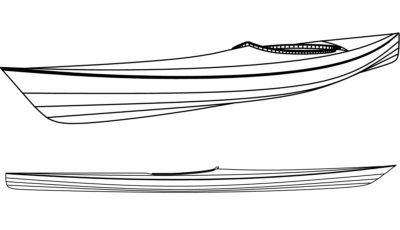

People are always drawn to the warmth and the visual texture of a varnished wood kayak, but the beauty of a plywood kayak can and should be more than skin deep. Not only do the sweeping curves of the Coho 17’s multichined hull and beveled deck offer up an elegance that sets a kayak like the Coho apart from mainstream composite and rotomolded plastic kayaks, but this stitch-and-glue kayak is also lighter and stiffer than fiberglass kayaks and plastic kayaks of similar size. Pygmy’s computer-generated panel shapes and laser-cut templates produce kit pieces that will come together in an exceptionally fair hull that will hold its shape for the life of the boat. [Update: Pygmy closed at the outset of the pandemic. —Ed.]

In Pygmy’s early kits, butt blocks were used to back up the joints required to make the full-length strakes. The blocks have been done away with, and the butt joints are now just glued and ’glassed. They are every bit as strong, a bit lighter, and make for a cleaner interior. The bottom of the Coho has a slight V through the midsection, enough of a crease to give the midsection plenty of stiffness. The triple-chined hull is lined off into four well-proportioned strakes. The deck has a central ridge that sheds water well and beveled side panels that keep the beam of the boat low and out of the way of the paddle.

At just under 40 lbs, the Coho is an easy lift and carry. You won’t find yourself muttering by the time you get it into the water. The cockpit opening was long enough for me (I’m a bit over 6′ tall) to get in seat-first. That can be an advantage over a small cockpit that requires you sit on the afterdeck and slide into the cockpit feet-first. If you bail out of the Coho after a capsize, you can crawl aboard, straddle the deck, and drop your weight into the seat. Most folks will have enough stability then to get their feet in without having to set up a paddle-float outrigger to stabilize the kayak.

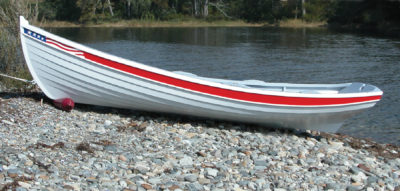

Provided by Pygmy Boats

Provided by Pygmy BoatsStriking from any angle, the Coho 17 kayak from Pygmy Boats weighs less than 40 lbs. The 17′ 6″ x 23″ boat will carry a paddler and his gear through rough water at good speed.

The self-inflating (Therm-a-Rest) seat pad is fairly comfortable initially, but the muscle tension required to keep the legs locked into the thigh braces can eventually lead to fatigue and numbness. The pad also makes for a slightly mushy connection to the boat. For one of my outings in the Coho, I replaced the pad with a minicell foam seat I’d sculpted for one of my own kayaks. My homemade seat is about 15″ long and about 3″ thick at its forward end. Its deep custom-fit contours are more comfortable in the long haul, and the support it provides under my legs keeps my feet from going numb. I also found that the solid connection of the sculpted seat made the Coho easier to control when edging the hull through turns or in surf. If you have rough-water paddling in your sights, carve your stern into a block of minicell.

Once afloat, I felt quite comfortable in the Coho. It has plenty of initial stability so I could set the paddle down and not have to think about keeping the boat upright. Even when the Coho and I were getting slapped around by waves breaking in the shallows, I was able to fiddle with my VHF radio while I had my paddle tucked under my elbow. The Coho has a strong righting moment when set on edge. Canting my hips, I could get the sheer submerged and still feel stable. Only when the coaming touched the water did I feel the stability taper off.

Underway, the Coho tracks well and the bow yaws very little between strokes. The long waterline and sharp ends that contribute to the Coho’s tracking ability will work against you when you try to turn, but a bit of edging will curve the waterline and lift the ends enough to get the hull to carve through a turn. Canting my hips to edge the Coho up to the limits of its stability allowed me to make respectably tight turns. At 17′ 6″ long, the Coho has an appropriate balance between tracking and maneuverability for performance touring. Pygmy offers a rudder as an option, but I don’t think the Coho needs one.

I did several speed trials in the still water using a GPS as a knotmeter. At a relaxed pace I could easily maintain 4.5 knots, a pretty brisk clip for not breaking a sweat. Taking my effort up a notch to an aerobic workout level, I could hold 5.5 knots. Going flat-out over about 50 yards, I could briefly bump up to 6.5 knots. That’s a good set of numbers for a kayak designed for cruising.

Provided by Pygmy Boats

Provided by Pygmy BoatsThis Coho enjoys a quiet day, but it will behave well in tough conditions. Should the worst happen, experienced kayakers can Eskimo-roll the boat. Solid stability and a relatively long (33″ ) cockpit allow for relatively easy re-entry if a paddler must take to the water.

On one outing I picked up a pretty good breeze, about 18 knots. Weathercocking is a common problem among sea kayaks. If you are paddling across the wind, the bow is pretty well locked in as it pushes forward into the water, but the stern, trailing in the turbulent water “softened up” by the passage of the hull, tends to get pushed downwind. The result is that the kayak veers into the wind. Rudders and skegs can easily neutralize this tendency by adding more lateral resistance at the stern. In a kayak that has neither, you can edge the boat to turn downwind or do sweep strokes to push the bow in line, but that can be tiring and annoying in moderate breezes, and dangerous in stronger winds if you can’t hold a course in the direction you need to go. Some kayaks are better balanced in the wind than others, and the Coho seemed to be among the former. The best test of weathercocking, oddly enough, is not out in open water where the waves have been kicked up, but in the lee of low-lying land where you’ll find wind without waves. In rough water the ends of the boat get lifted out of the water, and you can use these moments to make a quick sweep and a course correction. In flat water the entire waterline length is immersed and corrections are harder to come by. The Coho did very well in both circumstances, holding a course well with the wind on any quarter.

I moved out of the lee and into rough water, and the Coho was very steady and predictable in wind waves cresting at about 2′. I never had to slap down a brace for an unexpected loss of balance. In paddling around a point where crossing waves zippered over the shoals, throwing water well over my head, I often had so much water pouring over my eyes that I couldn’t see what was coming at me, but the Coho still stayed comfortably planted under me.

Provided by Pygmy Boats

Provided by Pygmy BoatsBlack elastic shock-cord deck rigging makes for quick and convenient storage of often-used or emergency gear. Note the red-and-gray bilge pump and the bright yellow paddle float tucked within easy reach on the after deck. Watertight hatch covers, each secured by three parallel straps, keep the large stowage compartments dry.

While I was paddling the edge of the shoal, a passing container ship threw its wake into the mix. The first wave to hit, the point’s shallow water pitched up behind me a steep 6–7′ feet. I didn’t get a perfect line down the face, so I surfed ahead at a bit of an angle. The Coho raced ahead of the wave and kept from skidding into a broach. At the end of the ride it was a bit of work to get the Coho turned around to head back out for more waves. It’s a lot of boat to spin around in the break zone. Once I got out for the next set of waves, the Coho accelerated very well so I didn’t have to work hard to catch good rides. In fact, I had so much fun surfing that when I saw a cruise ship coming up the shipping lane I stayed around to wait for its wake.

This latest version of the Coho has a recess in the after deck to bring the coaming down low. The extra clearance made it easier to do layback rolls. The Coho rolls easily but slowly—I think the sharp ends create a bit of drag to rotary motion. I did some wet-exit and re-entry drills. Dropping out of the capsized kayak was a cinch, and so was flipping the kayak upright and getting back aboard. Swinging my leg over the deck released some of the levers that tension the hatch-cover straps. You can easily remedy that by putting each lever in a vise and giving the end a solid whack of a hammer to put a bit of a bend in it.

The Coho is an easy boat to like. It looks good and is well-mannered in a wide range of conditions. The only quibbles I had with the Coho were with elements that the homebuilder can easily take care of when outfitting it. Give it the attention it deserves while you’re building it, and it’ll take good care of you.

The Coho assembles easily: Temporarily stitch together plywood panels with wire ties, then permanently “glue” the panels with fiberglass and epoxy.

Pygmy Boats has been closed since the outbreak of the pandemic and isn’t filling orders. The review is presented here as archival material drawn from the back issue of the print annual, Small Boats 2007.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Fine writeup on the Coho. I built one 4 years ago. It is the fastest of the 9 kayaks I’ve built and the one that requires the most attention to keep upright. I’m sure that more time in it would tame it, like learning a new racing bike. Unfortunately, Pygmy Boats, former maker of the Coho kit, is “in hibernation.” The company was about to change ownership when the COVID financial crash hit. No one knows if the company will emerge and offer kits again.

Dave Elliott

Pygmy’s offerings are very tempting. I built one of CLC’s Chesapeake 15s eleven years ago and find it far too heavy. Have hankered for an Arctic Tern 14 for a long time, but living 16,000 kilometres from Seattle and unable to build from plans a kit would cost a fortune to ship.

Sad to learn that this innovative small company might be in trouble.

I have built two Cohos, one for a man in NY, who for some reason couldn’t find anyone local to do it for him (I’m in Bellingham, Washington). The first one I built for myself in a month (I’m retired, and was single at the time—would have been even faster if it weren’t for having to wait on slow-curing epoxy).

Its first real test was a trip of about 2 weeks in Haida Gwai (aka Queen Charlotte Islands). This was before the epoxy had finished venting off the epoxy blush, so varnishing had to wait until I got home. I found the boat handled well, carried a good load of cargo, and was a pleasure to paddle. Though I know many people who keep trying out different boats, looking for that perfect one, I have been content with the Coho for over 20 years now. Of course the dings and scrapes are starting to show. I’ve found sanding the bottom every few years and coating with epoxy and graphite keeps the part that meets the water smooth.

My kit predated the recessed deck behind the seat, so layback rolls were a little uncomfortable, but certainly doable. I haven’t rolled now for years, since my shoulder went south with arthritis, but I do pretty well staying upright, even in ocean paddling and sometimes surf along Vancouver Island’s west coast (Kyuquot Sound, Esperanza Inlet, Nootka Sound, Barkley Sound, and a couple of long-shore expeditions).

On one west coast trip, Side Bay (north part of Brooks Bay) down to the Brooks Peninsula, our return was about 8 nm of open water along an unfriendly shore and no place to land. The wind was only about 8 to 10 knots, coming onto my starboard eyebrow. It meant a lot of edging and sweep strokes, which was very tiring. “To hell with it,” I thought, “I’m going to put a rudder on the sucker.” Which I did. Don’t have to use it most of the time, glad to have it when needed. I bought mine from a Finnish company, Kajak Sport, because I like the fact that the rudder doesn’t have to swing through a 270-degree arc like most do, but only 90 degrees. From its parked position on the deck, it slides back and down to deploy, vice-versa to park. Very reliable and quick. (I modified the rudder with a couple improvements, but that’s a story for another time).

Even Susan Conrad, who paddled from Anacortes to Ketchikan, admitted that on one long, rough crossing she would have killed for a rudder. I suspect that many folks who scorn rudders would, at times, use one if they had it. Of course, many people are using skegs nowadays.

I put a SmartTrack rudder system on my Coho during the build process. This was my 7th kayak build and I had just not put a rudder on one yet! We do have rudders on the Necky ‘glass and carbon kayaks we’ve paddled for nearly 30 years and we do like having them available when the wind picks up from a quarter.