My penchant for Scandinavian boatbuilding techniques once prompted Matt Murphy at WoodenBoat to tell me that it seemed as though I was trying to “get in touch with my inner Viking.” But when I look around, I see that I am hardly alone. Some aesthetics—think of Japanese architecture, Italian stonework, New England barns—have universal appeal and compel respect, and the double-ended Norse boats are in that world-class league. The fact that thousand-year-old workboat designs are widely influential even for modern plywood glued-lapstrake small craft is a marvel to me. One of the very encouraging trends in this direction is that a company specializing in the production of kit boats—most of them kayaks—has turned to Scandinavia for inspiration, too.

The boat I’m thinking of is the Skerry design by John Harris at Chesapeake Light Craft. Like other companies offering prefabricated kits for lightly planked plywood boats, CLC got its start in another great boat inspired by antiquity—the kayak. The widespread success of kayaks is no surprise—no other boat gets more use, since they’re so easily transported on a cartop and can be quickly launched in a wide variety of settings. Fifteen minutes after getting home from work, you can be on the water. But even for diehard kayakers, there’s a certain appeal in having the ability to sit up in a boat and move around a bit or to carry another person and some gear that needs to be easily accessible during the trek. And, why not let the wind do the work sometimes?

Photo by Corinne Ricciardi

Photo by Corinne RicciardiA simple rig and a pleasing hull shape inspired by Scandinavian types make the Chesapeake Light Craft Skerry an easy daysailer to take out for coastal explorations.

A lightweight 15′ double-ender, the Skerry fits the bill admirably for those who want such a craft but may not be confident in complex traditional construction. Builders with experience or confidence can work from plans to turn raw 6mm and 9mm plywood sheets into a boat. Others will choose to work from a CLC kit. Almost everything in the Skerry kit—exceptions being the rubrails and mast—is made of plywood shapes precut to fit neatly together in what CLC calls the LapStitch method, their variation on stitch-and-glue construction.

The result will be a boat that strikes a balance, as any boat must. This balance is between performance under sail and under oars. An excellent pulling boat rarely makes a great sailer, and a boat tricked out with sailing as its primary function rarely rows very well. The Skerry doesn’t go too far toward either extreme.

Photo by Corinne Ricciardi

Photo by Corinne RicciardiIntersecting curves and planes of plywood, well filleted with epoxy, give the Skerry strength and stiffness and also provide built-in flotation forward and aft.

She has two rowing stations, so that the right fore-and-aft trim can be struck with the selection of a rowing station. With a passenger aft, the boat will behave just fine if the oarsman takes the forward rowing station. To use that thwart, however, the mast will have to be shipped. For a solo outing, the hull will balance best while rowing from the center thwart, and in that case the mast can remain stepped where it is. In light air, the boom and sprit can be pushed up to vertical, bundled with the mast, and wrapped a few times and then knotted with the sheet to get everything out of the way. In much of a breeze, it will be best to get it all down and tucked away in the boat.

In many traditional Scandinavian boat plans, the sails generally look small, and the Skerry’s spritsail follows suit. Like her forebears, she has a sail that is suitable for general conditions and is simple to use and inexpensive to install. Sail arrangements can look a bit deceptive in two-dimensional plans. The rig can look odd in the sail plan, but the sail looks better on the boat than it does in the drawings. For those who take their practicality with a liberal serving of aesthetics, CLC offers a gunter sloop option.

The Skerry sail is set quite high up the mast by design, leaving room to row even with the sail up. It’s a little too high for my eye, and I think it could come down substantially with no harm; I’d be inclined to install a brailing line (to help haul everything to vertical) to get the rig out of the way when rowing. One great advantage in flying the sail high, though, is that it offers really good visibility forward and on all sides on all points of sail. When you look at the sail plan, the sail can look too small, too, but it is big enough to drive this hull, and in much of a blow you wouldn’t want anything any bigger. There are no reefpoints on the sail, but one depowering method is to “scandalize,” or take the sprit right off and let the peak fall, making, in effect, a triangular sail. If it’s still too much power, it’s time to get the rig down.

Photo by Corinne Ricciardi

Photo by Corinne RicciardiThe daggerboard, tensioned with a shock cord to keep it down, is essential when sailing, but it has to be removed when rowing—and the slot plugged to avoid a wet seat. Disconnecting the very simple mainsheet leaves nothing in the way on the thwart when switching to rowing.

The Skerry’s rig is meant to be simple, and it is. There are only three lines to handle: a downhaul, a snotter, and a sheet. On the boat I sailed, the boom was fixed to the mast by a simple gooseneck. For the sprit—that wooden pole running diagonally from the mast up to the highest point, or peak, of the sail—CLC uses a simple dowel set crosswise through the sprit to form a cleat onto which a line from the peak of the sail can be made off. A similar dowel-cleat is fitted at the heel. The heel receives the “snotter,” the traditional term for a line that, in addition to providing no end of linguistic amusement, performs the critically important task of controlling the sprit’s tension. The sprit heel is slung in the snotter, which is hauled to increase tension or eased to decrease it. The downhaul provides a rudimentary way to increase or decrease luff tension a bit—sort of like a cunningham line. The sheet, of course, controls sail trim.

Anyone sailing a new Skerry for even a short length of time will probably very soon start looking for ways to improve the rig. This is one of the joys of any boat, whether built from a kit or otherwise—finding ways to take ownership of it, to make it suit your own ways. I would probably try to find some way to loosely cleat the sheet, for example—something that would allow very quick release. A cam swivel base of the type used by racing dinghies might work, as would a fairlead and a cam cleat set on the aft edge of the thwart, providing that the part of the line leading to the helmsman’s hand comes from the lower block—and remembering that the oarsman will have to work around the gear. Even a simple belaying pin might work, too—just enough to take a turn (but never belaying, and never letting your hand off the sheet) so you can give your arm some help on long, easy tacks. A pin could be easily removed when rowing. If I chose any such method, I’d strengthen the thwart where the sheet comes aboard.

Photo by Corinne Ricciardi

Photo by Corinne RicciardiA small sprit rig is simple and fun to sail, with only three lines to tend: the sheet, which controls the sail trim; the snotter, which controls the tension on the sprit and therefore the relative fullness of the sail; and the downhaul, which tightens or loosens the leading edge.

If I spent most of my time solo-sailing, I would also find a way to lead the snotter—and probably the down-haul, too—aft to be within easy reach of the helmsman. The snotter, especially, is a line that demands fairly constant adjustment. Hard on the wind, it needs a lot of tension, and unless you’re willing to tolerate saggy-looking sails, it will need to be tightened with some regularity. Downwind, it will need to be eased to let the sail find its best shape. In either case, the adjustment involves a line made off to a cleat near the base of the mast. Unless you’ve got crew, you’ll have to leave the tiller to go forward to the mast to make these adjustments—or, more likely, just live with the sail shape as it is. The ability to make such adjustments without leaving the helm would greatly add to the enjoyment of solo-sailing the boat.

Ah, yes, about that tiller…. The tiller-and-yoke system, which this boat uses, is traditional to some kinds of Norse double-enders, and it’s commonly used in, for example, the Caledonia yawl and other Scandinavian-inspired boats with which Iain Oughtred has found such widespread design success. It can take some getting used to, but that is quickly accomplished. Its greatest advantage is in allowing the helmsman to find the right place for his weight, both athwartships and fore-and-aft, especially when solo-sailing and even more especially in light air. This is particularly important in a double-ender. Instead of a traditional tiller forcing you to sit one side or the other—which may put too much weight outboard in light air—you can move to the athwartships point where the boat likes it best for any given force of wind or point of sail. Steering with the yoke is simple, rather like walking arm-in-arm.

Photo by Corinne Ricciardi

Photo by Corinne RicciardiThe yoke tiller can seem awkward at first, but it becomes second nature after a little while.

I’d find some way to keep the tiller aboard, though. If you’re going forward to deal with that snotter, or if you’re shoving off stern-first from a beach, the tiller has a nasty habit of going overboard, and it can easily get fouled. A light line with a slippery knot loosely looped around the tiller could keep it inboard in such circumstances.

At 90 lbs, the Skerry is in the cartoppable range. Depending on the car, it could be a pretty high and awkward hoist for two people, and the rack will have to be a sturdy one. I’d much rather choose a light trailer, which would provide a great deal more freedom, especially for solo-sailing.

Harris says that by summer 2007 his company had sold about 300 Skerry kits. It’s easy to see why. It’s a pretty hull. It’s a pleasure to look especially at the curve of the stern, which I think is just right. There’s an old saying, which I’m told is of Scandinavian origin: “Line for duty; curve for beauty.” There’s a reason why I’m not alone in admiring these curves and hull forms, which are distinctly well suited to glued-lapstrake plywood construction. They look at home on the water because they are.

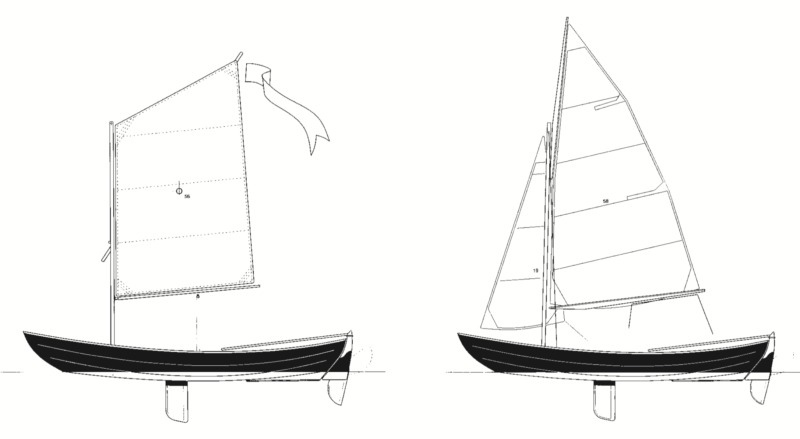

The original CLC Skerry rig, left, shows a fairly small sail set rather high on the mast. Its advantages are excellent visibility, only one sheet to tend in tacking, and plenty of headroom. For a more rakish-looking sailing rig, more sail area, two sheets to handle, and better windward performance—but at greater expense and a loss of simplicity—an alternative sliding gunter sloop rig, right, is available.

Skerry plans, kits, and completed boats are available from Chesapeake Light Craft.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

It is a pretty hull, but to me the sail plans leave much to be desired. I’d like to see it with a small dipping lug – a lot prettier. You’d need to move the partner aft a bit, but it might be a fun rig to handle and perhaps not too hard to manage if one kept it small enough.

Without depth of analysis, I’m inclined to think the 15′ Skerry of 57 sq ft sail area would’ve improved by incorporating the 13.5′ Lighthouse Tender Peapod‘s rig of 95 square ft. The Skerry is a great boat but the Skerry’s daggerboard might be improved with the LHT’s centerboard.

Having built a Jimmy Steel peapod at WoodenBoat School, I’m partial to the Tender’s peapod heritage. A Tender vs a Skerry with the Tender’s sail might cause a good deal of back-and-forth consideration, but either would be a great choice.

I built the balanced lug version of the Skerry in 2017 and have sailed about 100 hours on the boat so far, all solo. I lead the downhaul down through a small hole in the port side of the front deck to a block, from there to a cleat between the middle and aft thwart on the port gunwale. Same with the halyard, led to a cleat on the starboard gunwale. That way I rarely have to go forward of the middle thwart. I’ve been able to row, leaving the daggerboard in place; you just have to scoot forward a bit. To sail, I sit on the floor of the boat, facing forward, atop a cushioned mat, and lean back against a pillow lying against the front edge of the aft deck. The tiller is usually resting atop my right shoulder. Depending on the winds, I use extra ballast, in the form 10-lb to 15-lb dumbbells, placed in little compartments I’d built under the middle thwart and forward from there up to the mast step. Others I’ve seen use water bags. The Skerry is fast, both rowing and sailing. I use 8 1/2′ wooden oars and the rowing is pleasurable and worthwhile – as in, for the effort put in, you really do cover a lot of ground, fast. My set-up time, from time of arrival at boat ramp with boat on trailer, to put-in, is about 35 minutes, as long as I don’t dillydally. I use a typed checklist to be sure I’ve got everything, and a second checklist for launching. A lot of little steps. All much worthwhile for a day spent on the water with a boat you’ve built that’s a sight to see and a pleasure to sail & row.

The beauty of this particular design by John Harris is the versatility it offers. I’ve had a balanced-lug Skerry since 2015.

It has been sailed and rowed extensively in the Pacific Northwest, in fresh, salt, and some “interesting” weather conditions. It’s been trailered and car-topped. Self-rescued from a capsize. It was double rowed and portaged on the Bowron canoe circuit. Towed as a tender through the San Juan’s.

There are many small boat designs that would out perform the Skerry at one or two of these tasks. The Skerry has proven to be fast and trustworthy through all of them. It has handled everything I’ve thrown at it with style and grace.

I became the proud owner of a skerry a couple of weeks ago. Imagine my delight in seeing it highlighted in this month’s Small Boats newsletter!

I haven’t been out in it many times yet but I’m already delighted with my new little vessel here in the waters of Casco Bay. The balanced lug (not pictured in the article) has been delightfully, refreshingly simple to sail and does well in light air.

There’s no denying her “plywoodyness” but she’s still a smile factory.

Cheers