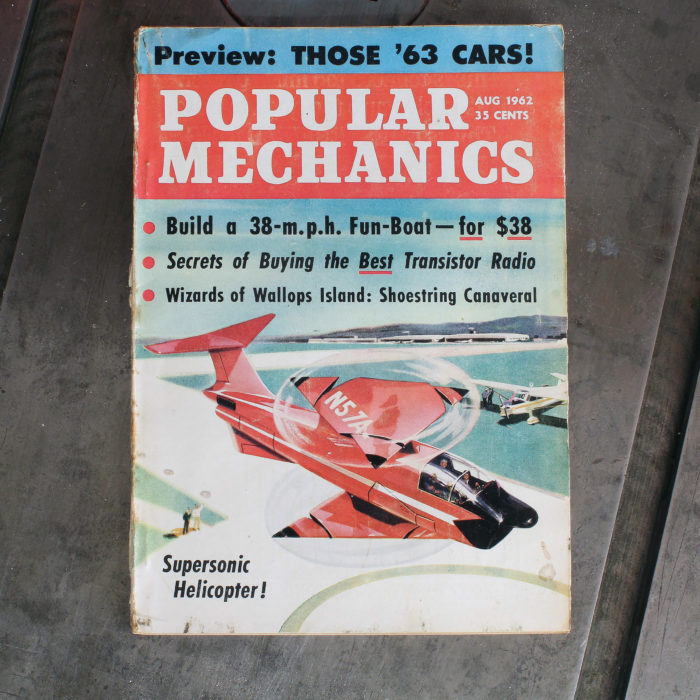

It was the fall of 1962, and I had just started my junior year of high school. I subscribed to Popular Mechanics magazine and was always excited when each new monthly issue showed up in my mailbox, since it contained all kinds of stuff that was interesting to this 16-year-old technically oriented guy. The cover of the August 1962 issue pictured “The Supersonic Helicopter of the Future” (well, that didn’t happen) and teaser—“Build a 38 m.p.h. Fun-Boat—for $38.”

SBM

SBMThe August 1962 issue of Popular Mechanics had 202 pages for just 35 cents. The top billing went to new cars and highlighted the ’63 Studebaker Avanti.

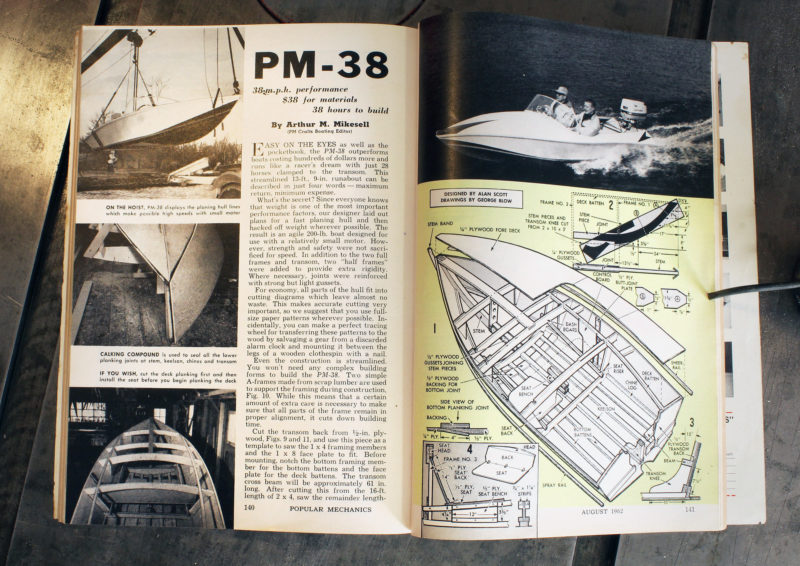

I immediately turned straight to page 140 and read the article. It described how to build a neat little 13′9″ outboard runabout, a PM-38. The “PM” was for Popular Mechanics and the “38” came from a boat speed of 38 mph, a materials cost of $38, and a build time of 38 hours. “Hey,” I thought, “I can do that!” I showed it to my dad, and he said that if I could build the hull, he would find an engine for it.

SBM

SBMThe article on the PM-38 packed a lot of information, drawings, and photographs into 7-1/2 pages.

Our home in the Sunset District on the west side of San Francisco had a two-car garage, but we had just one car, so I had space to build the hull. My grandfather Kelly had a construction business and much of the framing material came from his scrap pile; I saved my allowance of $3 per week to buy other materials and plywood, saving some money by Pa Kelly using his contractor’s discount for the Douglas-fir exterior-grade plywood used for the hull planking. I don’t know how much I spent, but it was likely less than $38.

Most every weeknight after dinner and homework, I would go down into the garage and spend an hour or two working on the boat. Not much got done on the weekends—Friday was “date night.” Dad didn’t help much with the construction. Although he was a very competent woodworker, he felt that this was my project and believed I would learn more by making mistakes and figuring out how to fix them. More than once, I had the unfortunate “measure once, cut twice” experience. Once or twice each week, Dad would look over my work, and explain what I was doing right, and point out where I could do better. Occasionally, my friends would drop by to see what I was up to; they were always amazed that I would even try to build a boat.

For the previous two summers, I had worked as an apprentice carpenter in my grandfather’s construction company, so woodworking was not completely new to me, but building the boat was a real stretch of my skills. I built it on a pair of sawhorses, instead of the two A-frame supports called for, and used secondhand power tools: an old 1/4″ single-speed drill, a beat-up circular saw that Pa Kelly had given up on, and a tiny jigsaw of my dad’s. I bought a carpenter’s framing square, a decent rasp, and a block plane.

The forward ends of the plywood bottom panels required steaming to bend and twist them into place. I borrowed my new stepmom Mildred’s steam iron for this task and managed to burn it out. She and my dad had been married less than six months, and she was not impressed.

There were nearly 400 screws in the boat, all driven in by hand. The magazine article called for caulk on all the joints below the waterline, and Weldwood waterproof glue elsewhere, but my dad suggested that I should use the glue for all the joints. Weldwood Plastic Resin Glue, a urea-formaldehyde formula, is nasty stuff. It’s a brown powder that, when mixed with water, turns dark, and has the stinging, eye-watering smell of formaldehyde. Unless just the right amount of water is mixed in with the powder and the joints are gap-free and put under a lot of clamping pressure, it won’t have any strength at all. At the right consistency it’s a sticky mess and gets all over everything. The only thing that was worse was Dad’s suggestion to fiberglass the hull. He did spring for the fiberglass cloth, resin, and catalyst, but he left the messy job of sheathing the hull to me. The polyester resin in common use then was “aromatic” to put it mildly, and everything in the house soon absorbed the smell of the resin. Again, my poor new stepmom was not impressed. I knew she was irritated by the situation, but she never made a big deal out of it. She knew that the project was important to me and was always supportive. She was an exceptional person, a great stepmother, and we eventually became very close.

Courtesy of the author

Courtesy of the authorI have very few photos of my first PM-38, TERRY’S FERRY. I’d give a lot if I had a picture or two with the boat in the water, but they just don’t exist. Back then, in 1963, I didn’t have a camera, and my folks weren’t much into photography. That’s 16-year-old me at the helm. In this picture the lack of any paint on the interior is clearly evident.

Dad found a used 1959, 40-hp Elgin outboard motor in the boat department of the Sears store on Geary Street in San Francisco. Yes, our local Sears and Roebuck store did actually have a boat department. Elgin, the Sears in-house brand, was made by Scott-Atwater and would provide plenty of power. The Popular Mechanics PM-38 pictured in the magazine was powered by a 28-hp Johnson and could do 38 mph; and the boat was rated to take up to a 45-hp motor.

Courtesy of the author

Courtesy of the authorThese shots were taken in the driveway of our house, likely the day Dad and I loaded the boat onto the trailer and mounted the Elgin outboard.

It took me eight months to build the boat, working around six hours per week on it. The math says I spent somewhere around 180 to 200 hours total. I don’t think it could be built in 38 hours.

Terry McIntyre

Terry McIntyreMy stepmom and my dad were impressed by what I had built and were proud to pose with the boat.

I finished the PM-38 in April 1963. We named it TERRY’S FERRY. After school on Friday, May 3, 1963, my best high school friends—Bill and Dave —and I towed the boat with my grandfather’s F-100 pickup to Lake Berryessa, a 15-mile-long reservoir in Napa County, about 75 miles north of San Francisco. We set up a tent in the campsite at the Berryessa Marina. It rained all that night; our campsite was a muddy mess. It was chilly the next morning, but the sun came out, we launched the boat without much fanfare, and all three of us piled into the boat and motored away from the dock. The first thing that happened was the propeller shear pin failed, and I had to get into the water to replace it. (Fortunately, I always bring a tool kit the first time out.) The hull was watertight, but in a tight turn, water just poured in through the hull-to-deck joint. On top of that, the old cable-and-reel steering system was wasn’t working properly. I muttered something like, “Well, what else could go wrong?” and leaned back; the helm seat snapped loose from the bottom and I tumbled into the back of the cockpit. In spite of all the problems, we all did get water-skiing that day—I conned the boat while kneeling on a flotation cushion.

Popular Mechanics did not lie about the boat’s performance: it was indeed fun and fast. The boat would show its transom to most anything; it would flat-out fly. It was a great ski boat, hardly any wake, although a good slalom skier—like my buddy Dave—could get the boat to fishtail a little when he made a tight cut.

I finished the hull with white oil-based house paint scavenged from Pa Kelly’s scrap pile. I had varnished the deck but it was made from interior-grade mahogany plywood and deteriorated quickly. After two summers, I ’glassed the deck and repainted the whole boat with pencil-yellow marine enamel. I also replaced the original bucket seats with a back-to-back bench, upholstered with slick black Naugahyde. Big mistake—the black seats got really hot in the California summer sun!

We did not have a good experience with the Elgin outboard. About every second or third outing, something went wrong. Scott-Atwater outboards have a reputation for being great runners when they run, but they are finicky. The Elgin 40 was a two-cylinder engine with twin carburetors, and the carb floats would often stick, and then the engine would simply refuse to start. I got into the habit of picking up the trailer tongue and dropping it on the ground prior to taking the boat out—this would sometimes unstick the carb floats. In the spring of 1965, my dad and I took the boat fishing on San Francisco Bay, and on the way back to the launch ramp, the engine suddenly developed a rattle like a handful of bolts being shaken inside a coffee can. The engine got us home, but in the garage, we took it apart and found the crankshaft had broken. Fortunately, the break was oblique and inside one of the engine’s main bearings so the shaft could still deliver power to the propeller. To its credit, the engine hobbled along and got us to shore that day, but it was a goner.

Not long after the Elgin died, I passed by a small boatshop in our neighborhood and noticed a used 1960 Johnson 40-hp Sea-Horse in the front window. I went in and inquired about the price: $200. I was then a freshman engineering student, but I had a part-time job that paid $100 a month and, to my amazement, they let me purchase it on credit—$20 down and then $16 a month for 12 months. The Johnson, unlike the Elgin, was bulletproof. It powered TERRY’S FERRY for the next eight years, and two subsequent boats, until I turned it in on the purchase of an Evinrude 75-hp engine on my first “real boat”—that is, one that I didn’t build myself—in 1982.

All through a five-year courtship with Antoinette, my college girlfriend, we often took the boat water-skiing at Lake Berryessa. Summer days with a hot boat and a pretty young woman in a red and white polka-dot bikini sitting next to you—well, if that doesn’t make you a happy guy, I don’t know what will.

In late August 1965, Bill, Dave, John, and I—inseparable friends from high school—got together for a day on the lake before heading back to our separate colleges for our sophomore years. By that time, Antoinette and I had been dating for 15 months, and were starting to get pretty serious and would eventually get married. Bill brought this cute redhead he had been dating for a month—they would get married three years later. John brought Rosie, a classmate whom we all knew. Dave didn’t bring a date, but he brought beer even though we were all 19 and below the legal drinking age.

It took three trips out to a small island near the marina with the people and gear: beach chairs, a couple of ice chests, a grill, and charcoal, not to mention the skis and ropes, and towels and the like. We set up our little day-camp site near the shore under oak trees for some shade. Four people was the most the boat could seat, so we used the campsite as a base while we water-skied with just the driver and observer aboard. We got all the girls up on two skis. Dave tried to teach me to do a “beach snatch”—getting up on a single water ski from the beach without getting wet. I just couldn’t get the hang of it—I either got the tow handle pulled out of my hands or did a face plant into the water. We barbecued hamburgers and hot dogs, ate Antoinette’s chocolate chip cookies, and drank Dave’s Colorado Kool-Aid (that’s Coors beer for the uninitiated).

It was a Sunday afternoon, and we had intended to pack up and head home around 4, but we were all having such a great time that we lost track of time. Around 6:30 or 7, sunburned, tired and happy, we realized that we needed to get going. Instead of the three trips that we took to get to our campsite, we ended up with all seven of us and all the gear in the little boat heading back to the marina. I was at the helm, all the equipment was in the cockpit, the gals were sitting on the side decks with their legs inside the boat, and the guys were sitting on the front deck. Maybe the boat had 6″ of freeboard. There was no way even the Johnson 40-horse could get the PM-38 on plane, and even if it could have, it would not have been safe with the boat so terribly overloaded! It wasn’t far, mostly inside the 5 mph “no wake” zone anyway, and we made it back to shore safely. We loaded the boat on the trailer, all hugged, said our goodbyes, and promised each other we would do it again next year. But by the next August the war in Vietnam would raise its ugly head. Bill and Dave, who were in the Navy reserve, would be called up to active duty, and I was in USAF Officer Candidate School. While my buddies and I remained lifelong friends, that was the last time the four of us would be together. It was one of my best boating days, ever.

By the summer of 1971, the PM-38 had seen the last of its good days. The inexpensive materials used in construction and the lack of paint on the interior led to framework decaying, particularly around the transom. It was also starting to leak badly. Antoinette was pregnant with our first child, so the boat didn’t get used much that summer. After eight years, its time was almost up, but it had been a great little boat, worth every bit of $38, and every hour it took to build.

Courtesy of the author

Courtesy of the authorIn May of 1972, I had nearly completed ORANGE CRATE– a Glen-L Rebel that was the PM-38’s replacement. My college lab partner, Ron, and I moved the PM-38 hull from my trailer onto his new trailer, and the Rebel off its building form and onto my trailer. Then we mounted my “bulletproof” Johnson 40 hp Sea-Horse on the transom of the new boat. Right after this, Ron and I took out a circular saw and cut the back end off the PM-38 hull. I don’t recall that Ron ever renamed the boat. The car in the garage is my 1956 Chevrolet Bel Air sports coupe. It was my car during my undergraduate college years, and I used it to tow TERRY’S FERRY for most of the boat’s life. After it cracked a piston, I had every intention of tearing down the engine, but life got in the way. When we moved to San Jose in ’73 I sold the car, not running. Big mistake—that car would be worth big bucks today!

Over the winter of 1971–72, I built another, bigger, ski boat—a Glen-L Rebel—to replace the PM-38. When the Rebel was near completion, I asked a college friend to help me put the new boat on the trailer, mount the engine, and take the old PM-38 to the landfill. Ron agreed to help, but then asked if he could have the boat instead of dumping it. “Sure,” I said. He bought a trailer and engine (a 40-hp Merc) and we used a circular saw to cut the back 6” off the boat to get rid of the worst of the rot. We fabricated and installed a new transom and put a new layer of fiberglass tape and resin on all the seams. Ron used the boat for another three summers. The last time he used the boat he was running it at speed when the joint between the front and rear bottom panels failed, and half the bottom peeled off. The boat sank like a stone. Ron and his wife were both wearing life jackets and were quickly picked up by a passing boat, and everyone was okay. As far as I know, my PM-38 is still at the bottom of Lake Mendocino.

A half century and several other boats have passed since the good times with my PM-38. I follow a couple of wooden-boat and boatbuilding pages on Facebook, and one day the original 1962 Popular Mechanics article popped up along with a story about someone building a PM-38. It brought back all these great memories. Today, Antoinette and I have a genuinely nice 27′ express cruiser that we motor frequently on San Francisco Bay—and I need another boat like a hole in the head—but the post about the PM-38 got my attention. I didn’t intend to build it, but the retired mechanical engineer in me got thinking about what I would do differently if I did. My original intent was to maybe build a 1/12 scale model.

Alan Scott, the designer of the PM-38, had gone all-out to minimize the hull weight, as the 1962 article put it: “Since everyone knows that weight is one of the most important performance factors, our designer laid out plans for a fast planing hull and then hacked off weight wherever possible.” In doing so, I think he built in some structural weaknesses. The original design does not have a true sheer clamp: the deck and sides are joined on a 3/4″-square sheer rail screwed to the outside of the hull. That seam nearly always leaked, and frequently popped loose. Likewise, the spacing between the rearmost frame and the transom was nearly 4′, and the side decks became a little spongy over that span. Outboards have also changed, and a 20″ shaft is now the standard, rather than the 15″ shafts they had back then.

The possibilities for improvements became my checklist. I started with sketches and then some scale drawings. When I got to the point of lofting some full-sized patterns for the frames and other components on heavy paper, Antoinette said something like, “Go ahead and build it, you know you will be unhappy if you don’t, and you want to take the grandkids skiing, don’t you? Just make sure that my car will be in the garage every night when you are building it!”

I got serious about designing. To make the sheer-to-deck joint more robust, I added a breasthook, deepened the hull by 3″ to accommodate a 20″-shaft outboard, and notched the top of the frames for a 1-1/2″-square sheer clamp. To bridge the gap between the transom and the original rearmost frame, I drew in an additional frame 18″ forward of the transom and tied it into the transom knee. With the deeper hull it was possible to add a self-bailing motorwell, and I added a drain plug in the transom. After a day of water-skiing in the original, we would have to use a bucket and sponge to get all the water out of the bilge. I’ve gotten too old for that.

Terry McIntyre

Terry McIntyreIn March 2020 the boat was just about ready to plank. Here you can see many differences between my new version and the original—the framework was assembled on a stout building form on casters instead of scrap lumber A-frames, and the sheer rail and breasthook have been installed. The rear partial frame that I added is tough to see, but it’s there, connected to the transom knee.

These modifications only moderately increased the weight of the hull (from about 200 to perhaps 225 lbs) but made it far more structurally sound. The beam increased by almost 6″ and the length by 3″. When I ran these numbers through the formulas in the U.S. Coast Guard “Safety Standards for Backyard Boat Builders” I was pleasantly surprised to find that these seemingly minor changes would increase the recommended maximum load by nearly 500 lbs, and the maximum engine size from 45 to 60 hp.

I started construction in the fall of 2019. To meet Antoinette’s requirement that her car be safe in the garage at night, I built a stout, wooden construction frame on casters, so that I could roll the project outside and cover it with a tarp when I was not working on it. The boat turned out to be my COVID-19 “sanity project” during the lockdown.

I’m no longer a kid on an allowance, and money is not the issue it was for me in 1962; I used much better materials this time around. The framing is all kiln-dried clear straight-grained Douglas-fir, and the planking is BS1088 meranti marine plywood. Wood is still wood, but adhesives have greatly improved in 60 years. The entire boat was assembled with marine epoxy, with the screws all removed after the adhesive had set, since the epoxy alone provides the needed strength. The hull exterior is covered with fiberglass, and the entire interior is encapsulated in epoxy, to ensure that the wood remains dry and avoids the rot problems encountered in the original. This boat will likely outlive me.

My plan was to make the hull white with a mahogany deck, like the 1962 version, but when I got the hull planked, Antoinette looked at the meranti ply and said, “You aren’t going to paint that gorgeous wood, are you?” It was a lot more work preparing so much of the plywood to be finished bright. The results just scream the 1960s. The crowning touch would be a wraparound windshield similar to one from a ’57 Chevy—but I have not yet been able to find one.

Antoinette found some nice back-to-back pontoon-boat bucket seats online. I had to shorten them a bit, but they are serviceable and the brown and tan complement the hull’s finish. I also added floorboards to the interior, topped with faux-teak-decking carpet. The boat has running lights and full instrumentation, making it more complete (and legal) than the original.

Terry McIntyre

Terry McIntyreTERRY’S FERRY did have a bow light on the front deck. I have no idea where it came from—I must have salvaged it from somewhere—it never was connected to a power source. A speedometer or tachometer would have cost far more than I could afford. In the second PM-38, I installed the tachometer and engine monitoring that came with the new Evinrude, a trim gage, and pitot-tube speedometer. Switches for the running and anchor lights are to the right of the wheel. The steering is a modern no-feedback rack-and-pinion system instead of the cable-reel-and-pulley type I used in the 1960s. The handrail on the dash makes it much easier for a passenger in the front seat to hang on in a turn.

The cost for the hull materials, not including the hardware, seats, and steering, came to about $900, which was substantially more than I spent on the original. I took the article’s Materials List from the original PM-38 and priced the lumber, plywood, fastenings, and adhesives on a home improvement store’s website to see what they would cost today. An inflation calculator says $338. The big-box store materials came to $450. I spent about 300 hours building the new PM-38, about 100 more than the first one. Most of the increase over the original was in the work to prepare the hull and interior for a bright finish: eight coats of spar varnish, wet-sanded to 2,000-grit. It was far from a 38-hour build but worth the effort

I was initially undecided about how to power the boat. A period engine would carry the vintage look from stem to stern, but in the end, I decided that I’m too old to fight with a temperamental 60-year-old motor, and new engines are far more ecofriendly. I found a new 40-hp Evinrude E-tec which fit the new motorwell and promised plenty of power. It weighs nearly 250 lbs, over 100 lbs more than my 1960 Johnson. The original engine had a rope-pull start, and the new one has an electric start that requires having a 50-lb battery aboard.

We launched the boat for the first time in late April 2021. I considered towing the boat to the ramp with my classic ’69 Chevrolet Camaro, the car I bought new as my college graduation present to myself and used to tow my first PM-38 50 years ago, but decided on towing with my more powerful and less precious Chevy 4WD pickup. We poured some champagne on the bow and christened her RETRO-ROCKET. At the dock, the additional 200 lbs of weight of the engine and battery made the transom sit a little lower in the water than I would have liked. I was very glad I had added depth to the hull and its load-carrying capacity.

Terry McIntyre

Terry McIntyreWhen I got my undergrad engineering degree, I treated myself to a brand-new 1969 Chevrolet Camaro. I put a trailer hitch on the Camaro, and it became my tow vehicle for the summers of ’69, ’70, and ’71. I’ve kept the Camaro stock and original, and it still looks and runs great. I couldn’t resist hooking up the new boat to the Camaro and driving it around the block.

There were several folks on the launch ramp, and they immediately started commenting on how nice the boat looked and asking what it was. “That’s a cool old boat, what year is it?” has been the most common question.

Terry McIntyre

Terry McIntyreTied up to the dock, the new PM-38 is overboard for the first time. Whenever we have it at the dock, it gets lots of attention. The accent stripe down the middle of the deck is unstained mahogany—I had to put the stripe in, because I wasn’t happy with the panel joints on the deck. I milled out the strip with my router and added the new piece. I was pleased with the result.

With just me aboard, the Evinrude brought the boat on plane nicely, but as the speed approached 30 mph it started to porpoise badly. I returned to the launch ramp and had Antoinette step aboard. While the porpoising was noticeably reduced with her aboard, I was not comfortable in pushing the boat any harder, and we called an end to the first sea trial.

Terry McIntyre

Terry McIntyreI was shocked by how fast the boat is. Here, Antoinette and I are running flat out with the speedometer showing 46 mph. The USCG allowable power calculation shows that the boat would be approved with a 60-hp outboard. I can’t imagine how fast it would be with that power.

On the web I discovered that porpoising is a common problem with late-’50s and early-’60s boats repowered by modern outboards. I moved the battery forward to under the front deck, and added a set of automatic trim tabs; the combination both eliminated the porpoising problem and improved the at-rest trim. Like the original, the new PM-38 “runs like a racer’s dream,” just as the Popular Mechanics article had promised. The boat is scary-fast— with just Antoinette and me in the boat, the pitot-tube speedometer indicated 46 mph flat out! With four adults on board, she hit 40. At speed, with the engine trimmed out, the boat throws a spectacular “rooster tail.” I haven’t tried to pull up an adult water-skier yet, but my teenaged grandkids get popped right up!

Terry McIntyre

Terry McIntyreMy grandchildren were the raison d’être for the new PM-38. Here are three of my four grandkids with Moira, the eldest at the helm. Josh, to port in the back, was the most excited of the bunch, and was the first one we got up on skis.

Marion Speed

Marion Speed The engine is trimmed way out, raising the bow, and we are about to do a screaming 180-degree turn with an impressive rooster tail while three mid-septuagenarian “kids” relive a day from a long time ago

For our first real outing with the boat, we met with a group of old high school and college friends (including four of the seven who were there on that day back in 1965), for a day on the water in the California Delta. Racing along in the reincarnation of the PM-38 was a fabulous experience. For most of that day, I was 19 again. Not all the tears in my eyes were from the wind.![]()

Terry and Antoinette McIntyre live in the small town of Morgan Hill, California, 75 miles south of San Francisco. They have been married for 52 years and have two grown children and four teenaged grandchildren. Terry holds mechanical engineering degrees from San Francisco State University, the University of California and Stanford University, and is a licensed professional engineer in California. He retired from General Electric Power Systems in 2002 after a 33-year career as a research and development engineer and project manager, designing and building nuclear power plants. He has been a boater since 1960 when his father got involved with a group of co-workers who were boaters and waterskiing enthusiasts. Terry has owned seven boats over the past 60 years, four of which were homemade wooden boats. Terry and Antoinette boat primarily on San Francisco Bay in their 27′ power express cruiser, and are looking forward to using the new PM-38 runabout in the California Delta.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

What a great story and so much fun! You made all the right choices in doing your redesign of the original. I have seldom seen so much utility in a 14 foot motorboat. Really nice job to involve your grandkids and Delta sports.

What a fantastic story. Once again I got caught up in the excellent writing and read from start to finish. My teenage dream of becoming an Engineer was squelched by my high-school policy of males only in the drafting classes. I’m now 91 years and have precious memories of the four years I was the Assistant to the VP of Engineering in a food processing machine manufacturing plant. I had the privilege of overseeing 19 Engineers and draftsmen and writing the Service Manuals for the machines. Never an Engineer, but always a thinker and tinkerer. Congratulations Terry on the publication and recreation of your dream boat!

Wow, this takes me back to those heady days of the sixties, reading Popular Mechanics and dreaming of building boats. What a great story!!!

Wonderful story!

Having been the owner of a rowing pram at age 11, the itch of having a boat again has always stayed in me. Last year’s lockdown was the perfect excuse to start building a Wee Lassie canoe that has performed wonderfully, but the itching doesn’t end. Maybe I need a new project? Thanks for sharing your story, so engaging and well written. Nostalgia is a good motivation.

Terry,

What a fabulous story. A brief glance brought me into a complete read. I noticed that you retired from the GE nuclear division. I am sure that you must have crossed paths with my father in law, Jack Williams. He was in the same division I suspect and stationed in your part of the world.

Boating is always in my blood. Helps to have an understanding wife who shares the experience. I should have been more discerning before I married. Anyhow, great story and great writing, Terry. Looking over some plans by Sam Devlin now.

Fantastic story! I grew up with a PM 38 in the family that my father built in ’63. Painted plywood, ‘glassed bottom and varnished interior, similar plastic wraparound windshield. Even our Tee Nee trailer looked similar to the one in your picture. Its first motor was also an Elgin and was ultimately replaced with ’64 Evinrude 28 HP Speeditwin. We all learned to waterski behind it, my dad included. That boat had a marvellous sliiiiiiiiiide/swish through turns at speed! The substantial flare of the hull sides certainly kept it from tripping on its chines. I don’t remember porpoising ever being an issue but it was prone to pounding hard on a choppy lake and large boat wakes could be quite the experience! Ultimately the family outgrew the boat and in 1974 it was replaced by a 67 Starcraft Jupiter that I still use today. I have many photos and the original magazine my dad built the PM 38 from and harbour thoughts of building one myself one day. It would be logical next step up from the Bolger row boat I did with my kids years ago. Funny enough I too am retired engineer…..I may have to connect somehow as your modernization certainly sounds like the way to go. Thanks for sharing your story and putting a smile on my face.

That was a beautiful article… my favorite ever

Wow, what memories you have unearthed for me! I too built a PM-38 in 1964 in our walk-out basement in upstate New York. I was 17 that spring and had no woodworking experience but followed the instructions to the letter. My Dad sprang for a 33 Johnson and wrap-around windshield.

The boat got its biggest test on Kipawa Lake in southwestern Quebec. It survived that and lasted quite a few years. Dad loved scooting along flat out. There’s a picture of that somewhere.

Thanks for the article and the link to happy times.