilders at least as much as he savors the beauty—and revenue—of finished boats rolling out of his own shop. “I’m interested in boats, my customers, and making money,” he says. “Probably in that order.”

![]()

The Pelicano center console is the simplest of the trio. This boat’s center console is hinged; when it’s pivoted forward, a large cargo hold is revealed in the hull.

Pelicano Particulars: LOA 18′ 4″, Beam 6′ 6″, Draft 12″, Dry weight 1,490 lbs, Recommended power, 25–70 hp outboard

Finished boats and plans for the Pelicanos are available from Devlin Designing Boat Builders. This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2012 and appears here as archival material.

In my opinion, the features of panga include; lightweight, narrow beam, floatation bulge around the gunwale, and delta pad.

Comparing to a J-18 Imemensa panga. J-18 is 473lbs Pelicano is 1490lbs. J-18 has a 60″ beam, Pelicano ha a 78″ beam. J-18 has a floatation bulge around the gunwale and a delta pad, Pelicano has neither.

I love the boat, particularly the Shrimper model. I think some strip planking above the chine midship to the bow would remove the feature line forward and I would be in love. Great job, Devlin.

Great Boat, right up my alley. More like the practical cruisers that are made in UK and Europe. Fuel efficient. Like cars in US if more was done for fuel efficiency like slower speed limits and less weight we would not need to go electric. Devlin has good practical boat designs. Saw my first at the Seward, Alaska, boat dock years ago, a Devlin small tug type of some sort. I bought a 19′ cruiser last year here in Alaska. Wondering what it is? A Glen-L or? A couple of photos are linked here. Many folks here are not very water savvy and get huge aluminum or glass boats to play at bottom fishing etc. Many are afraid of water/seas so have to go large.

Transom view

Side view

Seen Pangas here in Hawaii. My cousins are watermen in the two Rivers (Rappahannock and Potomac) area of Chesapeake Bay. To me, this hull shows more descent from Chesapeake Bay deadrise workboats than Pangas. When I see that sharp entry and deep vee forward flattening out as you go aft I think of blue crabs and oysters!

Being from the Chesapeake myself I have to agree with you. A lot of Chesapeake boats descended from work boats further North like New York, but I guess all the various US designs had their original ideas from Europe. Chesapeake watermen boat builders up until the ’80s could build Rack O’ Eye that means from memory, no boat plans or many measurements.