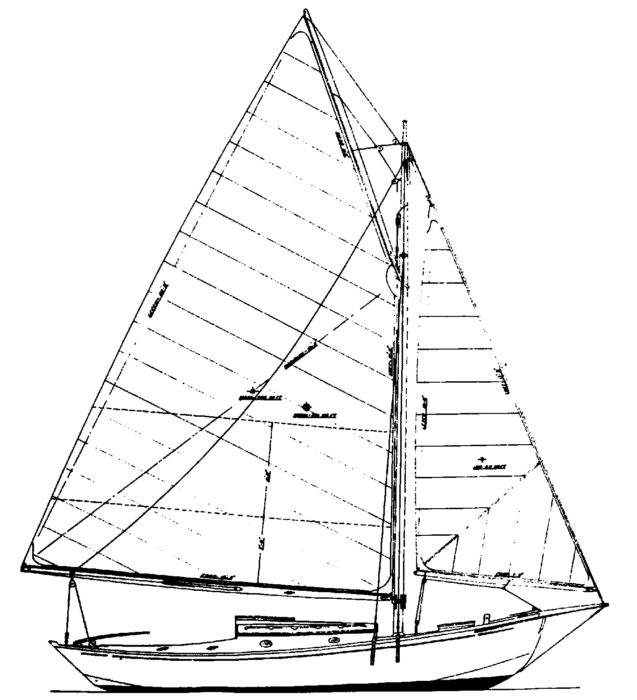

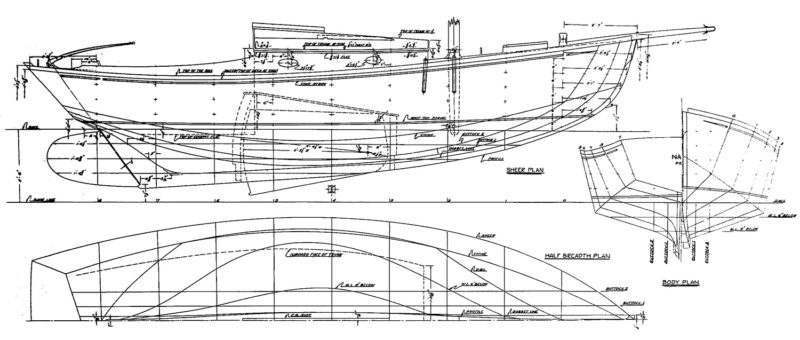

FAIREHOPE is a 21′ gaff-rigged sloop designed by Nelson Zimmer. In my correspondence with him during the time FAIREHOPE was being built, he wrote, “I designed the little shallop in 1946 for a man in Auckland, New Zealand, as a stout coastwise cruiser.” The design was featured in The Rudder, National Fisherman, and, finally, in the design section of WoodenBoat No. 58, with a commentary by Joel White, which is where I first saw her.

Being boatless at the time and eager to have another boat, as well as the experience of building one, I was immediately taken with her straightforward and strong look, which harked back to less complicated and saner times. The very favorable comments of Joel White completed the process of convincing me. Accordingly, I purchased a set of plans from The WoodenBoat Store and began my quarter-century relationship with FAIREHOPE.

I cannot say that the construction was without significant effort, but it was relatively simple work. The hard-chined sections and sawn frames eliminated the necessity of a steambox. After two-and-a-half years of mostly weekend work, with paid help from an experienced boatbuilder friend and six months of paid weekly assistance from another friend, she was launched in June 1985.

In keeping with her designer’s intent, she is stoutly built with locally sourced live oak for the keel and backbone, and natural live oak crooks for the quarter knees and breasthook. Her design also includes a full set of lodging and hanging knees, which I laminated from mahogany. FAIREHOPE is planked with 7⁄8″-thick juniper, with a 1-3⁄8″-thick mahogany sheerstrake for additional strength. Her topsides construction is batten-seam, using mahogany battens that cover the inside of the planking seams, and copper rivets for fastenings. We also installed 1⁄4″-thick pine ceiling planking, leaving 1⁄4″ between the strakes for ventilation. Instead of caulking the topsides, we epoxied juniper splines between the planks, creating a smooth and stable surface for painting. Below the chine, she is fastened with silicon-bronze screws and caulked traditionally. The decking is plywood covered with Dynel set in epoxy, with a teak overlay for a traditional look.

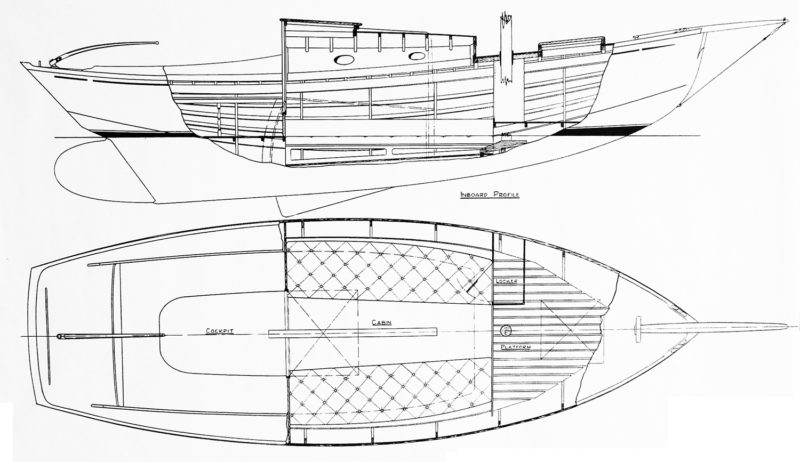

With Zimmer’s blessing, we changed the design by replacing the deep cockpit with a bridge deck and a self-draining footwell. In addition to improving seaworthiness in the event of taking a wave over the stern, this configuration allowed us to tuck a two-cylinder diesel engine under the deck. The Beta 14 engine, which is offset to port so as not to weaken the keel and dead-wood, has functioned quite well. I am presently using a two-bladed folding prop to reduce drag. Maximum speed under power is 61⁄2 knots with an easy cruising speed of 51⁄2 knots. Another change was the construction of a small bulwark to replace the toerail, raising the sheer height enough to allow us to clandestinely raise the cabin height to allow greater sitting headroom below while respecting the pleasing as-drawn profile.

In addition to the engine weight to port, which is offset by placing her two batteries to starboard, we added about 600 lbs of cast-lead ingots as inside ballast. Although she performed well and was relatively stiff with this ballasting, I eventually removed about 500 lbs of the inside ballast and instead gave the keel a 4″-thick, cast-lead shoe, which was bolted through the floor timbers and centerboard trunk bed logs. This placed most of the ballast as low as possible, but I retained 100 lbs of ingots for use as trim ballast. By blind luck, FAIREHOPE retained her wonderful motion and became noticeably stiffer.

D. Turner Matthews

D. Turner MatthewsThin ceiling planking, spaced for hull ventilation, gives FAIREHOPE a simple, spare appearance down below, and her accommodations permit one or two people to cruise comfortably enough.

Although FAIREHOPE is only 21′ on deck, with a 2′ bowsprit and waterline length of 16′, she sails and feels like a much larger boat. Her motion is steady and solid, with no whip-like reactions in gusts, or bouncy motion such as you might experience in some 20′ fiberglass or plywood counterparts. Rather, FAIREHOPE, in gusts, just buries her shoulder a little more and increases her forward motion proportionate to the increase in wind velocity, continuing to rise and fall to the waves with a steady and predictable motion, easing her rail slowly upward when the gust ceases.

I frequently liken her to the 1955 Buick Super we had when I was a youth. As with the Buick, which gave a smooth, solid, and secure ride, you need to pay attention to the helm, particularly in windy conditions. Also, as with the Buick, FAIREHOPE has none of the stability safety features with which modern cars are fitted to keep incompetent drivers out of trouble—rather, you must rely upon your own skills. Unlike modern fin-keel boats, for example, she will not round up if overpowered by a gust. She depends upon her helmsman to point her in a safe direction and ease her mainsheet in stiff winds, and if you do not direct her otherwise, she will continue to bury her shoulder ever deeper and hold her course to the end.

That having been said, in general, her sailing qualities are impeccable. She will heave-to if necessary; seldom, if ever, misses stays; and is relatively fast given her 16′ waterline length. Being gaff-rigged, she is not particularly close-winded, but if properly trimmed will sail herself to windward, allowing me to leave the helm unattended for brief periods if necessary.

D. Turner Matthews

D. Turner MatthewsA great advantage to the 21-footer’s design is that it can be hauled out by trailer, which not only makes maintenance by the owner practical but also allows her to be taken easily to find new and even far-off cruising grounds to explore.

I originally had one moderate and one very deep reef in the main. A friend and I once took her out in storm conditions (gusting to more than 40 mph) to see what she would do. With the second reef in the main and the working jib, we managed to stay in control for the time we were out. On another occasion on the Gulf Coast Intracoastal Waterway between Venice and Boca Grande, Florida, I averaged 4 knots solely under the working jib. On that occasion, I was comforted by the running backstays, as it was a very broad reach in about 30 knots of wind.

I now have a set of Dabbler sails, with both reefs much shallower, making their use more practical in reasonably normal conditions. In a significant test, before a Mid-Atlantic Small Craft Festival in St. Michaels, Maryland, a friend and I did a double-reefed, 8-mile beat into 20 knots of wind, with higher gusts, down the Miles River to reach the pre-festival camp-out on the Wye River (see page 18). Although it was a very wet ride, we had sufficient sail area to maintain our momentum through the very steep chop, whereas with the other sails I would either have been overpowered with one reef, or too underpowered with the second reef to keep way on into the waves.

D. Turner Matthews

D. Turner MatthewsNelson Zimmer designed his 21’ gaff-headed sloop to be comparatively simple and inexpensive to build.

For the most part, I have used FAIREHOPE for the role for which she was designed. Her simple but adequate accommodations allow for one or two people to camp-cruise in comfort. I have made numerous cruises along the Gulf Coast of Florida both alone and with various friends. I also do a lot of daysailing in the Manatee River and lower Tampa Bay.

FAIREHOPE is at her best in 10 to 15 knots of wind without any reefs, or in 15 to 20 knots with one or two reefs. I usually sail with the full main and working jib, which is club-footed and therefore self-tending. Tacking, then, is effortless, requiring me only to put the helm down and move to the high side. In light winds of 5 to 10 knots, I use a 120-percent genoa, which I had made several years ago, and with this, she maintains a reasonable speed. It does, of course, require retrimming with each tack, and with changing wind directions. With no winches aboard, however, handling the genoa requires significant effort when the wind gets much above 10 knots. As for the main, I rigged it with a classic double-ended mainsheet. With all this leverage, trimming the mainsail has never been a problem.

One of the great advantages of a deadrise centerboard boat, depending on her size, is the ability to launch and retrieve it from a trailer. During the summer hurricane season, I now pull FAIREHOPE out of the water onto her trailer, and using our local yacht club hoist, pull the mast, which stores easily aboard the boat. This also has allowed me to trailer her to faraway places, not only to St. Michaels, Maryland, but as far away as Southwest Harbor, Maine, for the 1994 WoodenBoat Show. The sailing out to the Atlantic through all the wonderful boats in Southwest Harbor remains one of the highlights of my time with FAIREHOPE.

When you sum up all of the good qualities I have mentioned, which have been learned and refined over a 27-year period, you are left with what I consider a timeless classic, regardless of when it was or will be built. I can truly say that for someone seeking a traditional, shoal-draft, small coastal cruiser to build or own, I can think of none better.![]()

Full plans (and also study plans) for the 21’ Zimmer gaff sloop are available through The WoodenBoat Store.

Designed in 1946, the Zimmer 21’ sloop’s shallow draft—only 2’ with the centerboard up—promises easy access to shoal waters for island exploration and camp-cruising. Her accommodations are somewhat spartan, but adequate for the purpose, and her ample cockpit makes cruising under sail a pleasure.

Zimmer 21′ Gaff Sloop Particulars: LOA 21’1 1/2″, LWL 16′, Beam 7’2″, Draft (board up) 2′, (board down) 4’3″, Displacement 3110 lbs, Sail area 261 sq ft

“…requiring me only to put the helm down and move to the high side…” — what about the running backstays you mentioned earlier? Having to slack off on the new leeward side and quickly haul in on the new windward side, when tacking, is what the term “running backstays” means to me. My only experience with running backstays was crewing on S-boats, and the danger of failing to tighten the windward backstay in a timely manner (i.e., potential dismasting) was something I remember being mentioned. But those boats have a tall marconi rig; I suppose there’s less risk of that with a gaff rig.