I live in an area where there are a lot of quiet sloughs, little lakes, and slow-moving rivers, but there are only a few launch ramps. With my trailered boats I have been going to the same four places for decades and feel cut off from all the opportunities the region has to offer. I can cartop my canoe, but it’s too heavy to carry and requires a cart, and my kayaks are all long enough to be awkward to carry and not well suited for narrow winding streams and half-acre ponds. Iain Oughtred’s Stickleback may be among the smallest of small boats, but I wouldn’t regard its diminutive size as a limitation. On the contrary, it would be just the right boat to overcome the limitations of all of my larger vessels.

Photographs and video by the author

Photographs and video by the authorThe 37 steam-bent frames give a traditionally planked hull the look and appeal of the double-paddle canoes of the 19th century. Glued-plywood lapstrake construction has the advantage of a more easily maintained interior.

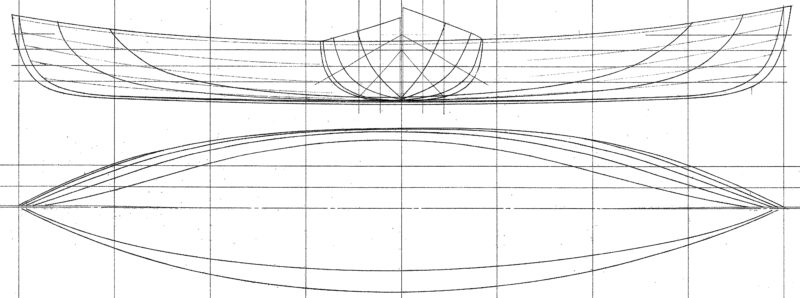

The 10’8” Stickleback is the shortest of the four canoes in Oughtred’s catalogue. The plans include five sheets of drawings and a “plans supplement” that has 14 pages of general instructions for the construction of his canoes, dinghies, and Acorn skiffs. While there is adequate information in the supplement for building the Stickleback, Oughtred’s 174-page Clinker Plywood Boatbuilding Manual has more drawings and lots of photographs that first-time builders will find quite useful. The Stickleback drawings provide both imperial and metric figures, and while offsets are included, there are full-sized patterns for the seven molds and the two stems, so you can skip bending over a lofting and tweaking fairing battens. There are also full-sized patterns for the breasthooks, deckbeams, side-deck knees, and backrest as well as measured scale drawings and full-size plan and profile patterns for an 8′ spoon-bladed paddle.

The double-bladed paddle described in the plans is 8′ long and has a blade 21″ by 6″. A 1-1/4″ copper tube is suggested as a means of joining the two halves—feathered left, right, or unfeathered— but not as a take-apart paddle. In the one-piece feathered version that Tom, pictured here, built, the two halves are permanently scarfed together.

Oughtred offers a number of options in the plans. The alternate station spacings he suggests can make the canoe 10′2″, 10′8″ (standard), 11′2″, or 11′6″. The Stickleback can be built as an open canoe with open gunwales or as a decked canoe with sealed compartments in the ends. The compartment bulkheads lie on the same stations as the temporary molds, so you’d use 4mm marine plywood as the molds for stations #2 and #6 and epoxy them to the planking. Hatches in the bulkheads would provide access for dry storage spaces. The patterns for the molds are marked for planking the hull with five strakes for glued-lap plywood or seven strakes for plank-on-frame construction, but don’t provide scantlings for frames and planks. The Stickleback shown here was built in the traditional manner by Tom Regan of Grapeview Point Boat Works in Allyn, Washington. He took the 3″ frame spacing from Rushton’s description of the 10’6″ Nessmuk canoe in his 1903 catalog: “Ribs, very light and spaced 3″.” Rushton’s legendary SAIRY GAMP has 5/32″ x 7/16″ frames, and were likely red elm, as with his other canoes. Tom made his frames 3/16″ x 3/8″ so he could edge-set them a bit easier if required. He had milled up white oak frames, scrapped them because the were too heavy, and ultimately used Alaska yellow cedar.

Weighing less than 20 lbs, a Stickleback is an easy carry.

The plywood version of the canoe is meant to have a floor of 3 or 4mm plywood spanning the keelson, garboards, and first broadstrake. Glued in place, it will stiffen the hull under the paddler and provide a little elevation to keep the seating area dry. The open space between the hull and the floor is not sealed off at the ends of the floor, so care should be taken to have those inaccessible surfaces well sealed with epoxy before assembly and hosed out after paddling to avoid accumulations of sand and leaves. The backrest in the drawings is 11″ wide, 2-3/4″ from top to bottom, cut with a curve for comfort and fixed to a laminated arched deckbeam at station #5. Another deckbeam, shown installed just aft of station #2, serves as a foot rest. Its position could be altered to best suit the leg length of the paddler.

At its designed waterline, the Stickleback draws 4-1/4″, and with 220 lbs aboard, it needs not quite 6″ of water to float free of the bottom.

Tom’s Stickleback was made of Sitka spruce and Alaska yellow cedar; it weighs a mere 18 lbs; 2 lbs under the 20 lbs Oughtred indicates for the plywood version. Either makes for an easy carry. With a removable carrying yoke spanning the gunwales amidships, I wouldn’t balk at carrying it a mile or more if there were a jewel of a hidden lake to be paddled.

The gunwales amidships are low and close in, well out of the way of a relaxed stroke.

Getting aboard the canoe is a bit dicey. Tom sets a foot on the floorboards, holds the gunwales, and sits down quickly as he brings the other leg aboard. That leaves his weight up high for a moment, and the canoe gets rather twitchy, but he has yet to take a dip at the launch. I straddled the bow and sat down on the floorboards just aft of the forward thwart, then brought both legs in at the same time as I slid back into paddling position. That kept my weight low and the canoe stable as I got aboard, but the method requires legs long enough to bend around the gunwales. Both my method and Tom’s were meant to preserve the varnish. If that weren’t a concern, I would use a method that’s common with kayakers: Put the boat afloat parallel to the shore, set the paddle across the deck/gunwales with one blade extended shoreward and resting on the land. Then the paddle can take your weight and stabilize the boat as you drop into the seat.

While the plans call for a backrest fixed to the arched thwart, leather hinges assure you get the broadest area of support and have no edge pressing against you.

Once I had planted myself on the floorboards, I was quite comfortable and stable. Tom had mounted the backrest with leather hinges instead of gluing it, so it settled flat against my back. The toes of my size 13 feet were high enough above the floorboards to get a solid purchase on the thwart that serves as a footrest, though with my leg length I would have prefer having the thwart about 2″ farther forward.

Running between 3 and 4 knots, the canoe can cover ground quickly and provide good exercise.

My 220 lbs was as much as the canoe could handle comfortably. One of the longer versions made by increasing the station spacing would have been better scaled to me. I had about 5” of freeboard and if I leaned to the side I could get water to lap over the gunwale. The canoe felt stable for as far as I could lean it without swamping. Tom, at about 150 lbs, had around 6″ of freeboard, and while it might seem that he’d be able to take on rougher water than I, the boat isn’t meant for venturing out in wind and waves. The lake we paddled for my trials was only 150 yards wide and well protected, an environment well suited to the Stickleback.

Like the Rushton lapstrake canoes that preceded it, the Stickleback is designed for use with a double-bladed paddle. I did most of my trials with a double-bladed paddle, but I had no trouble paddling on one side, as I would with a canoe paddle, incorporating a ruddering finish to my stroke. I wasn’t sitting high enough to paddle with the J-stroke used by canoeists. A single-bladed paddle would make a reasonable spare to carry aboard.

The 27″ beam, located at about hip level, doesn’t get the least bit in the way of paddling. As I’d expected, the Stickleback was quite nimble and fun to maneuver through tight turns. I was limited by freeboard to only a modest degree of edging, but even that was enough to quicken the turns and keep the canoe carving around between strokes.

The bow yawed noticeably at slow speeds, but in general the canoe stayed on course without veering to one side, a good indication that the backrest is at the right position, putting the paddler’s weight just aft of center and pressing the stern down slightly deeper than the bow.

Tom Regan

Tom ReganWhile speed isn’t going to be a strong point for any canoe under 11′ long, the Stickleback can move smartly, track well, and maintain its stability when pushed hard.

I was surprised by how fast the Stickleback felt. Sitting low on the water exaggerates the sensation of speed, but the canoe turned in a respectable set of numbers on the GPS. It responded to relaxed paddling with a speed of 3 knots, and to an aerobic exercise pace with a speed of 4 knots. When I put in an all-out effort, I could sprint at 4-¾ knots; the GPS registered a momentary peak of 5 knots. At that speed, the bow throws a wake like miniature PT boat.

While this version looks like strictly traditional construction, there are a couple of significant differences. The planking laps are epoxied, so there are no copper clench nails between frames. The nails visible here are fastened to only a few locations on the frames and elsewhere the frames float. When the yellow cedar planking absorbs water and swells slightly, the planks can move away from the frames rather than strain at fastenings and tear at the laps.

While the traditionally built and bright-finished yellow-cedar Stickleback that I paddled is a strikingly beautiful work of boatbuilding, a glued lapstrake plywood version, painted, with a few accents of brightwork, would lend itself to going paddling often and taking the knocks and scrapes that come with exploring new backwaters. And with its curves accented by the planking laps, the Stickleback would still be a pleasure to look at.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly.

Stickleback Particulars

[table]

Length/10′8″

Beam/27″

Draft at DWL/4.25″

Freeboard at DWL/7″

Weight/20 lbs

[/table]

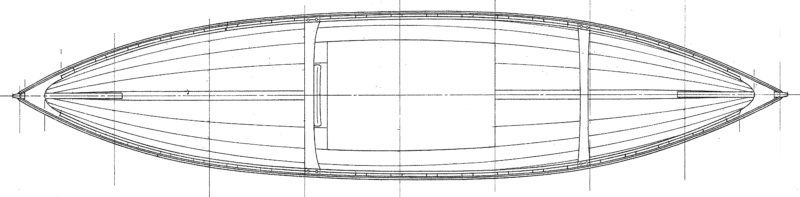

Open canoe option

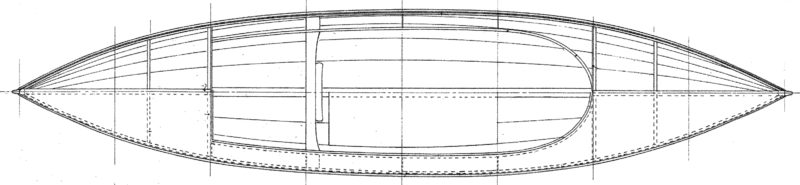

Decked option

Plans for the Stickleback are available from The WoodenBoat Store for $105. Tom Regan of Grapeview Point Boat Works can build Sticklebacks to order.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Reading this article and looking at the pictures took me back to the 1980s and ’90s when I used to exhibit my line of solo canoes (13′-16′) at wooden boat shows where I watched helplessly as hoards of burly men (some well over 200 lbs.) hurried past my display to get to other builders offering Wee Lassie replicas. Don’t get me wrong, these adorable, beautifully modeled craft make wonderful vessels for children and very small adults, but few of those strapping men seemed to consider that the original that inspired those miniature canoes was designed for a 90 lbs. tuberculosis sufferer in a time before outboard wakes were a serious concern. Some of the speeds claimed for this boat in this article are way beyond the efficient hull speed of such a short boat, and some of the waves generated by big, strong paddlers appear steep enough to swamp this boat in the event of a sudden stop or sharp turn. I’m out of the canoe business now, so it’s only as a public service that I say, if you weigh over 120 pounds, and you intend to paddle on something other than protected ponds, you’ll be much better served by a canoe that is 2′ to 5′ longer and 10 to 20 pounds heavier. Rushton designed plenty of them. They’re gorgeous too. Don’t get me wrong: Tom Regan made a beautiful job of this canoe and, anyone who properly fits this diminutive craft, should feel lucky to have it.

For the 1% readers who are expert boat builders. Can’t Ian even design a 10′ canoe that mortals can build?

Just search “Wee Lassie” and you’ll find many options for building this much-loved design. The inspiration was the Wee Lassie canoe made in 1893 by J. H. Rushton for William West Durant of Raquette Lake, New York.

Every builder who sees this great little pond jumper can’t resist making their own version, myself included. While strictly speaking, Andre is right about big guys in little boats. But if I were trout fishing, jumping from pond to pond in a place this canoe was designed for, like the St. Regis Canoe Area, it would be a pleasure to travel so light.

There’s a book , Rushton and His Times in American Canoeing, available through the Adirondack Museum, with an appendix of measured drawings and offset tables, including Nessmuck’s Sairy Gamp.